By Marcel Hila

The first part

-Visits to places of suffering, death and disappearance…! –

Memorie.al/It was August 23, 2019. We left Tirana for Tepelena. We arrived after about three and a half hours. Because, I believe it is known by everyone, this day is the commemoration of the victims of totalitarianisms, worldwide: Nazism, Fascism and Communism. The Information Authority for State Security Files, where I work, had planned a memorial visit to the former Tepelena camp, a place of internment in the period 1949-1953.

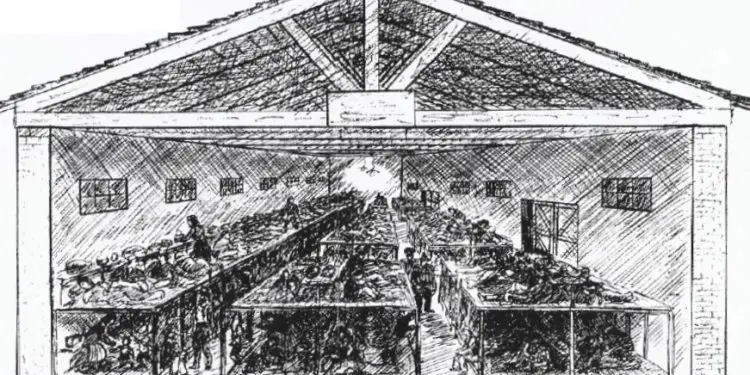

The bus bringing the work personnel arrived. Some had come in their cars. We entered the large courtyard, in the camp of the former camp, once a military ward, built by the Italians, during the Italian-Greek war 1940-1941 and remained so until their departure.

When communism came to us, it remained a guild, as it had been….!

Internment camps were set up in the early years, I’m talking about the end of 1944 and the beginning of 1945 and onward, such as in Kuç of Vlora, in Porto Palermo, in the fortress of Ali Pasha, in Vajgurore Bridge, in Berat, in Valias of Tirana, in Kruja. But many others were needed, for the great influx of internees, which increased every day. Then there was the break with Yugoslavia. We are in 1948, the months of July-August. Now the border was open and saw the possibility of protection from the Ministry of the Interior. This caused many to flee.

Mainly those who had gone to the mountains as members of “gangs” and who were now given the opportunity to leave the borders without clones and wires, poorly protected and scattered everywhere, and the Yugoslavs were accepting the newcomers and not turning them back, also to the anger of the Albanian communists, who betrayed, because, to preserve his power, Enver Hoxha joined the Soviets and instantly turned his back on Tito. The escape was a real hemorrhage. Up to half of the inhabitants of the villages escaped: in Kukës, Tropoja, Dibër, Theth and Vermosh. Then, the communist regime, powerless to stop this flow, decided to intern in the south, mainly the northerners who left.

So, in the created circumstances, he set his sights on finding places to gather the victims and made a place of internment for family members – that is, women, children and their elderly parents – the destroyed camp that had no conditions: that of Turan, in near Tepelena. But, as mass deaths began, mainly of children and the elderly, the camp was moved to Tepelena, where we were talking, near the city, where the Italian military ward had been. Human flows continued during the years 1949-1953. According to statistics, the inhabitants of that hell, for this period of four years, were about 5,000 poor Hallejins, including the victims who died and others who were raped.

The border with Yugoslavia was somehow already closed, but people fled to Greece, as much as they could, because the Greeks did not send them back. And there they brought terrible news: how small children were considered enemies of the people, how they died without food and medicine, how old people died; how mothers saw their children dying in their arms, powerless to help them, surrendered, suffered terribly and how some had gone mad when two children had died in one night and how someone had even attempted suicide.

It was the time when Albania tried to be admitted to the United Nations, but Greece, now that it knew about these secrets of its border country, decided to prevent the membership, until it put an end to the cruel treatment of the innocent, and in this case, mentioned the fresh data he had provided: “In Tepelena”, – he said, – “innocents are dying. This camp is an Albanian Auschwitz. Without closing this concentration camp, forget that we will vote for admission”.

And the regime, out of the need for international recognition, so that this stain of the scandal would no longer be mentioned and be considered as a blocking condition, in this year, 1953, decided to close it down.

Today the buildings – not buildings, but several barracks where the Italian soldiers once slept and then the deserted internees, somewhere around seven or eight in all, long, very long, almost eighty meters each, and some fifteen meters wide, are without roof, ruins, in the open sky.

In the middle of the yard, 300 cypress trees were planted, in memory of the three hundred children who died there, all without a grave. The great heat of this summer, which was completely without rain, had dried some of them, without growing well. No one cared to water them. A yellow color surrounded them, which was the grass burnt by the strong, scorching sun. While the anemic cypresses, weak and trying to flourish, were severely damaged by the lack of irrigation.

