By Bashkim Trenova

Part eighteen

Memorie.al publishes the memoirs of the well-known journalist, publicist, translator, researcher, writer, playwright and diplomat, Bashkim Trenova, who after graduating from the Faculty of History and Philology of the State University of Tirana, in 1966 was appointed a journalist at Radio- Tirana in its Foreign Directorate, where he worked until 1975, when he was appointed as a journalist and head of the foreign editorial office of the newspaper ‘Zeri i Popullit’, a body of the Central Committee of the ALP. In the years 1984-1990, he served as chairman of the Publishing Branch in the General Directorate of State Archives and after the first free elections in Albania, in March 1991, he was appointed to the newspaper ‘Rilindja Demokratike’, initially as deputy / editor-in-chief and then its editor-in-chief, until 1994, when he was appointed to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the position of Press Director and spokesperson of that ministry. In 1997, Trenova was appointed Ambassador of Albania to the Kingdom of Belgium and to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Unknown memories of Mr. Trenova, starting from the war period, his childhood, college years, professional career as a journalist and researcher at Radio Tirana, the newspaper ‘People’s Voice’ and the Central State Archive, where he served until the fall of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha, a period of time when he in different circumstances became acquainted with some of the ‘reactionary families’ and their sucklings, whom he described with a rare skill in a book of memoirs published in 2012, entitled’ Enemies of the people ‘and now brings them to the readers of Memorie.al

Continued from the previous issue

“Enemies of the people”

Departure from RTSH, of the conductor of the symphony orchestra, master Gaspër Çurçia!

In the music sector on Radio Tirana, the blow will have even more tragic consequences for trumpeter Gaspër Çurçia. Personally, I did not have any friendship or friendship with Gaspër Çurçina. I have known her during the years I worked at the Albanian Radio-Television, we greeted each other when we met in the corridors of the Radio or in the small cafe in Sultania, an agile woman, ready to answer anyone, at any moment, while preparing the cups of coffee or small plates with a half panini and a sausage.

I heard different opinions about Gasprin, which came together in a unanimous assessment of him as a “brilliant” instrumentalist. Another thing he is not wrong about when he talks about Gaspër Çurçinë, is his noisy humor, which is ubiquitous as it always happened.

Colleagues and we who know him remember Gasprin as a passionate man, as a man of bold enterprises for the time. He was the one who created for the first time a Big-Band formation (orchestra of 12-25 musicians playing instruments, such as saxophone, trumpets, trombones, pianoforte, etc.) consisting of 10-15 musicians. With this formation he recorded about 30-40 pieces that are still preserved today in the sound library of Radio Tirana. With this formation, Çurçia will appear for the first time to the public at the end of December 1972, at the 11th Song Festival on Radio-Television. The end of the Festival will be the end of Gaspër Çurçi’s brilliance. He was hit hard, never to rise again, as a liberal, as a propagandist of bourgeois and decadent music, etc., etc. He was fired from the Radio and ordered to move to Peshkopi, a mountain town in the north-east of the country. Gaspri refuses to go to Peshkopi, refuses to be separated from his family.

“I remember that he started working as a guard at the Teaching Aids and that he received his salary where the idiots received it, but he did not give up”, Gaspri’s friend, the well-known composer, Aleksandër Lalo, confessed years later in a press interview. Gaspri again manages to form a musical formation of his own, justified this time as an orchestra with folk instruments. So perhaps he intended to show the government that he was relying on the people, that he had found inspiration in the people that he had moved away from the harmful bourgeois-decadent past! Perhaps this was the only way through which he saw himself again on stage, again in front of the public, again adored, especially by the youth. With the new formation he also gave a performance at the Palace of Culture of the capital.

Gaspri had it in vain. His project failed, he was accused that the music of the new formation did not sound Albanian. The “gods” of the only atheist country in the world, as stated in its Constitution Albania, had made their decision for it. Gaspri had to suffer, go and get his salary there with the hawks, be despised, forgotten, even be grateful because it was worse!

Gaspri was sentenced to death and shot!

