From Kolec Topalli

Memorie.al / Class war and communist persecution, acted on all layers of society. They were very harsh, especially among intellectuals who were educated abroad and had western culture. The communist regime’s fear of democratic intellectuals, who could think differently from official dogmas, resulted in their persecution, arrests, internments, torture and shootings, which cut off the spiritual and cultural ties of Albanians with the western civilized world for half a century. . The following examples clearly speak of this.

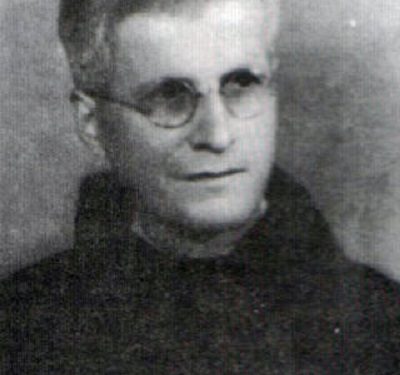

Bernardin Palaj and Donat Kurti gave cultural treasures to our nation. The first was the most prominent Albanian mythologist, called by the linguist Desnickaja “the best connoisseur of our mountains”, poet and prose writer. Laureate in Innsbruck, Austria, professor of Greek and Latin at the “Illyricum” Lyceum, imprisoned in 1924, as an opponent of the Monarchy, devoted his whole life to Albanianology.

After the announcement given by Shtjefën Gjeçovi in 1905 that “a priceless treasure of the Albanian epic is hidden among our mountains”, he together with Donat Kurti tracked down, collected, systematized and published hundreds of Kreshnik songs, which were published in the magazine “Hylli i Light”, which was valued as the best in the Balkans. And the reward he received for this gigantic work was his imprisonment in 1946, the most inhumane torture until he died in prison at the age of 50. One of his fellow sufferers testifies: “They had tied his hands with rusty wire to the pine tree in the yard, where he was suspended, where the prisoners were tied after they were beaten to death.

Then they left him stuck under the stairs in a stinking place. And this lasted for months and months, until his blood was poisoned and he died of tetanus. They buried him at the end of the yard, but his remains were never found.” He died accused of being an agent of foreigners, the one who had donated his most expensive visaras to the nation, which foreign scholars have compared with the greatest epics of Europe, with the “Iliad” of the Greeks, “The Songs of Roland” ” of the French and “Nibelungen” of the Germans.

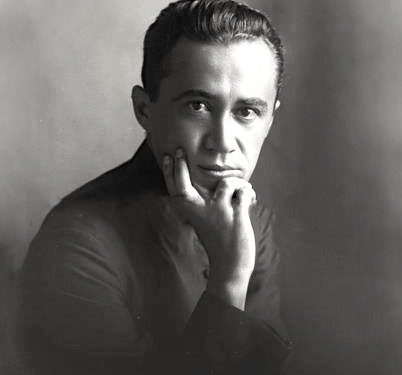

Donat Kurti, who was a diligent collector of folklore, called; “Albanian Andersen”. Graduated from the “San Antonio” University of Rome, where he was awarded the title of “Doctor of Science”, excellent connoisseur of 7 foreign languages, he was praised by Norbert Jokli, “among the greatest Albanian prose writers”. But he too had the same fate as his accomplice. Imprisoned in the first years of the establishment of the dictatorship, he was sentenced to death, a sentence that was later changed to life imprisonment. And spent 17 years in communist prisons and extermination camps. The irony of fate wanted him to die forgotten, alone and in complete silence, precisely on the days when a symposium on the Kreshnik cycle was being held in Tirana.

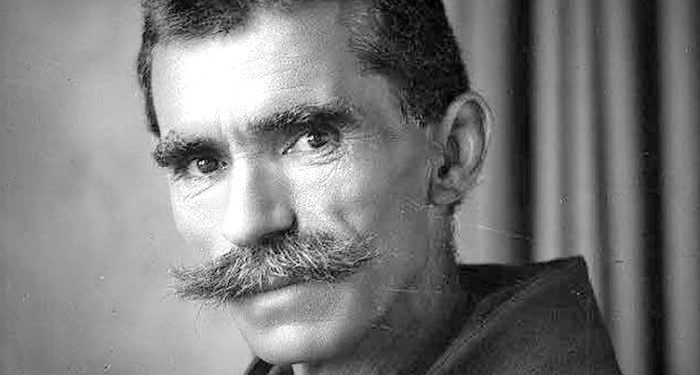

Another Albanianologist had an even worse fate. Lazar Shantoja, who was a folklore collector, publicist, literary critic, poet and prose writer, talented translator of Goethe, Schiller and Heine. But the one who, for the protection of democracy, had tried prison since the 20s, the one who talked for days and months with Wilhelm Tel’s Faust, suffered badly from the dictatorship. Arrested in February 1945, he was tortured so much that he begged God to save him with his death. When her mother saw her for the last time, crawling behind bars with gangrenous legs, she begged the guards to kill her, so she wouldn’t suffer anymore. And they shot him after a farcical trial, which gave him the death penalty.

