Memorie.al / The life of Adem Beli, one of the important Albanian agronomists, told through the descriptions of his son, official documents, and meaningful photographs. A life divided between valuable contributions in various sectors of agriculture and inhumane tortures in the cells of the communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. Electric shocks to his ears and blows to the soles of his feet left him with irreparable injuries, yet after his release from prison, he continued to serve wherever his knowledge and experience were needed! Tulips and Gladiolus were successfully exported to the Netherlands, but they could not “speak” of the tortures inflicted upon their agronomist, nor the injustices of the land where they grew.

Who would have thought that the Netherlands of Tulips, in the 1970s, imported some of its symbolic flowers from Albania! Along with the tulips, irises, hyacinths, lilies, and gladiolus…! Their cultivation was supervised by the Experimental Station of Floriculture, whose technical director in 1971 was the agronomist Adem Beli. Adem was assigned to this station, which turned out to be very successful, to complete his years of work, as he had retired early due to health reasons resulting from the years he spent in the cells of the Security and the camps and prisons of the communist regime in power.

The main concern was his feet, which, previously gangrenous from torture in the interrogation cells and working to drain the Maliqi marsh, had worsened from walking, the rough terrain of the agricultural cooperatives where he was assigned for work, and the rubber boots that he wore throughout the years he served in the villages.

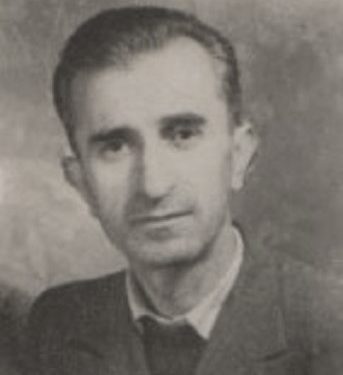

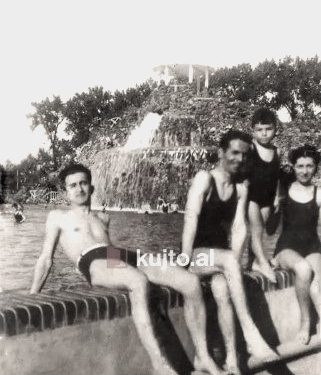

As stated in his biography, provided to us by his son, Arben Beli, the house where Adem was born in 1909 in Korça was one of the centers of the Albanian National Movement, near the hearth of which distinguished patriots such as Sali Butka, Mihal Grameno, Spiro Bellkameni, and others gathered.

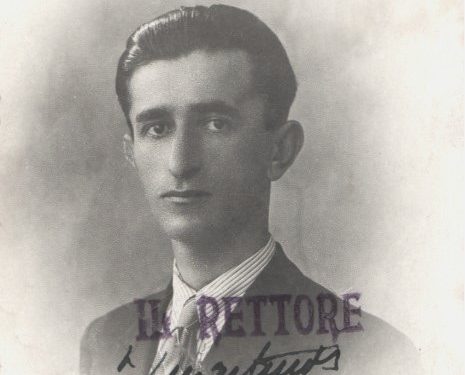

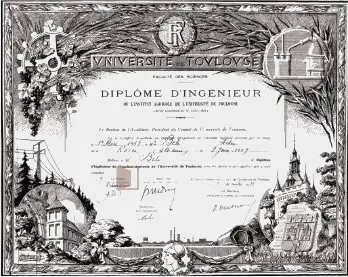

He was one of the excellent students of the French Lyceum, where he began studying in 1921 and in 1924 started at the Royal Military School in Tirana, which he finished in 1931. He worked for a short time as an officer and at the beginning of the academic year 1935, started attending the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine in Italy. He completed the first year there and moved to the University of Toulouse in France, where he trained as an agronomist.

He graduated in 1939 and at the end of that year returned to his homeland. Adem was an active young man who got involved in anti-fascist activities and helped raise financial contributions to support the Civil War in Spain while he was in Toulouse and Paris.

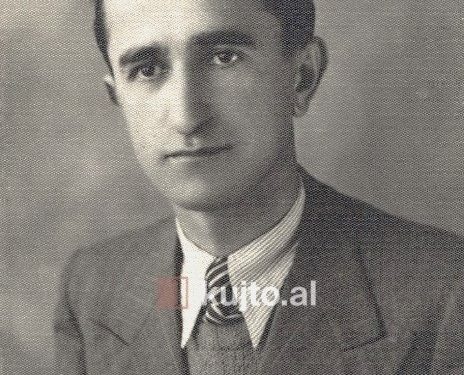

In Albania, he was appointed chief inspector of agriculture in the prefecture of Vlorë. He had nationalist ideas for a Western liberal democracy. Even here, he continued to be engaged in scientific work and national developments. While dealing with the cultivation of olives on the coast, his office in Vlorë became a center for organizing anti-fascist demonstrations.

He collaborated with the nationalists Skënder Muço and Hysni Lepenica and participated in the battle of Gjormi, as well as in other military actions. However, the climax of his tension with the Italian occupiers reached a peak when he refused to sign the sale of aviation land to them. His name was added to the list of internments in Ventotene, from which Adem escaped by going underground.

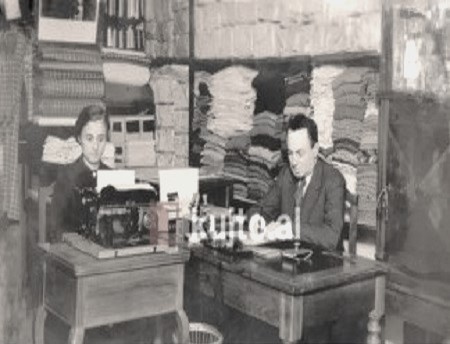

In Vlorë, he left behind an accurate database for every olive tree, constructed according to the French model. Not only that, but he also organized the work for the construction of the First Synoptic Station of Vlorë. After October 1943, he returned to duty as the chief inspector general of the Ministry of Agriculture.