It can be seen that the memorial site for the victims is not taken care of. When we came, someone, remembered at the last moment, took a long water hose, put it somewhere at a tap, far away, and started watering the orchard. (As a reminder, the cemetery has cypress and cypress trees that were used as trees of death, because they do not flower in the spring, they do not flourish, they do not bear fruit to remind us of life, they do not put down roots to deform the cemetery and bring the bones out. That is how they were used which always as elements of a liturgy of death old human experience).

At the entrance, where the command used to be, where the guards and policemen used to sit, today there is a mass of ruins, fallen inside. Right at the entrance door, where the young women were taken out to cut wood on the mountain for the command, for the houses of officers and policemen, for the Party Committee, for the Executive Committee, for the Department of Internal Affairs, for the various institutions, a common pit was opened there, called collective, and the dead of the previous day were buried.

The desert entered there. If someone else died, the same practice was followed. And the pit grew bigger every day. Those women and mothers who went to work had to pass in front of the place where they had buried their children yesterday. What horror! There are no words that describe it. I must specify that since in Turan, the initial camp, as stated, the conditions were completely lacking, many children died every day. One night 33 died. The screams and cries of the mothers did not stop all day. And so, it was thought that the camp should be transferred to the ward, which we are talking about.

And since the people were terrified by the cemetery that was filled every day with their relatives, and that was right next to the entrance-exit door and that when the women and mothers went out for work every morning, they shot to open the hole to put them in there. the next dead person – a pit that grew every day – it happened that the shovel, while digging, came across the flesh of the one who was buried yesterday and pulling it out and also brought out parts of the dead people’s flesh, those deserts were filled with terror, because it shot that that waste meat was her child’s.

It was therefore thought to bury the bank of the Bênçe River, which passed close to the barbed wire surrounding the camp. So it was something better, because the family members took their dead, under the company of policemen, and where the camp authorities ordered them, near the water line, they buried him. The autumn and winter waters came and took the bones of the poor outside and took them with them.

In short, with three cemeteries in four years, but no graves. A large cemetery in Turan, which was emptied and the dead brought to the entrance door of the Tepelena camp, this pit was the second door; and at the end he is buried in the large collective pit at the corner of the Bênça River. Here was the third pit. Here the bones of the pit of the courtyard door were brought and rolled inside. Anonymous, collective, shared pit. Some internees assigned to burials did this work.

It must be said that the selection to bring them as far as possible had another purpose: the elders, that is, the fathers and mothers of the fugitives, their wives and children, younger sisters and brothers, had to be given another ordeal: none of the relatives who remained there could come to see them. The Northerners were all exiled to the South. Escape from the camp was out of the question, because there was barbed wire and armed guards.

A ration of cornbread with worms and a bowl of soup, which could not be called soup, was their food. Death every day. According to the testimonies, in addition to the 300 dead children, there are many old people who remained there. Therefore, this is a concentration camp, because the innocent were sentenced to isolation, without food, without medicine, without health care, without bread, without care. The real victims were the children.

You should know that even when the camp was ordered to be vacated and the remaining internees gained their freedom and went to their homes, they were not allowed to take with them the remains of their dead, buried and reburied relatives. . No one was allowed to open the big pit and check. They started them, just as they had brought them. Even today, many old men search for the remains of their mothers, brothers, sisters and grandparents. But they are not found.

Two years ago, while I was in the camp, – I had gone to visit, because I had my family members in this hell in the years 1949-1953, and I was walking towards the first barracks, because my mother told me that they had stayed there – a man in his fifties approached. As we started talking, among other things, he told me that: “A friend of mine, when he wanted to open the foundation for the construction of the new house he wanted to build, somewhere over there”, – he pointed to the river bank, – “came across the bones of the dead. Stopped the works!”.

– For holy fear?

– There are many possibilities!

– Out of respect for the dead?

– You can, definitely for that!

– Or that the family members of the poor should be notified to start the work and the procedures for digging up the soil and extracting the waste?

– Maybe! But he stopped the work.

People had come. Mainly, family members of those who had their parents here. Someone who was exiled himself, but who was young then, a child. There are also some women in modern clothing, which stand out immediately in today’s modern crowd. Also present are representatives of the local government, the Association of the Politically Persecuted, even a Bektashi cleric, a dervish, with his white and green robe, with many sides, with a typical dervish turban, who does not know how to I find its type and affiliation.

Then, the ceremonies began. First, pictures are taken of a memorial plaque, where it says that here, in this place, in the period in question, about 5,000 people were interned … and 300 children died. Photos are taken. Then, they spoke, remembered, mentioned the disappeared, those who have no graves. This is where the big wound comes out, here the suffering becomes pronounced. Someone sheds tears, someone starts to cry. When there, in that well-educated tangle of people, a woman appears who came from a village in Vlora, from Dukat … and after we start a conversation with her, she quickly becomes empty and starts telling us, who are from the Authority, but that we also have among our duties to interview people who have suffering to show, troubles to say.

