By Ahmet Bushati

Part fifteen

Memorie.al/After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

Shkodra in the first years under communism

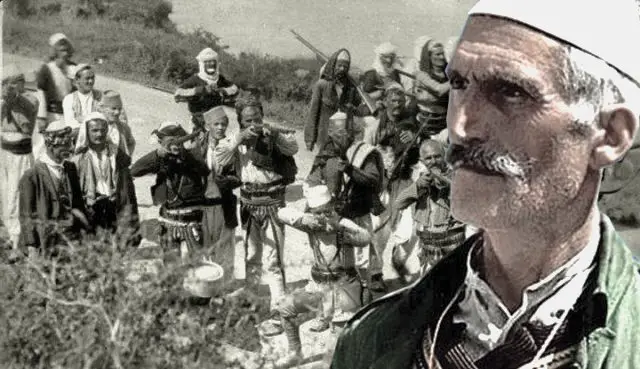

Postrriba, for its part, either did not show patience in this case, or was not aware of a larger plan. Perhaps the mistake of the Postrribas was that they necessarily linked the fate of the uprising to the fact that on September 9, their sons would go to the soldiers, thus missing the uprising. To finally decide on an uprising or not, the leadership of Postrriba set a meeting for September 8, about which a reliable courier informed the prides of village after village. So, on the appointed day, September 8, the meeting of the three bajraks of Postrriba was held at “Kodër Boks” and precisely at the place called “Shegat e Ibros”.

The meeting was chaired by Osman Haxhia, brother of Adem Haxhia from six years ago. Representatives of the three bajraks participated in it, such as; Abdulla Seiti, Selim Rraci, Smajl Duli, Muho Dyli, Emin Zyberi, as well as with the word taken from Myrto Dani, the flag bearer of Drishti, who was absent that day. The meeting decided that the next day, September 9, before dawn, all the fighters would gather in Fushe i Shtojit, to attack Shkodra.

It was not yet day when three hundred men had gathered at the place designated the day before. Most of them had weapons, and a small part was equipped with circumstantial means, which in any case expressed the great determination of Postrriba for war. As they broke the telephone connection with Shkodra, they set off towards it with the belief that Shkodra would respond to their rifles with rifles. Many family members of Fusha e Shtojit had come out in front of their houses and watched with curiosity and emotion those determined and proud warriors who quickly crossed their field, on which occasion there were also some of them who joined them.

Starting from the purpose and seriousness of the mission on the eve of the war, it makes us believe in a special spiritual state that those warriors must have experienced and, for an atmosphere that the closer they got to Shkodra, the more solemn and encouraging it must have been for them. However, we know that when they arrived on the outskirts of Shkodra and, precisely at the barracks at its entrance, the sun had not yet set on the ground, under the powerful signal “Fall, men!” they quickly passed the encirclements of barracks and houses around them and fired their rifles from many sides. The army, on its side, raised to its feet from the first shots, but surprised by the sudden attack, would for a while seek nothing else but to defend itself. Residents of the surrounding area would tell us from that day on how the Postrribas had crossed the walls with weapons in their hands and, shouting; “Hey, you Stalin’s puppies….”!

The Postrriba Uprising

While the rifle fire was roaring in the direction of the barracks, people everywhere in the neighborhoods of Shkodra had come out in front of their houses, asking their comrades loudly: “Do you know what these rifles are?” The fighting, which took place in close proximity between the opposing sides, was fierce for as long as it lasted, but since the Sigurimi army was increasing in numbers and armament from moment to moment, the moment came when the insurgents could no longer withstand their powerful counterattacks, and since Shkodra was not falling to them, as the insurgents had believed, their leaders were finally forced to issue the call for retreat. The plan of the insurgents, after breaking the government forces, to open the prison doors, take the prefecture and then, with a large army of volunteers coming out of the city and districts, to enable the uprising of the entire North, had failed to their greatest despair. Postrriba had mistakenly calculated that after its attack, Shkodra would join it. In fact, there had been no agreement on that matter, and by then times had changed more than the postrriba, some distance from Shkodra, could have understood.

