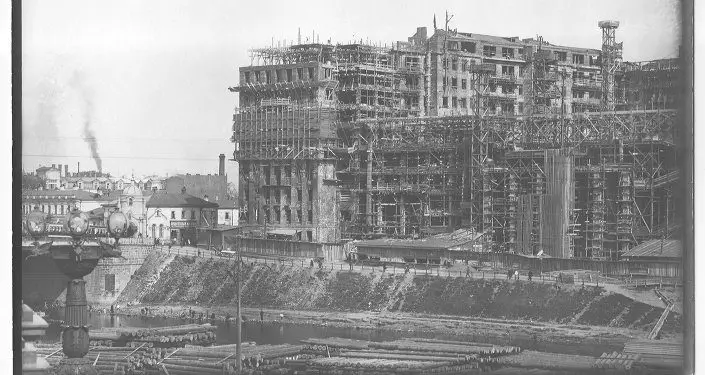

Memorie.al is exclusively publishing the reportage of American journalist Joshua Yaffa, who is a correspondent for the American daily The New Yorker in Moscow. In this report, two years ago, Yaffa described in detail the inhabitants’ descriptions of one of the largest and most important buildings in terms of history in this country. What is common in Russian jargon is referred to as the “Embankment House”. Through this description, comes the personal opinions of the few remaining residents of this building who tell their stories both happy and painful. The story of this magnificent, simultaneously gloomy building was recounted in the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the works of Yuri Trifonov and Yuri Slezkin. Cleverly described in the novels “The House on the Embankment” in 1999 and “The House of Government” in 2017, they show how the Soviet Communist regime managed, for at least a quarter of a century, to destroy dreams and lives during the Stalinist era. of his own idealists who had the “fortune” to live together in this building.

Continues from the past number

He quotes the journal entry of Yulia Piatnitskaya, whose husband, a Comintern official, was arrested along with their seventeen-year-old son at the “Government House” in 1937. Piatnitskaya was anxious for her son, and she flipped between two contrasting images of her husband. The first, an honest revolutionary, and the second, a savage enemy of the people. When she thinks of the former, she writes, “I’m sorry for her and I want to die or fight for her.” But when she thinks of the latter, I say to myself “I feel tired and disgusted, and I want to live in so I can see all those who were caught and I have no regrets for them. ” According to Slezkin, 800 residents of the “Government House” were arrested or interned during the sweep, calculated at 35 percent of the building’s population, 345 executed. After some time, arrests spread from residents to nannies, guards, stewards, and stair cleaners. The commander of the house was arrested as an enemy of the people and also the head of the well-kept department of the “Government House”. So many “enemies of the people” were being discovered that individual apartments were turning dark at an absurd speed.

In April 1938, the director of the Kuznetsk steel plant, Konstantin Butenko, moved to Apartment 141, which was vacant after the arrest of its former resident, a deputy commissar from the Ministry of Health. Butenko occupied all four rooms for six weeks before he was arrested, and his family was later interned. Matvei Berman, one of the founders of the Gulag, settled in the same room. He, too, was arrested six months later and shot the following year.

One afternoon not too long ago, I visited a woman named Ana Borisova, whose apartment is just outside my yard. Borisova is an amateur artist and poet. Her photos cover the living room walls, along with portraits of her faded family. Space has the feel of an airy lounge. She told me about her grandfather Sergey Malyshev, who was a Soviet official in charge of food supplies and trade. Borisova explained that he spent 1937 in a state of anxiety. “He had a foreboding,” she said. “He was waiting for them, always, and he almost never slept through the night.” One evening, Malyshev heard footsteps coming down the hallway and fell dead of a heart attack. In a way, his death saved the family. There were no arrests, and so there was no reason to bring his relatives out of the apartment. Since he died on his own, he has stayed with our family along with the apartment, and everything else, ”Borisova said. “And after that, nobody touched us.” My friend Tolya, the documentary director, told me how his grandfather, Iosif Fradkin, survived those years. Before the revolution, he gave himself the pseudonym of Boris Volin. The nickname Volin meant the Russian word volya, which meant both will and freedom. The nicknames were a popular Bolshevist fad. Vladimir Ulyanov called himself, Lenin, Iosif Dzhugashvili was called, Stalin, and so on. Volin was a tough, combative man. He took up a post at Glavlit, the Soviet Union’s Censorship Organization, and announced a decisive turn towards extreme class vigilance. One day in the fall of 1937, after arguing with his boss, a narrow-minded man named Andrei Bubnov, Volin suffered a heart attack. He spent the next few months in and out of state hospitals and treatment homes. Upon his recovery, he discovered that Bubnov, along with staff and another deputy of the ministry, had been arrested and executed. I warned Tolya that it must have been terrifying to learn that many of your colleagues and friends were liquidated in your absence.

We were sitting in his apartment, surrounded by stacks of antique family books and artifacts. The center of the apartment was his grandfather’s old studio, a charming room with a large deck and a wall of wooden and glass shelves extending from floor to ceiling. “The point is,” Tolya said, “that there were many others before this horrific discovery.” “One of Volin’s brothers was an employee of the intelligence service working in the United States under the guise of a military attaché. When he returned, he was arrested and shot. One of Volin’s sisters had married an NKVD officer, and they lived in the “Government House” in a nearby apartment. When the man’s colleagues came to arrest him, he jumped out of the window of his apartment and found himself dead. ” Volin was carrying a suitcase full of warm bedding ready for him in case of arrest and internment in Gulag. His wife burned an archive of letters dating back to his time as a Bolshevik emissary in Paris for fear that if he were arrested, he would be labeled a French agent. They told their daughter, Tolya’s mother, a set of specific instructions. Every day after school, she had to climb the elevator to the 9th floor, not the 8th, where the family lived. The action had to be for her to look down the stairs. If she were to see a secret police agent, then she had to go downstairs and run to hide, toward a friend’s house.

