Prof. Dr. Albert Frashëri

Part Two

Memorie.al / Understanding our time are impossible without an awareness of the “Absolute Evil” of the twentieth century. Western nations and the world of culture, immediately after World War II, sought to understand and condemn the ideology of Nazi-fascism. They were conscious of the dangers that ideology could pose to the future of democracy. Works of art, literature, and many profound studies were supported by society without neglecting historical truth. In this great undertaking, all fields of culture were engaged, not only from the right but also from the left.

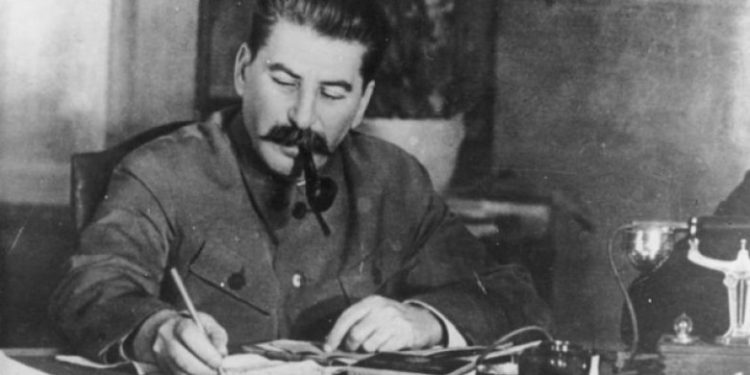

The fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989 became a symbol of the undignified agony of a system that swept nearly half of the European nations into its vortex. That system, rooted in communist ideology, blindly followed the lifeless shadow of Stalin. A significant portion of the intellectuals in the European cultural universe – and to a considerable extent, the political class of Western countries – had been infected by Marxist-leftist ideas.

Continued from the previous issue

There has not been a cultural movement, or a genuine commitment from the political class and society, to analyze and condemn left-wing totalitarianism in the same way they did, and continue to do, for right-wing totalitarianism. The leaders of Eastern European regimes committed monstrous and still unconfessed crimes, yet in none of those countries were the perpetrators subjected to judicial processes as prescribed by constitutional principles and the rule of law.

Could this underestimation of the problem be an accidental oversight? We are dealing with an unacceptable asymmetry compared to the processes organized by the winners of WWII against the criminals of right-wing regimes. Immediately after the war, the victors – Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and the USA – created a special tribunal at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg. The trial took place in two phases: the first act against 24 major war criminals, and the second act consisting of 12 secondary trials for lower-ranking war criminals.

After the collapse of totalitarian regimes, the leadership of the democratization process in Eastern European countries was generally taken by former communists: Yeltsin and Putin in Russia, Beria and Iliescu in Romania, the officials of Tito and Milošević in Yugoslavia, etc. They did not raise the issue of the right to judge the crimes of a long period. On the other hand, the indifference of Western democracies in this matter is inexcusable. A certain officer, molded in the ranks of the Russian secret services, is placed at the head of the country’s democratization and commands the most armed military on our planet. This is absurd and exceedingly dangerous, as time is proving beyond doubt.

And what can we say about these forms of totalitarianism that today’s youth do not know well enough? Is it possible to hide or coddle one totalitarianism in the shadow of another?

It is conscience that drives me to recount the absurdity of a reality that should not be dismissed as a mere curiosity or a wonder of the past. I believe there is little effort to meditate on the civilization of our time, the misguided trends, and the blatant injustices, or the absence of far-sighted leaders on the global stage. Is it possible to ignore, for instance, certain piquant events of our days? What can we say about a dangerous Eastern dictator who dreams of reviving past empires, rattling his sword left and right? Or about a former president of a Western democracy who hails as a “genius” the adventurer who wishes to become an emperor?

Today, amid a continuous crisis – not only economic – citizen’s risk returning to the illusions that, a century ago, brought about two deviant forms of power: the two totalitarianisms that caused tragedy and the temporary triumph of Absolute Evil.

