By Dr. Aurel Plasari

Part One

Memorie.al / In the Albanian culture of the first decades of the 20th century, theoretical-aesthetic thought underwent its first qualitative leap, which became especially palpable during the interwar period. As in many cultures with a similar fate, the development of this thought in Albania is characterized primarily by a seemingly permanent intertwining of literary and art criticism – between the history (or theory) of the artistic phenomenon and the analyses inherent to aesthetics as a specialized discipline. The factors conditioning the spread and imposition of aesthetic ideas in Albanian culture during these decades are numerous and complex, often involving contradictory elements that influenced both the dissemination and the expansion of these ideas.

Against the backdrop of a developing consciousness regarding the mission of art in social and cultural life, major works – both cultivated and oral – began to flourish in Albanian literature (more so than in the arts). Responding to the spiritual needs of Albanian society, while naturally stimulating and even provoking them, the literary-artistic creativity of the interwar period in Albania increasingly raised its aesthetic demands, synchronizing itself more effectively with the elevated standards of the modern European artistic concept.

On the other hand, there was also a noticeable peripheral artistic environment, lacking aesthetic criteria, which introduced withered tones and outdated sentimentalism into the perimeter of literary creativity – a burden of misunderstandings regarding the “values” of the so-called “National Renaissance” literature. This formed an éventail (fan) of perspectives that significantly aided in the autonomization of the aesthetic field, opening before Albanian thinkers a dense landscape of problems fraught with pretension, difficulty, and the unexpected.

Historically, it falls to Faik Konica (1876–1942) to be the first Albanian theorist to give momentum to the critical view of works in Albanian literature. He attempted to clarify them, elevate them to the level of critical consciousness, and, above all, grant them a status that was as active and constructive as possible, in accordance with the concrete needs and dynamics of the Albanian culture of the time. Konica was also (historically) the first Albanian thinker to disseminate contemporary aesthetic ideas within culture in general.

I am referring not so much to somewhat known writings such as Kohëtore e letrave shqipe (1906) – considered the founding document of Albanian literary criticism – Albanian Literature, Note on Bektashi Metaphysics, or utilitarian criticism (such as book reviews published in his magazine Albania), but rather to works like Sketch of a Method to be Applauded by the Bourgeoisie (1903), Essay on Natural and Artificial Languages (1904), The Greatest Mystification in the History of Mankind (1904), etc.

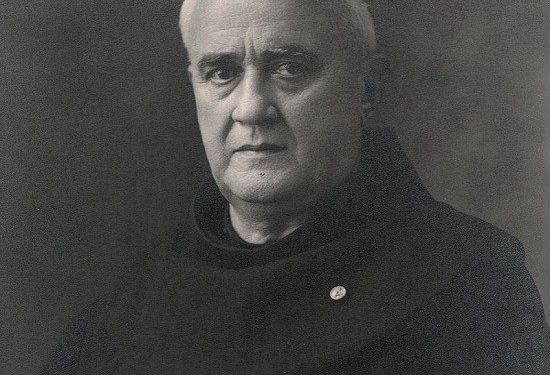

A considerable portion of Konica’s aesthetic thought either failed to resonate particularly within Albanian culture or was not received at all. Subsequently, beginning in the 1910s, it was another protean personality of Albanian culture, Gjergj Fishta (1871–1940), who imposed himself not only as a writer (poet, dramatist, prose writer, etc.) but also as a critic, literary historian, and, specifically, an esthete.

The beginnings of Fishta’s aesthetic thought can be traced to the Preface he wrote for V. Prennushi’s collection Visari komtaar. Kângë popullore gegnishte (Sarajevo, 1911). This writing marks the first period of his theoretical-aesthetic thought, directly linked to his founding of one of the most important organs of Albanian culture, the first cultural magazine in Albania, Hylli i Dritës, in 1913. Starting from the second issue of the first year of this magazine, with the polemical serial Are Albanians Capable of Maintaining a State of Their Own, the polemical impulse emerged as the primary feature of his theoretical-aesthetic writings during this period.

