By Islam Spahija

Part One

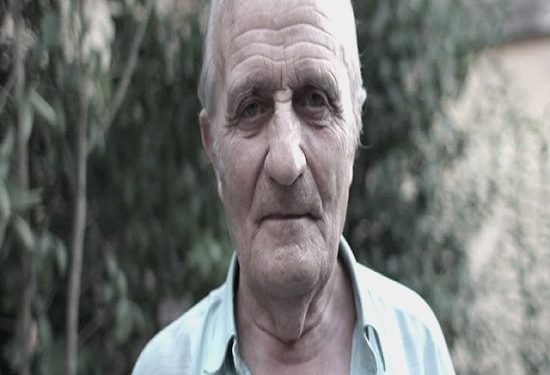

DOM LEC SAHATÇIA

Memorie.al / In prison, almost every day there were transfers or new convicts arrived; that hall there was a temporary hostel, for those who had just received their sentence and were waiting for the destination, where they would serve it. One day, while asking the newcomers as usual, I met an elderly man. His name was Lec Sahatçia. A sensation: “Are you the one whose name is on the ‘Lista dei collaboratori’, of Cordignano’s ‘Italian – Albanian’ dictionary”? – “Yes, my own”. How many times had I seen this name, when I picked up that dictionary! It appeared among other bright names, such as; Dom Ndre Mjeda, Dom Nikollë Gazulli, Dom Ndre Zadeja, Hamid Gjylbegaj etc…! Third in line, the former Dom Lec Sahatçia, with the note: “Parroco di Blinishti (Mirdizia), sopratutto per molta parte della lettera “S”. Now this man was suddenly appearing before me and I would not part from him, except at the moment when “Charon’s boat” would take us away from there.

Dom Leci was 71 years old when they brought him there. He told me that he had been a parish priest in Shpal (Blinisht) of Mirdita. The church where he had served, after the prohibition of religion, had been turned into a cattle feed warehouse, and now it is on top of a hill, reminds me of Dom Leci. Of course, it took some time to recognize the character of this special man. He did not appear, because he did not want to “be seen”; he let the other person understand it for himself. And, just as it happens when you first enter a dark room, and the eye does not immediately notice what is inside but, slowly acclimating, begins to notice things more and more, so it happens with some human natures, which have a deep spiritual world.

Like the heroes of Dostoevsky’s works, about whom Stefan Zweig says that; “they are not visible from the external lighting, but from the internal one and that, only when they ‘burn’, then their figure emerges”, so I would say about the figure of this martyr. First of all, I noticed that oval face, typical of the northern highlander. It was almost fleshless; a skull covered in skin, without blood. But something broke this sad image, something gave life to that “mask”, almost mortal: it was his eyes that were always alive, always mobile, always cheerful so much so that, if you met their gaze, you became, without realizing it, optimistic, even if you were in a desperate state. I tried to “investigate”, where this strange phenomenon lay.

Finally I found it and here it is: One day we happened to be in a group and were talking. There were endless stories; about the abandoned family, about the betrayal of a friend, about the death and illness of family members (mother, father, son and daughter…), about the long sentence and the little hope of seeing them. And again the relatives, etc…! As we listened, Dom Leci said to me aside, in a low voice: “All this will end one day…” – and raising his index finger, he added: “… that one never ends…” – Ah, – I said to myself – here lies the reason for the incomparable liveliness of those eyes, now I understand where he found pleasure! He believed in the afterlife, he believed in a God, with such conviction that they did not impress him; he even enjoyed the sufferings of this world.

At first I felt good for him, and then, to tell you the truth, I envied him; where could I get that titanic strength! But this holy man (undoubtedly), also knew the ordinary world: he even wanted to face it. He was stoic. Once, a convict of vulgar origin (there were many of them there), addressed Dom Leci: “You priests have had fun, you have…” – and he burst out laughing like a street urchin. All those present were silent with shyness, as if embarrassed. Dom Leci looked at him with a smile and did not answer. But this was not enough: this thing was repeated over and over again.

One day I could not contain myself and severely reprimanded the insulter. I remember that among other things I told him that; he should have considered it an honor to wipe that priest’s shoes; he was so inferior to him. From him, the filthiest insults would then be expected; this ultimately did not matter anymore, but I was indignant at the fact that; no one there came out alive, and so I was left alone. A little later I was surprised by that person; he had repented and asked for my forgiveness. I will never forget that apology; I shook his hand brotherly. Dom Leci, as a “prisoner” of this world, and as a native of Shkodra, felt the humor. Since he had no help (I did not find out if he had any relatives), he lived on the miserable prison soup. But the surprise: when others were starving, he ate without appetite, and often even made “slurs”. Besides tobacco, he really needed it.

