From Shkëlqim Abazi

Part fifty-two

S P A Ç I

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My Memoirs and those of others)

Memorie.al / Now in old age, I feel obliged to confess my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds, and of others whom the regime silenced and buried in the nameless pits? In no case do I take upon myself to usurp the monopoly of truth or to claim laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, although I wholeheartedly tried to help my friends even slightly, who tactfully and kindly avoided me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months that followed, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard those three days, I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

So true is this that the artists par excellence were forced to give up their hobbies, and even suffer punishments, from being tied to posts, beatings, and solitary confinement, just so they would not be ashamed and denounced before the assembly (mexhlis), by slobbering in cheesy roles with brave partisans, cowardly Germans, and chicken-like Ballists, or by singing songs on the improvised stage for the Party and the working class, or by stigmatizing the lazy “tricksters” who sabotaged Albania’s progress, consequently hindering the realization of the plan and slowing down the pace of socialist progress.

The composer and instrumentalist Ali “Tromba” (Trumpet) once said to me: “I don’t know how to proceed, my friend, they know my professional abilities and absolutely demand that I direct the prison orchestra. They even promised me that they will grant me facilities take me out of the pyrite mine and put me on the surface, etc., but if I refuse, they will maximize my suffering. How would you act if you were in my position?”

I left with my head bowed; the decision was his, and I did not want to influence him with my intelligence. Although Ali was forced to accept, as the only composer and instrumentalist for many musical instruments, he made dignified music and did not pollute the repertoire with the songs of the communist baxhella (lowlifes). But some others acted differently, among them Dylber Starova, whom they had just brought in to serve his second sentence (he had finished the first one in the late fifties).

The virtuoso musicians, the Starova brothers, products of the most famous Italian school of the thirties, were highly sought after in the luxurious venues of Tirana, where the “fanatic” communists and the rare foreigners visiting socialist Albania entertained themselves, but also by the general public, who valued them for what they offered. But the regime could not stand them because of their biographical flaw: they genetically descended from the Starova beys (lords)!

Dylber was sentenced for the second time and brought to Spaç to contribute to the construction of socialism. One morning, I found myself in the 5th barrack, with my friends: Zef Ashta, Ismet Boletini, Qani Çollaku, Isuf Tufa, Riza Kamenica, etc., who slept in the section parallel to the dormitory above the abyss, where I was a resident. Surely, I must have gone there that day, either to look for a book from Ismet’s rich “library,” or for help in Italian from Zef, or to listen to the advice of the wise man from Dibra, or simply for jokes with Zaka.

When I arrived, I found them talking with a tall man, around fifty, worn-out and pale, but extremely serious and rude. As soon as they saw me, they interrupted the conversation. “An old friend!” – Qaniu introduced me and pointed to the stranger: – “My compatriot, Dylber Starova!” Of course, I had heard of him, but I was meeting him for the first time. When Dylber was brought in, Qaniu made space for him beside his pallet, as a fellow countryman; now it was time to get acquainted.

I was stunned by that ascetic appearance, which resembled no artist I had known until then; they were gentle, passionate, and even fragile sometimes, while this one was a majestic colossus. We were deep in conversation and did not notice a group of military officers, led by Shahin Skura and the head of the Technical Office, Medi Noku, who crossed the corridor and stopped right by my friends’ beds.

“This is Dylber Starova!” – Medi touched my acquaintance’s shoulder.

“You’re a convict, can’t you see that the comrade commissar has honored you and you’re sitting there as if you’re in a cafe!” – threatened one of the police officers.

Dylber changed color. As his body trembled, a nervous tic twitched his lower left eyelid (as I would learn, he had suffered trauma during his first imprisonment), he bent his head so as not to hit the boards of the upper bed and stood out taller than the others.

“Why didn’t you answer the call to become part of the artistic group’s orchestra, or do you think you are someone important?” – Shahin Skura lashed out at him.

“Before you brought me here, I was in orchestras; you separated me from my friends. But now I don’t know what you want from me?” – Dylber replied calmly.

“Hey, you, do you know who you are talking to? He is a commissar, and you are a convict!” – the police officer pointed a finger at him and stood on the tips of his boots, but couldn’t reach his chest.

“You have insulted the party leaders and violated the state laws, and they brought you here. Now we are giving you a chance to escape the mine,” – Shahini spoke seriously, with his fingers on his belt.

“Thank you for your concern, but I will choose the mine, with my fellow sufferers,” – Dylber replied.

“We’ll see how much the mine will appeal to you!” – the commissar headed for the exit, followed by his entourage.

From the conversation, we understood that Dylber had been proposed for the orchestra of the “Unit 303 variety show,” but he had not accepted. Now, the commissar repeated the proposal in front of others, but he openly refused.

