From Valeria Dedaj

Memorie.al / Her love for Albania and her longing for friends and colleagues never wavers. Her return to Tirana to perform again at the University of Arts, alongside soprano Tatjana Korra, further demonstrated her desire to be close to the Albanian public. This concerns pianist Hermira Gjoni, who has lived in the United States for 25 years. In an exclusive interview with us, the Albanian pianist reflects on the most special moments of her career, as well as the difficulties she faced due to class struggle during the communist regime.

The mere fact that she was the granddaughter of Rauf Fico caused her to suffer during the 15 most beautiful years of her life, while working at the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet, putting her name on one of the blacklists, of the 30 artists who would be arrested and executed in the event of revolts against the communist power.

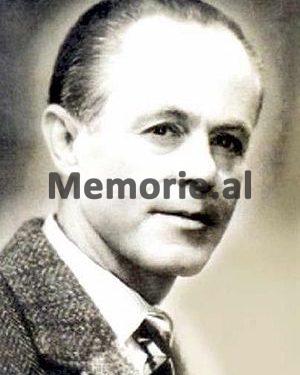

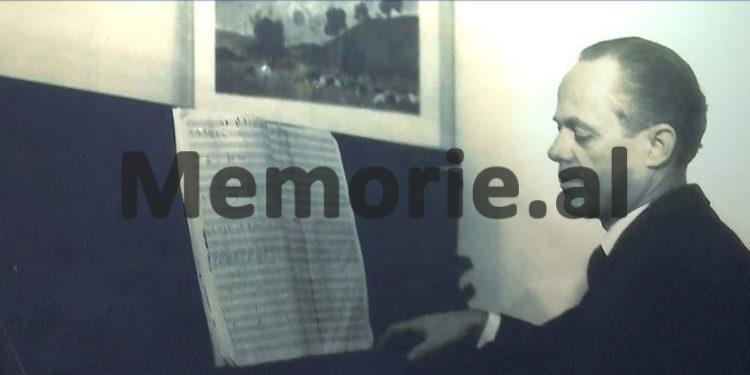

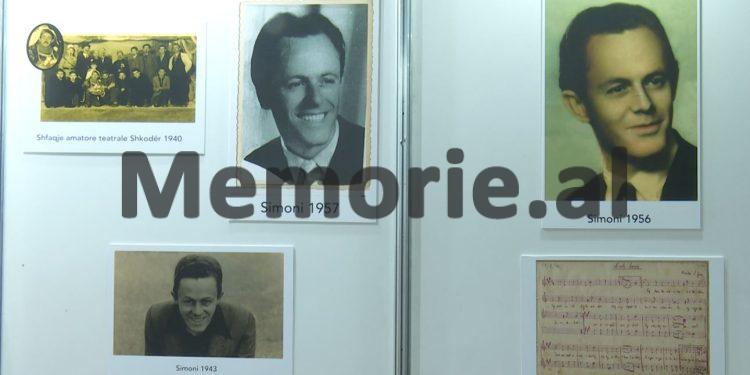

Although her uncle had left her when she was only four years old, the persecution of the communist regime never ceased, to the point that it did not even allow her husband, the renowned composer and conductor Simon Gjoni, to receive the recognition he deserved.

Mrs. Gjoni, let’s go back a bit to your childhood. How did your desire to pursue music come about?

In fact, it was my parents who advised me to follow the path of music. I was also helped a lot by my work with Professor Tonin Guraziu, with whom I studied at the Lyceum. Immediately after this period, I was appointed to the Opera and Ballet Theatre. Later, the State Conservatory of Tirana was opened (the Higher Institute of Arts), I interrupted my work and started my studies there. After graduating in 1966, I immediately began working as concertmaster at TKOB.

Those were wonderful years. It was a job done with a lot of passion, because there were amazing artists. I worked with works, whether they were Albanian, like Zoraqi’s, Zadeja’s, etc., but I also worked with classical operas like “The Barber of Seville,” “Butterfly,” etc., during which time I gave many concerts.

In the opera, you also met composer Simon Gjoni, who would later become your life partner…?

That’s when I met Simon. We worked together on “Don Pasquale,” “Butterfly,” “The Barber of Seville,” etc. That’s where our collaboration began. Music is something that connects you deeply; the communication through it is wonderful. He was a composer, and I performed his works, just like many other composers.

Did you ever think that one day he would become your husband?

No! Almost a year later, it happened spontaneously. Everything came naturally.

During that period, did you often represent Albania abroad?

Art has no limits. When you give a concert, you work to achieve even more. I represented Albania in many concerts abroad, with Gaqo Çako, I was with Mentor Xhemali when he received the gold medal (in a concert with him), but we were also abroad with Zoica Haxho, Agron Alia, etc. But then things changed.

Just because you were the granddaughter of Rauf Fico, the rhythms of this creation would change in 1975…?

