Memorie.al / The Year 1982: Blocks, walls, and curtains still standing. Albania, the almost impenetrable Marxist-Leninist fortress of Enver Hoxha. And those who managed to enter, under the eye of the State Security (Sigurimi), risked a great deal…! One cold Sunday morning in January 1982, I was sitting with my eyes closed on a bench by the sea in Lido di Camaiore, enjoying the pale rays of sunlight on my face, when I heard a half-forgotten voice calling me. I looked, but hardly recognized him. “Pasquale!” – I shouted – “What are you doing here?”

Pasquale was an old university acquaintance from Calabria who, at the time, had officially immigrated to Pisa to study (so to speak), but was a front-line activist of the Student Movement. He represented those who were then called “Katanga,” i.e., security personnel during strikes and demonstrations. A convinced Marxist-Leninist, he had tried unsuccessfully to persuade me to abandon my liberal ideals to join the utopian vision of the “sun of the future.” After my graduation, he had vanished into thin air.

And now, here he was again in front of me, telling me all his adventures up to his position as a representative of an Italian-Albanian cultural circle. From there, he found me three months later at the pier in Bari to board a Yugoslav ferry destined for the port of Bar in Montenegro; it was a series of strange, peculiar, and unusual situations desired by both of us. On one hand, Pasquale’s new attempt to bring me ideologically to his side, and on the other, my desire to experience a unique adventure, which indeed it was.

It must be said that, at that time, Albania was a country practically unknown to most people. Impenetrable. Closed borders, and with these airports and ports, there was no cooperation, no exchange, no possibility of telephone communication, except for that authorized and controlled by the regime. No one spoke about it, as if it didn’t exist. In books, the only information available dated back to the period between the Italian protectorate after World War I and the annexation that lasted from 1939 to 1944.

After that, absolute silence. A silence that coincided with forty-five years of Marxist-Leninist power, linked to the life of the country’s undisputed “leader”: Enver Hoxha. No updated road maps were available, except for fascist “reminders” from 1940.

During the overnight crossing, I got to know my travel companions better. “Comrades” in every sense: nine men and six women. Naturally, members of the cultural circle. Before departure, the order was: “Dress up, but no jeans or sneakers, because where we are going, they are considered too Western.” Women’s clothing had to be limited to skirts far below the knee, without heels or nylon stockings. Ultimately, this “dress code” was well specified in the instructions received before departure.

In Bar, a Yugoslav bus was waiting for us in the morning, tasked with taking us to the town of Vjeternik, a remote border point near Kosovo, about 300 km away. From there, we would have to reach Shkodra via inland roads for another 150 km. To better understand the situation at that time, just look at a simple road map today: the Bar-Shkodra road is only 50 km long. We traveled for 10 hours, including a two-hour stop at the border.

As soon as we reached the last Yugoslav post, the officer on duty asked us the reason for the visit to Albania (a mandatory emphasis on correct pronunciation). After Pasquale’s answer, with a sarcastic and not at all hidden smile, he said: “Happy Birthday.” He didn’t even want our passports. “The Albanians will think of it anyway,” he implied.

A good 500 meters separated the two borders. No man’s land – a dirt road with packed barriers here and there, channels to prevent acceleration for the few vehicles in transit (in two hours we saw none) – we crossed it on foot, dragging our luggage while a bothersome rain added to the discomfort. Then, finally, a large sign appeared, topped by a giant two-headed black eagle on a red background, announcing that we were entering the People’s Republic of Albania.

Of course, they were waiting for us. Greetings with a clenched fist, hot tea for everyone, military music, and the start of the luggage check. We quickly got the passports ready: they requested them and we only found them on the day of departure, with all the necessary stamps. We would have to return from there anyway: it was the only open gate in the whole city.

Suitcases and handbags were turned over one by one for a full inspection; “inspection” is an understatement. The six females “disappeared” for a search conducted by Albanian customs officers. We were checked in military style, meaning down to our underwear. All this with the constant repetition in Italian: “Na falni, na falni, na falni” (Forgive us). They sought out all newspapers, magazines, and clothing considered bourgeois. Special treatment was applied to cotton packs and hygienic towels: they were literally destroyed, thinking who knows what we might have hidden.

Finally, we boarded a new “Menarini” bus with 44 seats. Along with us, besides the driver, were three officials from the Party of Labour, two of whom performed supervisory duties, and one of a higher rank, representing the secret police, the Sigurimi. They all spoke Italian, even perfect Italian.

The journey to Shkodra was unbelievable. We continued to encounter reinforced concrete bunkers, half-hidden in the vegetation. We were told they were the people’s defense against sudden and inevitable invasion attempts by “Tito’s traitors,” supported by Italian and American imperialists, favored by the expansionist religious policy of the Vatican. “Welcome to Albania.”

Finally, we arrived at our destination. It was evening. A deserted city, few lights on. “After dinner, if you want to take a walk, it is allowed,” the Sigurimi agent told us. “And where are we going? Better to stay in the hotel,” was everyone’s thought. We stayed for two nights.

