By Taisa Batkina Pine

Part nine

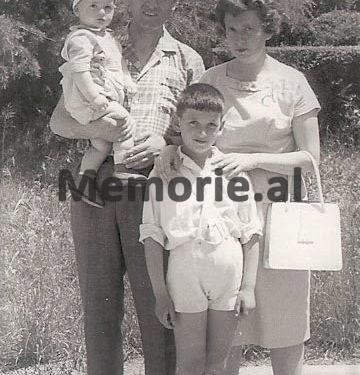

Memorie.al/publishes the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was left an orphan at a very young age, after her father lost his life while working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner, (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with difficulty great economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, which had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, and began life in the city of Tirana, where Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkina on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to 16 years in political prison, which she suffered. in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, in Memorie.al

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

This is a book of memories. In it I want to tell about my life and that of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because we… fell in love! And let no one ever forget what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

Continued from the previous issue

In the rest of the book I will write in more detail about these women, so kind and so unfortunate, that with their help and solidarity, they embellished the horrible reality. I told you, our camp was on a hill, there were no walls around, but barbed wire; the hills, the fields, and the road to bring to camp were visible. The hills were green almost all year round. They became especially beautiful in autumn and winter, when they were covered with the most varied colors, from the green of winter corn, leek fields, bushes of various kinds and other plants…! But when we went out in the spring the fields all blossomed, intoxicated by the scent of the yellow flowers of the brook, the bushes of the wild pink rose, the poppies that glistened like red lights. The thorn bushes bloomed, the fields planted with sunflower and wheat that had such a pleasant aroma turned yellow. We were so tired that we could hardly stand, our hands were full of bubbles and spikes of wood, but when we approached the sheaves of wheat, from the pleasant aroma, as if we were relieved, as if someone was taking away our fatigue by hand. The healing action of nature on the wounds of the soul, helps you for a moment to forget that it marches under the watchful eye of the guards, who at any moment may call upon you in a rude voice, push you, or strike you; that after a while you will enter the camp surrounded by barbed wire, that you are in prison, because you feel completely under the power of an unprecedented beauty.

Working in the fields also fed us!

I told you that for the realization of the norm we were paid a little and with that money you could buy something in the camp shop, but the main ones were the ones you could bring from the field. Very rarely, as far as I remember only once or twice, we were allowed to take a few potatoes from the field during the harvest, while we usually “stole”. From the fields we brought corn, potatoes, wheat, sunflower, whatever we could, and everything edible. These were very valuable to us; they were food, calories, and vitamins. It was easy to get them; it was hard to put them in the camp, because such a thing was strictly forbidden. The brigades stood for hours in front of the gate, everyone was carefully checked, piles of “seized goods” were erected on the side of the road; however, we managed to introduce quite a bit. We used all sorts of tricks: we sewed hidden inside pockets in pants, t-shirts, bags, hid in socks, under hats, in spark plugs. It was easy to hide something in the vandals and at first many people used this method, but very soon the guards tricked him and started asking us to solve the vandals. During the sunflower harvest, Vola and I invented something else: we took a piece of plastic (such old pieces were full in the hills because they served as packaging at work), we filled it with sunflower seeds, wrapped it and put it in a piece. Another plastic, which served as the binder of the candlestick or sunflower springs. By order of the guard we solved the vandal, and the package of seeds could not be found, because it was under the spark plug and did not appear. Despite the strict controls, during the sunflower harvest the whole territory of the camp was covered with a layer of seed husks.

When I got out of prison and read Solzhenitsyn’s novel “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” for the first time, it seemed to me that it was written for us. Same thing, so rough, so similar. And it was not surprising; the same camp, the same system, similar charges, and the same problems. The key was to adapt, dodge and survive. The villagers taught us how to gather useful herbs, which ones to boil, which ones to eat as they were. “In the spring you have to eat greens. “They cleanse the blood,” they told us. What we did not try then: sorrel, poppy leaves, labia, rapeseed, chicory, dandelion, and strawberry. Once, at the beginning of spring, we gathered fresh nettles and ate them alive, after pressing them in advance, so that they would not burn us. We ate a lot because we were hungry and they looked very tasty, but the next day our stomachs ached. Sunday was a day off, but if the camp command needed money or there was urgent work on the farm, we were fired. It happened that we worked 3-4 weeks non-stop on Sundays. But even when we stayed in the camp, the bosses would invent a job for us. The camp was new and we for a long time, dealt with the arrangement of the rocky slopes of the hills in its territory. We erected defensive walls, removed large stones, and leveled the ground. We built the kitchen for ourselves. We were often forced to dig up the soil in the belt near the barbed wire, lead us to get straw and refill the mattresses, or bring coal unloaded from trucks, or stack stacked timber. This was the best job because after we finished, they allowed us to get some wood for ourselves. On Sundays they often checked us out. They took us all out to the yard, where we waited for half a day.

