Part One

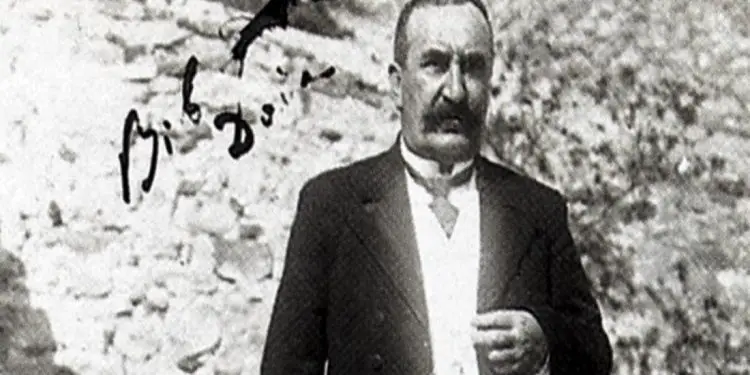

Memorie.al / To make known to the Great Powers the demands of the uprising of the Catholic tribes of Northern Albania, and subsequently to coordinate efforts with neighboring countries for the Albanian cause, the assembly entrusted Prend Doçi with the task. This was the first attempt with a genuine diplomatic emphasis which, although well-studied, unfortunately remained within the framework of an “impossible mission.” The journey of this mission began directly from the last assembly held in Breshtë of Orosh in early May of that year. With the goal of self-accrediting outside the territory of the Ottoman Empire and then traveling through Montenegro, Prend Doçi was to journey to Vienna, Rome, Paris, and London. Thirty-five years later, the “Old Man of Vlora” (Ismail Qemali) would follow the same itinerary and more or less with the same purpose.

The dream lasted briefly, indeed very briefly. Within a few days, everything was overturned. The Abbot was arrested within Ottoman territory in the village of Vuthaj, near Gucia. A coincidence? Or something else? No one knows the truth. The betrayal of this mission from its very start -which fundamentally changed the life of the parish priest of Kalivare – continues to provoke the minds of various researchers today. In a letter dated May 7, 1877, sent by Calonne Ceccaldi, the French Consul in Shkodra, to Duke Decazes, it is written among other things…!

“Abbot Don Primo and Kapedan Gjon Doda, a cousin of Preng Bib Doda, are heading through mountain paths to Cetinje to coordinate the Mirdita uprising with Montenegro.” Thus, the French Consulate in Shkodra was fully aware of Prend Doçi’s movements and perhaps evens his mission! Not only that, but from the way the consul communicates with his superior, the Foreign Minister (note the reference to “Abbot Don Primo”), it is clearly understood that Prend Doçi was a focus of silent French diplomacy as an uncontrollable instigator of anti-Ottoman resistance in Upper Albania.

Only a week later, this same diplomat, using entirely different language, would be the first to telegraphically inform the relevant department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding the arrest of Prend Doçi and his companions. For Abbot Doçi, the mission remained for many years a staggering vision full of unexpected events – as difficult and bitter as they were pleasant and hopeful – which kept him forever bound to his homeland.

The Arrest

Many Albanian and foreign authors have written about the arrest of Prend Doçi and the events that followed. While being both appreciative and selective in evaluating their contributions, I must declare from the outset that, for many reasons, I am inclined to lean toward the testimonies left to us by Father Pashk Bardhi and Dom Prend Suli. “His escape, capture, imprisonment, and conquest – I am writing them here exactly as he told me with his own mouth…” writes Father Pashk Bardhi.

As if knowing that descendants would encounter other variants, the author continues: “With purpose, I also asked the Right Reverend Dom Ndoc Nikaj, who was his intimate friend, and he confirmed that as he told me, so he told him. From this account, it appears that Monsignor Doçi was lucky in these circumstances, or, as our people say, he was a man with a ‘guardian spirit’ (njeri me orë). He always had his spirit awake.”

From another letter by Calonne Ceccaldi to Duke Decazes dated May 22, 1877, we learn that Prend Doçi and six of the organizers of the highlanders’ resistance of Gomsiqe – at the Pass of Guri i Prerë of Shën Pal – along with Kapedan Gjon Marku, were prisoners. After a 4-day stay in the Pristina prison, they were traveling to Istanbul. This implies their arrest occurred around May 16 or 17.

The first stop of the echelon escorting the prisoners was the military garrison prison near the port in Thessaloniki. This is confirmed by Prend Doçi’s own testimony relayed through his contemporary and close friend, Father Pashk Bardhi. Here, the author does not mention the men from Dukagjin whom Kapedan Gjon Doda intended to take with him to Montenegro. He also does not mention Kolë Marçuni, who was arrested along with the Abbot.

Nothing is known of his fate. He was older and enjoyed the Abbot’s trust. After being crammed into a tiny room, after 37 hours, they were brought a basin of broth and 4 spoons with which seven men had to quench the hunger and fatigue of a long journey with bound hands and feet. … “As soon as they ate that broth, a trumpet sounded, the prison door opened immediately, and a Turkish officer said in a faint voice: – Arnaut, out!”