Postrriba, with no more than three hundred brave men, had dared to attack with weapons and without weapons a strong and cruel power, just as three hundred Spartans once did great Persia, confirming once again its traditional patriotism and, once again, engraving in the historical memory another page of honor and glory for itself, Shkodra and the entire country. Even the forced withdrawal of the insurgents would reflect great organizational and moral values, as they supported it in their best dispositions. Thus, while a part of them, with resistance, placed in the center, would nail in place the powerful attack of the Sigurimi army, the others on the flanks, with the same determination and spirit of responsibility, would not allow the government forces to encircle the insurgents, on the contrary, they would enable the latter to cross the field and capture the mountain without risks.

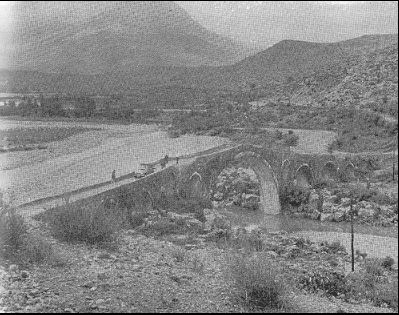

At the beginning of the retreat, the insurgents would allow Elez Bazin, from the village of Kullaj, to be killed, to be the first martyr of that uprising. Next, at the place called “Llomat e Rusit”, Jonuz Salja, from the village of Boks, would be killed, and further up, at Ura e Mesit, the third martyr, also from Boks, Osman Hyseni. Also from Boks would be Ymer Zeqiri, whom they had accidentally shot, and the partisans who had remembered to kill him, as if they had not noticed that they had found him, would have covered him with stones until he was alive. When the next day his family asked to free the “corpse” from the stones, they would be amazed to see that their man was alive, with only a few wounds on his body.

At the entrance to the village of Kullaj, the old and rare brave Sait Duli, having taken a favorable fighting position, would single-handedly block some of the government forces in place, thus giving the boys of Postrriba an additional opportunity to continue their climb up the mountain. After some time, Sait Duli would be blocked by his rifle and would finally be captured alive by the Sigurimi forces, who, after barbarically torturing him, would send him half-dead to Shkodra, where he would never arrive, because at the entrance he would begin to give up his life and, in order not to prolong it any longer, the partisans would shoot him on the spot.

Around noon that day and for several hours after lunch, the slopes of Mount Maranaj, through the occasional barrage of machine guns – which, as the fighting moved ever higher up the mountain, gradually weakened – would sadly convey to Shkodra the echo of the failure of the uprising. The rifles and machine guns had not yet all been used up, when many Shkodra citizens, with their eyes fixed on the mountain above Postrriba, would sadly notice thick plumes of black smoke, which, like merciless symbols of communist revenge, rose into the sky of Postrriba, which was burning for punishment.

Meanwhile, everywhere in the villages of Postriba, for fear of reprisals, many family members would rush out of their homes in great panic and with great haste and fear, take whatever they could to save and, with all their lives at stake, would take to the mountains with the aim of finding a friend, a forest or a cave. At dusk that evening, the Sigurimi would set up an operations headquarters for each village of Postriba, as well as an investigation center, at the head of which would be placed the notorious executioner of Shkodra, Zoi Themeli.

A beast of prey does not rush at its prey, as was unleashed on Postriba and Shkodra and its surroundings by the criminals of the communist regime of that time. The opportunity for them to vent their wildest spirits had come at their doorstep. Arrests began everywhere in Postrriba. At sunset, in terror, several men were shot in front of the people who had gathered there, and in front of their own families. Thus, in Dragoç, that afternoon, Hysë Velushi was shot, in Kullaj, the brothers Ymer and Ahmet Zeneli, while, to even greater sadness and horror, in Boks, Rrash, Kullaj, Dragoç and even as far as Vorfë, – where the treacherous partisans had had their safest nests until two years ago – several houses were set on fire, the acquaintances said.