For Gasprin it would really be even worse. In the face of the great difficulties that were created for him, with a perspective lost forever, in despair, he makes the mistake that would cost him his life. In financial need, Gaspri agrees to cooperate with a train ticket seller, make fake tickets and profit a part from their sale. He was arrested and sentenced to death by the trial panel. Before the court, Gaspri did not deny what he had done. He acknowledged the fraud, but added that what he had gained from it was “a very small fraction, compared to what the state had seized from his parents” as traders. This was Gaspri. There he played with his life, he mocked death. Gaspri was sentenced to death by the court.

One night, in April 1985, Gasprin, Shkëlzen Doçin, a 35-year-old engineer, also sentenced to death for forging train tickets, and an ordinary murderer, were sent to the place of execution, in Linza, Dajti Mountain. , near the capital. They placed them near a large open pit during the day, and placed them on its edge with their hands tied with wires and their legs dangling, looking down toward the depths that would swallow them.

The execution procedure required even at that time that the convict express his last wish. Shkëlzen Doçi, hoping until the end that he could be forgiven, mechanically repeated the usual praises for Enver Hoxha’s Party and Marxism-Leninism! He showed great longing for his mother, whom he had not seen for a long time, since he was sentenced to death and had been isolated in a high-security cell, with a helmet on his head and handcuffed to him. ‘Prevented suicide’. Finally he asked for a cigarette. He smoked it as if he wanted to take advantage of the last particles of life, which in a few moments would turn into nothingness, like cigarette smoke.

Gaspër Çurçia did not mention either Enver or the Labor Party. He said that he was being shot unjustly, because the Criminal Code did not provide for this punishment for the amount of money he had embezzled, an amount of 20,000 ALL, as a good salary for two months of work. He kept calm and left the children with dignity. She knew that the children of the victim would also be “shot” for life, discriminated against at every step, and “touched” hopelessly. For them, he probably even made the fatal mistake. He could not help but think of them even in the last moments, in the last message before they parted and left forever.

We all imagine the shooting as in the movies, a platoon lined up a school with guns aimed at convicts with their eyes and hands tied, an officer ready to give command. Gaspër Çurçia and two others close to him were not executed like this. There were three policemen who, after loading the pistols, kissed the convicts at the base of the ear and shot so that the bullet penetrated the two hemispheres of their brains. Shortly afterwards they pushed the bodies into the pit.

One night after the execution of Gaspër Çurçia, the dictator Enver Hoxha also died. Gaspri is the last page of his monstrous crimes chapter, but not of his crime policy, which his followers will pursue for several more years, as long as they were in power, down to their throes of last.

After the overthrow of communism, the family, Gaspri’s children, managed to learn the place where their father was shot. In 1992, they dug a joint pit where they found the bodies of three gunmen and the wires that had tied their hands. Many Albanian families hurried after the overthrow of communism to search for the remains of relatives even without the presence of specialists, even without accurate data on the location of the grave or graves. Many of them took unidentified bones, considering them as the bones of father, mother, brother or sister. This did not happen to Gaspri’s two sons. As they will say, they were “lucky”, they provided accurate data in advance, but not only that.

The composition of the soil had made possible the good conservation of the three shot even after seven years. The children recognized the father’s body, who could not say goodbye to him. They recognized his jacket, sweater, and his shoes. They took what was left of Gaspër Çurçia, a handful of bones, a skeleton to honor him as every parent deserves, every good man, even though forced, can make any mistake, even guilt, in life.

Gaspër Çurçia has not remained in the minds of Albanians as a convict for forging train tickets. Contemporaries respectfully remember his brilliance as a musician, interpretation and creativity, from which was deprived not only Gaspri and his admirers, but also Albanian music.

The departure of the poet Sadik Bejko from Radio Tirana, as a miner in Memaliaj!