The last person who saw his murdered body testifies: “They had torn him apart. He had a crippled leg and arm. They had preyed on him with a saw. The right thigh was extremely swollen, it seemed larger than the body, and everywhere there were traces of wounds inflicted with all kinds of tools. There were no coins in his leg and he had been shot with a volley of bullets inside the grave. Stones and dirt covered his mutilated body, so that his grave would never be found”. His work, distributed in magazines and newspapers of the time, was published in a volume of about 700 pages, 60 years after the death of the author. Appreciated beyond the borders of Albania, I had the opportunity to be present in Rome, four years ago, when he was commemorated with special honor in a scientific conference, specially organized for him.

Another scientist, intellectual-Albanologist, who was killed by the dictatorship in the first days of the establishment of communist terror, was Nikollë Gazulli. He has left the best provincial dictionary of rare words, with various explanations and clarifications and with a wide overview of Albanian prefixes and suffixes, which make it an invaluable treasure in the field of lexicography.

He was also a pioneer in the field of onomastic lexicography, publishing the first Albanian “onomastic dictionary” in the magazine “Hylli i Dritė”, where historical and ethnographic problems are also addressed. From the information we have, he had collected another 2,000 words, the fate of which is unknown. And despite all these contributions, his name was never mentioned in Albanian studies.

Mostly it was allowed to cite only the title of the work with abbreviations, but never its author. And this happened because he was shot without trial, in the first years of the establishment of the communist regime. Surrounded by communist gangs, he was killed as a martyr in a cave where he had taken refuge, to hide from the red terror, a Bajram Curr, of our times, who was also left without a grave, the one who in the fight for democracy in the years 30, had suffered 4 years in Gjirokastra prison and was released thanks to the intervention of Norbert Jokli, Gjergj Fishta and Aleksandër Xhuvani.

Mark Dushi, who was another diligent collector of folklore, rare lexicon, toponyms, historical, mythological data, legends, etc. He left several works in manuscript, which are kept in the State Archives and are waiting for a careful hand to bring them to light. A monograph of his, which was published as a posthumous work, “Tirana and its surroundings”, contains archaeological, ethnological, linguistic and etymological data and arguments of scientific interest to know the capital and its surroundings. And the reward for all this work was his imprisonment by the dictatorship, cruel torture, death sentence and shooting at the age of 46.

Many other scholars also had the same fate, who was rewarded for their work with prisons, exiles and other persecutions. Such is the case of three prominent orientalists: Mykerem Janina, Vexhi Buharaja and Tahir Dizdari, all three very good connoisseurs of western and eastern languages, old and new, philologists, translators and transcribers of many works of scientific value and literary.

Mykerem Janina, who was among the best specialists in Ottoman, a perfect connoisseur of historical documents and paleography, translator of the “Book of the Albanian Sanjak” of the Turkish historian Inalçik. He started his publishing activity in the 30s, but was imprisoned twice during his life, with the stereotypical charge of “agitation and propaganda”. He spent about 15 years in prisons and exiles. In the second imprisonment, he was close to 80 years old.

Vexhi Buharaja, has left a very large volume of Ottoman documentary materials, which are of first-hand importance, for the study of the history of Albania.

By translating them into the Albanian language, he brought to us the works of the brothers, “Besa” of Sami and “Dreams” of Naim, as well as some world masterpieces of Persian poets. But this intellectual with great scientific potential, who worked for 10 years at the Institute of History, was fired in 1975, to spend the years of greatest scientific maturity in complete solitude, away from any scientific activity.

