By Dr. Ledia Dushku

The third part

Memorie.al / The relations of totalitarian regimes with intellectuals have often become the subject of discussions in scholarly circles. It seems like when this relationship is delineated in two opposite directions, where the intellectual must choose between being a “man of the yard” or a “dissident”, without having a middle ground. But in communist dictatorships there is the concept of the “art of survival,” which is nothing more than a combination of calculated submission, self-controlled criticism, tactical keeping of a low profile, and the quietly intelligent use of opportunities that may arise. In this way, accepting the social contract of the communist regime does not always make the intellectual a “man of the court”.

Continues from the previous issue

Starting from the beginning of 1950, when the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the ALP and Enver Hoxha personally took full control of the Institute of Sciences, the formal connection of the Party organs with the only scientific institution in Albania was a concern for the leadership. For Enver Hoxha, the establishment of the Institute of Sciences was undoubtedly a success, but the Party had not created a fair view of the work there, “confusing it with the old framework that is there”!

“The Institute,” he continued, “has not been seen favorably, its work has been underestimated…, as there are old cadres, confidence in the work of the Institute has been lost, because there are more of them and why there only two or three party members, there”. In this context, Enver Hoxha considered it important to take two measures: first, “we must be careful that the Institute is not there to put the old cadres, but those who are there, we must try and we make them work”; secondly, “we must take care to prepare other cadres”, for which the experience of the “old cadres” should also be used.

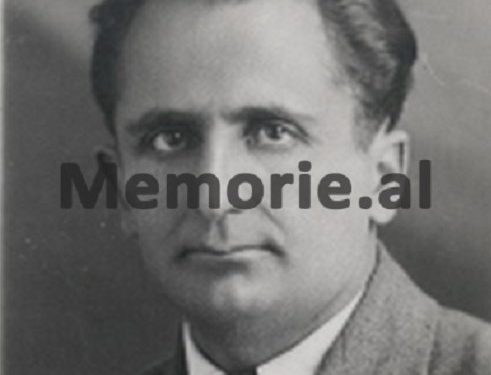

Since that meeting, the work at the Institute of Sciences would be placed under the Party’s microscope, and Hoxha would personally take over the reports and work plans there. So, he said: “That we need to know well, which are the cadres who work well there and this, not only with their names and biographies, but also with their capacity”! As an example, Eqrem Çabej himself was taken from him: “We know…what kind of element Eqrem Çabeu is, but we must try to make him work. The Central Committee must take these cadres and study them well, and it will be able to do this, if it knows well what is done there”.

Now, periodically almost every two years, when the work of the Institute of Sciences would be discussed in the leading bodies, Enver Hoxha would mention the name of researcher Çabej. He would thus be a representative of that category of the old, impartial elite, who “did not make an effort to embrace the Marxist-Leninist ideology”, whose work in the conditions of the lack of trained young researchers in the Soviet Union and countries of the People’s Democracies, would be considered important for the Communist Party and regime.

Since the very harsh behavior of the state with a part of the old elite, eliminated between 1946-1951, and the cleansing of the administration from “enemy elements”, in support of the decision of the Secretariat of the K.Q., of the APS, of February 14 1951, a softening of the relationship of the party / state, with the “old intellectuals”, considered “enemies”.

The fact of “breaking bridges” with them was a concern for the communist leadership. As long as the intellectual activity of this category was considered important, the Party’s work “with enemy intellectuals” had to be valued. Neglect was considered as “letting go”, while emphasis was placed on the fact that; “the enemy, on the other hand, works”. In this spirit, it was requested that intellectuals, party members, have more patience and fight sectarianism against the old elite, even not to underestimate their capacities. The new elite should not be afraid of the relationship with the old, because they were “armed with Marxism-Leninism and advanced Soviet science and culture”, and as such; “are more absolutely superior to intellectuals of the old school and with foreign ideology”.

