By Makensen Bungo

-The confession of the former political prisoner, Makensen Bungo, to Prof. Et’hem Haxhiademi and the unknown letter he sent to Lasgush Poradec on April 9, 1938!

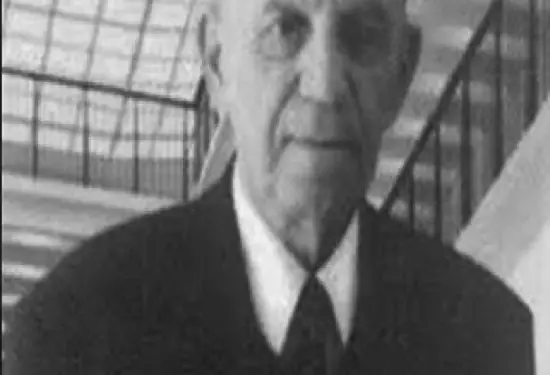

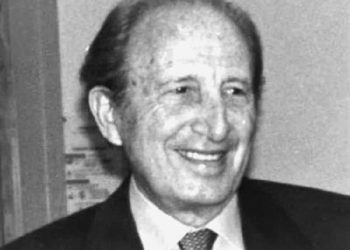

Memorie.al / At the great table of Albanian writers of the time of Independence, Et’hem Haxhiademi occupies an honored place as a playwright. In the group of Albanian patriots, he is mentioned for his pure feelings as a republican, for his consistent attitude in the fight for the liberation of the Motherland and for his manly attitude in the prisons of the communist dictatorship. Among the people, he is distinguished for his pure spirit and his big heart. We young people from Elbasan, who had just started the difficult but beautiful path of literature, honored and respected Et’hem Haxhiadem, we read his works with pleasure and, as fellow citizens, we were proud of him.

I first met the poet-playwright Et’hem Haxhiademi during a visit I made to him with his nephew, at his house, at the beginning of 1946. I was impressed by his warm welcome, the free conversation he had, his love and the interest he showed in us and the instructions he gave us. Two, were his advices: to read as much as possible and to learn a foreign language. I must add that during the conversation we had, he told us that, when he was a student in Austria, he had written an erotic novel entitled “Tyrbja e Goca”, the manuscript of which he had lost during the trip, when he had returned to the Motherland. I note this detail because until now, the authors who have dealt with this writer have not mentioned this work.

It is known that Et’hem Haxhiademi spent twenty years in prison during the communist dictatorship. He was arrested in 1947, in the middle of the night, in his home, when he was correcting the students’ essays, because then he had been appointed a literature teacher at the “Normal” School in Elbasan. From home, they took him straight to Tirana, where they kept him in the investigation there for months, amid terrible torture.

They accused him of reorganizing the “Balli Kombëtar” organization. From here they returned him to Elbasan to judge him. When the president of the Military Court pronounced his death sentence (as Abdulla Mema told me, who was sentenced in a court session with him), Et’hem Haxhiademi shouted: “Long lives Albania”!

Those sentenced to death were kept with handcuffs until the approval came from the Supreme Court and they were no longer tortured. With Et’hem Haxhiademi, the opposite happened. Although he was sentenced to death, he was brutally tortured again and again, almost every night. They tortured him so much that he became so weak that when he was allowed to go to the bathroom, he no longer had the strength to walk by him, but held himself against the walls of the corridor, and finally, when he was completely weak, he began to drag himself.

They did not shoot him thanks to the intervention of the Dictator of prof. Aleksander Xhuvanit and prof. Kostaq Cipos. In this serious state of health, he was sent from the dungeons of the investigation to the “Prison of Enemies of the People” in Elbasan, where they kept him for almost two months with his hands tied with iron handcuffs, day and night, without removing him for a single moment. They announced the end of life too late

After a long time that he was kept in Elbasan prison, he was sent to Gjirokastra Castle and then to Burrel prison, where he died on March 18, 1965, six months before serving his sentence. His relatives suspect that his death was not natural. For the dictatorship, this man was not supposed to get out of prison alive.

In 1991, I started collecting material to write a monograph on Et’hem Haxhiademi. I had read his works, I had learned about his patriotic activity, I had lived with him for a long time in the dungeons of the investigation and in the “Prison of Enemies of the People” in Elbasan and, above all, I had a trust that he had for me leave this great dramatic poet in the most critical moments of his life.

Among the materials I collected, his son, the eldest, gave me a photocopy of a letter that Et’hem Haxhiademi had sent to Lasgush Poradec, in 1938, at the request of the latter, because he wanted to draft – as he told me biri – an anthology on the most mentioned Albanian writers of the time along with their biographies.

Here is the letter:

I took it in Elbasan

Today, April 9, 1938

Lasgush Poradeci.

