Memorie.al / The Balkans, and Albania as an integral part of them, have a history full of zig-zags and intertwinings. Massive movements and displacements of their populations from one country to another are also a part of it; a piece of this history are the “Arvanites of Greece,” or otherwise the “Arbëreshë of Greece,” and on the other hand, the Greeks or minority members, as we otherwise know them in Albania. Regarding the former, we recognize (at least after the nineties) several prominent figures, such as the president of the Arvanites of Greece, the distinguished scholar Aristidh Kola, and his tragic fate.

However, a material in German by a well-known scholar of our regional affairs caught our attention. He has been proven and recommended as a good and impartial connoisseur of the problems of these territories (Dr. Konrad Clewing) regarding the Albanians and Albanian-speakers of Greece, as well as the Greeks of Albania. He attempts to provide, with objectivity and in a summarized manner, their history and condition on both sides of the border.

We will try to adhere to the main issues that the German professor has addressed, referring to the essence and the message he wanted to convey in this study. The material, to be more precise, is taken from the magazine “Pogrom-Threatened Peoples,” no. 2/2001, authored by Dr. Konrad Clewing, a specialist for Albanian affairs at the Institute of Southeast Europe in Munich.

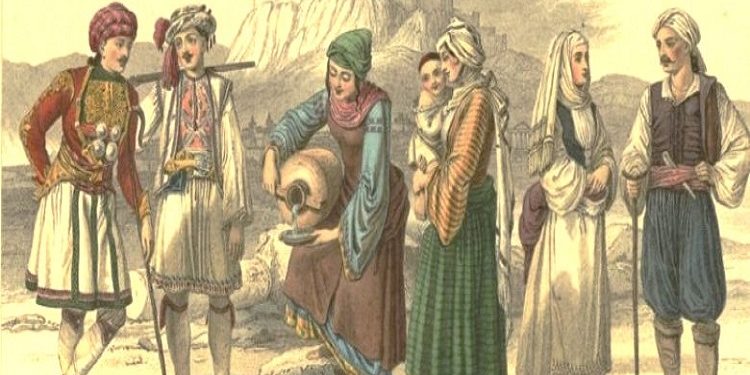

Let us see further what the German professor observes in his study. The segments of the Albanian-speaking population in Greece, divided by history, language, and national consciousness, do not constitute a unique grouping. For this reason, their designation in Greek as “Arvanites” is somewhat irritating to them. International science defines them as Arvanites, as the sole members of the community of descendants of migrants from the areas of Southern Albania.

The first and significant wave of their emigration occurred at the invitation of local princes and lords, starting from the 13th century, then in the 14th century, and continued until the 15th century. Since that time, the Arvanites settled in about 300 places and areas in the south of Greece; thus they were established in Boeotia, in the east, bordered by Attica (the surroundings of Athens), in some of the Aegean islands (among others in Euboea, Hydra), and in the Peloponnese.

The Assimilation Tendency of the “Arbëror”

In the beginning, they preferred to be identified with an ethnonym, a name common to all, and thus be called “Arbëror.” The language is also named after this word, “Arbërisht.” Over time, the majority also adapted to the Greek designation to define their linguistic origin, namely (Arvanitika-Arbërisht). The number of Arvanites, according to the criteria of linguistic use or self-determination based on consciousness, today reaches 150,000-200,000 people.

However, “Arvanitika” or “Arbërisht” is not only very strongly partitioned into dialects, but its speakers are now all bilingual, with a growing tendency to lose it permanently in subsequent generations. Linguistic assimilation was influenced by the fact that Arvanite culture has been entirely rural. Just like Greek society in general, they have long been orienting themselves toward urban areas, referring to – or rather, moving away from – the “Arvanito-Greek” model of life.

Urbanization, migration, and social movement have influenced the continuous loss of their language and dialect, and along with it, the change or loss of identity. Indeed, even Arvanites conscious of their origin now see themselves as half-Greek and half-Arvanite, meaning a politico-ethnic identity does not exist. The more nationalist Greek part propagates that one can be both Greek and Arvanite at the same time.

The lack of care for the Arvanite language and its culture, as well as the neglect for centuries and decades in all aspects by all state and religious institutions – namely the Greek Church (to which the Arvanites themselves belong) – shows that essentially the “agreement” will be accepted as long as the remaining Arvanite language is understood as a transitional phase toward full assimilation by the Greek-speaking world.

This, and the hostile environment toward Albanians in Greece after the 1990s, has led Arvanite clubs and groups to orient themselves more toward the idea of “Albanianism.” Arvanite clubs and groups were created toward the end of the 1970s.

The Reawakening of Albanian Ethnic Consciousness

A second, smaller group of Albanian-speakers consists of the inhabitants of several areas and villages in the border zone between Greece, Bulgaria, and Turkey – or, shall we say, Thrace. They are the last remnants of a large population displacement during the years 1922-’23, who concentrated mostly in this border triangle and whose speech resembles that of the groups of newcomers in the 16th century.

From the beginning of the 20th century, some representatives of the Albanian national movement also came here, while today in its Greek part, the Albanian language has nonetheless been preserved among the youth; in their consciousness, they feel both “Arvanite” and Greek.

A third grouping of Albanian-speakers today remains only partial: these are the Chams (Greek: tsamides) in a rugged area on the border with Albania, in the north of Greece, stretching to the shores of Epirus. Unlike the other two groupings, they are historically and linguistically part of a closed and compact Albanian-speaking zone; they had, meaning they have an Albanian national ethnic consciousness.

For example, among them, Albanian is called just as it is in Albania: Shqip. When the minority was created, its two parts – the Muslim half and the Orthodox half – were separated through the establishment of borders in 1913. The Muslim part was officially excluded from the exchange between Turkish and Greek populations, but in fact, this Muslim population was discriminated against.