This new approach, seemingly more tame, in the Party’s work with “old intellectuals”, was also reinforced by Enver Hoxha: “They should have a social spirit to help them move forward…! But this is not achieved in a police-like manner, with violence, with banging fists on the table, with restriction and suffocation of discussions, with methods of imposition and others of this nature. This means: this is the intellectual with his faults and with his advantages, removes the faults, help him for this and put him on the road”.

All of the above was also reflected in the attitude towards Eqrem Çabej. At the meeting of the Political Bureau of the K.Q., of the APS, on January 25, 1952, which examined the work of the Institute of Sciences, the discussion about “old cadres” was avoided. Even to Mehmet Shehu’s question: “Çabe and others should remain there”? Enver Hoxha did not answer, implying that there was no harshness towards them. In this aspect, Hoxha also overlooked the report of Misto Treska, responsible for the culture and arts section in the Agit-Prop Directorate in the K.Q., of the APS, in which Çabej was considered a man who neither politically nor ideologically was with the communists and what was worse, it could not even be educated and corrected.

The attitude towards him would change in 1954, when the number of “young cadres” prepared in BS and other countries of the East had increased, reducing the ratio of this category to that of “old cadres” in the Institute of Sciences . The new situation would be pointed out by Enver Hoxha himself, at the meeting of the Political Bureau of the Central Committee of the ALP, on February 24, 1954. According to him: “We have hundreds of cadres trained in the theory and high science of vanguard”. The moment had already come to put an end to the practice until then, when “we didn’t have senior cadres, when they were few, they were counted on the fingers, so this work for us was difficult”.

Enver Hoxha’s position regarding the old intellectuals, considered enemies, would be harsh: “Let’s end it once and for all, with those old elements that have nothing to do with our new science and power ours, but they are even enemies and they are allegedly kept there, because they are trained and knowledgeable. The knowledge of people like Sejfulla Malëshova, Eqrem Çabej, etc., is of no use to the Institute, which has great goals. We must give competence to the institute, so that those people don’t keep them anymore, because we have kept them enough and in those hands we cannot give our scientific secrets. Therefore we must purge those people… The Institute of Sciences… cannot keep in its bosom, people who stay there because they are supposedly old, mature or learned, when at one time, they are enemies of our people’s power, of new science and of socialism…”!

But the Party’s relationship with the researcher Çabej will take a different approach, starting from 1955. At the meeting of the Political Bureau, on March 3, 1955, when the new composition of the Institute of Sciences was discussed, in contrast to the year before, Enver Hoxha’s enthusiasm for increasing the number of researchers at the Institute of Sciences had declined. “We can’t give 40 people”, – he stated, as the needs were there. But the meeting reserved a surprise, regarding the attitude towards Eqrem Çabej, whose name was proposed by the Institute of Sciences, to be removed from its composition.

In order not to refute what Enver Hoxha himself had said about Çabej a year ago, another member of the family, Nexhmije Hoxha, director of the agitation and propaganda sector in the K.Q., of the ALP, took the word about him. . She said: “For Eqerem Çabeji, if we start from the political side, he can be removed, but I say that he should not be removed, considering that today [scientifically] he works for us, so this should be looked at”. Her word would seal everything and Çabej would continue to work at the Institute of Sciences.

The research work was thus the fourth aspect that conditioned the state’s relations with the researcher Çabej. Based on the characteristics of the “employee of the mind”, the state’s approach to him takes into account: the field of research and the quality of scientific work, this aspect that, in the final analysis, positively affected the state’s relationship with researcher Çabej; the work methodology, which in the case of Çabej, proved challenging in his relationship with the state. Despite attempts to impose Marxist ideology in his academic work, Çabej continued to write, relying on “bourgeois ideology” and the “German idealist school”. This second aspect, in the final analysis, although it negatively affected the state’s relationship with the researcher, in the case of Çabej, was tolerated because of his essential and quality work.