NOTES ON MY LIFE

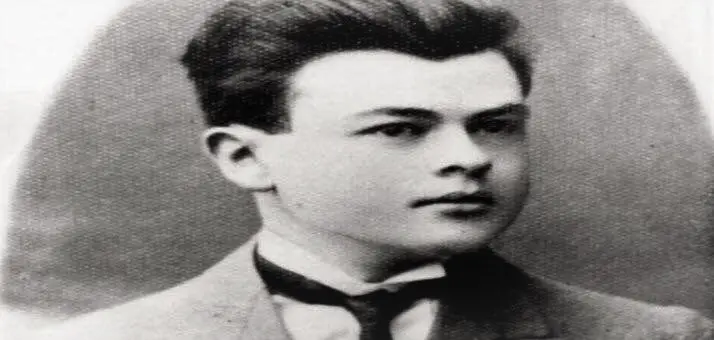

I was born in Elbasan on March 8, 1902. My father, Emin Haxhiademi, whose patriotic activity began as early as 1877, that is, before the Congress of Prizren (as mentioned by the 25th anniversary commission in the biographies of the patriots of which were not published by the government), is known in Elbasan as a close collaborator of Kristoforidi and the second patriot, after him, in seniority in this city. From my age, I secretly learned the Albanian language, before the announcement of Hyrriet and, when the first Albanian school was opened in Elbasan, around 1908, I was the first student to enroll in that school.

(The first Albanian school opened with the initiative of some Albanian patriots, headed by my father. I also have the original of the congratulatory telegram that Faik Konica sent him from London some time ago and the answer that my father gave him). Like all those who dealt with the Albanian issue and mine, he used all the Albanian books, magazines and newspapers that were published at that time, arranged in a special room where I often stayed, because I learned Albanian and fed on those publications small but quite rich for that time and for my young age.

One day between the books, I got hold of the drama translated from Turkish by Sami Frashër “Besa”. As I sang it a little at the beginning, it touched me a lot and so I closed myself in the room until I could sing it to the end. I liked it so much at my young age that I filled my eyes with tears and since then, my interest in theatrical works remained in my mind. The effect of that time has remained with me even today on the drama “Besa”, so much so that although I see many main flaws as a work of art, I still like to sing it because it is related to the memories of my past time.

One day (I must have been 14 years old) I sat down at a table and started to write a play, of course, with a national subject, as was the time. So I stayed for days in a row and sometimes the line and the school without attending. When the people of the house asked me what was wrong, I didn’t show it. In the end, after almost two months, I finished my drama (!) and I told it to my father, who was naturally capable of judging. So when I approached him and told him that the church had written a play, he greeted me with an ironic smile and didn’t even want to sing it, but later, my mom’s prayers on one side and his curiosity on the other, he started singing.

My heart was pounding and I eagerly awaited his judgment. In the end, he called me this time, not with ironic laughter, and told me that I was still young and that he wrote a dramatic work for me, it’s not a small job for the poor. You should have seen me finish school, study the dramatic works of great foreign poets and then retire to the theater. So what you wrote, my deceased tells me, is laughable and deserves to be burned. When I hear these words from him, I was very happy. I took my work like that and at first I kept it carefully among my books, but later I obeyed the father’s advice and one day I burned it. Despite all this, my extraordinary desire to become a dramatic author never faded from my heart.

I did quite well at school. I followed all the lessons with interest. From the time I was little until I left the Motherland and went abroad to study; year after year I came out first in the class. After 1919 I went to Italy, to the city of Lecce. We stayed in a dormitory with some 60 Albanians in addition to the Italians, and I was preparing for the fourth year of high school, while the Albanians were in the lower classes. When the exams were held at the end of the year, it was the most unfavorable time for the Albanians, who were hated by the Italians because of the Vlona war. At the end of the exams, I was the only one who passed the class out of all the Albanians, all the others left one or two subjects.

To confirm my words, you can ask Mr. (unreadable name), who was one of the Albanians who was preparing for the second grade of high school and he stayed for the fall like all the others. So if he is honest, even if he has an enemy, he must tell the truth. In Lece, I had a very good professor who prepared me for the Latin language. When one day he was preparing Virgil’s Bucolics for school, he saw that I was quite impressed by the beauty of the work.

He asked me with a smile if I like them. I told him that when I learn the Latin language well, I will translate this work into Albanian. And indeed, after three years, I dealt with the return of Virgil’s “Bucolics”, which I returned not entirely to the original version, in hexameter. As a basis for the use of hexameter in Albanian, I took as a model the translation of “Bucolics” in the German language by Vossi, which is also in hexameter, taking for dactyla and sponde not the length of the syllables as in the old ones, but the accents.