As a result of alleged cooperation with Italian and German forces and the placement of Albanian officials in the occupied zones during the Second World War, the approximately 20,000 Muslim Albanians remaining in 1944 were mass expelled by Greek troops toward Albania. The remaining Christian Chams are not recognized as such by Greek legislation or the Constitution.

They are very little studied but seem to have an increasingly national consciousness and possess their language; they remain under great and continuous pressure from the Greek state. However, they do not manage to be officially declared. In general, the Greek state has not supported studies on Albanian-speaking groups and has not recognized them, although it has accepted their distinct cultural identity.

In some Muslim Cham areas, between 1936 and 1939, some “half-hearted” attempts were made to offer education in the mother tongue. To this day, Greece, due to its deficient policy toward minorities, has not contributed to overcoming problems and understanding in Southeast Europe.

The Other Side of the Coin: The Greek Minority in Albania

The Greek minority in Albania, and the Albanian one in northwestern Greece, is generally studied based on nationalist colorings. In fact, both groupings of these minorities are a consequence of the same phenomenon: in the wake of the Balkan wars of 1912-’13, new borders were set in areas that until then were under the dominion of the Ottoman Empire.

From this emerged a Greek minority group in the south of Albania, which today extends in a relatively compact zone (south of Gjirokastra), partially mixed with the Albanian population (in the neighboring coastal areas of the city of Saranda). Through internal migration over time, Greek minority members also came to the city of Gjirokastra, other cities, and the capital.

Here we must keep in mind that we are generally talking about members of the minority with an above-average level of education, which are very important for the representation of their interests. Even during the time of the communist regime in Albania, minority zones were clearly defined.

They included, excluding Himara, the entire region of the Greek-speaking minority. The protection of the minority at that time was nonetheless limited to the rudimentary preservation of the mother tongue and their education. Higher-level schools for teaching in the Greek language were established only after the 1990s.

The Greek “Game” with Figures

But how many Greeks are there in Albania? During the period between the two world wars, their largest number was counted, a number derived from the archives of the League of Nations. This figure varies from 35,000-40,000 Greeks.

The last population census in Albania during the time of monism, that of 1989, produced a number of 58,758 Greeks, while the Greek government nonetheless does not have an exact figure that it claims, but the number often claimed publicly in Greek society and media is 300,000-350,000 minority Greeks in Albania.

Both statistics are expressions of ethnopolitical thought. According to the election results of 1992, especially of the Human Rights Party, then Omonia, the number (even before the great wave of emigration and mass departure of Albanians for economic reasons toward Greece) is determined most reliably at 100,000-120,000 people.

The registration of the number of 300,000-350,000 also includes a large part of the Orthodox Albanians and the Aromanian community or minority. This almost expansive notion is also used by political representatives of the Greek minority in Albania, contributing fundamentally to the concern of Albanians regarding the artificial growth of the Greek minority there and the impact on relations with Greece.

The possible consequences of all this are ethno-national polarizations, as in the local elections in the communes of the Himara zone in the autumn of 2000. It is regrettable, meanwhile that the organizations of the Greek minority in Albania called for a boycott of the population census in April 2001. The debate over the final determination of the minority’s number is, even for its own members and representatives, one of the heaviest burdens and challenges.

THE POLITICIAN AND DIPLOMAT

Theodoros Pangallos: The Arvanite Language Must Not Vanish

After 17 years of studies, research, and travels through the territories of Epirus, Florina, Konitsa, Thrace, Corinth, Attica, and Boeotia, where the Arbëror (Arvanites) live and their songs are sung in Greece, the musician-writer and singer Thanasis Moraitis has brought an anthology of great scientific, historical, linguistic, and musical value. It contains over 140 musical materials written with texts transcribed in Greek and translated into Albanian.

In this presentation at the beginning of 2003, the Greek politician Theodoros Pangallos also spoke. Among other things, he said: “For those of us who were born in homes where our grandmother spoke ‘Arvanitika,’ this language – which is not as some ‘fools’ say, Greek with some other words – is Albanian, the pure Albanian of the 14th century. This is also confirmed by today’s Albanian immigrants who are in Missolonghi and tell us: ‘You speak the old Albanian.'”

“This is very logical from a linguistic point of view, as the language of the Albanians who settled here in the 14th century saw their language evolve into Greek, and what has come down to our days was the old idiom of Albanian.”

“For us, the loss of the Arvanite language is like having lost the homeland, because it contains a culture not under conditions of oppression, because no one could oppress the Arvanites in Greece: they led Greece, they were generals, prime ministers, presidents, and owners of the capital, but they themselves ‘swallowed’ their past because they were fanatically convinced they were Greeks.”

“With the help of teachers, they managed to eradicate the Arvanite language which no one speaks today, at least from my age and below. Now, thank God, we still have some grandfathers and grandmothers who speak it. However, it is a pity for this language to be lost, and I believe the work done by Thanasis Moraitis helps so that Arvanitia is not a lost homeland.”

“The language, culture, customs, and traditions must come to light, because otherwise, if they remain in darkness, it will truly be a lost homeland.” “Do not think you can eradicate the Arvanites. Greece without Arvanites and Arvanites without Greece cannot be,” Aristidh Kola used to say.

CULTURE

Disc with Arvanite Songs

15 years ago, thanks to the will and ambition of the Arvanite scholar Aristidh Kola, Dhimitri Leka, and the singer Thanasis Moraitis, it was made possible to produce the first two CDs with Arvanite songs titled “Arvanite Songs” and “Mountain Roses,” which contain a collection of several Arbëresh songs from Southern Italy and the Arvanites of Greece. These two CDs are the only ones produced in all-Albanian history in the Arbëresh/Arvanite language./ Memorie.al