Albania, a Forgotten People

Memorie.al / Albania are the most backward countries in Europe. Few people want to stay there, and most of its inhabitants, if given a half-chance to leave, would do so in a flash. Desperate in their bid for foreign currency, the country’s communist leaders maintain an official tourism service, “Albtourist,” which is bursting with offers for “rare and unparalleled beaches of the Adriatic” (all of them guarded by police boats that surround you everywhere) and “centuries-old ancient ruins.”

Business seems to have somewhat collapsed for “Albtourist” in its relations with other satellite countries since Albania broke with Khrushchev. “Albtourist” has even sent its tourist files and brochures to a small agency in West Germany, in the city of Cologne.

TIME correspondent Edward Behr decided to apply to go there as a tourist himself. He had to wait six weeks for an entry visa and finally entered Albania, flying aboard a Hungarian airline, “Malev.”

Departing from Budapest, he wanted to get a firsthand impression of a country whose regime was described as “more bloody and more backward than even that of the Tsar” by none other than Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev himself.

Even Socks Must Be Counted

Separated from its only friend in the world, Red China, by 3,000 miles, Albania lives in isolation, experiencing a double sense of defiance and pathos.

More than 70% of its 1.7 million inhabitants make a living from work on collectivized land; most of the farming villages and mountain towns in Albania have changed little over the last century.

Sewage flows through open sewer streams in the middle of the narrow streets; hawk-nosed men sip cups of Turkish coffee in dirty cafes, while their wives carry heavy loads and barrels of drinking water, which is scarce in the country.

Along with traditional poverty, communism posters are firmly fixed with the slogan of Dictator Enver Hoxha: “We build socialism: a pickaxe in one hand and a rifle in the other.”

Even before the final split with Khrushchev, internal security was the highest in the world; since then, it has become a true obsession.

Foreign visitors must fill out forms that detail the contents of their luggage, listing the number of shirts, towels, and socks they have brought with them to Albania.

Albanians are so isolated from the outside world that they are convinced such restrictions on tourists are normal everywhere.

As soon as he arrived in Tirana, correspondent Behr was immediately taken over by officials of the state tourism agency “Albtourist,” who accompanied him everywhere, trying to keep him under surveillance in closed buses.

The agency in question advised him not to conduct interviews or ask questions of government members, actors, or even local journalists; for various reasons, they were either ill, on vacation, or at a funeral because a relative had suddenly died.

Since no foreigner was allowed to rent a taxi in Albania, the government agency was an inevitable and necessary escort. A Japanese reporter who joined Behr was a big help, as he was regularly greeted by Albanians who mistook him for a Chinese person.

Disappearing from the sight of the “Albtourist” people, the two men often, by chance, separated from each other and got lost for a few minutes to see to their own business.

These “escapes” never lasted long, thanks to the vigilant secret police, “Sigurimi,” and other military troops (a quarter of the country’s adult population is in uniform).

Furthermore, local officers and officials would warn visitors, reminding them that they needed to know how to behave, otherwise they would no longer be able to get an exit visa and leave the country without problems—a significant threat in Albania.

Beaches Separated by Walls

An armed detachment in Tirana patrols what the remaining group of foreign diplomats in the capital calls the “ghetto”: the privileged residential neighborhood where the communist leadership has its villas.

Even on the beach of Durrës, Albania’s main tourist resort, 25 miles west of the capital, a wall extends along the sand and into the sea to keep the area restricted and reserved for the privileged, away from the families of workers who share tin-roofed cabins on the other side of the dividing line.

“Proletarian swimmers” cannot go beyond a certain line marked by barrels, which extends 30 feet from the shore; if they do so, a police officer signals them to turn back, preventing a possible escape, by chance, to a Greek or Italian ship that comes to the Port of Durrës.

When a West German ship, which had arrived in the port carrying a cargo of much-needed Canadian wheat-paid for by Beijing-was not even allowed to anchor in the port, the cargo was laboriously unloaded separately without the ship being allowed to touch the shore.

Although Albania has a 250-mile coastline along the Adriatic, fish are scarce there because the government allows only a handful of trusted party fishermen to sell abroad, even though Italy is no more than 50 miles away.

But Albanians are not starving and they benefit from free education, medical service, and other free social services. Behr did not notice any sign of a feeling of revolt in the country when he was there.

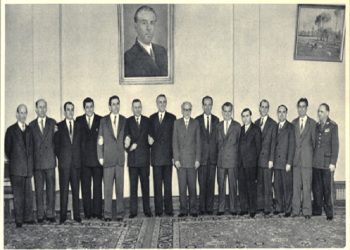

Even if there were, Enver Hoxha’s successor would not have been better; in an open display of nepotism that would make Hollywood envious, the main party leaders are mostly related to Hoxha or Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu.

Combined with the harsh police control is an incredibly unreliable government bureaucracy that requires official permission to buy everything, from medicine to food at hotels. Pedestrians, at least, have an easier time in Tirana.

There are only 400 cars in the country (Old Russian and Czech models, besides a few “Mercedeses” owned by the Chinese embassy); the streets are quiet places where people talk, hug, and sometimes even sleep. You can never find more than three traffic police in total at the main intersections, where they all carry a black and white stick.

Status Symbols from Beijing

As a business center, Tirana looks like a junk market, a bit more expanded within the city. In the nearly 100% state-owned shops, a suit of poor quality costs 7,000 ALL ($140 U.S. at the official exchange rate), or a little less than double what a worker earns in a month of work.

Efforts to industrialize Albania were abruptly halted when Moscow abandoned its half-finished embassy and withdrew thousands of experts last year. The only large cotton processing plant remained out of work for three months; plans for new factories remain on paper.

Of the 22 Russian MIG planes in Albania last year, only five may now be ready to fly, due to the lack of maintenance staff.

Communist China, North Korea, and Vietnam have sent about 500 technicians, most of whom are agricultural workers who teach how to cultivate rice and build cotton processing industries, according to Beijing models.

After work, the Chinese are seen sticking strictly to each other. They eat in a separate dining hall at the Italian-built “Dajti” hotel in Tirana, and live on the grounds of their park-sized embassy, which is constantly protected by guards.

The latest status symbol in Tirana, worn by Albanian communist officials who have traveled to Red China, is now a beige Chinese cloth cap, a favorite of leader Mao Zedong, and black aviator-style sunglasses, also a Chinese model launched by Beijing.

The harrowing poverty, political repression, and mandatory suspicion of foreigners do not make a trip to Albania a pleasant or enticing one. When it was time to leave, correspondent Behr’s plane was an hour late, and even the “Albtourist” agency noticed how happy the departing visitors were. “All good things come slowly,” Behr stammered as he left, waving “Goodbye.”/Memorie.al

“TIME Magazine,” Friday, August 10, 1962, “Albania, a Forgotten People.”

Translated by Armand Plaka