By Shkëlqim Abazi

Part twenty

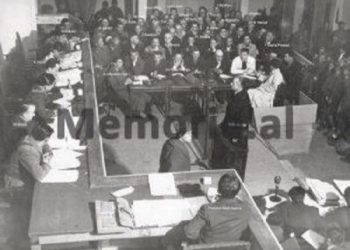

Memorie.al / I were born on 23.12.1951, in the black month, of the time of mourning, under the blackest communist regime. On September 23, 1968, the sadistic chief investigator, Llambi Gegeni, the vile investigator Shyqyri Çoku, and the brutal prosecutor, Thoma Tutulani, massacred me at the Department of Internal Affairs in Shkodra, they split my head open, blinded one of my eyes, deafened one of my ears, after they broke several of my ribs, half of my molars, and the thumb of my left hand. On October 23, 1968, they took me to court, where the miserable Faik Minarolli gave me a ten-year political prison sentence. After half of my sentence was cut, because I was still a minor, sixteen years old, on November 23, 1968, they took me to the political camp of Rreps and from there, on September 23, 1970, to the Spaç camp, where on May 23, 1973, in the revolt of the political prisoners, four martyrs were sentenced to death and executed by firing squad: Pal Zefi, Skënder Daja, Hajri Pashaj, and Dervish Bejko.

On June 23, 2013, the Democratic Party lost the elections, a perfectly normal process in the democracy we claim to have. But on October 23, 2013, the Director General of the reborn government sent order no. 2203, dated 23.10.2013, for; The dismissal of a police officer. So Divine Providence was intertwined with the neo-communist rebirth Providence and, precisely on the 23rd, I was replaced by none other than the former operative of the Burrel Prison Security. What could be more significant than that?! The former political prisoner is replaced by the former persecutor!

The Author

SHKËLQIM ABAZI

Continued from the previous issue

RREPSI

(Forced Labor Camp)

Memoir

I was assigned to the electricians’ group. In fact, only one of them was a real electrician, Gaqkë from Korça, because the other one, Maqua, was a former driver. So, with me, we completed the group of three, which, depending on the workload, could be increased or decreased as needed. But for the moment, that’s all we were. I was taken there more as a favor and as a minor, of course with the desire and support of Brigadier Velko, as a friend of my friends. On the first morning, as soon as we entered our section, in a tall and long rough building, divided into several annexes where other craftsmen also carried out their activities, I met my group mates.

Although I had met Gaqo the night before, now that we had found our place and sat down in front of a glowing resistor, laid out on a sheet of eternit, we started to talk. Gaqka asked me why and for how long I had been sentenced, and I answered him briefly. (After each answer, he expressed surprise at everything he heard; it seemed he couldn’t believe that they could politically sentence even a minor. At the end of each sentence, he would let out exclamations of amazement, such as: “Uha-a-a!, what’s this-s-s!, no way! man, man!, they do this too!, where-e-e, man, man-n-n”!, etc.)

The days that I was in the camp with a medical report, the old men instructed me on how I should behave and talk to different people, especially strangers. They taught me that the best way was to give laconic answers, without getting into comments. (“Speak directly, boy, without going into long explanations! Time itself will teach you who you’ve met, one by one! Didn’t I tell you that here, they are all professors? And you, you will become one too!” – old man Esheref encouraged me when this topic came up.) So, well-instructed, I answered the questions they asked me briefly and accurately, without going into details. The first week passed without any memorable mishaps, apart from the problems of adapting to the work. But how did such a day begin and end? Every morning, we woke up at the same hour, at five. Early on, the daily commotion would start; that is: the shouts of the town crier, which would drive you crazy, and the snake-like whistles of the police, which would tear your ears.