Tahir Dizdari is the author of the largest and best dictionary of orientalisms in the Albanian language, where numerous explanations are given for Turkish borrowings, with lexical and grammatical, ethnological, literary and etymological arguments, and with comparisons with other languages of the Peninsula. Balkan, which makes it invaluable not only for Albanian studies, but also for Oriental studies and Balkan studies? But all this painstaking work, for which he worked all his life, was not published while the author was alive, and did not see the light of day 33 years after his death. And this for the simple reason that Tahir Dizdari was imprisoned in 1951, as an anti-communist, who was exiled by fascism in 1939 for his patriotic and democratic feelings.

Hellenists, Latinists and other translators also had such a fate, whose only fault was that they had studied in Western schools and did not agree with the dictatorship. Guljelm Deda, who made Ludovico Ariosto’s “Mad Orlando” speak Albanian, spent his whole life in prisons and exiles, the one who for 17 years worked to translate 40,000 rhyming verses into the Albanian language. Even when he was released, there was no other work for him than to break stones on the mountain of Taraboshi. Mark Dema, the talented translator of Virgil’s “Aeneid” also had this fate; Veniamin Dashi, translator of many works of Albanian nature, by German researchers.

Even these were rewarded with many years in prison and eternal anonymity. Mithat Araniti, translated from German the capital work for Albanianology. Such is the Etymological Dictionary of Indo-European languages, with three volumes by world-class etymologists, Alois Walde and Julius Pokorny, a copy of which is in the Durres Museum. And the reward for this work was the endless years of prison and exile.

Another deep connoisseur and translator of classical literature, Gjon Shllaku, pronounced world masterpieces: Homer’s “Iliad”, the works of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, Virgil’s “Georgicas” and “Songs of Roland” of the French epic. He left the “Latin-Albanian Dictionary” and the “Greek-Albanian Dictionary” in manuscript. For all this, he was awarded several years in prison.

Nikollë Dakaj, a talented translator, linguist, poet, literary critic and folklorist, after spending several years in communist prisons, was forced to earn a living by working in the brick factory, where among the pits of mud, you could find the most cultured people of the time, because this was the place designated by the dictatorship for those who met with Homer and Virgil, with Dante and Petrarch, for those who were educated in west and tried to go against the official trend.

Another talented translator, Mark Harapi, who gave us Manzoni’s masterpiece “The Betrothed” in Albanian, one of the most cultured intellectuals of the time, who had refused to stay to teach at the University of Rome, only to returned to the homeland. He was the first to transcribe Bogdan’s work “Cuneus prophetarum”, equipping it with many comments and linguistic notes. And the reward for this work was a sentence of 20 years in political prison, of which he served 10 and after that another 5 years of exile. Until he died, he lived on the alms of the benefactors of the street where he lived.

This fate also happened to the last classic of the tradition of Greek-Latin translations, which left us a few years ago. Pashko Gjeçi translated about 40 thousand verses from classical and modern languages, giving us in a pure and rich Albanian “Odyssey” by Homer, “Faust” by Goethe, “Hamlet” by Shakespeare, “Andromache” by Rasin, the poems of The Leopard of Karduçi, and above all the “Divine Comedy” trilogy, to which he devoted 20 years of his life.

And as a reward, he was imprisoned in the first years of the establishment of the dictatorship, suffering for several years in the terrible communist prisons and extermination camps, where at the entrance it could be written as in the gates of Dante’s hell: “This is where you pass in the city of misery / Here you pass into boundless pain / Here you pass to the people you lose your sight / O you who enter, you are finished”. And many who entered these prisons, did not come out alive, but died in the prisons of Burrel and Spaç, or the swamps of Maliq and Beden.

The talented French translator, Isuf Vrioni, also spent a good part of his life in the prisons of the dictatorship. He who made the French themselves his own with his translations into an elegant French, spent 16 years in prisons and extermination camps, and when he came out, he left his name in prison, which could not be written in any book, magazine a newspaper. He was a life sentence even when he was released from the small prison to the big prison. He remained anonymous until the 90s.

Another example of this persecution is Frano Illia, this second Shtjefën Gjeçov, who paid for his passion for collecting docks, customs, traditions and rare words of Albanian with a real ordeal of endless suffering, because then when in 1967, he submitted to publish “The Canon of Skanderbeg”, they called him, not to publish his work, but to handcuff him and after 7 months of torture in the cells of the State Security, with a farcical trial , where there was no lack of applause, they sentenced him to death, a sentence that was returned to 25 years in prison, of which he served 20 years.