My field work lasted close to three years. My legs swelled as I could barely walk. The medical commission, during one of the rare visits to the camp, diagnosed me with “varicose veins” and took me to light work. With such a diagnosis, in fact, I did not have to work, just stay in the camp. But this was very difficult; any kind of work as if to facilitate existence. Some work or task to distract the mind from strenuous meditations. Then… was also the food earned by work…! During my many years in the camp, I also worked in our large garden, under construction, in arranging the camp territory. We planted trees, covered the hillsides with grass, and grew flowers. I worked in the pigsty, washed the toilets, and my most honorable job was as a storekeeper and waitress in a canteen. (The latter, unfortunately, did not last long, because other women came out, looking for her). When I worked as a cleaner, every two weeks I had to whitewash all the ancillary premises, the retaining walls, the canteen. Such work never closed the wounds on my hands. In the camp they set up a pig stable and started keeping pigs. Baresha appointed Liza, a peasant from the north, from a Catholic village. (Catholics in northern Albania raised pigs). Liza was a silent, independent, proud woman, she understood everything. He never talked about himself. They made me her assistant. Eternal city dweller I had never had anything to do with animals other than cats.

The first day Liza told me to graze three big pigs. I knew from the books that pigs like to crawl in the mud, so I took them to a canal at the foot of the hill. When he saw them, Liza put her hands on her head. We barely left and cleaned the pigs and since that day, I have not made such mistakes. Then Lisa was replaced by another woman, Lucia, also from the north. She was young, strong, accustomed to that job, and she loved pigs. But as a man she was wicked, intriguing and spy. We tried to keep them as far away as possible. At work I only talked about what connected us there, nothing else. When she started a conversation on a dubious topic, I was removed as flawed. The work was hard; we had large herd. We carried food tanks for pigs, bags of grass, bran, boiled them, and even cleaned the thank. Pigs had to be fed, grazed, cleaned, and pigs required special care. Lucia slaughtered the pigs herself, stripping them and chopping them. I could not help him in this work, I even left the hearth as much as I could. This took away the essence of my flesh, with which the camp economist rewarded Lucien for his good work, but I could not do otherwise. And I never learned to slaughter pigs. In the camp I learned to make brooms… there was such work. We planted the millet ourselves, then made brooms for ourselves and sold them.

Camp staff

Our life in the camp depended entirely on the command team, service officers, guards. They were very different, between stupid, rude and mean people, matches and not bad people. Often the savagery of the overseers grew out of fear. They were all afraid of each other, they were afraid of us too. Their every action, every word could be distorted and serve as a motive for espionage. Spying had become the norm in freedom, and in its organs, prisons, and camps, it flourished. It is not in vain that Enver Hoxha, in one of his many speeches, said that: “we must see every report; “Even if they contain only five percent of the truth, the matter must be investigated.”

In the men’s camps the staff was very savage, but among them, really rarely, there were people who, even in such conditions, tried to do well. The Albanian poet Maks Velo, who spent many years in prison, wrote about such a man in one of his poems: “You carry the party card on your chest / Of course, what are you proud of / You saved some lives. And we, we saved you / We did not want to lose you “. The women’s camp stood out for the slightly milder regime. I want to talk a little longer about the director of the prison. He was a mature man, a former investigator. He was a fair man and a good host. He suffered from a heart attack and died shortly after retiring. The prisoners with “internship” said this about him: “From the position he has, this man cannot do anything good for the prisoners, but what matters is that he does not hurt them”. She had worked for many years in the State Security organs and realized that the “enemy” women had not committed any crime, but were unfortunate victims of the regime and the conditions. He could not set us free, nor could He reduce our punishment, but He did what was in His power. He could allow a long meeting more, get you to easy work, give some clothes to the needy and many others, which at first glance seemed small and insignificant things, but in prison conditions weighed a lot. Our principal tried to make our lives a little better; managed to replace the flea beds of the camp, filled with fleas, with two-story iron beds, although old. They gave us sheets to make the beds… (He loved cleanliness).

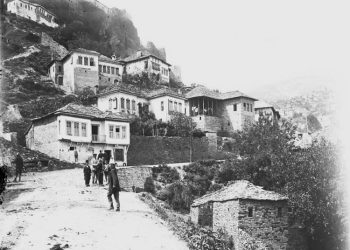

The director treated the disciplined, calm, good-working women well and with respect, and he could not stand the immorality and the thieves, who made trouble, did not work, stole. He did not leave any serious violations of them unpunished, but never brought the matter to retrial. There was only one women’s camp in Albania. At first it was located in the center of the country, near the City of Stalin (today’s Kuçova). The camp there was small, and women prisoners were constantly coming. There was not enough water, there was no work. I know something about the old camp from the words of the women, who had spent part of their sentence there, which for most prisoners was many years. Conditions there had been very harsh, almost like those of a prison. A new camp was built in a place far from the center and national roads, near the village of Kosova in Lushnja. They moved to the new camp in early 1977, shortly before they brought us to the camp. Our director loved the land very much, he knew well from the affairs of agriculture. A 3-hectare garden was opened around the camp. The director took care of the good irrigation of the garden, sent for work there the best and strong workers. We got such production from him, that all year round we could supply the kitchen with vegetables (there were about 600 prisoners in the camp), and even sold. Around the colony we planted many trees; poplars, pines, fruit trees, and in the camp, we planted gardens. The director brought the seeds and seedlings himself. The flowers were planted by Nadja, I helped her. How many buckets of water a day we had to bring, how much soil was dug! The results pleased us. We grew many good flowers, roses, carnations, velvets, chrysanthemums, peony flowers and many other beautiful flowers. I will never forget them.