Troubled not merely by a pamphlet-book by a former Serbian Prime Minister (V. Georgevic), but by an entire propaganda machine in foreign newspapers of the time regarding the “backwardness” of the Albanian people, their “low level” of development, their “barbarism,” and especially their “incapacity” to build and live in their own state, Fishta countered this with his own theses. His primary thesis was that the level of a people’s development is measured by the quality of their poetry, their laws, and their customary code – in short, by parameters within that people’s psychic sphere.

To prove this, he employed arguments of a strictly aesthetic order: he examined (and attempted to define) the Beautiful (pulchrum), contrasting it with the Good (bonum); he introduced the principles of harmony, perfection, and order (ordo) into Albanian theoretical-aesthetic thought; he explained the issue of “revival” (something between delectatio and voluptas), highlighting the hedonic component that necessarily accompanies art. He refunctionalized the ancient category of “light,” likely derived from St. Thomas Aquinas’s claritas or the splendor of the Scholastics. Speaking of a specific capacity for aesthetic perception, he touched upon forms of the relativistic theory of taste developed by the (English) empiricist tradition; here, his concept of the “mind’s eye” recalls the “moral sense” or “inner eye” of the Earl of Shaftesbury, or F. Hutcheson’s “sense of beauty.”

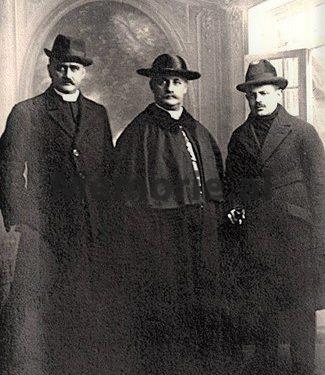

Arguments of the same order were utilized to defend the cultural identity and civilizational development of the Albanian people in the Preface to Visari (1911), and would be used in the text The Albanians and Their Rights, written by Fishta in Paris (1919) to be delivered by Monsignor Luigj Bumçi at the University of that City.

It was also during this period that his contribution to literary criticism began, with reviews in Hylli i Dritës (and for a two-year interval in Posta e Shqypnís) of various works, primarily Albanian literature. Possessing a classical structure, he began in the field of literary criticism to clarify – directly or indirectly – a series of fundamental concepts, emphasizing the effort to integrate Albanian literature, criticism, and history into the system of universal values.

The second period, roughly emerging in the 1920s, also maintained a palpable “polemical impulse,” but it now functioned internally. This period began with writings such as The Rebirth of Spirits (1921), The Catholic Church Formed Western Culture (1923), etc. It can be characterized as a period of expansion for Fishta’s aesthetic interests, evidenced by works like The ‘Vatra’ Federation and Music (1923) and the unfinished sketch On the Five Orders of Universal Architecture (1920s).

Transcending general aesthetics, in both works, Fishta studied the concrete manifestation of the arts, turning his inquiry into a study of form, technique, and the spiritual content of creation and contemplation within the specific frameworks of music and architecture. In this second period, Fishta’s artistic interests extended into practical activity. Aware that the national existence of a country is directly linked to its artistic existence, he personally engaged in theatrical organization (as a director), architectural projects and realizations, and even participation in painting exhibitions.

A third period, which might be termed “the 1930s,” also began with polemically conceived writings. However, this conception now served openly as a “pretext.” Realizing that artistic creation in Albania (especially literary) had reached a stage requiring principled clarification and the promotion of specifically aesthetic coordinates, Fishta set out to offer a more nuanced and flexible model for judging aesthetic value.

He aimed to achieve this through polemics such as A Mute Assassination (1930), To the Shadows of Parnassus (1932), The Albanian Heroic Verse (1935), etc., via prefaces like those for The Great Poets of Italy (1932) or The Code of Lekë Dukagjini (1933), and various essays, the peak of which was On the Occasion of the Centenary of the Death of Wolfgang Goethe (1932). To seek the aesthetic principle now meant for him: to confront masterpieces and derive from them the laws for future creations.