These types of hexameters based on syllables in German (as you also know), besides Vossi, in the translation of Homer and Virgil, Goethe also used them in ‘Hermanin und Dorothea’. So with the translation of “Bucolics”, I believe that I did two services: 1) I am the first to translate a Latin poet into Albanian, 2) I am the first to use the hexameter in the Albanian language, according to the models I mentioned above. (Regarding my use of the hexameter, see also the newspaper ‘Demokratia’ of Gjirokastra No. 453 dated March 3, 1935).

I attended upper secondary school classes in Austria. In Tyrol, I also passed my matura and entered with a complete knowledge of Greek and Latin literature. The Greek and Latin authors were not sung by me enough to pass the class, as most students do, but with great thirst. After the knowledge of the Greek language, I was not enough for the authors of the book, as a culture I also used the translations in the German language.

After 1924 I was in Berlin and attended university classes in that city at the faculty (word that cannot be read), against my will and as per the wishes of my parents. At this time, I almost knew well not only Greek and Latin literature, but also German, French and Italian literature and from English, Shakespeare, the latter with the translation of (unreadable name).

One day when I was singing Homer’s ‘Odyssey’, I saw that Homer brought the end of the work to the end of the adventures of the fate of Ithaca. I was interested in finding out what was the fate of this fate everywhere and I found in (words that cannot be read), that Ulysses, who killed his son Telego, without knowing him, was robbed of his fate. This is why I am interested in dealing with my first tragedy ‘Ulysses’; I believe that it is suitable for a tragedy in the spirit of Aeschylus. This subject, as far as I have investigated, is not used by any writer until today, except that Aristotle mentions in his work “Poetics” that this subject was treated once by Sophocles in the lost works. Then Greek history, Greek culture and especially the tragedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides had taken my heart, they had me for themselves.

So I ran and wrote my first tragedy ‘Ulysses’, I worked on it and reworked it for a long time. The first time I wanted to include choruses, but later I believed that choruses cannot appear on stage, so I left them, just as other writers who follow the footsteps of Greek tragedians such as: Corneille, Racine, even Goethe, in ‘Ephigenie auf Tauris’. As a verse, I liked the iambic pentagrams of (words that cannot be read), but I rhymed them to give them more music and were influenced by Corneille and Racine. The structure of the tragedy, woven according to the Aristotelian theory, is used in three parts, like the French and Greek classics.

It is true that today the Aristotelian units have only a historical value, but it seems that in the tragedies with old subjects, they still remain as an ornament. And Goethe, who was one of the insurgents of Sturm und Drang, in his dramatic works as a boy, but when he wrote ‘Iphigenin’, at a later age, as after the subject, he used all three. The theme of my tragedy ‘Ulysses’ is man’s struggle with fate. What was said by the oracle will be fulfilled and man has no escape. This is also shown by Sophocles in ‘Oedipus the King’, this by Schiller (words that cannot be read) and here by me in ‘Ulysses’.

In 1926, I came to continue my studies in Vienna, then in Berlin, with the exit (words that cannot be read), life became easier especially for me because I had no subsidy from the state and I was supported by the house. One day it occurred to me to weave a second tragedy, with the protagonist of Homer’s ‘Iliad’. Even the ‘Iliad’ takes Achilles to the point where he kills Hector (words that cannot be read), saying that Achilles was killed by Paris, Priam mistakenly believed that he would marry him, and give him his daughter Polyxene, with whom Achilles had a boyfriend So I went to work and after a lot of work and rework in the system of ‘Ulysses’, my second tragedy ‘Achilles’ came out. The spirit of the “Achilles” tragedy is revenge. Every man who kills no matter how strong he is will suffer in the end. We find such a thought in Aeschylus’ Agamemnon and Sophocles’ Electra.

Here in Vienna, I also collaborated with the magazine ‘Djalërija’. This is the second magazine where I collaborated regularly. For the first time I collaborated in the “Literary Garden” with 1918, since the age of 16, naturally with light items. I also published my first lyrical poems in ‘Djalërija’. (See No. 1, vol. II, year VIII, dated May 1927). The most beautiful of this in this issue is the one with the title ‘Galates’. This is an elegy for a dying girl. (You wrote me on paper and for notes (words that cannot be read), you felt it yourself and take the ones you like). The death of a girl, whom I loved deeply, shocked me and so I made a small memory of this elegy, with the title of a fascinating name, ‘Galates’.

At the end of 1927, I returned to Albania and after 1928, I was appointed sub-prefect in Lushnje. Here I was reading Plutarch one day, I was interested in the story of Alexander of Math, how he became king and how his father Philip was killed, due to the rivalry of his two wives. So after a long period of work, the tragedy “Alexandri” came out, the third tragedy in terms of number, but the first in terms of value, after “Ulysses” and “Achilles”, traces of boyhood are still known. In 1930, when the theatrical competitions were held in Tirana, the philodrama group of Elbasan, performed my “Aleksandrin” and received the King’s award. Although the group from Shkodra and Korça were better prepared from a stage point of view, but as the newspaper “Ora” said, then Elbasani won the award only for the beautiful work they presented.

