By Nafi Çegrani

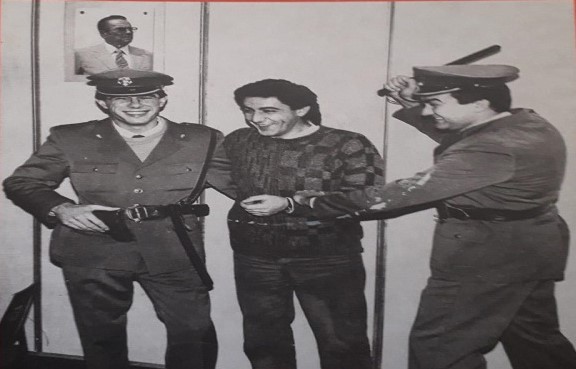

Memorie.al / Zenica Prison were not just a penal institution; it was a dark universe where a person lost their face, name, and dignity. In 1981, still young and with big dreams, I suddenly found myself cut off from the free world and seized by a merciless system. The handcuffs tightened to the bone, the damp and gloomy cell allowed no ray of light, while the silence of the thick walls made my nights long and unbearable. What hurt me the most was not the physical pain, nor the cold iron of the shackles, but the fact that I didn’t know why I was there? My conscience was clear as a tear. I had committed no crime, I had broken no law, I had nothing to hide.

Yet, I was treated as an enemy, as a predetermined culprit. This shook me deeply: it made me realize that a totalitarian system does not need evidence; it is enough for someone to be Albanian, to have a different opinion, or simply not to be submissive. In those moments, I began to see the prison not just as a physical space, but as a metaphor for a time and a world where justice had fallen from its throne.

One morning, the heavy iron door opened, and the guard entered the cell with an official document in his hands. It was the ruling (act-vendimi) of the investigating judge, Nikica Budul, which stated: “Pre-trial detention is extended for another 30 days.” The words were dry, bureaucratic, and lacked any clear justification. Instead of shedding light on the truth, they served only as a legal curtain to cover up arbitrariness.

According to every norm of justice, such a decision should contain evidence, arguments, and testimony. Instead, it was a form stripped of content, a cold seal that pushed my suffering further. I knew this was not a simple judicial error, but part of a premeditated mechanism: the Yugoslav UDBA and the chauvinist apparatus had leveled a fabricated charge against me, based on false testimony, slander, and shameful intrigues.

The judges, instead of protecting the law and the individual, had turned into notaries of a repressive system. They signed decisions prepared elsewhere, in the offices of the secret services, turning justice into a farce. And I, an innocent young man, was bearing the brunt of all this.

I did not want to remain silent. I asked the guard for a blank sheet of paper. In a corner of the cell, I began to write my complaint (ankesën) against Judge Budul’s decision. I was not a lawyer, but as a human being, I felt obligated to raise my voice. My words were simple, yet loaded with pain and dignity:

I denounced the inhumane behavior of the investigators. I pointed out the lack of concrete evidence. I demanded respect for the principle of the presumption of innocence. I spoke about the moral responsibility a judge has over a person’s fate.

I wrote it with the modest hope that someone, perhaps a judge with a conscience, would read it and pause to think. But the answer came quickly, cold, and absolute: “The request is baseless. The investigating judge’s decision is legal.”

With a dry sentence, containing no argument whatsoever, every window of hope was closed to me. I realized that the law did not exist to protect the innocent, but to subjugate them. It was a heavy moment, but also a moment of clarity: true justice could not be found in the courtrooms, but in my own conscience.

Grave Violation of Human Rights

From a legal standpoint, my detention in Zenica was a clear example of the violation of every legal norm, both national and international. The then-Yugoslav Constitution, in its articles, guaranteed the right to due process and the protection of human dignity.

The European Convention on Human Rights, which Yugoslavia had ratified, clearly sanctioned that no one could be detained without clear evidence and without a fair trial within a reasonable time.

Yet, in practice, these norms held no value. The investigators and judges, instead of being defenders of the law, acted as extensions of the UDBA. They did not judge based on evidence, but on political order. False witnesses, fabricated process-verbals (minutes), premeditated indictments – these were the tools used to manufacture the “guilt” of the innocent.

In my case, the fundamental elements of a procedure were completely missing: I did not have an independent defender, I was not informed of the supposed evidence against me, and I was not questioned in the presence of a lawyer. Everything was predetermined. Judge Budul’s decision was not a legal act, but a mechanical seal of a repressive machine.