Whoever was at work had to get up quickly, throw a jacket over their shoulders, and hurry to the bathrooms? In the latrine, the line was the most boring ritual that became a problem in itself. As soon as you finished your personal need, you would run to the faucets, splash two handfuls of water on your eyes, take the bowl in your hand, and head straight to the soup cauldron. Even there you would wait in line, no matter how disgusting that broth was, it remained the only source that kept us alive, so whether you wanted to or not, you had to eat it. After you had sipped that slop, you would hurry to the barrack to throw something thicker over your shoulders, and finally you would end up in line for work.

In Reps, the winter was harsh; the cold was intensified by the wind that blew non-stop, day and night. Not to mention when it was cold, the frost and humidity would penetrate to your bones. Experience and necessity had forced the convicts to adapt clothing that under normal conditions, no stylist, in any corner of the globe, would ever think of. With the thin canvas jackets, they had fashioned a kind of overcoat with a hood. Dipped in linseed oil, they replaced the oilskin and protected you quite well from the wind and rain. The luckiest ones, depending on the opportunity or chance, had also put a layer of oil paint or enamel on top and felt more comfortable.

So, as they threw this kind of “overcoat” over their shoulders, the convicts would line up in the alley that connected the two camps. There, like some puppets that are set in motion by some invisible strings, each one took his place. They lined up according to the brigades and waited for the work police to take them over. Usually, the work guards stood outside the gate, on the inner side of the construction site, but sometimes they would come in on this side. Then they would push us violently towards the work fronts and the clanging of the clubs on our backs would begin woe to anyone who had the misfortune to fall into their hands.

But it happened that the work police could not arrive on time, because they lived in distant villages and the lack of means of transport did not allow them to catch the schedule. Thus, they would show up directly at work. At least we would escape the club that day. But these pleasant cases were sporadic. Only at the work site could you break away from the herd. There, each one would head to the previously determined front. In the groups of three, you felt a little freer, because everyone knew their partner. Being part of such a group, you got a feeling of freedom, both in communication and for mutual understanding.

Even people with health problems felt some relief. The strongest ones helped the weak and the sick to meet the norm, because not meeting it was severely punished, with tying to electrical poles with copper wire and then you would have to spend whole days in isolation in the camp’s dungeons. All day long, you would toil at work, until the hour of the bell came. Around four o’clock, when the bell rang to signal the end of a workday, we felt exhausted. However, the duration was not fixed, but varied depending on the mood of the police and the work foremen.

Only after the bell, each one with their tools on their shoulder, could they head to the wooden barracks covered with tar paper, hand over the tools to the warehouse manager, and quickly line up on a flat strip, about seventy meters long and four wide, which they had nicknamed “The Road of Golgotha”, because of the torments and horrors we had to overcome from time to time. Here, everyone had to join the brigade, but, before entering the line, everyone had to check themselves. Only when you were sure that no forbidden item was stuck in your pocket, would you take your place.

But what were the forbidden items?! Nothing more than the ordinary. As a rule, they classified everything that could be used as a piercing or cutting tool as forbidden. The “forbidden items,” which should have been precisely defined by the internal regulations of prisons and correctional institutions, were often left vague, so it was up to the police to define them according to their whims. Thus, it was up to the police to judge whether to allow or forbid a certain item to enter the sleeping camp. So, it was he who forbade and allowed, or in the language of the people, he was; “both judge and jury”. Anyway, the method of classifying allowed or forbidden items, unspecified in any regulation, left abusive loopholes even among the police themselves. What one would allow today, another would forbid tomorrow, and vice versa. Ultimately, according to the whims of the police, anyone could spend the night in the dungeon.

This had made the instincts of the prisoners sharpen to the highest degree. To name the items according to the character of the police, into “evil-spirited” items, with a pronounced dangerousness, and “good-faced” items, those that were less harmful. So, according to the police on duty, the items could be “reactionary,” which would lead you straight to the dungeon, and “blameless.” And at most, they might throw it away, but you would get away with it. For example, a piece of wire would lead you to the dungeon, some firewood might be confiscated for the kitchen of the barracks, but in the end, it would end with a simple reprimand.