That midnight, when we returned from the second shift, we learned that Dylber had ended up in solitary confinement. Naturally, the clash with the uncivilized Shahin Skura could not go without consequences.

As I mentioned, the “Unit 303 variety show, Spaç, Mirditë” was set up with some total failures (salla-topa) who could do everything wrong except art, but the failed offspring had a short life; it dissolved on its own after two or three extremely poor premieres, because even the command, with its sycophants, did not like it.

Nevertheless, the communist fabrication left behind a malignant transplant: the “Re-education Council,” the daughter of the Skrofetina camp, which was led by the patch-up artist (mballomaxhiu) and opportunist, Gani Tartari. But due to the political and moral composition of the contingent vegetating in Spaç, this “Council…” could not find a footing and was reduced to a scarecrow, only to scare away crows.

The “generous” shepherd, who in his youth had seen cannons in Ali Pasha’s castle and confused the cannonballs with footballs, pretended to be a sports enthusiast. He allowed them to set up a mini-volleyball court, to put two ping-pong tables; to add some chess boards, etc. These “concessions,” not sanctioned in any manual, spurred the ego of the elite athletes to briefly practice their old hobbies.

But the most significant “concession” was related to correspondence, meetings with families, the library, and the books they were allowed at that time for a short period. Now, correspondence was carried out, although control continued with a magnifying glass; the letters were not thrown into the mouth of the stove or the trash. The library was also enriched with some books that were either translations from socialist realism or tasteless products of mediocre writers, consequently becoming food for the stove.

We others enjoyed the story of the librarian, Robert Morava, a little more freely in the moving image of the prison. While meetings with family members were realized more easily and quickly, they did not wait for days and nights in the cold and heat of Spaç, and the drivers who traveled the roads of Mirdita also became more “generous”; they took them on the truck beds blackened by copper or pyrite ore and brought them back to Laç again on ore, naturally for a hefty reward.

As I mentioned, meetings were liberalized a bit during those times, even for visitors from Kosovo. One meeting was unlike any other. One noon, they called me, and a fraction of a second later, Ramë Tahiri (Rugova) as well. This selection worried me. I feared they would offer me solitary confinement for some “reserve” fault, even though the work had gone well those days, we had met the quota rhythmically, and I hadn’t rubbed against any police officer.

“Damn it, I’ve earned solitary confinement! Otherwise, they would have called me separately, and what’s more, with Rama, whose work is not connected to our brigade.” Although the weather was warm, I put on something thicker, to protect myself from the beating stick. Rama had arrived at the upper square before me.

“What could have happened that they are looking for us with such urgency, my friend?”

“What can I tell you, Malua must have made a mistake?” – I pinned the blame on the messenger.

“I don’t make mistakes, man, I’ve gotten the hang of the trade pretty well,” – Malua replied, having followed the replies. He wanted to add something else, but the police officer called him, from whom he returned after two minutes and snapped at me:

“Hey, man, are you going to take those bags, or are you going to leave your father to spend the night here!” In fact, only an hour separated us from the second shift.

I didn’t wait for him to repeat it, I ran to the warehouse, grabbed the satchels and some containers, and handed them to him, but he dropped them on the ground and turned to Rama:

“I don’t know if you need containers, for you the police officer only said this: ‘your mother has arrived’!”

“Please, Smail, see if someone is playing a trick, because if my mother were coming from Kosovo, she would have let me know!”

Rama was rightly unwilling to believe it, even though Tito and Enver softened those years and opened the border with Kosovo. They allowed visits from individuals or groups, naturally surveilled and censored. My friend’s mother took the opportunity to penetrate Albania, to see her son in prison. After five minutes, the messenger invited us from under the gate: “Come.”

The unexpected surprised Rama, who rushed to the gate without considering the guard’s reaction? “Turn back, or I will shoot!” threatened the soldier from the sentry box above the main entrance.

“Stop the charge, Ram!” – I squeezed his forearm.

“My mother has come, man!” – he snorted and tried to break free.

Rama had not seen his relatives since he came to the motherland to escape Serbian repression. As soon as he set foot here, they sent him to internment and from internment to prison, as Tito’s spy. Now, after so many years, his mother “broke through” the border legally and sought her beloved son.

Asking here and there, they directed her to Spaç, where he was serving his sentence. At the Milot bridge, she had accidentally met my father and my cousin, who had set off to see me. She begged them to orient her, and when she learned that they were also going there, they got into a vehicle and arrived together, at the same hour. Thus, they were also realizing the meeting at the same time.

“Mother!”

Rama retreated with his head bowed, like a lion in chains, but I held him tight:

“Slow down, man, or the soldier will shoot you!”