Finally, after a long and truly hellish day, night would fall on Postrriba, a night like the night of the grave, with houses closed prematurely and without any sign of life inside, while above in the sky, thick columns of black smoke mixed with flames continued to show sadly far and wide what was happening to the now subdued Postrriba.

The next day, on September 10, the Security forces, according to lists drawn up during the night, or even earlier, would arrest many of those who had been involved in the uprising and shoot some of them, such as Reshit Begir, Halil Dauti, Rexhep Idrizi, Metush Ali and Ibrahim Selimi, all from the village of Kullaj. From Myseli, on that occasion, they would shoot Sylo Gjeta, as well as the brave Shkodra man, Qazim Rroji, who, for as many hours as he was connected to the above-mentioned post-terrorists and until he fell to the ground from the bullets, would never stop insulting the rulers and communists in general, calling them with all his might: “Low criminals”, “hora” and “vagabonds” without even sparing the names of Enver, Tito and their Stalin.

With the aim of terrorizing, the bodies of the executed would be left exposed for the people to see for two consecutive days, without allowing their families to pull them out. On the same day, another Shkodra man named Sadik Mlloja was also shot. The most horrifying scenes would follow one another. That land of Postrriba that was burning and those people of it, had not even heard of the kind of barbarisms that they were now trying on themselves. Among other things, the Sigurimi forces would gather the people in the centers of villages, bring the “guilty” men there and, as if to dehumanize them more than to torture them, tie them up as they were, beat them with sticks in the eyes of even their own family members, and in the end, separate one or two from the group, and shoot them right there.

On the dark evening of that September 9th, Zoi Temeli and Aranit Çela, – without a doubt the two greatest executioners of Shkodra for all time – after they had returned from the Field of Shtojit, stained with the blood of several men, with the intention of being seen by the “reactionary” people of Shkodra and, as if in defiance and boasting against them, they would devour them in the “Adriatic” cafe, right at a table next to the glass window that fell onto the sidewalk, not far from the piazza street, that evening without people.

There, high in Doma, the Pursuit Forces had captured and shot Idriz Ibro, Halil Meti and Avdi Zeqiri, all three from the village of Boks. Among the tortures, they had killed Muho Fetahu. The wise and patriot, Ymer Beqiri, after having tortured him to death – with Zoi Temeli himself participating – they had thrown him from the upper floor window of a peasant house and then shot him. This Ymer Beqiri had also been imprisoned and interned by the Italians, together with Adem Haxhi, as patriots they had been.

After many efforts, the Sigurimi had one day managed to also bury the cave where the brave martyr Murat Haxhia, the inspirer and main organizer of the uprising, was buried. Surrounded on all sides by numerous Security forces and after a fight lasting several hours, he had killed two soldiers and was finally left without ammunition to continue the resistance, he was captured alive, to be shot after some time. Hajdar Dani of the Drishti bajraktare house was also shot. It should be noted that on this occasion, large quantities of agricultural and livestock products were seized throughout Postrriba, as well as three thousand heads of cattle and sheep. When Postriba attacked Shkodra on September 9, from the Rus neighborhood, another group of fighters, mainly from the villages of Ragam and Sheldi, in order to show solidarity with their Postriba brothers, would travel the road with weapons in hand to Shkodra and stop at the place that was then called “Kallamat e Xhuxhës”, a suburban neighborhood of the city, on the edge of the Kiri River.

It is known at least that the Pashukej family of Sheldi, residing in Ragam, was one of the most active that day and that from that family, a few days after the uprising, Tish Pashuku would be shot in front of the people and after him Deda, while the other brother Ndreka, after a long investigation, would die in prison. There is also talk of an academic officer named Ndoc Ejllit who escaped, and on that day of the uprising, he had strongly supported the retreating forces with a machine gun he had. Many were those Postribas who were imprisoned on the occasion of their uprising, having first tested the Sigurimi with his tortures and, later, prisons and labor camps, to continue to show in all cases their character of resistance and loyalty. Or were they not also very religious! When in the Beden camp the day was a year of hardship at its peak, the Postribas like no other and to the surprise of everyone, would keep Ramadan, and not break it, not even after several times they had drawn blood from their mouths.