In the memorandum “On the establishment of a four-year university faculty for the study of Albanian language and literature in Tirana”, drawn up by a group of researchers and presented, on August 17, 1947, to the Albanian government by Dhimitër Shuteriqi, the lack of specialists in the field of social sciences was headline. The fact that language studies within the country had been quite limited, that few people were engaged in them, mostly those who had the luck to stay close to an Albanianologist, were evident as the reasons for such a situation. Eqrem Çabej was one of them, who in the memorandum was considered “the most affirmed cadre from a scientific and linguistic point of view”.62 Equal to him was Kostaq Cipo, followed by Aleksandër Xhuvani, appreciated for his extensive scientific and linguistic culture.

So far, the Minister of Education, Sejfulla Malëshova, had set the work milestones at the Institute of Studies/Sciences. The Dictionary of the Albanian Language, the History of Literature and the Grammar of the Albanian Language were the areas in which the work would be concentrated in the linguistics and literature sector. Three teams of researchers started work, among which Eqrem Çabej was also a part. Initially, he worked with Cipo and Xhuvani on the Orthography and Dictionary of the Albanian Language, work that was continuously evaluated as careful and qualified scientific and since 1950 he was engaged in the History of Albanian Literature. The work for the latter put him in direct relationship with the head of the project, Dhimitër Shuteriq, an early member of the party, at that time the head of the League of Writers.

The work on the drafting of the History of Albanian Literature began in February 1950, but it did not proceed at the expected pace.65 For this, Dh. Shuteriqi blamed the Institute of Sciences, which had prioritized the preparation of the Linguistic Atlas of Albanian, neglecting the work of transcribing the works of old writers, such as Buzuku and Budi, considered indispensable for the History of Albanian Literature. In the letter that Shuteriqi and Mark Ndoja sent to the president of the Institute of Sciences, Manol Konomi, they informed that Eqrem Çabej was “the only person among us who has been interested in the “Albanian Atlas”…”, who was reluctant to undertake to work with the old authors of Albanian literature. The work for the compilation of the Atlas was considered by the duo Shuteriqi-Ndoja as “utopian” and the reluctance “to study the old Albanian authors and the Albanian literature, is harmful not only because it hinders the compilation of the History of Albanian Literature, but soon it will it also influenced other important issues…”. In a commanding tone, Shuteriqi-Ndoja demanded that Çabej, Cipo and Xhuvani, “the most experienced scientists for language work”, immediately deal with “the study and transcription of the most important authors, without allowing anyone else to study the someone else the transcription”.66

This is where Çabej’s work for the transliteration and transcription of Gjon Buzuku’s Meshari, the oldest book in the Albanian language discovered to date, originated. The work with Meshar, considered by specialists in the field “like the work of a monk”, began in the summer of 1950 and ended in 1958. It turned out to be long, very difficult, but qualitative and scrupulous. In 1955, when Nexhmije Hoxha spoke about Çabej’s work, the professor was working precisely with Meshari e Buzuku. In this way, Meshari not only highlighted the necessity of Çabe’s work, but in a way became his savior.68

In the meantime, the work of the reserved and taciturn professor had become present to the Leadership also from the reports of the associates of the State Security. The reports of the collaborator with the pseudonym “Edija” stand out here, in which Çabej was described as the researcher “who works with the lexicon [lexicon] of old texts of the Albanian language, which he knows well, whose work the linguistics section of make good use of; a man who works hard…, who knows the entire theoretical side of Albanian, what has been said about it by the great linguists”, the only researcher valued by Aleksandër Xhuvani, “who never takes the work out of hand when it is not finished as it should”.69 Such descriptions, without overlooking here the position of the Leadership towards Çabej, would force Captain Nuri Çakërri to put the note in May 1955, in Çabej’s form file: “The value of Çabej from the point of view of the History of Linguistics is great. Today that we lack such cadres, I agree… that by appreciating his work, without sparing… work on removing the reactionary worldview… when it is the case for any scientific delegation in People’s Democracies… . always send it with the purpose of affirmation”.