Should we consider the risk of the return of dictatorships to the helm of important states? Is their revival possible?

The Western world condemned right-wing totalitarianism and analyzed many of its facets. However, unfortunately, there are not a few European citizens who express doubts about the real facts of violence and human suffering before and during the war. In the case of left-wing totalitarianisms, the danger is much greater. The indifference of society enables the revival of the childish ideal of absolute equality. In most Eastern countries, the democratization process was led by fanatical former communists.

Today, the prevalence of “sugary” literature nearly everywhere in the world has betrayed the critical spirit of art in Western countries. I am referring to so-called critical realism, in which the noblest expressions of democracy are constructed. I believe the sugary novel of our time resembles opium that fades the citizen’s awareness and distances them from the genuine problems of society.

Right-wing totalitarianism in Western Europe reigned for 12 to 20 years. Left-wing totalitarianism, conversely, suffocated the peoples of the East for a much longer time: from 45 to 72 years. The difference? People born and living under the shadow and censorship of the left were formed by and adapted to the dogmas of ideologies that are reviving today and threatening the world. The idea of absolute equality easily penetrates human consciousness, and this is dangerous because it goes against the natural principle of merit.

The West has not shown care in deeply analyzing and recognizing left-wing totalitarian regimes: historical analyses and, especially, artistic and literary works should orient the new generation toward a fundamental understanding of them. Today, whenever a country undergoes a difficult period, nostalgias for a past unknown to the youth are revived. These nostalgias are more dangerous today than ever.

What more can I say? I would like to offer the reader a fragment from the many truths I knew and lived in my youth, when as students after exams, we were sent to mandatory “voluntary work” for a month or two. That experience helped us understand real life: the one we lived, and not the one we had dreamed of.

Fragment from the novel “L’amara favola albanese” (The Bitter Albanian Fable)

By Alberto Frashëri, Roma, 2000

“…One afternoon, before sunset, with Pirro, Seit, Ahim, and two other friends, we went to see the monastery at the top of the hill near the camp. The path through the cypresses seemed desolate. The high walls of the monastery were covered in climbing plants. A lizard would occasionally hide from the sound of our footsteps, darting into narrow spaces between stones and, with hesitation or fear, keeping its head slightly out to hear the choir of cicadas.

The noise of the construction site could no longer be heard. One of the friends asked to stop for a cigarette. It was Mark, a student from a northern city. We sat under the branches of a tree near the main gate of the monastery, which was now sealed with wax. Mark offered us some of his tobacco.

‘It is Shkodër tobacco,’ he said. He repeated this every time he offered it.

He had told me about his family’s difficulties. They lived and worked in the village. They could not keep more than two pigs, he had told me some time ago. The agricultural cooperative’s regulations forbade it. Their time had to be dedicated to collective work in the cooperative’s fields. The government thought only of wheat and corn because that was the daily bread. For other things, they said, we shall see in the future. For the vital needs of the villagers, the cooperative fields were of little importance. They worked from morning to night. The pay they received was not enough even for daily bread; thus, they had to keep livestock – sheep or pigs – to feed the family and for a drop of milk for the infants.

Usually, Mark listened to others and spoke little. Everyone loved and respected him. Tall and boney, he seemed to be our epicenter. He perceived everything spoken among us in his own way, reflected, and then listened again. He seemed ten years older than us. He wore a long jacket, the same one since we met him four years prior. ‘He looks like a deserter,’ one of the girls in our class had said.

One day, he told me about the cooperative assembly, where the party secretary had announced a new directive: a cooperative family could keep at most two pigs and absolutely no more.

It was the idea of ‘bread at all costs.’ Their region, almost entirely Catholic, considered pig-rearing a primary issue. But, Mark told me, this was not a problem for them. Every family had created a hidden corner where they kept ‘outlaw’ pigs. Thus, they were pigs that did not recognize the Party’s law and grew in the darkness of a secret cage.