Apart from the musicians, others have also been hit hard on the Albanian Radio-Television, such as Sadik Bejko, the poetry editor, or Edi Hila, the painter. The regime was afraid of the people of art, of the truth, that art conveys forcefully in life, life itself as it is, with all its colors, with pains, sacrifices, with hypocrisy and faith, friendship and betrayal, human and demonic. He terrorized them to tell only his “truth”, to make us see only one color, red, to hear only one poem, the one dedicated to Enver Hoxha and the Labor Party, to “enjoy” a life, what was denied to us.

I remember Sadiku when he started working in Radio. Almost like the rest of us, the newcomer was somewhat withdrawn, almost shy and quite polite, speaking in a baritone, radio voice. I probably would not have noticed it if a friend of our Editorial Office, Natasha Cerga, had not written poems or lyrics for song festivals on Radio-Television. They often met and discussed poetry, verses. They also met in our office or in our upstairs hallway and we laughed at their world of the poet, with their concerns, which we appreciated because they made us laugh. For humor I also once tried to write the verses of a song. I titled it “I’m not jealous”. I gave it to Natasha to see too. Now it was her turn to laugh, not just for the title, for my “rehearsal”, but also for the one-kilometer-long strings that the singer or trumpeter had no lungs to carry to the end. I accepted the failure.

As we laughed to laugh so in vain with Sadiq, the regime got angry badly, unforgivably with him. In the XI Song Festival on Radio Television, the singer Tonin Tërshana performed the song “Erdh pranvera” by the well-known composer Pjetër Gaci. I do not remember who the author of the lyrics of this song was. Anyway, Sadik Bejko was the literary editor of the song lyrics of the XI Festival. The song dedicated to spring also had the verse: “Someone said spring came, but I did not believe it”. So the song had to be treated as a pamphlet against the “socialist spring”, as a call not to be deceived by an illusory, icy, flowerless and colorless spring. Sadik Bejko in 1972 also published the volume of poetry “Roots”.

After this edition the cup was filled, he could no longer be tolerated. At the age of 28 he was sentenced to disappear on an underground horizon in the Memaliaj coal mine in southern Albania, to be covered with the dust of oblivion, which was heavier than the black coal dust. He was forced to take his family, wife and newborn child to Memaliaj. The party thus extended its “warm” hand to him, giving him the opportunity to “re-educate” himself among the working class! He was banned from publishing, he was banned, even after he was “rehabilitated”, to return and live again in Tirana. After 8 years in Memaliaj Sadiku and his family move further south, in Gjirokastra.

Recalling that time, many years later, in his speech of thanksgiving when he was awarded the “Literary Scepter 2010” in Skopje, Macedonia, Sadik Bejko says he was “stuck and at work you could lose your head” , that he held himself on his feet, swayed but did not fall, locked his lips bearing the “weight of drama straight on his bones”.

In a ceremony held in April 2003 in the premises of the Central State Archive, the director of the institution, Shaban Sinani, former secretary or advisor of Ramiz Alia, Enver Hoxha’s successor, had invited on this occasion some personalities, his names who were associated with the XI Radio-Television Song Festival. Shaban Sinani had not forgotten to invite the widow of the dictator, Nexhmije Hoxha, as well as his daughter-in-law Teuta, the wife of his eldest son, Ilir. In the hall was also Sadik Bejko, who in a moment of calm, after the discussions of others ended, takes the floor and says: “I do not understand why the persecutors and the persecuted have joined in this hall! We who were exterminated for that desolate Festival, now we have to stay with the exterminator. What does Nexhmije Hoxha want here “?! He did not express any sense of revenge, only demanded that the ghosts of the black past remain in their darkness. Nobody bothers them, let others not bother”!

The ‘fate’ of Sadik Bejko, was also shared by the painter, Edi Hila!

