By Njazi Nelaj & Petrit Bebeçi

Part Four

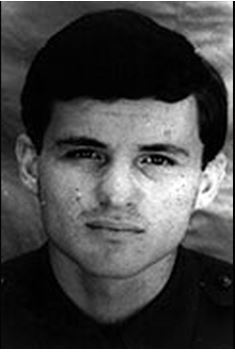

“That morning, fate was not with the Commissar!”

Memorie.al / Luto Refat Sadikaj ranks among the “elite” pilots of Albanian aviation of all time. He was part of the first group of pilots trained entirely from the beginning at the aviation school in Vlorë. Thus, Luto Sadikaj was “100% home-grown.” Not only that, he perfected his skills up to the sophisticated MiG-21 aircraft on Albanian airfields, under local instructors, and following Albanian regulations – at a time when limits were constantly decreasing and two-seater training planes were unavailable. This is perhaps a unique case in the world history of combat aviation.

Continued from the last issue…

“Luto Sadikaj was very confident in his work. He worked without deceit, and his sincerity was evident. He was deeply human; a simple man and a devoted family man. Luto’s commitment to his family was rare. His love for his daughter, Gresa, was perhaps a perfect model of fatherly love. When playing football, Luto was unstoppable. He kicked hard and accurately, especially with his left foot. Barefoot, Luto hit the ball better than with shoes on.

While on vacation at the military convalescence home in Durrës, the then-coach of the ‘Partizani’ team, the well-known Bejkush Birçe, would recruit Luto every day for 30 minutes to train the team’s goalkeeper, Perlat Musta. Bejkushi knew Luto had a powerful and precise shot, so he would plead with him to kick barefoot! One day, the Gjadër regiment’s football team played against the Rinas regiment. We were friends, but in that match, we were opponents. Luto was highly competitive.

He wanted victory on his side, but only through fairness. In the Gjadër team, Luto was the leader. During that game, the referee awarded a penalty to Gjadër. Luto grabbed the ball and placed it on the 11-meter mark. He was going to take it himself and took off his left shoe. The referee objected, citing regulations. Luto insisted on kicking barefoot. As an opponent, I stood with the referee, but Luto wouldn’t listen – he took the penalty barefoot and scored.”

The Rise to Commissar

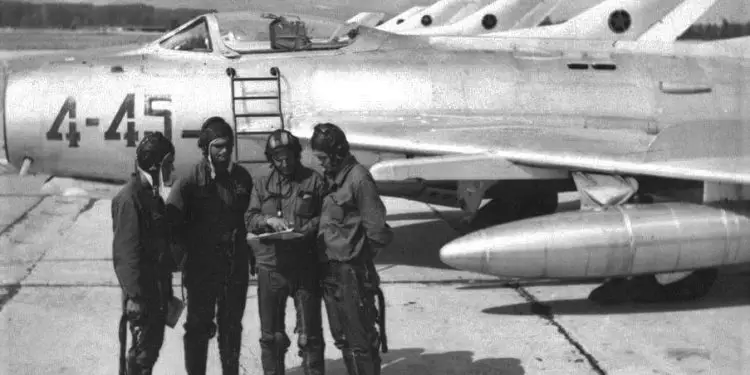

Myzafer remembers his bond with Luto as a pure friendship of colleagues where the influence was mutual. Luto climbed the military hierarchy step by step and was appointed Commissar of the new Gjadër Regiment. The commander was the exceptional pilot Dhori Nasi Zhezha. They were an extraordinary pair: two friends and great colleagues.

They flew the sophisticated MiG-21, an aircraft they never abandoned. As Commissar, Luto had to handle a wide range of personnel issues, yet he never shirked his flying duties. When a MiG-21 taxied to the start, Luto was there at the forefront, leading by example – not with words, but through flight. His professional pride and combat pilot traits pushed him toward the greatest difficulties and imminent risks.

One particularly difficult case occurred when Luto was flying a supersonic MiG-21 that had just undergone repairs. He took off to reach speeds twice the speed of sound. His close friend, Petrit Bebeçi, recalls: “At an altitude of 13,000 m, when the speed reached 1,920 km/h (Mach 1.8), the engine began to surge (pumping), and neither the engine nor the plane responded to commands. Through his skill as a class-A pilot, Luto managed to escape that critical situation.”

The Tragedy of March 29, 1982

However, the tricks of the sky did not end there. On the morning of March 29, 1982, fate turned against him. It was a routine flight day. Luto was to take off in MiG-21, tail number 108, for an aerial interception exercise.

Just moments after lifting off the ground, tragedy struck. A flock of seagulls, scavenging in the nearby freshly plowed fields, was startled. As Luto’s plane was in the critical phase of takeoff, several seagulls were sucked into the engine intake of aircraft ‘108’.

The MiG-21 engine intake does not have a metal screen to block birds. The seagulls hit the turbine blades, which rotate at staggering speeds, causing them to break and leading to immediate engine surging. The engine power dropped drastically; the plane could no longer climb.

Witnesses saw a yellow-green flame envelop the fuselage and heard a muffled thud from the engine. Luto, with his vast experience, tried to gain altitude, but the aircraft would not obey. Seeing the plane falling toward the earth and realizing the concrete runway was behind him, he reacted quickly to land the plane directly ahead in the “green strip” (emergency grass strip).

The plane touched down 150 meters into the field. Neither the safety sand strips nor the grass could stop it; it finally halted near the Gjadër river bank, close to a cluster of houses, in a semi-inverted position. Luto tried to open the cockpit canopy, but the ten locking pins were deformed from the impact. The safety hook was jammed.

The Final Heroic Act

Two local villagers from Gjadër rushed to the scene. Luto signaled them to try and smash the canopy. They tried with whatever tools they had, but it was impossible. Time was running out. Luto, realizing the aircraft was about to explode, signaled the villagers to run away immediately to save their lives. Seconds after they retreated, the plane exploded in a ball of fire. Luto Sadikaj, a true giant of a man, remained inside and lost his life.

This act – protecting the lives of two strangers while facing his own certain death – is the ultimate proof of his character. Firefighters and rescue teams arrived quickly, but it was too late. His body was transported to the Lezhë hospital and then to his family.

Legacy and Honor

Luto Refat Sadikaj was an elite pilot, an exemplary parent, and a devoted citizen. He served as a member of the People’s Council of Lezhë and was known for his charity, often giving his own clothes to the poor. On March 30, 1982, by a special government decree, Luto Sadikaj was declared a “Martyr of the Fatherland” (Dëshmor i Atdheut). He was laid to rest in the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Tirana, in the section dedicated to pilots fallen in the line of duty.

Following the disaster, flights were suspended for two weeks for analysis. It was concluded that the cause was external and undeniable (bird strike). To regain morale, the regiment leaders – Dhori Nasi Zhezha and Petrit Bebeçi – took to the skies first to show that the “blood” was once again circulating through the regiment’s veins.

Luto Sadikaj was not just a pilot; he was a personality. His role as Commissar was taxing, requiring him to balance the psychological needs of the soldiers with the extreme technical demands of flying a MiG-21. He sacrificed much to stay at the required level of both duties.

Though years have passed, the memory of Luto Sadikaj remains eternal. He “extinguished” in the prime of his life and at the peak of his professional maturity. May his soul shine and rest in peace!/Memorie.al