By Gëzim Kabashi

Part One

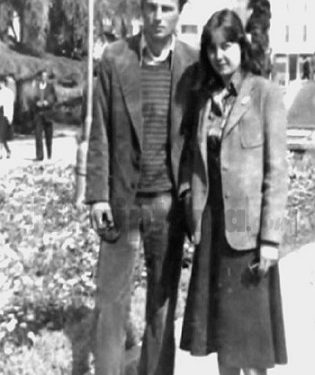

Memorie.al / Nikolla Velço will never forget the third weekend of December 1981. He was 26 years old, a recent graduate of the High Institute of Arts as a cellist, and on Sunday, December 20, he was to become a groom. He was marrying a fellow citizen from a much respected family, to whom he had been connected since she was a teenager. Tall and handsome, with a calm presence, Niko – as his friends called him – must have been in the dreams of many girls from Durrës and even Tirana, especially after an event that put the Velço family at the center of attention in Durrës, the city where they lived. The family’s youngest daughter, Marjeta Velço, not yet 15, had become the bride of Bashkim Shehu, the youngest offspring of the then-Prime Minister of Albania – the man considered the natural successor to the dictator Enver Hoxha.

With a driver for a father and a seamstress for a mother, the Velço family seemed to have been struck by a great fortune from the sky. But the five years from 1976, when Marjeta entered the nation’s “House Number 2” as a fiancée, passed with dizzying speed. And Nikolla, despite being a student, had understood many things that were going wrong. Later, he would suffer many more, simply for being the brother of an “enemy” woman.

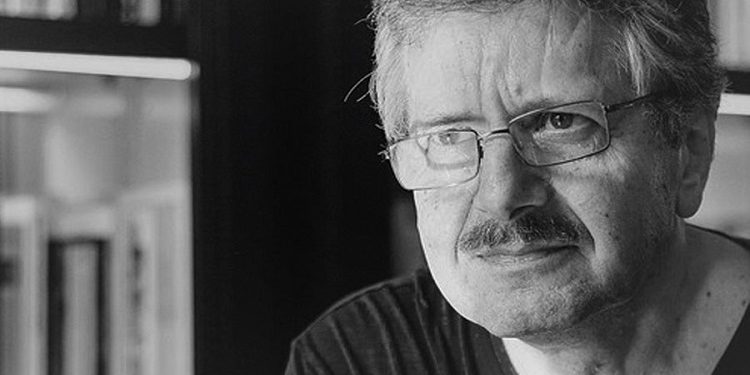

What happened to Nikolla Velço and his life after the night of December 17-18, 1981 – a night that changed not only the fate of Mehmet Shehu’s family but also the lives of dozens of people connected in various ways to the powerful man found dead in his bed?! Furthermore, with the wound of a bullet whose path to the chest of modern Albania’s longest-serving Prime Minister remains a mystery? Although he now lives in France with his wife and two children, those years “when he was hunted like a wild animal” remain etched in the memory of the 58-year-old from Durrës, who frequently visits his hometown.

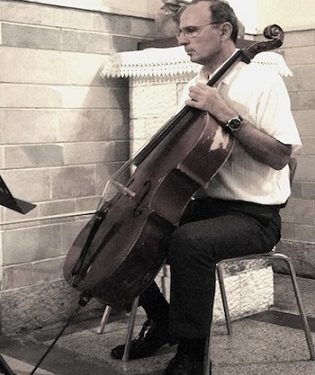

Over 30 years after the event that changed the course of his life, Nikolla Velço recounts his story – a story involving parents, a brother, and sisters, but also witnessing the hell he experienced during the last 10 years of the communist dictatorship. His wife and life companion, the most important person in his life, Anula, his children, his sister’s children, and his friends are all part of his testimony. However, much space is also occupied by a great longing for a non-human object, vital to Nikolla’s life: the story of the cello that was stripped from his hands three decades ago, to which he returned only… 3 days ago, thanks to his willpower and love.

THE CANCELLATION OF THE WEDDING

The Sunday wedding was preceded by what could be defined for the Velço family as “Black Friday.” The country’s Prime Minister, according to the official announcement by Radio-Television and newspapers, had committed suicide. The two columns of the newspaper, read during the 8:00 PM edition of the Albanian Radio-Television, were being analyzed by Albanians in various ways. Nevertheless, the level of uncertainty for the future became even more apparent. Niko’s family decided not to hold the wedding ceremony. At Anula’s house, the ritual had been performed on Saturday, but as the groom of December 20, 1981, recalls, everyone was in a state of turmoil.

TWO TORTURED INFANTS

What was happening? The younger sister, Marjeta, whose proverbial beauty was turning into a nightmare for the whole family, would soon undergo intensive interrogation. Her two young children, Ertgren (two and a half years old) and Regan (11 months old), were brought back by Sigurimi agents after a few weeks, exhausted from Belsh – the place where their parents, Bashkim and Marjeta, were being interrogated.

“We had asked to raise them ourselves, but they only brought them to us when the small children had turned into two skeletons,” recall Nikolla of that terrible period when people would tell him and Anula to their faces: “You are raising snakes!”

