Memorie.al / From the eleven confessions of former political prisoners in this book, we learn a lot about severe physical and mental torture, harsh conditions in prison rooms, bad food, forced to do hard work, against a miserable payment, the rare visits of family members also due to the difficult economic situation, and the insistence that conversations with family members be conducted in the Serbian language. ‘Integra; has published a book, with the confessions of eleven Albanian political prisoners, who had been sentenced by the Yugoslav state, in the infamous prison of Goli – Otok, during the period 1945-1989.

In this book, titled “Distorted Shadows – book of memories, with the confessions of former political prisoners in Goli Otoku prison”, the eleven protagonists have this order: Hasan Kastrati, Jeton Radoniqi, Pajazit Jashari, Sabri Novosella, Teki Dervishi , Fadil Bajraktari, Basri Ibrahimi, Masar Shporta, Rrahim Rama, Ali Aliu and Ibrahim Kryeziu.

The narratives of these prisoners can be classified into four groups. The first group interviewed for this book can include; Hasan Kastrati, Masar Shporta and Ali Aliu, all three arrested, due to opposition to the Yugoslav communist regime during the 50s.

There are several moments since the end of the Second World War, which have had an impact on the formation of these detainees.

The first;it is immediately after the end of the War, when the opponents of the Yugoslav regime, mainly activists of the Albanian National-Democratic Movement (NDSH), were punished.

The second;it is in 1953, when Josip Broz Tito signed a “gentlemen’s” agreement with the Foreign Minister of Turkey, Mehmet Köprülü, to ensure the deportation of Albanians from Yugoslavia to Turkey.

The third;it is in the years 1955-56, when the Yugoslav government starts the campaign for the collection of weapons in Kosovo.

The fourth moment;is the process of Turkification of the Albanians, which is best illustrated by the case of the collaborator of the Yugoslav regime, Hashim Mustafa, who, while he was considered an Albanian, named his daughter Drita, but after he was registered as a Turk, due to the pressure of power, his son name Eroll.

This is best illustrated in this chilling excerpt from Sabri Novosella, one of the interviewees in this book:

“Father had a worker who helped him. You passed by the ‘Brick Factory’, I saw some people, who were gathered. I approached, when I approached there, it was our worker, whom the police had tortured in such a way terrible, during the “Action for the Collection of Arms” they said: “Either you gave us the weapon, or we left them alone…”!

He doesn’t have a gun. He did not want more torture and was hanged. I saw his dead body hanging…! It wasn’t even hung on a rope, because he never bought a rope before, but it was hung with a wire, which he found there, in the Brick Factory. That scene has remained unforgettable for me”.

All these also affected the second group of interviewees, where they can enter; Sabri Novosella and Teki Dervishi, arrested for activities against the Yugoslav communist regime, during the 60s, as members of the Revolutionary Movement for the Union of Albanians (LRBSH), which was founded by Adem Demaçi, Ramadan Shala and Mustafa Venhari.

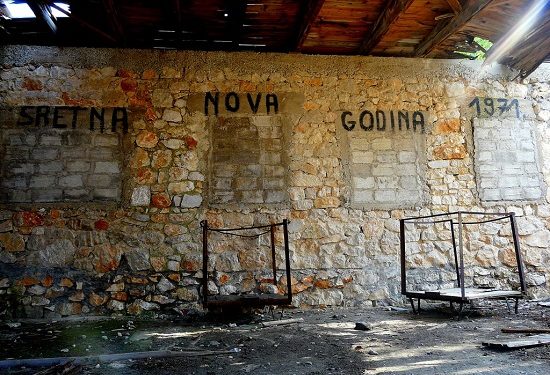

The prisoners of this group were arrested because, in 1964, together with other LRBSH activists, in the main cities of Kosovo, they had unfurled 99 Albanian flags and had written the slogan on the walls; RRNOFT ALBANIA – OUR NANA!

At the end of the 60s and the beginning of the 70s, the situation in Kosovo changed radically, both in politics and in the economy, in education, in culture, and so on.

At this time, at the peak of Kosovo’s development, at the end of the 70s, the activities of the third group of protagonists of this book took place: Fadil Bajraktari, Basri Ibrahimi and Rrahim Rama, involved in various illegal organizations of time.

Jeton Radoniqi, Pajazit Jashari and Ibrahim Kryeziu, arrested after the 1981 demonstrations, enter the fourth group of names from this book.

The members of these last two groups are not shaped by the repression of the Yugoslav regime, but more by the memories of the previous generations, about this repression, as well as by the nationalist propaganda of the time, both by the legal movement and by the illegal one.

While the first two groups were committed to the secession of Kosovo and other Albanian-inhabited areas in the former Yugoslavia and their union with Albania, the last two groups considered that the political circumstances in Kosovo and Yugoslavia, and also in world, had changed significantly and that commitment was required for the advancement of the status of Kosovo, from the Autonomous Region, to the Republic of Yugoslavia.

However, the commonality of all four groups is the commitment to the freedom of Kosovo. The other commonality is the suffering in prisons, although in the two decades after the Second World War, the first two groups suffered significantly heavier sentences than the last two, which they suffered in the last two decades.

From the eleven accounts of political prisoners in this book, we learn a lot about the severe physical and mental torture, the harsh conditions in the prison rooms, the bad food, the obligation to do hard work against a miserable payment, the rare visits of family members and due to the difficult economic situation, and the imposition that conversations with family members were held in the Serbian language.

Also, another thing that almost all of these prisoners have in common is their neglect after leaving prison: stigmatization, difficulties to find work, lack of resocialization, non-treatment of the traumas of these prisoners, which, unfortunately, do not it was done neither after the freedom nor after the independence of Kosovo.

These accounts are very important to understand our past, but for a more complete picture of this period, they are not enough. We also need the confessions of the political opponents of the activists included in this book.

We must also see how the activity of these interviewees was presented in the legal and illegal press of the time, as well as in important documents, such as the indictments of the justice bodies against the interviewees, the statements of the interviewees during the investigations, the defense words of them in the courts, as well as the final verdicts.

Finally, it is important to say that in the event of a reprint, it would be good for this book to be subjected to a basic proofreading, editing and processing, so that the texts can be read as narratives, and not remain only explanations of oral interviews.

Then, it would be good to clarify the criteria for the selection of the interviewees, to structure the interviews, to draw up short biographies, with relevant data for each of the interviewees, which would be preferable, accompanied by a photograph of the interviewees.

Also, the order of the interviews should be done according to the chronological criteria, at the beginning of the book, give the table of contents and at the end, the index of names, then some data about the prison of Goli Otoku itself, and so on. Memorie.al