In those horrible prison conditions, beyond the barbed wire, with armed guards at the top of the towers, for us, women separated from families, men, children, with crippled fortunes, the flowers we cared for, were a real relief. The gardens where we could relax, read, sew or knit in our spare time, were like oases in the desert, like a sip of cold water, beauty, freshness, joy. As the malefactors put it, the director could hide his interests. If the camp looked good, clean, beautiful, the chiefs praised him and he took first places in many directions among the other camps. But we did not want to know if the director had his own interests or not. What mattered to us was the fact that the camp was clean, flowery, and green. The director was well aware of the value of prison espionage and, in most cases, threw it in the trash. How good our director was, we realized when he retired and in his place they brought a “chariot horse”, a wicked and angry man. He trusted every spy, screamed, yelled, and tortured us with checks and all sorts of deprivations. The new director liked to mumble near the barbed wire with ordinary prison girls and half-crazy prisoners like Nusha. With the arrival of the new director, our flowers withered and nothing grew in the garden. We could hardly feed some pigs. According to the regulations, there were two small meeting rooms in the camp. One across the wires, for ordinary, short meetings, where women and visitors sat and talked under the supervision of the guards. The other was near the gate, inside the camp territory, for 10-12 hour meetings. Sometimes there we were allowed to meet girls, sisters, mothers…! Often such meetings were used as rewards.

Meetings there were usually held from evening until morning, at night no one could approach the lodge. But the new director canceled the long meetings completely, and the usual ones took place by the wires, near the gate. People stood on either side of the wires and talked in the eyes of the two guards, often in torrential rain or scorching sun. No meeting, but torture…! The women guards of the camp were mostly young girls from the surrounding villages. Judging by their behavior, it was understood that the prison director had carefully selected and instructed them and they treated us calmly. But we also tried to stay away from them, not to enter into conversations, not to provoke debates. Some of the guards tried to take advantage of the work of the prisoners, to ask us to embroider them, to sew them. But they were afraid that we would not report them, because the bosses strictly forbade any kind of relationship between us and our guards, so the latter, with a lot of fear, took the courage to ask for any service from us. One of the guards had been a thief. We noticed that during the checks, they lost our belongings. The thief was spotted, reported and we did not see him again. The wildest among our guards was Zela, wicked, wicked; we inherited it from the old camp. When she was on duty, we had to keep our ears open. She always spied on us, provoked us, shouted at us and punished us. Peel a squash, grate it and squeeze the juice. We were left without a spoon, we had to find another one and sharpen it. Zela tried to stop us from talking to each other in Russian, but he did not walk. We insisted, we reacted sharply, we told him that he has no right to prevent us from speaking in our mother tongue. No one listened to her request and she was forced to withdraw.

I mentioned above that, among the prisoners in the ordinary sector, there were many misappropriates of common property. They had stolen a lot and here in prison they lived apart from others, many visitors came to the meeting and brought them many things. This was called the wealthy aristocracy of the camp. They often ordered embroidery, drawings, knitting in our corps. At camp we had our prices, unlike any other. Poor women, in need, hungry, embroidered, knitted for a ridiculous payment in nature: a little sugar, flour, etc. Prison work was estimated 6-8 times cheaper than abroad. Vola once got such a job. Suddenly, when half the work was done, we were told that any kind of handicraft was forbidden. (Such things often happened in the camp, sometimes they forbade us something, and sometimes they allowed us). How to do? The work had to be done definitely. We had received the payment and it. Vola started embroidering in a hurry, sitting on the second floor of the high bed, ready to hide the work and pull out the book for any occasion. I was guarding the door, behind the stairs. Our room was at the bottom of the building. Suddenly I saw Zela, who was running down the stairs, eating her legs. I hurried to the room. But other women, who happened to be closer, realized how the work was going and informed Vola. Zela slowly entered the room and approached Vola. He looked like a predator approaching his host. But Vola, quite calmly, read the newspaper. “Where is your handiwork?” Zela asked with clenched teeth. “Embroidery”?! – was Vola hosts. – “Embroidery is forbidden”! Zela picked up the pillow, the blankets. There was nothing! And he had no choice but to leave. It was learned that someone had reported. Such zeal was abundant in the camp. But there was also solidarity, mutual help. It does not matter who helped, one of our women, or the Albanian ones, it does matter that Vola was informed in time. The Guardian Almonds enjoyed the sympathy of all. Young girl, round-faced, rosy, gentle, she was very human, she tried to help others as much as she could. We rejoiced when she was on duty, or accompanied the brigade to the field. When the medical commission came and visited us for the first time, Bajamja was in the service. The doctor, chairman of the commission, asked me if I found it difficult to work in the field. I could not open my mouth, because Bajamja answered: “Yes, they have it very difficult, they try hard, but they cannot”. Once, when I was a pig herdsman, we got a cabbage head from the garden. /Memorie.al

The next issue follows