I watched with pain as he picked up the cigarette butts that had been thrown on the floor. After taking out the unburned tobacco, carefully cleaning it, he would spread it on a piece of newspaper and then, again with the newspaper, he would roll cigarettes and smoke them with pleasure. Once I asked him, ironically, but with a compassionate irony, how my voice trembled: “Oh Dom Leci, where did you find that tobacco”? – “I planted it myself, I planted it myself” – he repeated with a laugh. He had a classical culture, he knew Latin. I really liked Latin phrases; I took the opportunity and often asked him, taking notes on a piece of paper. Ah! Goethe said that; “no matter what, life is beautiful”. I, like every being in this world, tried to find its beauty even in that place where it’s light had been turned off. And, I don’t know if I have upset this man of God like this, with my curiosity, I only know that he never, never gave such a sign.

Finally, the time would come for us to part, to never see each other again. We were in “Bajdos”, (airport) when the prison car (“Caron’s boat”) arrived to pick up those who had been transferred. I heard the name of Dom Lec, who had been assigned to the Ballsh camp. As had happened to me with Dom Mikel, I also began to look for him through the crowd; I saw later that he was doing the same thing; he was looking for me. We managed to shake hands and he, instead of saying goodbye, said to me: “Thank you from you.” Four years after I was released, I learned that Dom Lec Sahatçia had died in the Tirana Prison Hospital, in 1986. And every time I think about it, I seem to hear him say, as he used to: “Am I worthy to die for the faith of Christ?”

Spaç, 1977-1982

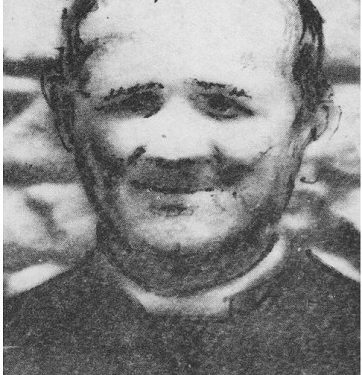

ZEF ASHTA

He had been an officer with the rank of captain, during the occupation. He had graduated from the military academy in (Italy). He was in Vlora, at the head of a battalion, at the moment of the Italian occupation: he welcomed it with arms, on his own initiative. With the arrival of the communist dictatorship in Albania, his luck had not been good, like many other patriots. He had been imprisoned, from the very first hours. He is now in the Spaç camp, having been sentenced for the third time. Previously he had been in the Maliq camp, doing forced labor, to drain the swamp. “Compared to that,” he would once say, “Spaç looks like a holiday home,” and he would recount gripping episodes.

When the topic of the role of the Great Powers in the history of Albania came up again, he got angry and said with a red face; “… leave England alone! She is the cause of all the evils of this country”! – and his eyes seemed to fill with tears and his cheeks swelled. I will never forget that withered face, with its “spicy” (all’italiana) mustache: it was completely gray. One could imagine what he must have been like when he was young (he was already close to seventy). Surely, one day he would have seen a white day.

Now he had to face his fate with stoicism, with the pride of a nobleman and the discipline of a soldier. Since he was old, he did not work; he lived on the miserable food of unemployment, on the “six-hundred”, as the bread ration was called, in prison jargon. I do not know why, he had no help from outside. I happened to be in the canteen once, when it was empty (after lunch had finished). There, in a corner, I saw Zef, late, who was barely eating the miserable camp soup. After a while, a prisoner entered with a large sack on his shoulder; he had the food that had just been brought from home. He was a Korça shepherd. He spread the food on the tables, creating a showcase of dishes, of the most diverse: roasted meats, pies, dairy products, and even baklava and cake.

Ah! Those who have not experienced it cannot understand the torture of hunger when it is provoked. Zefi saw this calmly, eating slowly, frowning. The owner of the goods approached him, with a piece of bread in his hand, and said: “Here… take it”! It was a dry prison ration, from who knows how many days! But poor Zefi, without raising his eyes, answered in a broken voice: “No… I don’t want it”! – Then I could not bear it, without venting to that orderly: “Take it! But is he a dog, who speaks in that way?! Then, since you are selling yourself to us as generous, why don’t you give him one of those foods with which you have filled the entire canteen? Is this manhood”?!

I don’t remember what he said to me: I know he cursed me as much as he could, like the old man he was, with the excuse “what do you need”? Cases like this have happened to me many times there.

