By Besim Dybeli

Memorie.al / Who doesn’t want to see beautiful, playful, and dancing women, dancers in discos, pubs, or even at weddings and other celebrations today! They dance in transparent clothes, with bodily movements bordering on seduction. Why not, they are also invited to weddings, either as renowned singers or as rare dancers. They are called modern women. Naturally, of the time we live in. Every generation has those who break the taboos of their time, but we forget that every generation that has passed also preserves a part of the pride of what it was. Thus, century after century and year after year, the term “modern” takes on the meaning and value of the time when it was called such.

This is also the case with the “çingije” girls, a term unknown to the new generation, perhaps even the middle-aged, but for the older generations, they (the çingije) seem to linger in the misty memory of a time gone by. It is a time that belongs to at least two centuries ago. They are the “çingije” girls, beautiful and exceptional dancers.

This category of women, who broke the taboos of the time, appears today, again misty, from the elderly, as there seems to be no genuine ethno-musical study. Our story, which remains more of an appreciative effort, is more related to the period two centuries ago, in the city of Elbasan, despite the fact that Berat, Tirana, or Shkodra were alongside it.

THE ÇINGIJE OF ELBASAN

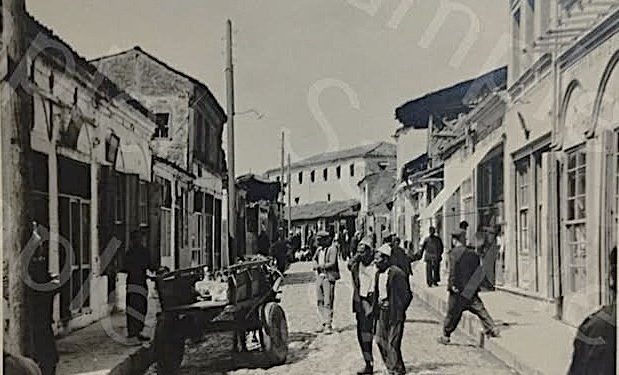

No more than a few decades separate those who still preserve in their memory the fame and reputation of the çingije girls. Their splendor did not last long, approximately a century, where two or three generations interweave on average. Around the years 1840–1940, perhaps beyond, but not later. The Italian occupation seems to have replaced the “empire” of the çingije with the so-called “public houses” of the time, which lasted no more than five years.

But such a replacement was limited only to pleasure or lust, not to musical and dance culture. The çingije, the “prostitutes” of the time, had another mission, which only a certain category of people could understand or appreciate. The majority, the part below the average level of intellect and worldview of the time, would gossip about them to the point of calling them “immoral women.” But they could not help but appreciate them, at least in aesthetics and the art of dancing.

The peak of their prominence in the city of Elbasan covers no more than 50–60 years, perhaps from about 1880–1940, a time when this faded. “I remember that in our city, about three or four groups of çingije were active, competing with each other,” says Rexhep Shabanaj, 86 years old today. “You would love to watch them! Rare beauty and dances that no one else could perform.

We watched them with nezë (envy/admiration), but also away from the eyes of our wives. Our ancestors, who lived this time to the fullest, did the same,” adds Uncle Rexhepi. In Elbasan, according to the time’s reminisces, about four groups of çingije operated, led by the most talented girl, and who were in rivalry to be invited to the weddings or entertainment venues of that era. In a way, like today’s orchestras or more specifically, like singers who are invited to weddings or prominent musical events in luxury venues.

Tushi e Vajes, Sheja e Peqinit, Xhekja e Madhe and e Vogël (Big and Small Xhekja), as well as Tosulla the Macedonian. The groups of girls, consisting of no more than three or four, covered the entire region of Elbasan, but mainly in the city, not excluding the entertainment places called hamame (Turkish baths/spas).

As a novelty of the time, it was naturally imported from the Turkish Empire, both in dances and in clothing, despite becoming a vital and organic part of Albanian society in the most developed cities.