Then, it was time for the count. A very insulting act, which reminded you of the sheep pen. Everyone with their hats in their hands, necessarily in a line of two, had to pass the checkpoint, like children in kindergarten. But it happened by chance that the number didn’t come out, and then they would start all over again. This multiplied the torture. After a tiring day, when you could barely wait to get into the camp, to kill some of the terrible hunger, which was never quenched, they would force you to stand for several more hours, in the wind, rain, snow, or heat. When the moment came to get to the soup cauldron, depending on the season, in winter you would get leaks with pieces of rotten meat. And in the summer, pieces of blackened eggplant, along with dead flies. After all that I described above, it is understandable that free time was very limited.

On the very first day, they equipped me with the tools of the trade. While I was waiting to get the electrician’s pliers and screwdriver, they gave me a wedge-shaped chisel, a hammer the size of a sledgehammer, a pickaxe, and a shovel. Then, master Gaqka marked some lines with chalk on the wall and some marks with the tip of the chisel on the floor, and ordered me to perform my professional duty, that is, to break the concrete of the floor or the plaster of the walls. Anyway, I tried to do it as best as I could, even though the heavy hammer and the chisel with its worn edge, made my hands bleed. I had to wrap my fingers with old rags, which I heard them call; “straxhio”. After a week or so, I met the other members of the brigade, because at least twice a day, we had to line up together for roll call; both when we went out and when we came back.

Gaqo “the Town Crier” or master Gaqka, as everyone called him, was a man around fifty years old, with a slightly plump body, always smiling, where a series of crooked, rotten, and sparse teeth stood out. A few fallen hairs came to a point on his wide forehead. He was a specialist electrician; he had learned the trade with the Italians, in the workshop of “Birra Korça.” He had worked on all the works built in Korça, from the Sugar Factory in Maliq to the mines of the district. Raised in the environment of Korça craftsmen, as a minor he had been infected with communist ideas and during the war years, he had been involved in illegal activities in the city and its surroundings.

As long as his childhood friends and those of the years of illegality were in leadership positions, Gaqka also felt completely comfortable. The communists considered him a valuable friend, they had awarded him the “Order of Freedom of the First Class,” they had decorated him with the Medal of the “Hero of Socialist Labor” and with the “Worker Vanguard” Order, who worked for the next millennium. As soon as his close friend, Koço Tashko, fell from “power,” no one needed Gaqka anymore. Thus, the burden fell on him. He started rambling here and talking badly there and he stepped on the regime’s toes.

This is what the Sigurimi people were waiting for; to fabricate a group, supposedly with sabotage intentions, and they catapulted Gaqka as the leader. After a judicial farce, with false witnesses, and also with the confessions of the protagonists themselves, for uncommitted and never-thought-of crimes, of course obtained with beatings, they gave him a capital punishment, death by firing squad, which after the appeal, they changed to twenty-five years in prison and finally, they brought him to Reps, where craftsmen were needed. As a person, he was kind-hearted, but even though they couldn’t do much more to him, he felt under permanent blackmail and panics from the spies. As long as he felt free, he was cheerful and kind, but as soon as he faced even a small pressure, he would frown and close himself in his shell from terror. He was afraid of losing his job, so under the effect of terror, even though he wanted to protect me, he encouraged me to be more diligent and obedient.

As for Maqua, whose real name was Thoma Çoma, he was a skinny man, around his thirties, from the villages of Lunxheri. It was said that he had been a soldier-driver, with Lym Keta. He managed to survive the accident, where his colonel lost his life. Since he knew many facts about how they had fabricated the accident, for the elimination of the colonel unwanted by the high leadership of the Party, as a harmful witness, his mouth had to be shut. He ended up in prison, supposedly because he had dared to say, supposedly; “they set a trap for Lymi to kill him”! How true this legend was, had little importance, they sentenced him as an enemy, for agitation and propaganda. He ate a twenty-year sentence and the poor Thoma, was waiting for the indulgence of the Party, to pardon the rest of his sentence, but they never pardoned him, until the day he completed it to the last bit.