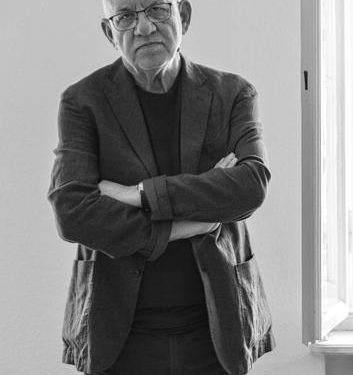

Almost the same fate as Sadiku had his peer, the painter of the Albanian Radio-Television, Edi Hila. Edin, like Sadiku, I knew very little about. He graduated as a painter at the Academy of Fine Arts in Tirana, in 1967. I believe that this year, if I am not mistaken, he started working at the Albanian Radio-Television as a scenographer. However, I remember him quite young, an educated boy, with a calm voice, almost whispering, with a childlike smile and a rather attractive portrait as in medieval or Renaissance paintings. Sometimes, in the meetings of the band, we would sit together at the end of the orchestra hall, where they also took place. I never heard him discuss, express an approving or disapproving opinion. When he asked me about something, he was very careful, somewhat lost, as if he was looking to discover a new planet, but he did not dare. Maybe he really lived in another world and what was discussed in the collective either he did not understand, or were completely foreign to him. Artists are often in such a position and Edi was a true artist in spirit and in creativity. He who in his first works managed to reveal a very individual art, rich in values and ideas, fresh and sincere.

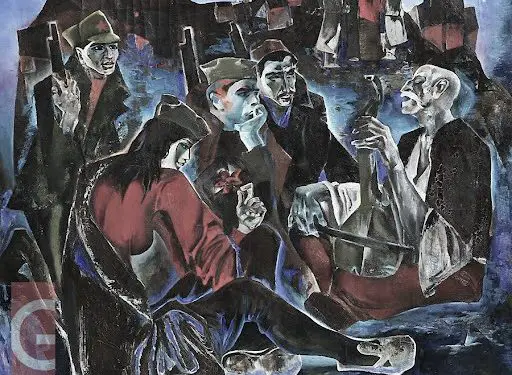

“Planting trees”, sent Hila to the poultry, while “Epic of the morning stars, Gjergon in Spaç!

In November 1971, Edi Hila exhibited the painting “Planting Trees”, while next to him, another painter, Edison Gjergo, and was represented with “The Epic of the Morning Stars”. With these works, both of these creators had dared a lot. Their colors ignited some sparks, which disturbed the darkness of the regime’s darkness. Life and dynamism, the unusual breaking of figures and objects, seemed to challenge the stifling smell of mold or rot of the existing political system. The freshness of the air brought by the paintings of Edi Hilë and Edison Gjergos, were not for the lungs exhausted by the decomposition of the totalitarian Albanian society. The feelings and concepts they conveyed were like calls to dream of the sun, they constituted heresy, crime, and therefore they had to be killed from the cell. The paradox is that initially the two painters were officially congratulated for their works, which were liked by the League of Writers and Artists of Albania, by the Party Committee of Tirana. “Planting Trees,” as Edi Hila points out, was bought, even immediately, by the National Art Gallery, but the young painter’s joy would not last long.

The monstrous class war machine, at breakneck speed, set in motion with all its gears; Plenum IV, Ministry of Internal Affairs, State Security, Party secretary, directed meeting of the collective, denigrating criticism…! Edison Gjergo ended up in the infamous Spaç prison, while Edi Hila ended up in a chicken coop. The first to be re-educated among false but also real criminals, and the second to become a chicken among chickens, to find there the inspiration for his future deeds!

Recalling that time, Edi Hila says: “It was a terrible period of arrests and convictions. I remember, one fine day, a man on a bicycle saying to me: Are you Edi Hila? Come after me. You should not talk to anyone along the way. And he took me to the Ministry of Internal Affairs. After 40 days of pressure and blackmail (my wife, Joana, was pregnant, we were waiting for Klodi), they ask me to cooperate with the State Security. I did not accept. The next day of this request I was called by the Secretary of the Party on Television. The moment was coming when, since I did not accept the cooperation, they would take action. I also remember something. In 1973, I went to Florence for a specialization from the Albanian Television. There we were accompanied by friends of the Labor Party and, apparently, we were under their control and care, as one of the accusations leveled against me, and this is very ridiculous, was: “You got in the car with the Italians.” A meeting was held on Television, where all those who were party members, communists spoke! “After that, the chief of staff took me, took me to the chicken coop, covered my throat and I worked there for three and a half years.”