I had seen a film about the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. They called it Prohibition. With us, on the contrary, there was a prohibition against pigs, sheep, and cows. They ‘damaged the common interest.’ Sheep, pigs, and cows were condemned to live in illegality, hidden wherever possible, day and night, staying silent without raising their voices.

We were sitting under the branches of a larch, a few meters from Mark. He, leaning against the monastery gate, continued to smoke that hand-rolled cigarette he never let go of. A lizard, between two stones in the wall, appeared as if leaning on Mark’s shoulder. He didn’t notice and continued to listen – perhaps to the choir of cicadas. He wasn’t following our conversation. His gaze was lost in the distance, over the sea, which was almost invisible due to a light mist suffocating the horizon.

‘Mark, come join us,’ I said.

Mark stood up and, without a word, sat near us.

‘You didn’t ask how I found my family!’

His words did not sound like a reproach. The others looked at him somewhat surprised.

‘I found the family well, but not the pigs,’ he spoke, lighting another cigarette.

The choir of the cicadas was no longer heard. The lizard, curious about Mark’s words, emerged more prominently on his shoulder, enjoying the stillness and the cool evening air.

‘Do you want to know the news from my region?’

Only silence. No answer.

‘The Party discovered a hidden place where they were raising illegal pigs and took them from the families. There were only two illegal pigs. They seized them.’

Our friend was a man of few words. He spoke with his head down, without looking any of us in the eye. I noticed that, while speaking, he held a large cicada between his fingers, which had surrendered to its fate.

‘The cooperative administration and the party secretary, on the last Sunday of the month, gathered the people in the square in front of the offices. On the doorstep, which was higher than the square, they slaughtered them – they slit the throats of the two seized pigs. “This is the end for animals kept outside the rules,” the cooperative leaders had said with determination.’

Silence again.

It was Mark’s despair that told us this; otherwise, we would not have believed that horrific, unheard-of event. In the first ten years after the war, enemies of the revolution were hung by the neck during the night in city squares and left hanging until the following evening. Those dead, hanging from the rope, swayed in the air for 24 hours so the city would learn what awaits the enemies of the proletariat. That criminal wickedness reminds me of Foucault’s Pendulum in Paris, which aimed to prove the Earth’s rotation, not to manifest human mediocrity.

The pigs were slaughtered in the middle of the day because they had not respected the Party’s rules. I thought of the guillotine and the heroes of the French Revolution. I did not understand why the idea of death terrified me. Whoever put their head under the guillotine was conscious of death. The slaughtered livestock, on the contrary, ended their lives without understanding the reason. I don’t know what the others thought. The idea of slaughtering two innocent animals as enemies of the revolution leaves one speechless.

Mark still had the large cicada in his fingers. Then, suddenly, he let it fly free. The choir of cicadas renewed its rhythm without worrying about the strange prohibition of our time. The sounds of that choir resembled a symphony greeting the sunset beyond the far horizon. The cicadas had scattered among the thick branches of the trees, enjoying the intimacy created by the olive grove. There wasn’t a soul around the sealed monastery, except for us and the thought of the slaughter of innocent livestock in Mark’s village. Thoughts and questions drifted in the air, seeking a human reason for that absurd execution in our friend’s village.”

Modern man, consumed by routine and the anxiety of daily life, hides from him the Evil that torments him and, with the help of propaganda, perceives very little suffering – he even feels strangely happy. Often, man experiences a virtual, alienated reality, lacking clear awareness of his own existence. Thus, he abandons passions, the longing for his neighbor, and talent; consequently, he loses the most human aspects that characterize him. These circumstances may favor the spontaneous, unconscious growth of nostalgias for the past and the dangers they carry. We must open our eyes and be prudent./Memorie.al

In every man, said Plato, sleeps a tyrant.

Terni, February 2022

Published in “Il Quotidiano Indipendente”, Milan (December 2021).

Published in “Rivista Dialoghi Mediterranei”, n. 53, Palermo (January 1, 2022).