From the top of the stairs, I spotted my father and my cousin, across the gate, and with them a woman in the characteristic clothing of the Rugova highlands.

“Mother!” – Rama slipped out of my hands and rushed toward the gate.

“Stop or I will shoot!” – the soldier yelled from the sentry box.

“Let them approach!” – ordered the police officer who would monitor the meeting.

We became a mess, in two square meters: we, the prisoners, inside the wires; the police officer between the two enclosures; and the old woman from Rugova, my father, and my cousin, stretching their arms from across the barbed wire mesh, unable to touch even the tips of our fingers. Because we were all talking at once, the conversation was mixed up, so much so that it seemed the old woman was addressing me and my relatives were addressing Rama.

In the first moments, they broke down in tears; then Rama asked about the people at home, and the old woman answered him one by one.

When it came to one of his sons, she paused longer:

“A great trouble, my son, Tito put him in prison because he praised Bac Enver…”!

“Well, he deserved it, mother!” – Rama jumped in.

“What are you saying, my son?” – the old woman got irritated. – “Truly, Bac Enver needs to be praised, because he is the greatest Albanian after Skanderbeg, but not Tito, who is our enemy!”

“By God, mother, ever since I believed him, I’ve seen the worst of that villain, heavily…”!

At that moment, Fejzi Liçaj poked his head out of the guard officer’s office; Rama closed his mouth, but the military man seemed to play deaf, because he headed towards the command offices. The mother continued to narrate, in detail, the suffering the other son was enduring in Tito’s prisons:

“Forgive Bac Enver, my son, because you are in the motherland; a brother may eat your flesh, but he guards your bone! We can’t do anything for the other one, whom the Serbs have locked up in Goli Otok… but for you, we don’t have many worries!”

It is unknown how long the old woman would have continued with superlatives, had Rama not interrupted her: “Oh dear, mother, it is very bitter when your own dog bites you, but even the wolf guards your bone!”

Just then, Shahin Skura appeared, perhaps signaled by the operative. He greeted the old woman and turned to the guard officer: “Is the special meeting room free, Comrade Xhevdet?”

“As you command, Comrade Commissar! There are no planned meetings for today.”

“Well then, open it for this mother, so she can share her longing with her son; she hasn’t seen him for years,” – the fatherly commissar twisted his face into a forced smile.

“As you command, Comrade Commissar, but the key is with the logistics chief, who hasn’t returned yet from Rrëshen.”

While the commissar played the hypocrite, Xhevdet lied openly, because special meetings were for special people, and to secure one, you had to meet certain criteria that Rama did not fulfill. That is, you had to be a spy and a lapdog (legen) for the command.

“I apologize, mother; unfortunately, you will have to continue the meeting here!” Although he didn’t solve her problem, the old woman sincerely thanked him:

“Look how you…”!

“May your honor grow, Comrade…”

“He is a commissar, dear mother!” – completed the police officer monitoring the meeting.

“Thank you, Comrade Commissar!” – and the old woman turned to her son: – “Our brothers know how to behave!” Rama waited until Shahini left and replied:

“Indeed, I have been feeling their kindness on my back for years now!”

“Well, the Serbs never said a good word to us!” – the old woman continued on her own track.

“What can you expect from the enemy, mother, but when your own treats you worse, what can you say?” – Rama retorted.

“Well, I see you are very upset, my son, what has happened?” – the old woman worried.

“Do you want to see me worse than this, mother?!” – the son shot back instantly.

“By Allah, it is a shame to see you in prison, in the motherland!” – the old woman sobered up.

“Well, they have convicted me as Tito’s spy!”

“What are you saying?” – the old woman was speechless.

“Just as I told you…”!

“Enough talk about politics!” – the police officer intervened.

“We are not doing politics, sir!” – Rama objected.

“Worse still, you are insulting the Party and Comrade Enver!” – the police officer accused him.

“No sir, I am longing to see my mother!”

“Well, this mother of yours is clearer than you are!” – and he turned to the family members:

“The meeting is over!”

“I came from Rugova to see my son, officer, and you are chasing me away,” the old woman complained.

“Ten minutes have passed, dear mother!”

“Even the Serbs allow us longer, and even let us meet and talk like human beings, while you separate us with barbed wires, one on that side and the other on this side.”

“Our prisons have rules, dear mother!” – the police officer puffed up.

“Well, the boy is right, you are worse than the Serbs!” – the old woman protested.

The police officer blew his whistle; three others pushed the old woman across the fence, while the one inside snapped at him:

“All Titoists must be the same! Now you’ll see what you’ll have to endure!” And Rama, instead of being returned to the barrack with me, was thrown into a cell.