In the large courtyard before the palace (saray), the thick morning mist weighed down the sea horizon ahead. The cool air seemed to ease their breathing and clear their vision. Along the wall that served perhaps as a barricade, they noticed a row of soldiers with weapons in hand. It seemed they were experiencing their final moments. “Hope in God, Father, for they are taking us to be slaughtered,” Kapedan Gjoni whispered. “Why not!” the Abbot replied cold-bloodedly.

“Except if the bullet hits me in the stomach, because to this day I have never eaten the Sultan’s (Daulet) goods. Except this bit of broth, and even this I want to leave here.” But the soldier (asqer) was about his own business and had nothing to do with them. They were put on a steamer and sent to Istanbul. On the steamer, according to Father Pashk Bardhi, they met Pashko Vasa, who had undertaken that journey specifically to meet them.

It is said he asked them why they hadn’t stood until death, because they would hardly escape the wrath of Dervish Pasha. According to Nopcsa, they resisted! After an extremely difficult journey, in the late hours of a pitch-black night with rain showers of a late spring, the steamer anchored at the pier in Istanbul. They were the last to leave the ship.

Unlike the other passengers, they did not step onto land, but into the dark belly of another ramshackle ship that looked more like a floating pen, which barely set sail under the weight of doubled guards toward the “Final Station.” This was the slang name for the prison of foreigners (non-Ottomans) built at the foot of a rock massif in a lonely gorge, not far from the port.

Life as a “Game of Chance”

The sudden arrest of Prend Doçi and his incognito transfer to Istanbul had a painful resonance not only among the Mirdita people but also among all the Catholic tribes of Upper Albania. The highest leaders of the church hierarchy immediately led the efforts to save Prend Doçi’s life.

The Bishop of the Diocese of Sapa, Giulio Marsili, and the superior of the Franciscans, in the name of all other members of the Catholic clergy, requested the French government through the French consul in Shkodra to intervene as soon as possible with the Sublime Porte to save Abbot Prend Doçi’s life.

Not only the consul’s personal stance but also the predisposition of the French government is clearly expressed in his letter No. 165 sent to Duke Decazes on May 22, 1877.

… “I did not hide from the petitioners that the way this priest – interesting both for his young age, wisdom, and patriotism – had involved himself in the Mirdita disturbances, made our intervention on his behalf quite difficult, especially since the French government, through my mediation, had not ceased warning Preng Doda and his supporters about the dangers they were putting themselves into…”

Not only that, but the French consul in Shkodra, as a keen observer and messenger of policy – in my opinion, an unkind one – goes even further, and with careful diplomatic language dares to advise his superior to act, if deemed necessary, without direct intervention, not crossing the appropriate boundary.

From a reply letter by the Archbishop of Tivar and Shkodra, Monsignor Karl Pooten, sent to Cardinal Alessandro Franchi on June 25, 1877, we learn that the Vicar of Constantinople, Mgr. Hassun, was also concerned about the fate of the parish priest of Kalivare.

In this letter, the balanced stance of the German Karl Pooten is striking. … “Unfortunately, he is a priest, a student of Propaganda Fide. The young Don Primo Doçi is well-educated but has misused his knowledge,” Pooten writes to the Cardinal. Meanwhile, Pooten asks Mgr. Hassun to intervene so that Prend Doçi would not be kept in the same prison as the other detainees and that his religious status be respected.

The only exception in this matter was the Bishop of Lezha, Monsignor Francesco Malcinski, who characterized Prend Doçi as the main organizer of the uprising, who went to the Prince of Montenegro in the capacity of a political agent.

Let us return to Istanbul. The prison had earned the nickname “Final Station” over the years because whoever entered rarely came out alive. Built on the steep face of a cliff that dropped sharply into the sea, from afar it looked like a trapezoidal truncated pyramid gradually sinking underwater. From a few oral testimonies of the Abbot himself, passed down by his Franciscan collaborators, it is learned that he endured a torturous interrogation.

… “The interrogation (istintaku) treated me worse than the prison…” the Abbot would say even years later, recalling that cold being with a smallpox-scarred face, equipped with a piercing and malicious gaze. He felt a visible scratch, a weight in his soul. It caused him a sliding contraction that made him fall silent with pain and regret because that investigator – the official who had squeezed him so hard – had, by a twist of fate, been an Albanian, a fellow countryman!

A distorted Arnaut to such an extent that when he failed to prove Preng Bib Doda’s guilt as the main organizer of the uprising through the Abbot’s depositions, he turned his back and cynically muttered in Albanian: “Paç veten në qafë!” (May your own blood be on your head).

Warning echoes of the next world. But God, for the sake of the land that birthed him, had reserved another fate. The Istanbul prison was of a unique kind, designed to suit the pathological hatred the Sublime Porte harbored for the disobedient non-Ottoman subjects across the Empire. A basement, whose contours could not easily be defined, floored with heavy stone slabs, divided lengthwise by a corridor of double iron bars. Armenians, Greeks, Romanians, Bulgarians, Vlachs, Hungarians, Moldavians, Albanians, etc., vented their souls’ rage through daily communication in their own languages. It was the early days of spring… the dampness to which the Abbot was unaccustomed had weighed heavily on his health. / Memorie.al