Although as a person, he was not bad either, his fellow sufferers considered him a collaborator of the command and no one spoke openly with him. But I, who worked with him for about two months and had the chance to get to know him up close, think that he was a deceived unfortunate man, but never a zealous informant. This opinion was reinforced even more, when after many, many years, now an immigrant in Greece, I heard the legends that his fellow villagers told. Those weeks we spent together, I avoided harmful conversations, but he was so smart that he understood that I was influenced by my friends. Without asking for an explanation, one day, he told me: “I know they haven’t spoken well of me, just as I know they have many reasons to speak badly. But I swear on the soul of my parents, who grave I don’t even knows, that I have never harmed anyone, on the contrary, I have tried to protect them. I am not a spy, like the others, although they consider me one!”

And a day later, he told me about his life: “I am an orphan, raised by charity! When they drafted me into the army, some of my distant cousins, who had been placed in good jobs in Tirana, intervened and sent me to the drivers’ course. When I got my license, they intervened again and placed me as a driver with Myslym Keta. In a short time, I became friends with him and his family. I became like a son to the house, so much so that the colonel didn’t move without me, not even to the toilet, as they say. I believe you understand how much of an insider I became? When the accident happened, to be honest, I don’t remember how the event unfolded, but I say with conviction, that it was fabricated. They couldn’t stand Lymi, because he was the most famous, the most capable, and the most sought after by the women of the Political Bureau. I knew these things, because as I told you, he didn’t move a meter without me, and the others, no doubt, knew very well that I was aware of all the adventures of my colonel.

So I think and will always think that everything that happened was not an accident, but a well-prepared plan down to the details, for the elimination of the colonel, and also for me, even though I was innocent. See these marks on my face? And if you look at my body, I am stitched all over, as if with patches!” – As he lifted his shirt, he revealed his stomach and back. On his body, I saw dozens of scars, testimony left by large wounds, and on his face, he had deep marks.

“When the car was destroyed, they pulled us out almost in pieces from under the sheet metal. They took us to the morgue, corpses. But God wanted it that the forensic doctor, who was going to perform the autopsy and fill out the death certificates, was a villager of ours. He noticed that I still had signs of life and from the morgue, he took me to the surgery room, where after complicated operations, I had the chance to survive. I consider my salvation from the clutches of death a challenge for the doctors, even though they used me as a guinea pig, but in the end, life triumphed over death and I am alive today.

I knew what was waiting for me, I would have been better off dead with my colonel! I would have been either a hero like him, or forgotten like me, but at least I wouldn’t have suffered in prison! When they saw that I was alive and that in the future I could pose a danger by talking about their deeds and the colonel’s, whom I want to emphasize were not few, the directors of this horror scenario took preventive measures, they put me in prison, with the accusation of murdering Lymi. Normally, this accusation was discrediting for them, because after his death, his family members took even more care to save me, because as I told you, I had become like a son of the house. So, they changed the accusation, from intentional murder to negligent homicide, and when even this did not work, to agitation against the Party and high State personalities.

I did everything to defend myself, I presented them with facts of unlimited loyalty, but they didn’t listen. They had made their plans. Meanwhile, they promised me that they would get me out of prison and send me on a mission abroad, to penetrate the ranks of the Albanian political emigration. I agreed to cooperate. The legend presupposed that after the sentence, they would create an alibi for me, with a possible escape from prison. According to the scenario, this would give me credibility for the foreign intelligence agencies. They asked me for a declaration of cooperation with the Sigurimi, which I signed and accepted unconditionally. I also accepted, according to their legend that I had agitated against the Party and the people’s power. They took me to a closed-door trial, where I accepted without hesitation everything that was said there, they gave me a twenty-year sentence, and here we are together now. But the harm was done; now I am called a Sigurimi spy, without having made any denunciation and without having cooperated for a second with anyone!”