Working to give the act of evaluating literary (and artistic) work flexibility, subtlety, and rigor, his theoretical writings of this period became exemplary. Following the norms of classical rhetoric, his aesthetic and critical texts announced essential truths through unexpected formulas. It is possible that an innate oratorical ability, or one trained by his profession as a preacher, led him toward constructions with perfect regularity, perceptible at the deepest level of idea communication.

Such constructions function as stylistic canons (captivating with their whim and vitality) to hold the audience/reader’s attention through digressions, plastic figures, metaphors, and associations, testifying to a formidable mental mobility and a great cultural weight, with open references to the field of arts.

Some of his assertions from this period may be subject to criticism; however, we have the right to think that Fishta conceived his aesthetic and critical “sermons” sententiously, without always insisting on explaining every thought, precisely to stimulate discussion – or even the re-discussion of values – from a personal perspective through a personal critical act. Since the “classicist’s” tendency is to formulate sentences, his expression sometimes becomes apophthegmatic; in such cases, it is not the truth that matters, but the sentence itself.

(This may be difficult for modern readers to grasp, for whom a propositio is no longer, as in the time of the Latin rhetorical tradition, a “sentence” in grammar and, simultaneously, a “premise of a syllogism” in philosophy.) In writings of this period, he appears possessed by a playful spirit (frymë ludike), by a speculative dreaminess that sweeps one away. But it is a game to be understood at the highest level – the classicist level – dealing with previously unformulated, provocative expression and associations pushed to the point of inciting reaction.

In this period, his critical creativity, regardless of its form, became laden with philosophical weight. The masterly essay On the Occasion of the Centenary of the Death of Wolfgang Goethe (1935) serves as a striking illustration of this weight. Precisely distinguishing the fields without making it his task to transform criticism into aesthetics, Fishta did not hesitate to use concepts akin to philosophy when discussing creation, freedom, invention, imitation, feeling, taste, etc. At this point, the criticism/aesthetics relationship in Fishta’s case poses a problem that may never again be raised in the history of Albanian culture: “philosophy and criticism” or “the philosophy of the critic”?

Fishta appears in this culture as the archetype of the artist for whom criticism is philosophy. It seems as if Croce formulated for him the principle that the critic, at the end of his investigation, should attempt to summarize his judgment in “a formula” that remains open, so long as a further process of analysis that modifies the formula is never excluded. In almost no case did Fishta aim to impose a “canon” or a rigid model on readers to be followed with obedience.

In this way, Fishta occupies a place in the history of Albanian literature as one of the first critics to understand that, for example, the figure is also a feeling. Rising above empirical evaluation, his critical discourse gains scientific value in itself. His “formulas,” though representing an individual opinion rather than universal knowledge, become the synthesis of a taste because the critic works to provide a scientific foundation for his opinion. The interest of his research lies not in the opinion, but in its foundation. Whether Fishta finds Faust not to be the protagonist or Goethe’s masterpiece to lack organic unity matters little; what matters is the foundation he provides for these judgments.

Thus, Fishta the critic also becomes a philosopher of the work of art; but not only a philosopher; he also becomes its philologist, its historian, and its psychologist. One must remember that, particularly in the 1910s and 20s, the Albanian critic limited himself to writing the history of the poet and his work, establishing links between artist and creation, or wandering through lexical comparisons – hardly distinguishing himself from a general historical or philological researcher. There was little difference, in such cases, whether the subject was a poem or a parish registers. Through his approach, Fishta offers not only an example of the creative act called criticism–literary history–comparative studies as facets of the same process of recovering significant literary values, but also a lesson on the sovereign freedom of the artist’s spirit and the ability to transcend the boundaries of conventional thinking.