– … My father was with the National Front. As soon as the communists came, they wanted to kill him. It was 1945. He was hiding. Then, he left, with great trouble in his heart. He had been married once and had three children from his first marriage. His first wife died. He married again. From the second marriage, with my mother, there were three more children Six. He had to leave, because death was certain. There was no escape. He fled to Greece; the father’s name was Veledin. He left with suffering in his soul

… When the communists were sure that the father had escaped, they exiled the mother, but they did not give her children with them, but the other woman’s. The mother ram died when she found out that she would not take her own with her. Only I was charged with him. They loaded the deserter with the dead woman’s three children and me into the car. Hers remained in the hut where we lived, in the village in Dukat. There they risked death by starvation. They were small, somewhere between three and five years old. There was no one to care. No one. They could die in an instant. Who would give them to eat? Dress up?!

– What happened to them?

– Someone took them from the village to save them from certain death, from starvation.

– I have done a great kindness.

– Mother was just crying.

– Did they bring you to Tepelena here?

– No, at first they took us to Berat, then to Kuçovo and then to Ura Vajgurore, they sent us to Kuç in Vlora and, when this camp was built, they brought us here in 1949. The mother never saw her children again. I had been very young when I was walking with my other wife’s children and my mother. Years passed like this, from ’45 to ’49 and ’50 and ’51 and ’52, I grew up and became seven or eight years old. I only remember that the mother was crying, crying, looking for her children and did not know how the boys ended up.

I wondered why my mother cried and never stopped. He went to work in the mountains, to cut wood for the Tepelena Internal Affairs Branch, for the Executive Committee, the Party Committee, ehhhuhha, winter and summer he toiled and crippled himself, he came dead from work. She found us, huddled together, waiting for her. We had nothing, nothing, no clothes, no medicine, and no food, nothing…!

– What did you live with?

– With a piece of bread and a bowl of juice… how do I know how we are alive…!

– What about your brothers from your mother, were they found?

– Yeah, we didn’t know anything and no one from the village knew that we had ended up in Tepelena and none of us knew who had taken the brothers, had they gone to the Orphanage, had they been taken by someone, or had they died. Had they been sent to the house of their maternal grandfather, who was not from our village, but from somewhere far away and not easily accessible? The mother just cried. I didn’t see him laugh once.

– What horror!

– How many provocations were made by those in command, how many threats and blackmails the young woman, but the mother never gave up…!

– Desolate woman!

– Pressures, provocations. He told me then, later, when I grew up, that then I was small and did not understand. My brothers, my mother’s children, as if the earth swallowed them, we never heard anything!

– What about father, did he come alive?

– Poor father, – and the old woman begins to cry – once, with extreme courage, he had managed to convince someone in Greece to take a submarine and, come to the shores of Dukat, go down and go to our hut. It didn’t find anyone. Terrified, he had gone to a friend of his, also a former ballist. He had been arrested and shot, but his wife told him that we had been taken and interned, while his children and those of his second wife had been taken by someone and it was not known where they were, because this family had also left the village.

In short, a colossal mess. The father, then, when he found out who had not yet been arrested by his former friends, went and met them one by one and took them with him. Everyone boarded the submarine and finally arrived in Greece and later in America, while we were suffering in Tepelena. The desolate father, with great sorrow in his heart, made his way to Greece. Then, he too fled to America. It wasn’t worth coming here anymore, because neither he nor his villagers knew where we all ended up.

– When the camp was closed, in 1953, did you return to the village?

– No, no, that’s out of the question!

– Where did they take you?

– In Savër of Lushnja, in exile, there. Since the father had been a ballistic missile, now on the run, they did not give us the right to return to our house, which they would probably have demolished,

– How long did you stay there, in Lushnja, in Savër?

– Until 1991.

– Until when?

– Whole life! There we got engaged, married, there our mother died, there we had children and only through democracy did we gain freedom.

– Amannnnn

– Yes … forty-six full years.

– What about mother’s children? Your brothers?

– They came one day by themselves, to Savër, to Lushnjë…!

– How did they come?

– They had searched and searched and in the end they went to ask the Department of Internal Affairs

– Right?

– Yes! They told him that we were in Savër … and the brothers asked them to come to us voluntarily, that is, to be exiled voluntarily.

– When this? In what year?

– In 1956, now they were somewhat older, but they were still young, teenagers,

– Where did they stay?

– A benefactor had gone to their house the same day that they deported us and took them. They were shaking with fear. He then took them to his own home, to his wife. He did not hesitate and accepted them. This man had died and then his wife too. The brothers did not want to stay with their children, older than these, and they searched for the mother and us in the department of internal affairs. They had reason to ask us. The mother went twelve years without seeing them, without knowing anything about them. He was withered with longing, completely dead. Memorie.al

The next issue follows