The first day was spent in Shkodra, a kind of model city in the vision of a communist society. Only public transport functioned, and the only allowed property was the bicycle; an atheist culture, the conversion of all places of worship (mosques, Catholic and Byzantine churches, synagogues) into Party of Labour offices, People’s Houses, or even worse, into gyms, such as the Catholic Cathedral. Nothing else was allowed to be seen: no lake, no Rozafa Castle. These visits were considered redundant in the logic of a journey dedicated mainly, or rather exclusively, to “cultural” meetings and exchanges.

The second day was dedicated to Kruja. I remember this city on a sunny spring day. It turned out to be a permitted visit because it was the birthplace of the only National Hero recognized as such even by the regime: Gjergj Kastrioti Skanderbeg. Living in the late middle Ages, he was the Albanian leader who fought the “Ottoman-Turkish oppressor.” The Castle overlooking the city, and then the National Museum of Resistance (against the Turks), was for us the only allowed tourist attraction.

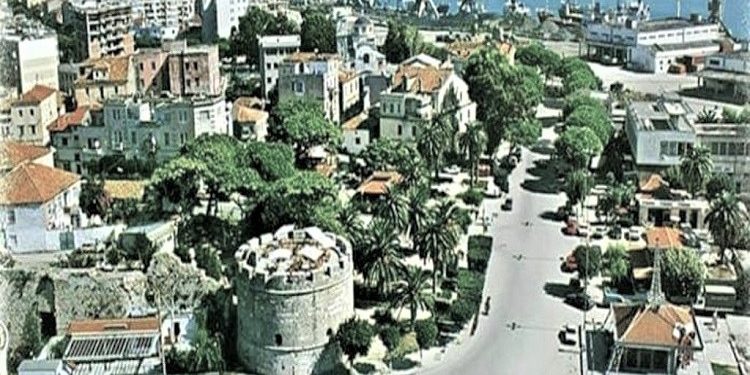

Then we went to Durrës. Hotel “Rex” by the sea, a fascist-style structure built in the late 1930s was our base for subsequent visits to the center-south of the country. Little remains in my memory of the city because we left early in the morning and returned late at night. But if monuments and museums are usually among the main reasons for a trip, in communist Albania, they did not think the same.

Attempts to visit the port, the Byzantine ruins dating between 600 and 800 AD, the Fatih Mosque dating back to the 16th century, the Roman amphitheater, or the Royal Villa built by King Zog I, were useless according to them.

“Why are you interested in visiting the building of the main leader of the Party of Labour, Enver Hoxha?” we were asked with no small surprise by two people who clearly appeared to be from the Secret Services. I apologized: I understood everything. And the fatal day came when I risked being kept in Albania as a suspicious person for spreading false news and praising American imperialist values.

We were traveling on the road from Shkodra to Durrës, which was also filled with bunkers to defend against attacks from the sea by the Italians. In the “Menarini” bus, the cassette player was transmitting the usual military marches sung by Albanian youth, when a soft, untouchable, sweet, and pleasant music, introduced by sopranos accompanied by oboe and harps, woke me from the torture. I caught my companions’ attention, shouting: “Guys, this is the music from Kismet” (an American musical known in Italy as “A Stranger Among Angels”) “by Bob Wright, sung by Vic Damone!”.

It was a serious mistake.

The Sigurimi agent stood up and threateningly reminded me: “What you are listening to is nothing other than the ‘Dance of the Maidens,’ taken from the Polovtsian Dances of the opera Prince Igor, by the Russian composer Alexander Borodin, recognized by his Albanian comrades as a pre-Marxist genius and activist. The Americans stole this melody and made it their own!”.

Military marches began to invade the bus again. Meanwhile, Pasquale discussed enthusiastically with the agent about the reason for my presence in the group, given my clear attitude, according to the Sigurimi representative, not suitable for the required Marxist-Leninist dictates. I avoid recounting what was said between me and Pasquale. In any case, I decided to give the mildest advice and the most measured interjections to avoid “unfortunate” consequences.

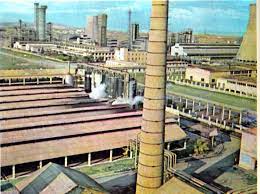

Elbasani required a detour of many kilometers just to visit a Metallurgical Combine, built thanks to the state aid of Chinese comrades. We were reminded that the alliance with Mao had now replaced the one with the Soviets: “revisionists and traitors.”

It is imperative to visit the giant emulation board at the factory entrance, with photos of distinguished workers who had exceeded the assigned work targets. Then came the inevitable meeting with a full delegation wearing red scarves around their necks, followed by a banquet in a large hall. We guests were placed at the table of the leading comrades, in the center of the room, on a stage. Military marches and speeches by “our brothers” echoed. Of course, it was Pasquale’s turn to thank them for their hospitality.