After this confession, he fell silent. Drops of sweat covered his forehead and dripped down the marks of the scars from the accident. I didn’t know what to say to him to relieve him, because at that time I really thought that he was a spy and I couldn’t trust him. The idea of a possible provocation gnawed at me, or the desire to make me his friend. Much later, when the ashes on the physical, moral, and material ruins that communism had left behind were cooling; after the nineties, I was in exile in Greece, an economic immigrant. By chance, I met some of Maqua’s fellow villagers, who told me about a wretched man abandoned by everyone, who ended his life talking to himself. He cursed communism, the communists, and the notorious State Security every hour and moment. Then I changed my mind and felt deep pain for that doubly despised man; by the State Security as a breakable character, by us his fellow sufferers as a collaborator of the Security. But it was too late, nothing could be recovered.

At that time when I should have believed him, I did not believe him! But how could I, when all my fellow sufferers considered him a collaborator of the Sigurimi, I could not do otherwise! So honestly, I didn’t believe him! May God forgive me for my disbelief towards that conflicted soul! Anyway, I dedicated my pity to him, as a prayer in his grave, where the remains of poor Maqua had been buried in time. So in this environment, with these two people, I shared the work schedule, until we returned to the sleeping camp, where my friends were waiting for me. During work, I spoke little, or not at all. I did what I was assigned, with extraordinary effort, but I didn’t ask for help from anyone. When we returned to the camp, I felt exhausted; I often fell asleep without eating, from the excessive fatigue. I spent my free time and Sundays, when they didn’t send us to work, because they often forced us to work even on rest days, in the company of my friends.

When I was among them, I felt good; it seemed to me that I was living in a large family with a male composition, with grandfathers and great-grandfathers, with uncles and aunts, with brothers and cousins, that is, with people of the same kind. I felt like the pampered one of that cell, perhaps even overvalued sometimes. Meanwhile, I talked with them and told them about every event in the work environment, even about the most ordinary conversations that took place there. They listened to me attentively, analyzed what I told them, and came up with conclusions, and they even marked the line of my behavior. Generally, I understood my old friends, even when they reprimanded me. Everything they suggested, I took it for my own good, even when someone criticized me for hasty or impulsive actions. When they felt satisfied, I was proud of the appreciation they showed me.

I was still a minor, physically small and weak, so they gave me the nickname “Gavrosh.” They drew a parallel with the boy of the barricades from Victor Hugo. At that time, I didn’t know much about the life and activity of Gavrosh, except for a few short stories that I had read in school textbooks. Those years in schools, the positive heroes were summarized in the figures of Pavlik Morozov and Aleksandr Matrosov. Hugo’s ‘Les Misérables’ had not yet seen the light of Albanian publication. Russian was a mandatory language in the curriculum. They had transformed our country, so to speak, into an annex of Crimea. Russian everywhere; Russian movies, Russian books, paintings of Russian peasants with messy beards, who with their scythe-like sickles, were about to cut off your head; in choreography, Russian swans with their thin bodies, were ready to take to the air with their muscular wings, and take you to the distant steppes of Siberia.

So, Russian everywhere; other languages were considered either cursed, as expressive of the bourgeois-capitalist ideology, or a privilege of a minority of selected children, with the method of political selection. Thus, the gap between Russian and other Western languages deepened even more and reflected on our consciousness. Since the Russians had become stale to us, we hated Russian too! The extracurricular texts were only from Russian literature, but very weak and indoctrinated; the beautiful language of Pushkin, Lermontov, Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and a host of other great ones, was bastardized to disgust by the generation of Sholokhov and Fadeyev and their friends. You could hear everywhere: “Imya Lenina, slova slova…”! Memorie.al