The tragedy “Alexandri” is the tragedy of rivalry. It shows that two women marry a man, where they lead a family and to what misfortune.

Between 1933 and 1936, I was in Gjirokastër as chief secretary of the Prefecture. After 1933, there I wrote the idyll ‘Nymphs of Shkumbin’ which I published in ‘Illyria’ No. 4, dated March 25, 1934 and No. 5, dated April 1, 1934. I brought the Nymphs and Muses of ancient Greece from Parnassus in Shkumbi, they bathe and sing through the woods along its edge, until the Albanian hunters, who do not understand the value of their kanga, steal them. Isn’t this an Albanian event?!

Also in Gjinokastra, where I sang the life of Pyrrhus from Plutarch, in 1934 I dealt with the fourth tragedy ‘Pyrrhus’. This is my work, I love it and I firmly believe that it will remain the masterpiece of Albanian Melpomena for a long time. (Please sing it all). Here again I wrote the Elegy ‘Black Night’, published in ‘Illyria’ no. 8, April 29, 1934. Here I mourn the death of my mother, whom I love more than anything in this world. I wrote the ode here, ‘Naim Frasherit’, published in ‘Illyria’ no. 16, 24 June 1934.

In this ode, I praise the value of Naimi as a poet and patriot and I call on the Albanians (I am the first to do this), to collect the remains of this man and bring them to the Motherland. I later wrote the poem: “The fight of the dragons with the kuchedre”, published in “Illyria” No. 22, September 14, 1935. Based on the popular saying that, when it rains, the dragons fight with the dragon, I composed this poem as a ballad.

Of my lyric poems, I will mention only these, as most of them have not seen the light of publication. Now I will soon publish them in a special volume, but for my dramatic works, they deserve to be discussed differently. After 1935, I wrote the tragedy “Skenderbeu”. This is the tragedy of envy. Envy brings individual tragedy and national tragedy, as this is elaborated in my tragedy, where not only the tragedy of Skanderbeg is shown, but of the entire Albanian people. After 1936, I wrote the sixth tragedy; ‘Diomede’. This is the tragedy of love. Love is unbreakable. Going in the opposite direction, brings the most terrible thing to kill brother after brother, as in my tragedy.

In short, and as you ordered, on these pages, this is my artistic life. In the letters you sent me, you gave more importance to lyric poems. But for me, the greatest importance is my tragedies. The drama has found its end in me; just as the lyrics have found you and the novels have Koliqi. So my tragedies: 1) ‘Ulysses’; 2) ‘Achilles’; 3) “Alexander”; 4) ‘Pirrua’); 5) ‘Skenderbeu’; 6) ‘Diomedes’, although I briefly described their contents, but if you wanted a complete opinion, you should sing them, especially the last four and especially ‘Pirrua’, which, as I said above, is a work I love mine.

In all my tragedies, the same technique that I mentioned in ‘Ulysses’, that verse, and that dramatic weave are used. As per your request, I am sending you 6 tragedies and “Bucolics” by mail. For the lyric poems, I have referred you to the newspapers and magazines where they were published, until they were published as a book. I have noted only 5 poems; the others were not even published in the newspaper. And the fifth ones, they are not only rhymes, but I can say that they are long poems. Only ‘Galates’ is a short elegy.

Now we will see the judgment that you will make yourself. As per your order, I am sending 10 pages of notes. How to sing these and the works that I am sending you, I believe that I am not in the (unreadable word), with friends, but I am in the dramaturgy branch, like you are in the lyric and Koliqi in the novels. (Two lines illegible). I have never been in the habit of boasting, but just because you asked me, I am sending them. Be fair in judgments.

So thank you.

This is the letter, which I am publishing without any changes. I do not know whether this letter has been previously published in any organ, nor do I know where the original is to be found. I am publishing it to help future biographers and researchers who will deal with his life and literary work. It is for this purpose that I am publishing these few notes on the sufferings of this writer in the investigation of Elbasan, which are more than true, because I myself was in the investigation at that time.

On this occasion, I want to remind his city of the appreciation and honor that should be given to the figure of this outstanding poet and patriot. Elbasan, there is the monument of the great patriot and linguist Kostandin Kristoforidhi, there is also the monument of the patriot Aqif Pashë Bicak, the right arm of Ismail Qemali, there is the bust of the patriot and philanthropist Ali Agjahu, there is the bust of the patriot, linguist and teacher, Aleksander Xhuvan, why not have, among them, in front of the Shkumbi nymphs, the monument of the patriot and poet-playwright, Et’hem Haxhiademi? Memorie.al