The Degradation of the Human Being

In Zenica, a person was not just imprisoned physically; they were stripped of their dignity. The guards looked at you with scornful eyes, as if there was no human being before them, but just a number attached to a file. A smile, a plea, a simple question – everything was seen as a provocation.

The conditions were humiliating: damp cells, filthy bedding, scarce and often spoiled food. A glass of warm water could be considered a privilege. The hours of airing in the courtyard were rare, while sudden beatings from the guards were a daily part of “discipline”!

But the greatest humiliation was neither the stale bread nor the coldness of the walls. It was the way they treated you as unworthy of respect, as invisible. They killed every human sensation to make you feel like a nobody. And yet, in silence, every prisoner preserved within themselves a fragment of pride, a core of dignity that did not surrender.

I found this strength in my pure conscience. They could seize my freedom, but they could not seize my conviction that I had done nothing wrong. And this kept me alive.

The Unseen Wounds of the Soul

If the wounds of the body heal, the wounds of the soul remain. Imprisonment without guilt was a double psychological torture: the body suffers, but the soul is shattered. In Zenica, this torture took many forms:

- Prolonged isolation: Weeks without communication with anyone, except the voices of the guards.

- Constant threats: “We will destroy your family, you will rot in here.”

- Continuous humiliation: Insults, mockery, pushing, public contempt.

- Endless insecurity: No one would tell you how long the detention would last, what would happen tomorrow, what plan the system had for you.

These were wounds that were not seen, but they left deep traces. Many prisoners broke from within, gave up, and signed statements they didn’t believe in, just to gain a moment of relief.

But I decided not to be broken. My resistance was not external heroism, but an internal battle: not to accept the lie as truth, not to accept injustice as “normality.” This was my only weapon, my spiritual shield.

Justice as the Substance of Human Life

In Zenica Prison, between the damp walls and the cold bars, I began to understand something I had not fully conceived before: that justice is not merely a legal category, but the very substance of human life. Without justice, a person is not simply unprotected; they are stripped of their very being.

Ancient philosophers, from Plato to Aristotle, saw justice as the foundation of the city and the soul. Kant called it “the condition of perpetual peace,” while Camus said that the rebellion against injustice is the very proof of human dignity.

In my cell, these were no longer distant sayings, but a living reality: every day I had to choose whether to remain faithful to my truth, or to surrender to violence.

Freedom, in this context, was no longer the missing physical space, but an internal dimension. Where the law had fallen into the hands of chauvinism, where the courts had turned into a theater of shame, the only freedom left to me was the freedom of conscience. And this freedom, however fragile, was unbreakable.

Totalitarian Practices: Zenica Prison as the Gulag

What happened in Zenica was not accidental. It was part of a broader logic of totalitarian regimes, which used the prison not to rehabilitate the guilty, but to destroy the innocent.

In the Soviet Union, millions of people were sent to the Gulag with absurd charges, with fabricated indictments, with trials that were a parody. In Nazi Germany, the law was used to legitimize the Holocaust and the extermination of other peoples.

In Communist Albania, prisons and internment camps were filled with intellectuals, clerics, and patriots, who were declared “enemies of the people,” simply because they would not bow their heads.

Zenica was the Yugoslav link in this chain. All these systems shared a terrifying similarity: the law was no longer the protector of man, but a weapon against him. The judge did not judge, but signed; the investigator did not seek the truth, but produced guilt; the prison served not for justice, but for intimidation and subjugation.

These comparisons made me realize that my suffering was not only personal. It was part of a universal history of injustice, where the individual becomes a victim for the survival of power.

A Call for Today’s Generations

Many years later, when my mind returns to those dark days, I realize that the narration is not merely a personal recollection. It is a call to the generations of today. Because injustice, however distant it may seem, always finds new ways to return.

The new generation must learn that freedom and justice are not gifts, but a responsibility that must be defended every day. The law, to be true, must be above politics and above hatred. Judges and jurists must not be servants of power, but defenders of the individual.

My message is simple: remember Zenica, remember the Gulag, remember Spaç. Remember every cell where a person was imprisoned for free speech. Because memory is the strongest shield against the repetition of evil.

And for years and years, I have fought the battle in search of the truth, against the malicious acts of those who should dispense justice and speak with reason and logic before bringing cruel decisions and creating tragic human fates!

Just like those judges of the Yugoslav communist system, with their careerism and cynicism and their evil spirit, whose rulings were woven with such perfidious intrigue and mastery by the specialists of the criminal underground of the chauvinist and anti-Albanian regime, and which relate to the fate of a person and their vital interests, or those of a people or a nation…! / Memorie.al