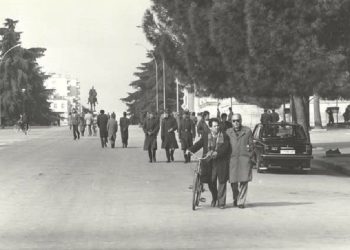

Anula Velço, the young bride who lost her first child before it was born due to these difficult circumstances, along with Niko, their uncle, became the new parents for the innocent children with the “cursed” surname, Shehu. The young couple had settled in the apartment where the rest of the Velço family lived. “It was very heavy,” Nikolla continues. “Below the house, near the photographers’ unit in Durrës, a vehicle stood openly, its receiving antenna visible from afar; there were always spies in front of the building; they multiplied when you went out on the street and became a gang when you needed to go to Tirana, for example…”

12 YOUNG STUDENTS

At the “Hexagon” green bar-garden in the center of Durrës, where we had been sitting for half an hour, Nikolla Velço calmly told us what happened in early 1982 – when, although allowed to continue teaching at the “Mujo Ulqinaku” Music School, he prayed to God to keep his sanity.

“I had 12 young students, but I didn’t have the peace of mind to teach them the cello,” Niko recalls about the beloved instrument those other teacher’s years ago had turned into his life’s purpose. Nikolla recalled the day of his graduation from the Institute of Arts. It had happened just a month before the mysterious death of his sister’s father-in-law, when he performed two works by Antonín Dvořák and Thoma Gaqi before professors and fellow students.

“Every night I had the same dream: I would tense up and could not perform my graduation pieces. When I woke up covered in sweat, I struggled to breathe, and after a few minutes, I would calm down, only to start a day even more terrifying than the one before.”

THE EXPULSION

Velço was expelled from the school 10 months later, in October 1982, when the Durrës city orchestra began rehearsals for a national competition. They took his cello and, with it, the hope that he would ever return to the melodies that had united him with some of the best instrumentalists in the country.

He thought of everything during those first months of his ordeal, which continued with his transfer to the Rubber Industrial Enterprise in Shkozet, Durrës. For any local who knows the “N.I. Goma” of the 80s, the calender department where Nikolla was sent to work was a punishment in itself, amidst toxic substances – but fortunately, also among workers who would become the best friends of the university-educated laborer.

On the first day, they forced him to confess his family’s “faults,” which he never agreed to do. The meeting would have continued indefinitely if one of the workers had not shouted from his seat: “Leave him alone. He’s already in enough trouble! What more do you want?!” Niko says they acted even more despicably toward his wife, Anula.

They removed her from the Faculty of Engineering, where she was in her first year. For days on end, they pressured her, offering a trade “in her favor”: “Leave your husband and you will continue school without problems!” Niko has no words for Anula Afezolli, the daughter of Sotir (known in Durrës as “Thin Tirka”). Anula is not just Nikolla’s wife and best friend; she carries one of the Illyrian names carved in the stones of the 3000-year-old city’s museum. Nikolla cannot find enough words for her and for their greatest wealth today: their two children rose with love in the “time of the communist cholera.”

The 20-year-old woman managed to find work at the Cigarette Production Enterprise as a packager, and the two continued their lives for each other. They lived among people who turned their backs on them, while also distancing themselves from the few friends who sincerely loved them, so as not to harm them.

THE SIGNALS

Nikolla and Anula had each other, but that wasn’t enough. “I don’t know if I could have survived being interned in the villages,” Nikolla says, recalling the mid-1980s. He continued to process all the signals he had experienced during the time when his sister, Marjeta, and her husband, Bashkim, were seen as the country’s “Number 1” couple.

The daughter of Ramiz Alia, a classmate at the Institute of Arts, was the only one who showed distance toward Nikolla – one of the handsome young men considered lucky by others for the new connection his sister had created. “As early as the late 1970s, I realized that Mehmet Shehu was not as powerful as he seemed,” Nikolla says of his former in-law, the Prime Minister.

“I learned that Marjeta, though very young, had one day argued with her father-in-law, and at the center of the heated conversation had been the country’s economic situation.” Marjeta and Bashkim had returned from France via Greece, and the young bride had compared Greek farmers to our villagers, who, with a daily wage of 30 lek, had to spend 40 lek just on bread.

Nikolla recalls his sister’s defiant clothing against the impoverished backdrop of communist Tirana, and despite his brotherly reprimands, he admits: “She was only 20; she had two children and understood little, while her husband almost never spoke to her about these things.”

The final blow of negative news reached Nikolla Velço in September 1981, three months before Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu’s “suicide.” One of the sons of a state official had said in public that “the Prime Minister is not irreplaceable.” While on other occasions Bashkim, his brother-in-law, had not been worried, this time it was different.

“Mehmet Shehu was under pressure, and the blackmail against him worked like an accordion that inflated and deflated. His family members had clearly understood this, and death seemed to be hovering in their home during those autumn months,” Nikolla says.

A COFFIN

The situation grew even heavier for those who knew that a fortune-teller in the outskirts of Tirana had seen at the bottom of Marjeta and Bashkim Shehu’s coffee cup… a coffin. “Aishja was my older sister’s sister-in-law. She lived in the capital with my sister’s family and worked in a school for children with health problems,” Nikolla recalls. He says that some years later, when things had spiraled beyond return, he and Anula also went to see her.

“She would read the coffee grounds only when she wanted to, perhaps in a moment of inspiration or I don’t know what,” recalls Velço of the visits to the house of his eldest sister, Margarita, where Aishja – who never married – also lived. “That evening, she addressed us herself, almost as an order: ‘Drink your coffee, I’m going to read your cups,’ Nikolla recounts. Twenty minutes later, we left my sister’s house feeling relieved, and we lived convinced that good days would come for us as well.” / Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue