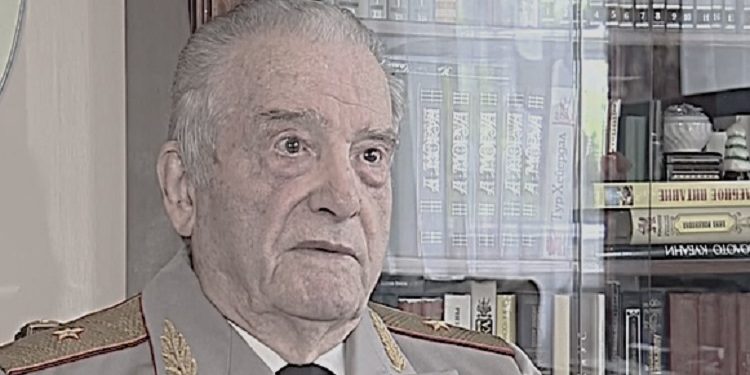

Memorie.al / On the anniversary of the liberation of Albania from Nazi occupiers, the television channel “Russia – 1” dedicated a short report to the Albanian partisan and general of the Soviet Army, Jani Kiço Lufi. He served in the ranks of the Albanian and Soviet armies for nearly half a century. Over 48 years of service, he witnessed a variety of events and happenings. He fought with a weapon in hand for the liberation of Albania from the Italian-German fascist occupiers. In the Soviet army, however, he climbed the military career ladder, from battalion commander to the position of corps chief of staff.

In 2003, his autobiographical book “From Albanian Partisan to Soviet General” was published in Russia, and then in 2008, it was translated into Albanian by Professor As. Dr. Gjergj P. Titani and researcher Robert S. Vullkani and republished in Tirana.

THE EVENT

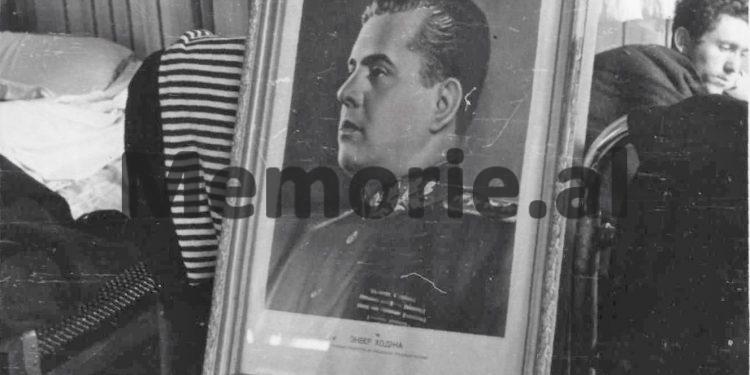

The orders signed by Enver Hoxha were categorical: Sever political, military, and economic relations with Moscow! All students from the Soviet Union must return! The response was immediate and without hesitation. The unexpected only happened with the “Frunze” student who dared to defy Tirana’s order.

Jani Lufi remained in Moscow and did not interrupt his studies. A furious rage would be unleashed against him. Officials would fill out special reports; “Jani Lufi was recruited by the KGB,” “He was swept away by the love of a general’s daughter,” “He was compromised with rubles and vodka.”

A host of versions of treason and espionage activities were condemned against him, so much so that Jani Lufi’s name took on the dimensions of a mysterious legend. This happened while he, the former partisan of “Thanas Ziko,” the communist from Sofratika, the senior officer of the “Skënderbej” academy, continued his life far from his family and close friends, unaware of what was being said about him.

Many years later, the “traitor” of the Tirana regime, who continued his military career in the former Soviet Union for decades, tries to clarify in an autobiographical book the circumstances under which he was forced to stay in the former Soviet Union when others returned without hesitation.

For him, the act long commented on over the years was neither a challenge nor treason. “When the order to return was communicated by the Albanian authorities,” Lufi states there, “I was far from Moscow, being treated in a regional hospital.”

More or less, some of his former “Frunze” comrades recently expressed the same in their memories of the unusual event. Contrary to this version, in the Albanian archives, where the file of “the betrayal of the military officer Jani Lufi” has been fanatically preserved, there is a document that illuminates, more or less, another course of events.

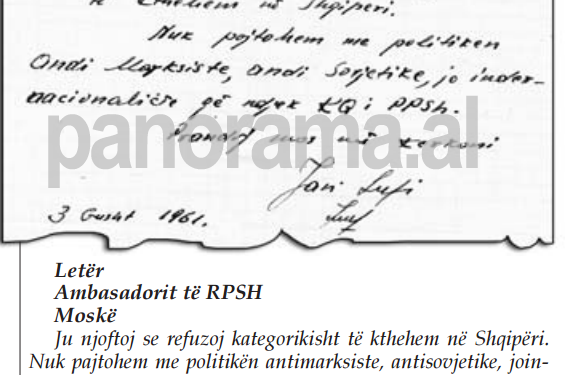

In a handwritten letter dated August 3, 1961, the “Frunze” academician notifies the Albanian Embassy in Moscow that he categorically refuses to return to Albania because he does not agree with the anti-Marxist, anti-Soviet, and non-internationalist policy pursued by the Central Committee of the Party of Labor of Albania.

THE AMBASSADOR’S LETTER

Subject: On the betrayal of former Party member, Jani Lufi

To the Central Committee of the Party

(Foreign Directorate)

On August 3, along with six other comrades who were continuing their studies at the “Frunze” Academy, Jani Lufi was also supposed to leave for Tirana, but, as is known, the aforementioned did not leave and committed treason.

To clarify the matter with the official bodies, comrade Dilaver Poçi was assigned, who met with the deputy commander of the said Academy and later with the Deputy Minister of Defense, General Gusiev.

From the meetings he had and the discussions held, it resulted that they, on purpose, did not tell the truth but tried with “good words” to make us passive. General Gusiev, in the last meeting with Dilaver, said that Jani Lufi had gone on vacation to the Black Sea without asking the school’s command, considered this a lack of discipline on Jani’s part, and other nonsense.

On August 10, comrade Nesti received a letter from Jani Lufi. In this letter, he writes that he has decided to stay in the Soviet Union because he does not agree with the “anti-Marxist,” “anti-Soviet,” and “non-international” line that, according to him, our Party is pursuing.

The letter was dated August 3, 1961. Jani Lufi was a First Captain and had finished the second year of his studies. He is a Greek minority member. It results that he does not have parents or his own family. We add that the Party organization had not been able to create any suspicion about his political stance.

For the Party Committee

Secretary

Petro Godeshi

General Jani Lufi’s Interview

“How I became a general in the Soviet Union, I, the Albanian partisan”

“Good evening, brothers! I’m Jani Lufi, speaking from Krasnodar.” Finally, from the other end of the phone, we hear the voice of the man we have been looking for for days. Eager to tell his story, the Albanian military officer who spent his life in distant Russia begins to speak in clear Albanian, interrupting himself from time to time with a few broken “da, da” (yes, yes).

Jani Lufi, unlike few others, has a unique life story, which he wishes to divide into two moments that naturally blend into one another. If the time and geographical factors have confronted him with specific circumstances, this has been insignificant for the character and essential values inherited from his homeland.

“I was Jani Lufi, the 14-year-old partisan of the ‘Thanas Ziko’ battalion. But I am also the general of the Soviet Army.” In his further account, the man answering in Albanian from distant Krasnodar says that life has reserved a strange fate for him, but he is proud that he has known how to maintain balance and remain high-headed in front of acquaintances and those with whom he shared a common profession and duty. However, not everything has flowed in a crescendo for him.

Spending half a century away from family, comrades, friends, and the people he grew up and was educated with, has been both exhausting and dramatic. “What’s more,” Jani Lufi adds, “the way my stay in Moscow was discussed in Albania after the divorce of the ’60s has distressed me immensely and made me age prematurely.” Disregarding the accusations against him, he tries to recall them with a laugh, at least as much as he learned from the versions raised by the State Security.

“They said a beautiful girl – the daughter of a general from Moscow – blinded me, while I got married ten years after the relations between the two countries broke down. They called me a KGB agent while I continued to hold my membership card for the Communist Party of Albania. They said I was recruited by foreign intelligence during the war, while I was a partisan and followed the occupier step-by-step in my country.”

More than providing a counter-argument, Jani Lufi tries to clarify the circumstances under which he made his respective choices, convinced that he owes it to the public, and especially to the comrades with whom he once shared the joys of common duties. The truth is that Tirana in those years consumed a flurry of accusations against the “Frunze” student who did not return home after the break with the Soviet Union. But what really happened to him?

In his exclusive account, Jani Lufi brings a retrospective of his life, starting from his childhood years in Sofratika of Gjirokastra, his partisan battles in the ranks of the “Thanas Ziko” battalion, his “Skanderbeg” days, his studies at the Military Academy, the period when he served as an officer in Tirana, his studies at “Frunze” in the former Soviet Union, and up to the moments of his promotion to general…!

General, first, tell us something about the key moments of your life…?

First, I want to say that I am Albanian, the son of two unfortunate parents from Southern Albania. I was born in the village of Sofratika in the Gjirokastra district. Sofratika is a beautiful village, surrounded by mountains and narrow gorges that end at the rushing rivers below its feet. I turned eight there, then I left and never returned…!

What do you remember about the house where you were born?

Our house was at the top of the village. A friend of mine who lives in Greece, Vangjel Nasto, and a niece of ours in Libohova, Sofija, recently wrote to me that its ruins are clearly visible even today, while the corners of the walls have not been completely flattened.

Do you remember any events from that period of life in Sofratika?

I remember the “kurbet” (labor migration), the drama that our villagers experienced at that time. I especially remember the songs of sorrow of the women for the men who took the road of migration for a better life. Every house was marked by its pains.

Newly married young men parted with their beautiful wives and small children and sought their fortune beyond the mountains, far away, in America, Australia, New Zealand, France, etc. Many of them never returned. Meanwhile, their mothers and wives spent their lives in this long wait, which often lasted as long as their own lives.

Something about your family…?

I’ll start with my mother, whose family roots were Albanian. She was from Qeparo of Himara. My grandfather owned a large number of sheep and goats, which he kept there in winter and brought to the hills of Libohova in summer. The ritual of this migration was the reason for his friendship with my father’s family, from which my parents’ friendship was born.

Thus, in the summer of 1930, Kiço Lufi married my mother, Teodora Kopali. From this marriage, on May 15, 1931, I was born, their only son. I loved my parents very much. It was their bad luck that they left this life young…!

In your village, in Sofratika, they spoke Greek, how difficult was it for your mother to integrate into its community?

My mother only knew Albanian, and this made communication with others extremely difficult for her. What’s more, she became a widow at a very young age after my father died in 1938 and she experienced his death very hard.

What do you remember from the period of school in the village?

It was the spring of ’39 when I started school. I remember that the premises of the village church were adapted for classrooms, and from March 1 to September 30, we had our lessons there. There were four classes in total. We only had one teacher at school. I have remembered his profile with special admiration my whole life. His name was Spiro Xhai.

He was a kind and educated man. During the war years, he became one of the well-known cadres of the Movement. Our school would only continue for a year, as in December it would be closed by the situation created by the occupation of the country by fascist Italy.

How did your generation experience the occupation of Albania by fascist Italy…?

It was April 9 when the vanguard of the Italian infantry expeditionary division’s units arrived in our village, Sofratika, and the guard units were deployed down in the field. From the very first contact, the Italian soldiers behaved terribly badly with the villagers.

Brutality and arrogance were the only language of their communication with the locals. Their shameless attitudes toward women and girls were particularly revolting. There were many clashes with them in the first days over the various provocations they made.

The only reaction was to protect women and girls from being exposed to these uninvited guests. Their boorishness was extraordinary and felt everywhere. Being unscrupulous as they were, they started their first attack on the many storks we had in the village.

They rushed like beasts and killed most of them. The rest fled, and since then until I left the village, the storks have not returned.

However, up to this point, their behavior, although shameful, at least did not endanger people’s lives. A threatening situation was created in Sofratika during the Italian army’s assault on the territories of Greece. Our village was on the border zone that separates Albania from Greece.

For the first time, the attack began on the morning of October 28, 1940. Then the whole area became a theater of war. On March 9, Greek forces broke the Italian assault. Subsequently, the withdrawal of troops and military arsenals began.

During the withdrawal, the Greek army made a big artillery strike against an Italian garrison that was located near Sofratika. Many Italian officers and soldiers were killed there. The next day they buried them on a hill above the village. Thus, Sofratika became the “monument” of World War II, of the Italian cemeteries…!

During the Greco-Italian war, did the state border with the southern neighbor melt away…?

The breaking of this border helped the Greeks to seek refuge and help on our land. In the autumn and winter of ’41-’42, Greece faced a real tragedy. The destructive war had left the country without food reserves. An extraordinary famine plagued the entire country. 320,000 people died from the bread crisis.

Hungry crowds of Greeks knocked on the doors of our houses every day and asked for a bite of bread just to survive. The truth is that our villagers responded with great humanism and at a time when they themselves were in a miserable state, they shared even the last bite with their neighbors… ! / Memorie.al