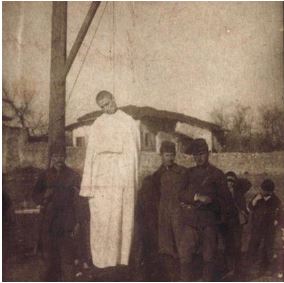

Gjergj Fishta, the great of Albanian letters, called “Albanian Homer”, the chairman of the alphabet drafting commission, one of the founders of the “Literary Commission”, was saved from the communist hell by premature death. But he could not be forgotten so easily, because his work, published during the poet’s lifetime, was known and recited by Albanians from North to South. Here’s why he was a potential danger to the dictatorship. Therefore, even dead, he did not escape the cruel persecution and macabre communist revenge: his remains were discovered, taken out of the grave and thrown into the river Drin.

In every country of the world, the last resting places of national poets are fanatically preserved as holy relics and as places of honor and pilgrimage. Dante’s tomb, preserved in Ravenna, for nearly 700 years; Shakespeare’s grave has been preserved in Stratford for 400 years. Even De Rada’s grave has been preserved in Maki of Kozenza for more than a century by the people of Arbëresh, who were lucky enough not to live the communist hell. Only in the Albania of the communist dictatorship, a national poet is left without a grave. It has been said that the great men of this nation should not rest in peace after death, but their bones should be taken out of the grave by foreigners to turn them into talismans; and from the Albanians themselves, to throw them into the river. And what they couldn’t do to him while he was alive, they did with his work.

It was forbidden to read, to comment on, to keep at home. Many cases are known when arrested intellectuals have been accused of having read Fishta, of talking about it, of hiding “Lahuta” and many other accusations of this nature. The state of the Slavic-communist dictatorship could never forgive the great poet, the anthem of the war that the Albanians did “don’t divide the lands of Albania, to fill the cliches of Russia”. While as the chairman of the commission for drafting the Albanian alphabet, he was never mentioned and because of him and any other anathematized member, the photo of the commission of this congress never became known during the 50 years.

Viktor Volaj, linguist lexicologist, professor of Albanian, Latin and Greek at the “Illyricum” high school in Shkodra, spent many years in internment camps. He was the best commentator and explainer of Fishta’s works, for which he worked for many years under the supervision of the great poet. He was also the author of several other works, which were lost in the years of the dictatorship without being able to see the light of publication. That’s why he was called “the great academic without works”. At the instigation of Xhuvan and Çabej, he had collected and submitted to the Institute of Linguistics, 1,200 rare Albanian words and expressions, as a contribution to the “Big Albanian Dictionary”, but his name is not mentioned anywhere.

Nikollë Mazreku, this good connoisseur of history, language and literature, one of the most excellent Latinists, left many manuscripts, among which a volume about the national hero, Skënderbeu. He has collected many rare words, which he has masterfully used in his poetic verses. An ardent defender of the Albanian race and culture, he wrote under the pseudonym “Nikë Barcolla”, the famous pamphlet against the Cordignano scandal. For all his merits, the dictatorship rewarded him with 25 years in prison and 12 years in exile.

Marin Sirdani, historian, folklorist and writer, passionate collector of legends, songs and legends, tracer of rare words and toponyms, author of works; “Skanderbeg according to oral tradition”, “For national history”, “Albanian Albania”, etc. He had left several thousand pages in manuscript, during a period of 50 years of tireless work, but they were burned and disappeared by the criminals of the State Security.

His brother, Aleksandër Sirdani, another collector and researcher of Albanian folklore and rare words, who has left thousands of manuscript pages, was tortured in the most inhumane ways and his body crushed by torture was taken around Koplik, to ‘introduced to receive the citizens. Then they killed him by piercing his body with a pitchfork, until they rolled him into a black hole.

Other scholars were left in silence; their work was not appreciated or published. The great linguist Selman Riza, who dedicated his whole life to Albanianology, had this fate. The one who was exiled in Ventotena by fascism, for his democratic ideas in defense of the country’s freedom, the one who was exiled by the Yugoslav Titist regime, for his efforts for a free Kosovo, the one who changed prisons and internment camps, yes as well as places of work and residence, he was brutally persecuted by the communist dictatorship of Tirana: he was expelled from the Institute of Linguistics and, interned in Berat. And just as his unpublished work was left in silence for years, so was the day of the burial of this colossus of Albanianology.

Linguist Justin Rrota also had such a fate. For the author of so many studies in the field of linguistics, for the scholar who brought to our country the first work written in the Albanian language, “Meshari” by Gjon Buzuku, no one was remembered by the officials of the regime, therefore his death passed in silence, just as his work, which had a 50-year lethargic sleep in the Archives of the Institute of Linguistics, was left to wake up and see the light of publication, only after the overthrow of the dictatorship and the establishment of democracy.