CONCLUSIONS

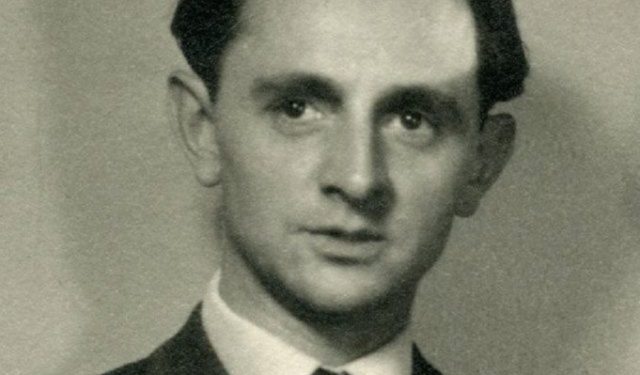

The 10-year period (1944-1954) turns out to be the most difficult for researcher Eqrem Çabej, both in human and professional terms. He resisted these years skillfully using work as the “art of survival”, without being either a “court man” intellectual or a “dissident” intellectual. The communist state pursued an iron fist policy towards him, surveilling him, closing him in and suppressing him in almost every aspect of his activity. Starting from 1955, the state’s relationship with him gradually began to take the form of the policy of the velvet glove, which was nothing but a very subtle form of violence and manipulation, with the aim of subjugation through coercion and coercion.

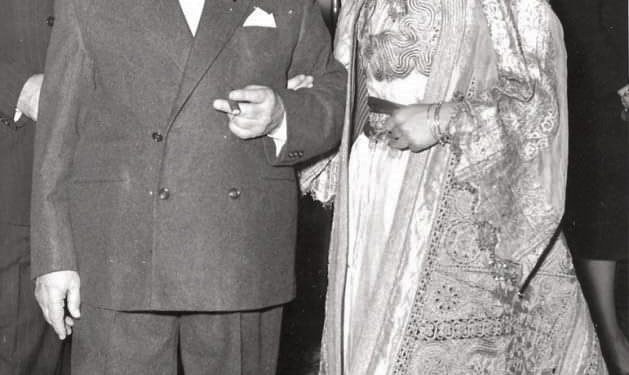

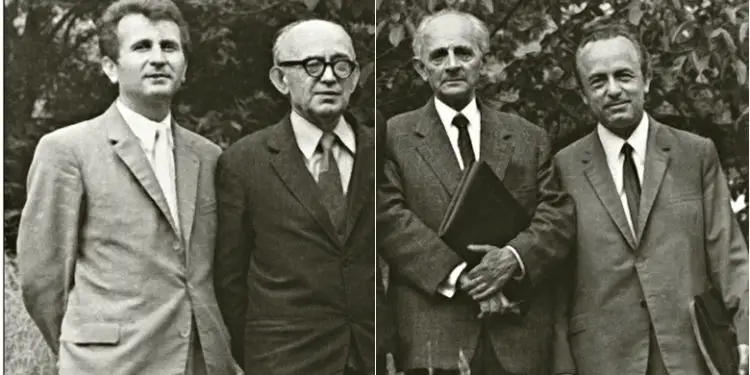

In this particular case, the “caress” begins and becomes visible since 1957, when Eqrem Çabej was awarded the Class II Order of Labor, to continue with several first prizes of the Republic and the awarding of the title “Teacher of the People” “. So, since 1961, Çabej would be part of the public discourse of Enver Hoxha, being considered as an “old friend” and “professor with excellent results”. Subsequently, from August 1963, with occasional ups and downs, he became part of the delegations of Albanian researchers abroad. The regime had thus begun to project the use of the unparalleled work of the language professor as its mirror in the international arena.

Meanwhile, away from the eyes of the public, the other side of the iron hand of Albanian totalitarianism was developing. It bears the name Form File, number 2383, which existed as such until five months after the death of Professor Çabej. Inside its 205 pages, one discovers the “other” of Çabej, the researcher, that of Çabej, the “enemy of popular power”, who did not embrace Marxism-Leninism, with a brother killed by the communists and a brother-in-law exponent of the National Front, who fled to America. These last two aspects, part of his family history in the years of the Second World War, throughout his life were alarm bells, hammers over his head, to frighten and convince him at the same time, wanting to remind him that for the regime he was “the beloved enemy”. Memorie.al