His most important achievement in this field, not only for this period but for Fishta’s entire theoretical-aesthetic thought and perhaps for the tradition of Albanian aesthetic thought itself, is Aesthetic Notes: On the Nature of Art (1933), published in two installments in Hylli i Dritës and then interrupted. The general level of such a theoretical undertaking, with the pretensions of an aesthetic treatise, aims toward a complete detachment of the aesthetic phenomenon from other adjacent spiritual spheres; it is a grasp of the specificity of this phenomenon and, simultaneously, the normalization (through the critical act) of artistic and literary creation.

The need for such a detachment of the aesthetic phenomenon from a conglomerate of heterogeneous phenomena seems to have been understood before Fishta only by Konica, whereas De Rada was not conscious of it in what he called Principles of Aesthetics (1861).

The fate of the work Aesthetic Notes in the history of Albanian aesthetic thought strangely recalls the fate of a famous treatise in the history of global aesthetic thought: the so-called “Pseudo-Longinus.” We call the work On the Sublime (Peri hypsous or De sublimitate) by this name, which was mistakenly attributed to the Hellenic philosopher Longinus (c. 210–273). Even after it was proven that the treatise was not his, the true author – likely a Jew of the Alexandrian diaspora – remained undiscovered.

Fishta’s Aesthetic Notes, signed with the initial A., remained unmentioned as his for a long time. Even in his text Directions and Premises of Albanian Literary Criticism 1504–1983 (Prishtina 1983, Tirana 1996), I. Rugova, while describing the Aesthetic Notes published in Hylli i Dritës, failed to identify the author (pp. 365–366). Two pages later, describing a 1941 article by K. Prela in the same magazine, Rugova writes: “We are led to believe that this author, Kolë Prela, may also be the author of the article ‘Aesthetic Notes’… We say this based on the identical language and terminology of these two works” (p. 370). This is a startling observation, given that the “official” bibliography The Literary Work of Father Gjergj Fishta, compiled by the writer’s Franciscan brother Father B. Dema and published in Hylli i Dritës, explicitly identifies Aesthetic Notes: On the Nature of Art (1933) as Fishta’s work. To assume Rugova was unaware of this bibliography? One cannot, since Rugova himself describes the bibliography in detail on page 350 of the same book: “37. At Benedikt Dema: Vepra letrare e At Gjergj Fishtës.”

Is it the same Rugova who wrote pages 348–350 and pages 365–370? Unless he explains it himself, this will remain one more mystery regarding Fishta’s work. I recall in passing that an esthete like J. Mato, when writing on Fishta’s aesthetic thought (in 1996), had no difficulty identifying the authorship of Aesthetic Notes.

Longinus’s treatise, likely written in the 1st century AD, survives today via a 10th-century manuscript, fragmented and unfinished. The text of Aesthetic Notes, begun by the author twice (in 1932 and 1933), also remains unfinished. We do not know if it was never finished or if it remained partially unpublished and the rest of the manuscript is lost. Historically, we only know that from that year (1933), the author was forced to leave Albania due to a “quarrel” with the state: under the pretext of closing “private schools,” the Franciscans’ renowned lyceum, directed by Fishta he had been closed!

Habent sua fata libelli, the Latins used to say: Every book has its own fate. One can only express regret that such a “fate” befell a work like Aesthetic Notes. The first known edition of Longinus’s treatise is the Latin one of 1554. Two thousand years have passed since its writing, and whoever reads it today is amazed by the vivid spirit it brings. It is a two-thousand-year-old work that smells nothing like scholasticism or old libraries. More than sixty years have passed since the publication of Fishta’s aesthetic treatise, and its reappearance today cannot fail to surprise with its freshness and originality of thought.

The emergence of the unknown Hellene in the 1st century can be called a miracle, so far above his time did “Longinus” stand. Yet, the first edition we know (1554) passed almost unnoticed. His thought was therefore called a “spark that ignited nowhere.” Something similar can be said for Fishta’s treatise and its role in Albanian culture. That Antiquity once engaged in a conspiracy of silence against “Longinus” is one of the clearest symptoms of the decline of intellectual power in that fading epoch. / Memorie.al

(Original title: FISHTA MEDITANS)