When they released him a month later, I learned that the old woman had been expelled as a persona non grata and deported that very day. The pear has its stem at the back (Dardha e ka bishtin prapa – a saying suggesting consequences come later); the Çelo-style experiment would not last long.

A pitch-black night with downpours, lightning, and thunder, in the valley (sqoll) where the stream rolling down from the mines met the collector brook – truly “the ideal place to escape on a dark, rainy, and stormy night” – Myftari from Dibra broke through the fence. Although they brought him back tied up to the middle of the camp two days later, he caused the repression to increase.

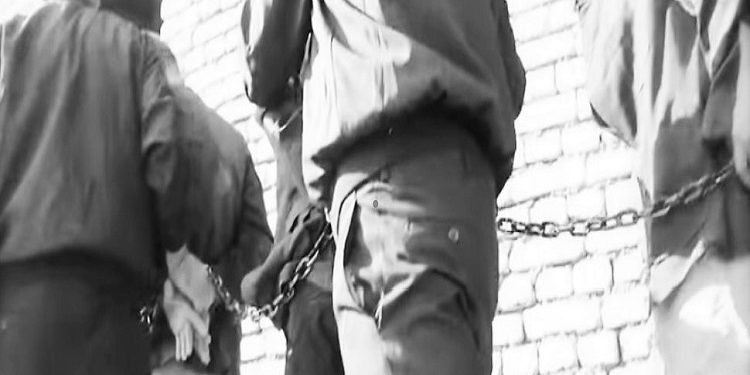

After this incident (kuturie), the violence would return harsh and bloody: goodbye entertainment, goodbye letters, goodbye books, goodbye family members! Beatings would rage every day, the tied-up would groan behind the posts, solitary cells would be full, and the cruel treatments would reach their peak in the Revolt of May 21, 1973, which would end with four people executed by firing squad and over eighty newly convicted.

But these things would happen later; let’s return to the past.

So, as I said, the pace of the class struggle seemed to slow down a bit, but arrests continued, perhaps not in the style of two or three years ago, but they continued nonetheless. Now they were sentencing the enemies of the second generation: the kulaks, the former merchants, the decadent intellectuals, and anyone who crossed their path.

In the years… ’70, ’71, ’72, television sets were introduced in the big cities. The state controlled them meticulously, but the clever ones (ustallarët) found a way; they constructed clandestine antennas, using “cans” on top of the mulberries, which caught signals from Italian and Yugoslav stations and transmitted programs from the free world. Thus, young people eager for denied freedoms and rights ignored the state and became promoters of the latest movements, thereby filling the vacuum left by Enverist propaganda. Beneath the veil of so-called popular democracy, a masked dissidence was being born. Or, did the communist authorities intentionally encourage the “loosening” (spanimin) of the transmission belts to gauge the pulse of the masses? The fact that the pace of the struggle decreased and happened in time intervals defies all imagination.

During the drastic decade (…’65-’70), the prison went to zero (they imported the Chinese Cultural Revolution, removed ranks in the army, destroyed religious objects, designed the Albanian life expectancy, expelled *kulaks* and enemies from the cities, etc.). The years that followed slightly loosened the rope and stimulated some secondary concessions, perhaps to observe the effect of the previous actions, only to then lash out with all possible harshness after the farce of the 11th Festival. Thus, artists, singers, composers, directors, elderly people, young people, men, and women from all social strata would end up in prison. Now, besides the traditional “enemies” and their derivatives, the revolution was eating the children it spawned.

Generals Gjin Marku, Halim Xhelo, the singer Sherif Merdani, the director of RTSH (Albanian Radio-Television) Todi Lubonja, the director Mihal Luarasi, etc., and even the offspring of the secret police (*sigurimsa*), the son of Asim Aliko, the nephews of Shefqet Peçi, etc., were clapped in prison. This category included a group from Tirana, composed of Gëzim Gazheli, Simon Hyka, an Agim… whose surname, if I’m not mistaken, was Xhani, etc., as well as two orphans from the “Children’s Home,” Dashnor Kazazi and Skender Daja. It was precisely these and other young people who brought to Spaç the echo of songs by Mina, Modugno, Celentano, the Beatles, and the most famous rock groups, as well as the fashion of long hair (although long hair was not allowed, the photos bypassed the barrier), cowboy pants, etc.

I have discussed how news reached the prisons in a separate chapter. Therefore, I will not dwell on the function of the “prison radio,” with its “infra” waves, which brought and carried everything from books and films to Western culture and fashion parades. On the other hand, the new convicts supplied the old prisoners, who had been cut off from active life for years, with every possible piece of information, thus keeping them in contact with the latest news happening in Albania and the world. The mythomaniacs there enriched the informative flow with fantasy, which they served up fresh. Memorie.al

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)