We are not far from the Inquisition and El Greco in these years even though centuries had passed, even though we thought we were building the fairest, happiest society.

Edison Gjergo was released from Spaç prison in 1982 and started working as a painter in the “Teaching Tools” company. He failed to see his only daughter, who will be born three months after his death, in 1989.

Edi Hila, after serving his sentence in the chicken coop, was appointed to work in the decor of the city where he was to serve the propaganda of that time. He insisted on leaving this job which, as he himself said, caused him the same deformation and wasted the pleasure of drawing.

After the ’90s, Edi Hila opens painting exhibitions around the world!

Eddie returned to where he belonged in 1991. In that year, those who denied God to take his place had ended up in hell or were rushing to seek political asylum at his door. This year he began teaching at the Faculty of Visual Arts and two years later became its dean. It seems as if he is in a hurry to reach the lost years, to find the space and appreciation that was denied to him. Edi will thus open one personal exhibition after another at the National Gallery of Art in Tirana, at the Aud Gallery in Berlin, in Karlsruhe, in Paris, in Brussels, in Florence, etc. His works have been awarded several times with first or second prizes in the editions of the international competition “Onufri”.

By chance I came across a photo of Edi Hilë online. The years had left their mark. When you see your peers or relatives after almost half a century, when you see how their portrait has changed, you understand the changes that have taken place in the meantime in yourself. Edi with black hair, beautifully combed, was now Edi with gray hair, even without hair because he was shaved to zero. It was with the same smile as before, but somewhat sadder. The glasses showed that even his gaze was not that of the past, of youth locked in a cage like poultry chickens. In the Albanian press he reads that “already Hila’s characters do not have concrete characteristics, they are distant, haunted, tired, lying, without energy. An exhausted, sleepy, passive crowd. The colors are gone and the gray has conquered the world … “! Does his work reflect Edin himself?

Edi Hila, as once in the dictatorship, continues to speak to us today with his painting, regardless of the colors and tools he chooses. As he spoke yesterday, he also speaks about Albania today. His works tell us that the ghosts of totalitarianism are deeply ingrained in our consciousness and in our lives, that the psychological and moral trauma caused by communism to the country is present, lives among us, that Albanian life with its perversion competes quite successfully with the most fragments absurdities of Kosturica films. Today, Edi wants to remind Albanians that they live in a reality, where the demons of the past are still like heavy bullets in our feet to make us tired, to make us tired.

The dictatorship hit the painter Çlirim Ceka hard!

Another painter, who was hit hard at this time by the dictatorship, was also Çlirim Ceka. I met him during the military exercises we did together in ward 1105 near the Beshir Bridge on the outskirts of Tirana, on average 2 days every month. Liberation had finished his studies at the Higher Institute of Arts for painting and had started working initially as a figurative specialist in the only Publishing House “Naim Frashëri”. Then, until 1975 he worked as a lecturer at the Higher Institute of Arts.

Outside of the days of flight or military service, with the Liberation we were rarely seen. I remember a chance meeting on “Qemal Stafa” street, near the 8-year school “Fan Noli”. He was heading to a shoe repair shop. He asked me to accompany him. During those subways we did together, he told me that in this shop he would beg a shoemaker to sell him some small rivets he needed for picture frames. There were no such rivets on sale in the market. Only shoes were supplied, but not for sale. When we got into the shoe store, I saw that Liberation was afraid to ask if anyone could sell him a handful of rivets. I freed him from this “trouble” and I asked the question. The cobbler, after we also explained to him why we needed the nails, did not extend it, filled a fist with them, gave it to us nor refused to take the money we proposed. When we went out on the street, Liberation told me: “For another I would have done it, but for myself I cannot, I can hardly.” “I, too,” I said with a laugh, “would not have done it for myself, but I did it for you, even though the cobbler does not know that I did not do it for myself.” Memorie.al

The next issue follows