For 50 years in a row, the names and scientific works of the most prominent personalities of the diaspora were covered with silence: Martin Camaj, Namik Resuli, Arshi Pipa, Karl Gurakuqi, Mustafa Kruja, Tajar Zavalani, Zef Valentini and many other albanologists, the names which had become taboo in the communist regime.

Martin Camaj is one of the most prominent albanologists, moreover a writer and poet, among the most talented. In the field of Albanianology, he left a series of works on the history of the Albanian language, on grammar and dialectology, on etymology and Arbëresh dialects, on old texts, folklore and literature. He was a pillar of emigration, who kept alive the study of the Albanian language and the Albanian tradition in Italy, Germany and wherever he went.

Nevertheless, he received the epithet “traitor” from the totalitarian regime, because he was able to escape from the communist hell and go out into the free world, remaining a true Albanian all his life. Even after death he remained so. I had the opportunity to visit his grave. It is the simplest in the cemetery of Lengriesa in Germany: a piece of uncarved rock, which his compatriots had brought from the mountains of Dukagjin, to put on the head of this great Albanian, who died in a foreign land, unable to to visit his homeland even once.

Another albanologist who was able to escape from Albania surrounded by barbed wire and go out into the free world was Arshi Pipa, language and folklore researcher, literary critic, esthete, poet and translator. Arrested immediately after the establishment of communism, he was able to escape after his release from prison. A university professor in the United States of America, where he emigrated, he directed several scientific and literary magazines and published several valuable books and articles about Albanian culture; but his name until the 90s could not be mentioned, and all his publications remained unknown.

Namik Resuli, who was a philologist, grammarian, historian of literature, researcher of old texts, director of the Institute of Albanian Studies at “La Sapienza” University of Rome. He has transcribed De Rada’s “Songs of Milosao” and other works of old and Arbëresh literature. The “Albanian Grammar” he wrote is one of the best of its kind.

But his greatest work was devoted to the transcription, commentary and publication of the earliest work written in the Albanian language, Buzuku’s “Meshari”, with which many scholars from different countries worked for years, even after its publication 10 years later by Eqrem Çabej, whose work remained locked in the archives of the Institute of Linguistics, described as “a work with religious content”.

The most recent example of this is the 800-page work “Das albanische Verbalsystem in der Sprache des Gjon Buzuku”, published in 2004 by the academician Wilfried Fiedler, who relied on Namik Resuli’s publication. And with all these great values for Albanianology, his name remained taboo, and his work was condemned for 50 years with the letter “R”, which means “reserves”. He was never allowed to set foot in the homeland.

Another outstanding Albanianologist, whose work was never appreciated in the totalitarian regime, was Zef Valentini, Albanian by heart and soul, although not by nationality. He was a historian, ethnologist, linguist, professor of literature, collaborator and director of scientific and literary magazines in Albania and abroad, member of several academies. An excellent connoisseur of the Albanian language, history and ethnology, he was an ardent defender of the Albanian race and the cultural values of our people before the civilized world and a point of reference for Albanian studies.

Even when he left Albania, he continued his studies and publications in the field of Albanianology, working at the University of Palermo and directing the International Institute of Albanian Studies. He worked for an entire institute. His major work “Acta Albaniae Veneta”, contains 27 volumes, with documents on the medieval history of Albania.

And while he gave his life for our country, never during the 50 years of dictatorship, he could step on it. His name had become taboo and no one could refer to him. And what the communist regime failed to do to this scholar, who left Albania a year before the establishment of the dictatorship, it did to his work, which remained in prison for 50 years, also condemned with the letter ‘ R’.

And at the end of these lines, I ask the question: “What was the fault of all these”? Their fault was the same as mine, when the communist dictatorship at the age of 10, in 1949, interned me in extermination camps with barbed wire, in Turan and Bênçe in Tepelena and in Ali Pasha’s castle in Porto-Palermo in Himara.

Their fault was the same as mine, when in 1990, while I was a village teacher, far from my family; the State Security had put my name on the black lists of death, published after the victory of democracy. People who forget their history condemn themselves by repeating it. Let’s not forget the national tragedy of 50 years of communism, of the martyrdom, crucifixion and torture of an entire people. Memorie.al

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)