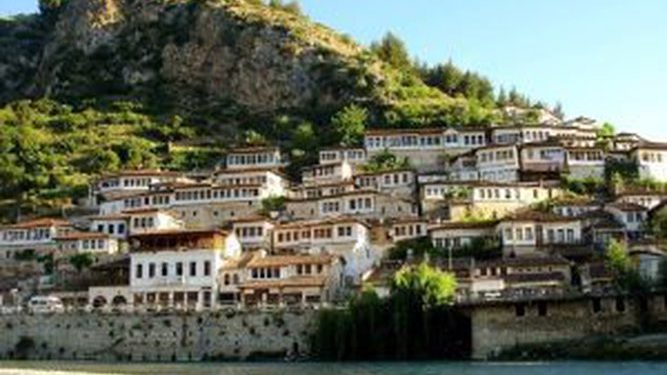

Berat was the city that made the entire trip to Albania worth it. A moment of discovery and charm, with characteristic buildings built with white walls and tile-colored plates. I still wonder how it managed to survive the harsh policy of renovation and reconstruction by the dictator Enver Hoxha, who destroyed all old buildings and then rebuilt new ones in the style of the regime. Perhaps even he was touched by such beauty?

An ancient Illyrian settlement, it later passed under Ottoman, Bulgarian, Serbian, and Turkish dominance. Two different religious souls are evident, one purely Christian and the other Muslim, the emblem of a peaceful cultural mix that has never been extinguished, with the Bachelors’ Mosque, the Ottoman King’s Mosque, the Lead Mosque, the small houses placed one above the other, which characterize the entire architecture of the area, the Church of Saint Spyridon, the small Church of Saint Thomas, and finally, the Berat Castle, an Ottoman fortress located on a hill overlooking the city.

From here, we enjoyed a wonderful view extending through the district of Berat, reaching in the distance to the green and wild environment. Breathtaking things. “As you see, our leader, the comrade commander, wanted to leave the cultural traditions of Albania to posterity, only and exclusively as memories and evidence of superiority, wars, and inequalities,” commented our guide. My travel companions nodded, while I finally breathed in some history and a real landscape.

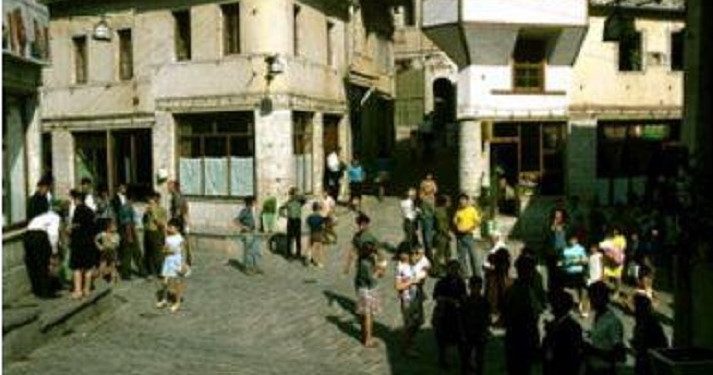

Finally, we arrived in Gjirokastra, a small city rooted in the mountains of Southern Albania; a wonderful historical city that would have received better attention from us if nearby “political and cultural” commitments had not prevented us from visiting it. Only the museum-house where “he” was born, the country’s “supreme force,” Enver Hoxha, was in fact the destination of our excursions. It is good that, being at the top of the city, to reach it on foot, one had to cross the whole city, through alleys, typical houses with stone roofs and walls of a “Hellenic” white.

As for the rest, we saw “nothing” – neither the Ottoman house of the Skenduli family, nor the city’s bazaar, nor a Turkish coffee. They didn’t even let us visit the Castle; it was taboo, also because it was used for holding political prisoners. The Bazaar Mosque was used as a training school for circus acrobats, as the height of the internal ceilings made it possible to comfortably hang trapezes.

We saw none of this because we had to return to Durrës (about 200 km away, estimated time 5 hours) to be punctual for the gala evening in the presence of high officials of the Party of Labour who had come especially for us from Tirana. The evening in which Pasquale exalted himself to the point of shouting: “I am coming to live here, in your republic, in the land of eagles, with my Albanian fellow citizens.”

With that event, the visit to Albania ended: Tirana remained outside the borders to be visited because the Youth Congress was taking place, they explained. The next day, we reached the border post where we had entered. We found everything that had been confiscated from us when we arrived; they were well-preserved. And they honored us each with a gift of the personal book of the main leader, Enver Hoxha: “The History of the Party of Labour of Albania” translated into Italian. A kind of “Mein Kampf” in a Marxist-Leninist version.

In Bari, we said goodbye. My travel companions, joyful and satisfied with their experience, sang the anthem of the Albanian workers, which they now knew by heart after countless joyful executions during the trips. Pasquale greeted me with a pat on the back, to remind me of three Stalin-style kisses. I never met him again./Memorie.al