Zefi, as a native of Shkodër, also had his own sense of humor. He had a reputation for knowing how to read coffee cups. One day he was drinking coffee in a corner of the camp, with Ndoka Gjeloshi, a very honest man from Gurëzi. The latter’s wife came to meet him once a month. That day, it happened that he didn’t come as usual, and he was worried. After they drank coffee, Ndoka asked him to look at his cup, and Zefi, after looking at it carefully, said: “Actually, according to the cup, no one is coming to meet you today; don’t worry.” At the same time, the herald was calling loudly, in all four corners of the camp, to inform Ndoka that his wife had arrived, while he, huddled in a corner, was listening to the prophecies from Zefi’s oracle.

When I heard this, I laughed with tears and often mentioned it jokingly, whenever I had the opportunity to talk to Ndoka, whom I loved very much. Once I asked Zefi, in good faith: “I saw God, do you really believe in fortune telling with cups”? – “No, my friend, I do it for fun, just to pass the time…! But, surprisingly, when it turns out that what I pluck in vain comes out, I myself am surprised, more than those who believe me”! We laughed heartily. Charlie Chaplin said that; “Humor springs from a heart full of sadness”.

One day, I experienced his end. He died suddenly in the toilets at the end of the camp yard, from a heart attack. Word spread quickly and the entire camp was in motion. I attended the “funeral”; yes, yes, a grand funeral, grander than those usually organized. It was improvised on the spot. His fellow sufferers carried him in a blanket that looked like a coffin. The blanket that covered him looked like the national flag to me; it had taken on those colors in my eyes; he was an ardent nationalist and deserved that honor. The entire camp immediately gathered (after all that was where everyone was). A two-line corridor was formed to pay his last respects.

The prisoners stood frozen, bareheaded, in mournful silence, as the corpse passed by. Suddenly I noticed the inner guard: strange! Not only did he not flinch, he did not object, as he usually did: (he was a bad guy; I had a run-in with him). But this time, on the contrary, he stood there, almost black in the face, at one end of that funeral procession. And so Zefi passed for the last time before our eyes, bidding us farewell without speaking, in that gloomy silence, where his ordeal was now ending. I do not know if his grave has been found, or if he has been lost like many others who died in that place. I do not know if he had any relatives; I know that he was unmarried. I do not know about the others who happened to him there, except for this one, I could never forget it.

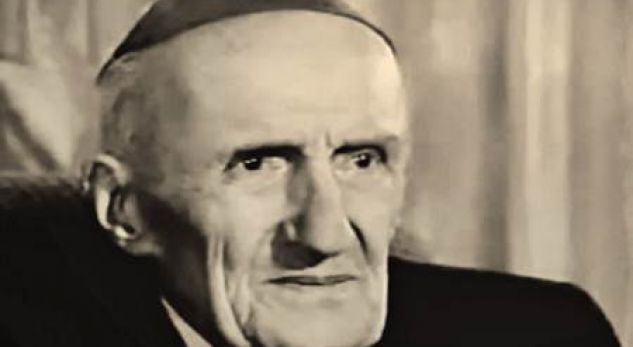

WITH DOM MIKEL KOLIQIN

The news of Cardinal Mikel Koliqi’s death touched me deeply and awakened a memory that has remained indelible in my memory. “Memory – said Jean Paul – is the only paradise from which we cannot be expelled”. Then, how can I forget the days I spent with Dom Mikeli, 21 years ago?! I was in prison in Tirana; July 1977. After I had passed the investigation, the trial and received the sentence, I would remain in “iron cage”, until my final destination was determined. In this way, condemned people came here almost every day, from all over the country. This reminded me of an episode that I had read in the “Divine Comedy” and, it seemed to me, I was living it. It seemed to me as if I were on the banks of the Acheron River, where sinners destined for Hell gathered.

And here are Dante’s verses: “Just as the autumn leaves rise/ One by one, while the branch/ Gives back to the earth, all its clothing/ So the evil seed of Adam/ Is thrown on that shore, one by one/ According to the signs, like birds by their calls/” (‘Inferno’, canto III). It seemed to me that I was hearing the cry of Charon, the rower of the macabre boat: “Woe to you, evil spirits! / Do not think that you will see the sky again. / I am coming to take you to the other shore. / In eternal darkness, in ice and heat” (ibid.). And, in truth, a part of us would go to the Spaç mine, in the heat of the pyrite galleries and in the ice of those of copper, in the eternal night of the underworld.

For a sentimentalist, this left nothing short of the fantasy, of Dante Alighieri’s genius. And wasn’t Dostoevsky right when he wrote: “What could be more fantastic for me than reality”? Thus, from time to time the door of the ” iron cage” would open, and the “sinners” brought by “Charon’s boat” would enter. Whenever a young man came, he would be subjected to the usual questions of the curious, such as: “Where are you from? What is your name? How long and why were you sentenced?” etc. Most of those who had just come out of the isolation cells answered without hesitation; even willingly told stories, as if they would ease their suffering. One day, among the others, came the one who would remain unforgettable for me. He sat next to me because there was a free seat there. He was a man of average build, about seventy. We introduced ourselves.

– “My name is Mikel Koliqi,” he said.

It was so that we would know each other’s last names. He had known some of my cousins during the internment in Lushnje, while I knew the name of the well-known author, Ernest Koliqi, who was his brother. – “I have a feeling of gratitude towards your brother,” I said, “because in the magazine ‘Signs’, which he runs in Rome, published an article about my grandfather, whose name I bear, in 1971. “I was in exile when I heard this by chance,” I said. He, after listening to me attentively, expressed surprise and seemed to fall into deep thought. It seems that he had lived so isolated that he did not even know about his brother. From that moment on, we were not separated as long as we stayed in “iron cage”. This lasted two or three months; I do not remember well. On the plank beds that stretched along the hall in the form of shelves with three floors, the convicts sat, ate, slept and talked together.

The conversations were endless, but they did not bore us, because they only connected us in some way with living human life. We relived it, through memory. From time to time I would get excited and recite the poems that I remembered, especially some song from the ‘Divine Comedy’, which this place constantly reminded me of. This had its own reason: the image of ‘Hell’ coincided with that reality. Dom Micheli, – that’s what we called him then, – listened to me attentively, so I thought he did this to please me or, out of the courtesy that characterized him. But one day he said to me: “Strange, we didn’t believe that there were still people your age who loved classical poetry, especially in our days”!? He was so correct, so polite, that I was afraid I might unintentionally upset him, and he didn’t tell me this. After a while, I learned a lot about his life.

Once we talked about the translations of his brother, Ernest, and specifically about the volume; “Great Poets of Italy”. “Those comments at the end of the book, I have elaborated myself”, – he told me with a smile, a little shy; shy lest he seem to be losing his mind. But I was very curious. Apparently he probed me about this and, wanting to please me more, continued: “I really like music. I know classical music quite well. Have you ever heard a classic song; ‘I protect it with my blood, I won’t let it go at all…’? I composed it myself.” “Yes,” I said, immediately illuminated by a spark of adolescent memory. “I heard it when I was 12 years old, at the ‘Normale’ school in Pristina, in 1943.” I remembered it like this: “Serbians left/ you have no place here/ I am Albanian/ I have a flag/ I protect it with my blood/ I won’t let it go at all”! I sang softly. “Yes,” he said, and he corrected the lyrics and music a little, singing softly too.

Later he told me about all his artistic activity, but I remember the names of the melodramas he had composed: “The Siege of Shkodra” and “Rozafa”, written by Dom Ndre Zadeja. I remember that we talked a lot about Fishta. I also had his case in the indictment. We were reciting verses from “Lahuta” with pleasure, when one day we heard someone nearby reciting: “The sun has set, in the sky a duel is brewing/ In Veleçik the Fairy is singing/ Hey you Albanian mountains/ In which shelters the breaking of freedom/ In the white times that have taken place/ Don’t let an enemy come near me”! I learned that this was a priest; it seems to me auspicious, with the surname Doçi. At that time, we wondered a lot: “Will the white times that have taken place come again”?!

Once we debated about French prose and compared two famous authors: Balzac and Dumas. In my opinion, the former stood artistically higher than the latter, and I tried to argue this. Dom Micheli opposed me, but I insisted on mine. Later, on another occasion, he was pleased with what we were talking about, but he said to me: “You’re fine, fine … but that day you insisted in vain, for Dumaas; you can’t just throw him away”! I laughed: “You’re very right, Dom Mikel”!

Finally, the moment of separation came. We were in “Pajtos” (that’s what the walking schedule in the prison yard was called), when the cartelist came out with a list in his hand and read the names of those who were to be transferred. Among them was Dom Mikel’s name. He was going to the Ballsh camp. At that moment, we happened to be far from each other. I saw that he was looking for me in the crowd and, pushing through the others, I approached him, but the inner guard stopped me. Then Dom Mikel addressed him, in a pleading voice: “Let me, if you want, go with you alone,” – and pointed at me. We met and He, shaking my hand, raised his eyes to the sky and, with a trembling voice, said: “May God grant that I may see him again”! We, from that moment on, never saw each other again! /Memorie.al

Continues next issue