After the war, when Albania was preparing new cadres in various sectors, Adem Beli directed the first courses for training mechanics, tractor drivers, and agricultural managers at the Xhafzotaj farm, since he had obtained two additional diplomas in Toulouse for tractor driving and agricultural machinery operation. Later, he was transferred to Berat, where he was engaged in the serious problem of locusts that were destroying the crops of that period.

The Dark New Years

He had only been back in Albania for seven years when he was arrested. He was handcuffed on December 31, 1946. The next day would mark the beginning of a year and a new life for him, the opposite of what people usually tend to optimistically hope for at the beginning of a year. Not only for him but also for his family. At that time, Adem had married Shadije Alizoti, and for two years, he had become a father to a daughter.

Adem Beli was accused of treason in collaboration with the group of deputies led by Riza Dani. The 37-year-old experienced some of the most brutal tortures from the manuals that had fallen into the hands of the Albanian interrogators: electric shocks with wires placed in his ears, blows with sticks to the soles of his feet, being suffocated in a cell filled with water, where, due to open and untreated wounds, most of his fingers began to be amputated. For an entire year, the interrogators, led by Nevzat Haznedari and Stavri Xhara, did not tire of torturing him. They would only release him when the stench of his gangrenous feet became unbearable.

They were not only after his body but also his spirit. They psychologically tortured him by taking him to an unknown place, where they placed a noose around his neck, threatening to hang him if he did not reveal his accomplices. They put spies in his cell…! Nevertheless, he never opened his mouth.

The accusation against him and a whole group of arrested individuals was that they “had formed committees of the ‘National Front’, that he had executed the decisions of the Central Committee, collectively and through UNRRA officials, they had connected with criminals who had fled to Italy, such as Mid’hat and Mehdi Frashëri, Ali Këlcyra, etc., from whom they received instructions and assistance and provided them with information.”

The strong moral character, the stoicism that stemmed from familial and patriotic values, and faith in God gave him an unimaginable strength to resist all their attempts to make him admit guilt. He had to wait for execution, which had been promised to him more than once, but when he went to trial in January 1948, he was sentenced to 20 years of imprisonment and forced labor, accused of “organizing committees against the people’s power.”

The merit for the change in the indictment and the sentencing decision was due to the intervention of his father-in-law, Ali Demir Alizoti. His name appears in early descriptions as one of the founders of the Knitting Factory in Korça, where Koçi Xoxha’s wife had been the technical director for several years. This old acquaintance caused Adem to be spared his life, but it was not the only intervention that magically saved his life during the years of sentencing and persecution.

The one convicted with gangrenous feet was sent to the camp where convicts worked with their feet submerged in mud to drain the Maliqi marsh. His condition worsened, but with the invaluable help of doctor Isuf Hysenbegasi, his wounds healed. However, he was left deaf in his right ear and partially in his left due to electric shocks; he remained permanently injured, including his feet.

During the year he was tortured in interrogation, the Albanian government continued its reforms, which also affected Adem’s family. The Knitting Factory of his father-in-law, where his wife, Shadija, had also been engaged in the early years, was nationalized. Adem’s movable and immovable properties were seized as part of his punishment. All of this made life even more difficult for his wife, who was left alone with their two-year-old daughter, Zana.

Gangrene in his feet, gladiolus in his soul

In 1952, Adem Beli was conditionally released and sent, of course under surveillance, to work as a prisoner in Gjazë of Lushnja. From there, he was taken to the artisan prison in Tirana, to translate literature from Italian and French. During this time, yet again, one of those miraculous interventions occurred that granted the agronomist his freedom, whom the regime had decided to let rot in prison.

The director of the prison, Laze Sulejmani, from Vlora, who knew Adem from his work in Vlorë, was astonished when he saw him and promised that he would speak with the other Vlora native, Hysni Kapo, to get him out of there. Hysni Kapo, who knew of Adem’s contributions in France and later in the city of Vlorë, managed to secure his release from prison. From 1954 until his early retirement in 1971, Adem worked as an agronomist in various cooperatives in Shkodër, Lezhë, Krujë, and Tirana.

During these years, he implemented successful original methods, such as the combined fertilization method, for which accolades went to the chest of the cooperative’s chairman where he served. Although Adem managed to return to his profession, it was not meant for the shadow of persecution to leave him.

In 1957, he was appointed as a lecturer at the School of Agricultural Cooperative Cadres, but when the director found out who he was, he did everything possible to dismiss him. His family was also hit by the same unjust treatment, although they were fortunate not to be interned.

His wife, although an excellent former lyceum student and knowledgeable in several foreign languages, could be nothing more than a kindergarten teacher. His eldest daughter, Zana, despite graduating with high marks from the Pedagogical School, worked only in the villages until the fall of the communist regime. His sons, Lirimi and Arbeni, born after his release from prison, despite their intellectual abilities (Lirimi was an excellent student, as his brother emphasizes), could not continue their higher education like their peers, but were sent to work “where the homeland needed.” Just as Adem Beli had gone throughout his life.

Agronomist Adem Beli ended his career in the field of bulb flower cultivation, which contrasted with his condition in terms of beauty and colors. Adem’s life was entirely the opposite of a field of flowers. However, among them, there was one flower that matched the agronomist’s spirit: Gladiola, which symbolizes strength of character, integrity, honesty, and never giving up in most cultures. In 1996, two years before his death, Adem Beli was honored with the medal; “Torchbearer of Democracy.” Memorie.al