CLOTHES AND DANCES

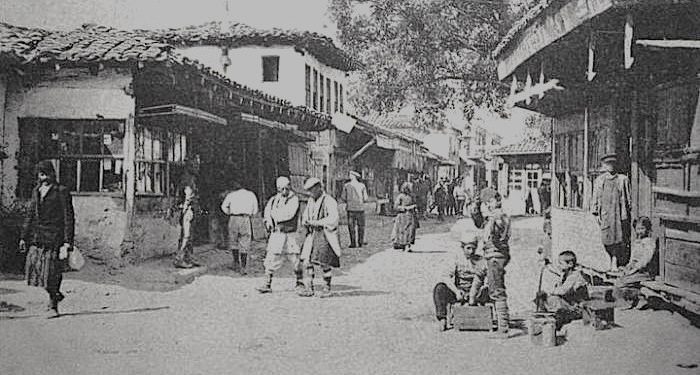

They had the most expensive clothes. The çitjane, also called dimiq (wide, baggy trousers), were embroidered with gold thread or gjymrysh (silver thread), with a somewhat thin cotton fabric, brought from Arab states or Istanbul. According to the elderly, the çitjane that dressed the female body with several folds were so wide that they could hold three or four women inside their size.

They wore light opinga (traditional leather shoes) and white stockings, with embroidered decorations, a vest over the white sleeve which beautifully played the aesthetic role of the female breast’s brassiere, and the most expensive jewelry of the time, while the makeup, among the most accomplished, consisted of solutions mixed with mercury for the cheeks, këna (henna) for the hair, and natural red for the lips.

“They managed to perform fantastic dances that cannot be compared to the ballerinas of the time,” asserts ethnomusicologist Thanas Meksi. According to him, the best çingije had to achieve dancing on a tray. The latter, a large copper, tin-plated vessel, was placed on a round table, where amidst the wedding guests or patrons of this type of venue, the çingije reached the peak of the dance.

Before or after this ritual, the dancing girls danced in front of the wedding guests, mainly men, or even on the laps of the wealthy in the venues. Characteristic was the twisting of the waist, the exposed part of the belly, a part of the chest, and the bodily arching in harmony with the movements of the legs.

To the rhythm of the popular orchestras of the time, the çingije would spend the night with the wedding guests or the selected clients of the bars, and only afterward would they either return to their homes or to secret and hidden places with the wealthy or the intellectual elite of the time. After all, a long, tiring, but also entertaining night, for them translated into large sums of money that the “xhananët” (lovers/admirers) or pleasure-seekers of the time generously threw at them.

NIGHTS OF FLIRTING WITH THE WEALTHY

“They were not prostitutes, despite being called that at the time,” says Abdulla Shabanaj, around ninety years old. According to him, they had chosen this profession, rising above the gossip and shame of the time, and had preferred never to marry in life.

They spent the age impossible for dancing, either with the money earned during their career, or with some other job in bars or family environments. It is learned that while they earned large sums of money at weddings and venues, they refused to take money as a reward for intimate contacts during flirts with the wealthiest or intellectuals.

However, the VIPs of that time naturally would not spare lavish gifts in money, or expensive jewelry. On the other hand, folk creators could not help but weave songs about their glory or beauty. Memories of songs for “Tushi e Vajes” or “Sheja e Peqinit” still reach our time.

“Only the verses from their songs remain: ‘Ulu mal të dali hana’ (Mountain, lower yourself so the moon can appear), or ‘lujma, lujma belin’ (swing it, swing your waist) and others, which are still often performed today in songs with a very old folklore basis,” explains researcher Thanas Meksi. Moreover, this inspiration led the Cultural Center of Elbasan to present the çingije dance at the Gjirokastra Folk Festival.

“We created a dance group only with girls, with clothes like the çingije, camouflaged with the popular style, led by Eser Qatipi, the sister of singer Suzana Qatipi, and due to the censorship of the time, we called it ‘the dance of the single girls’,” says Meksi.

However, a study on the values and affections of the çingije is still missing today. The “çingije” phenomenon preserves the musical values of the time we left behind, and the “inquisition” of opinion for those who broke taboos. / Memorie.al