These are things that have happened in art. It didn’t happen just to me. They used the fact that I was Rauf Fico’s granddaughter as a pretext, even though he had died when I was four years old.

Did they tell you the decision they had made?

No, never. Decisions were made back then without saying anything.

Why do you think this could have been the only reason?

Of course, that was it; there is nothing else. A class struggle was made to prevent me from performing in concerts, but it was also professional. People with little talent and professional ambition started to fight in such ways.

So you spent 15 years performing behind the scenes at TKOB?

Yes. However, for me, the best advisors were the great composers. Living with their works, living with art was a very good thing. You had the opportunity to talk with the geniuses of world music. It was much more beautiful this way than to spend your life with gossip.

Therefore, even though my past creativity was interrupted, I continued to remain silent, to study, and to have patience. I maintained my piano repertoire, and I had my position in the artistic game.

Your name, according to archival documents of the former State Security, which have recently emerged, was listed among the 30 most at-risk names for execution?

Yes, but I did not understand that. I found out very late, while I was in America.

What did you think when you learned this?

I said: “Why me, who has never been involved in these matters, who has never asked for anything, neither badges nor titles”? But when you work in art, you are also passionate about art. For example, there are “People’s Artists” here who have not sung a single song for the people, while Simoni, who was not a “People’s Artist,” was sung all the songs, so these did not matter to a true artist.

To be honest, my activity was interrupted, but when you are young, you go through these things with a smile. However, when your inner vision becomes more acute, you realize that your best years are slipping away and you are not doing what you were capable of doing, what you dreamed of. Then it became a great pain because they took away your rights.

The discussion about opening the files still continues… back then, this was not possible, but even now, the truths are told partially. Would you have liked to have learned the truth about that period?

Not then, because if I had known those truths, I would have been scared, walking on mines.

Has this situation affected the appreciation of Professor Gjoni?

Of course, he remained unappreciated. He didn’t just compose one song, but he wrote over three hundred songs. I have gathered a good portion of them, organizing them by different genres, but he also wrote many symphonic poems, an album for piano, an album of romances, an album of folk songs, etc. But with all this great activity he had, everything passed in silence.

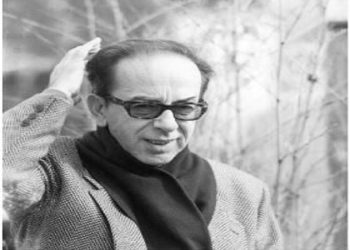

In 1991, Professor Gjoni passed away, but did he have any regrets?

He was a man with a big heart and family-oriented; he loved people very much. He spent his time either at home composing or with his children, but after giving two hours of lessons, he had a massive heart attack, as the doctors explained. His death was sudden because in his life, he had been very healthy; he never took an aspirin and never said: “I have a headache.”

It hit us like a bomb, however, ten days after Simon, Nikolla Zoraqi died, followed by Tonin Arapi, Pjetër Gaci, Çesk Zadeja, and the very last was Tish Daija.

Afterward, you left Albania…

I left in 1993. It was a lottery that I didn’t know existed, but a friend of mine in Boston threw it for me. After I learned how I had won, I thought to go once and then return again.

However, during this time, I sent my CV to 9 Music Conservatories. I received responses from some of them, one of which was a very good conservatory, and that’s where I went. As soon as they heard me play the piano, they asked me for nothing else.

Was it a second beginning for you?

Certainly, but there you go into a different system. The stress of adjustment is very great, but I didn’t say “no” to doing concerts, and thus, one concert led to another. I even remember that when I went to New York, I was valued so much that sometimes I felt not just underappreciated but overappreciated!

I thought: “What have I done here?”! When back in my country, I worked 11 hours a day and didn’t hear a single kind word! But I couldn’t look back, because I would hit a wall. I had to look ahead; only then could I give my best.

America teaches you to work, for you will be valued for what you do, but also to give up on others’ opinions. A person can face setbacks and failures in life, but they must reach their own goals. If I were to respond to all those who were failed musicians, I would waste my time.

What ties you to Albania?

It is the nostalgia of the past years; it’s not just about relatives, but also friends and colleagues. I gain strength when I come here, and when I leave, I begin my work more easily.

Biography

Hermira Gjoni took her first piano lessons at the age of 7 from Professor Tonin Guraziu. After finishing her studies at the State Conservatory of Tirana, she began working at the Theatre of Opera and Ballet as a concertmaster for 25 years. In 1959, she met her husband, the renowned composer Simon Gjoni, while working at the National Theatre of Opera and Ballet.

Hermira had the opportunity to work with four generations of singers, with whom she interpreted many arias, such as “Malatest” from the opera “Don Pasquale” by Donizetti, with Mihal Cenka, or the aria of “Juliet” from the opera “The Montagues and Capulets.” Her artistic activity, in 1975, was curtailed due to the class struggle. In 1990, she emigrated abroad, where she continued to perform at concerts. She currently lives in America. Memorie.al