What would happen to Shkodra after the Postriba uprising?!

After the “Postrriba Movement”, Shkodra would be subjected to a terror and persecution that, of course, history, including the last two lifetimes under the communist regime, had never known. The “movement” of Postrriba would serve that regime as a pretext to trap all its opponents without exception, known or imagined. As according to communist logic – in contrast to the Nazi postulate; “one day of terror, one year of peace”, – Shkodra wanted to be subjected to a continuous terror, in order to make it pay not only for its oppositional stance of the last two years, but also for its past, to pay for its tradition, its genuine Albanian worldview, the brain and culture that it had; to also pay for its nobility, pride and collective consciousness, and consequently, its traditional solidarity. The instruction from the center was for Shkodra to kill them in all its vital elements, physical and moral. It wanted to fight them mercilessly in its entire being, including history and future. And it wanted to fight them in such a way and to such an extent that it could never rise again.

In connection with the above, the Ministry of Internal Affairs would send on that occasion to Shkodra as investigators, its loyal cadres, proven in crimes, such as; Nesti Kopali, Zoi Shkurti, Pilo Bregu, Sirri Çarçani, Abdyl Hakiu, Nesti Kopali, Ali Xhunga, etc., all of whom were from the south, who would keep criminals and criminals from Shkodra close to them and dependent on them, such as Fadil Kapisyzi, Dul Rrjolli, Xhemal Selimi, etc., up to the names of Asllan Lic, Dulaq Lekić, etc., etc., while the wiretapping was also very intense. We can say that the ghost of terror during those days wandered around every house or citizen even slightly known in Shkodra, remembering the prison, the torture and why not, even the premature death. Thus, with the standard accusation of “being connected” or “knowing” about the “Postrriba Movement”, the most prominent and patriotic people of Shkodra and its surroundings, most of the old and young intellectuals, as well as the clergy, would be arrested on that occasion. Citizens were arrested continuously, day and night, so much so that due to their large number, the communist government found it necessary to immediately build many prisons.

Thus, large state and religious buildings, as well as large private houses, were turned into prisons, making the necessary modifications in them. The Pedagogical School for Girls, “Donika Kastrioti”, the Assembly of the Frets, the School of the Stigmatines, the former large Recruitment building, as well as the houses called Ceka, Sumej, that of the Muzhans called “Burgu i Togës” – formerly the Dormitory of Our Mountains -, of the “Gestapo”, of the “Çurçi” etc., a total of thirteen, including the Great Prison with several hundred prisoners inside. There would be hundreds of those Shkodra families who, during those days and especially nights filled with fear, would try with all their heart to turn off the shocking creaking at the door of the house, and once again the appearance of the Sigurimi people, who, addressing their family members, or the person himself who would arrest them, would coldly pronounce the well-known and fatal phrase: “We need you”, or; “We need it for a little work”, or; “for an explanation”.

There were many homes that on that occasion saw off for the last time and with tears streaming down their faces their parent, son, husband or brother, never to have them in their warm bosom again, because some of them would die at the hands of the criminal investigators of the Sigurimi and, there would be those who would be killed in the dark nights with the alibi they repeated that; “They were killed while trying to escape from prison,” like others, who would be shot by staged court decisions in any environment, such as former rooms in houses, offices, or even halls of institutions turned into prisons, and there were also many who, due to age or acquired diseases, would die everywhere in various prisons and camps, but not before they were once free and in their own homes.

To give our reader an idea of what happened to Shkodra after the Postrriba uprising, I am trying to briefly list some of those families and their members, who on that occasion fell prey to the dictatorship, precisely because of the values they carried, and which until then had given their tone to the life of their Shkodra, to the culture that it was radiating everywhere. Without claiming a better selection on my part nor for an inclusion of all those families or individuals, who with their imprisonment and suffering should take their deserved place in this work of mine, I affirm once again that I only reflect my experience as a citizen and as a prisoner for a certain period of Shkodra, under communism. Memorie.al