We talked about the heavy atmosphere, in that building, about that atmosphere that Tolya’s grandparents must have thought of, as the bright and just world they believed they had built began to cannibalize themselves. “They could only think of one thing, how to survive. I am deeply sure of this, ”he said. “They were not able to intervene to control the smallest things. The forces they had against were biblical, like fighting nature itself. “As the black storm rages on, the arrests are over. The last people to be ironically killed were the NKVD officers. “After waking up after the bloodbath, Stalin and the surviving members of the inner circle had to get rid of those who had administered it,” Slezkin writes.

It wasn’t long before a new tragedy struck the occupants of the building and the country itself, occupied by Nazi Germany, in June 1941. The “Government House” was evacuated, its inhabitants scattered in cities throughout the Soviet Union. Slezkin reports that about 5 percent of the building’s occupants went to war. 113 of them were killed. In Soviet consciousness, the war was an event as powerful a revolution. The conflict, Slezkin writes, “justified all previous sacrifices, voluntary and involuntary. He offered the children of the original revolutionaries the opportunity to testify, through more sacrifice, that their childhood had been happy, that their fathers had been clean, that their place was their family, and that their lives were really beautiful even in death. ” After the war, residents of the “Government House” returned, but the building’s early spirit was gone. During the 1940s, as new residents mingled with the old, and furniture moved inward, the place was, according to Slezkin, “noisier, more eccentric, and less exclusive”.

New blocks of elite apartments were erected around the city, including Stalin’s so-called quads. For this reason, the “Government House” ceased to be Moscow’s only prestigious building. The cult of Stalin and, in addition, the myth of Soviet virtue and extraordinary, that is, the bond that had held together the scattered survivors of the “Government House”, Slezkin writes, began to be dismantled in 1956, when Khrushchev, once a resident of the building, now the First Secretary of the Soviet Union, delivered a secret speech on Stalin’s crimes at the XX Party Congress. This retribution of the USSR infallibility was infuriating to the generation of true Bolshevik revolutionaries. Tolya’s grandfather, then a lecturer at the Institute of Marxism-Leninism, was devastated by the speech. His wife had died not too long ago, and Tolya told me that those two events “sent him to the grave.” He died within a year, at the age of 72. Tolya’s parents were typical members of the next generation of Soviet intelligence. No successful discussion outside the communist system, but privately ambivalent and disappointed. Tolya, like many of his friends, grew up in the protective shadow of Soviet Union power. One of his earliest memories was of Yuri Gagarin’s first space flight in 1961. His family watched on television, a rare device in Moscow in those days. “Gagarin made his flight and now we, the Soviet Union, were at the top of the world,” Tolya said, describing his mood at the time. “I felt at the center of the universe.” In those years, residents of the “Government House” were still de-facto members of the elite in the apartment I now rent, Sergushev’s son, Vladimir, living with his mother and wife, Nora. Sergushev’s name helped Vladimir get a job at the KGB.

He was an intelligent and wise man, but with weak nerves. In the 1950s, he lost an affair, full of secret documents, while on duty in Germany. For this, he quietly left the secret service. Vladimir was hired as a professor of agrarian economics and studied fruits and vegetables. He had a son, and then, in 1975, a daughter, my very own Navy confessor. She told me that when she was a child, the story of the building was largely forgotten, or intentionally ignored. Perhaps the most defining event in the building’s postwar life came in 1976, when Yuri Trifonov, a former resident, published his novel “House on the Embankment Road”, a fictional tale of his boyhood there.

Trifonov, who was 6 when his family moved to the palace, describes the building as a “large gray block with thousands of windows giving the impression of an entire city.” His father had a job high on the People’s Commissariat Council, while his mother was an economist at the Commissariat of Agriculture. Trifonov’s father was arrested as an enemy of the people in June 1937, when Trifonov was 11 years old. The following April, NKVD agents came for his mother. They took her out and forced her to wear only a pair of cash shoes, and a gray jacket, clothes that she would wear throughout the first winter in Gulag in the frozen steppes of Kazakhstan. Our mother paused for a moment and looked up to meet her children. She did not offer the usual words of condolence for her innocence or her subsequent return, but instead gave them a piece of advice that Trifonov reminded her of for the rest of her life: “Children, no matter what happens, don’t you lose your sense of humor. ” What Trifonov did not know until then was that his father had died and would no longer see his mother for 8 years.

Trifonov wrote “House on the Embankment” when he was 52, and the book’s characters are children of his generation, but he alludes to the trauma of purges only through supporting characters who suddenly disappear. This is also noted in the narrator’s transient note that “people who leave home cease to exist.” The book was an instant sensation among Soviet readers, and for this reason gave the building a new life, since then it was known as ” House on Embankment ”. Trifonov died in 1981, but his widow, Olga, 78 old, is a proud chronicler of her husband’s life and work.

We talked this summer at the little museum dedicated to the House on the Embankment, where Olga is the director. The museum, located in an apartment in the backyard of the building, is full of original objects, like the usual wooden furniture that Iofan, the architect of the building, designed for the residents. Trifonov and his sisters were evicted from the building after his mother was arrested, and he never returned. As Olga pointed out, he rarely talked about his years there. “Yuri was not a man who wanted to talk about the past,” she said. “He saved it through his literature.” In the early 80s, Olga said, the couple lived in a dilapidated apartment below a grocery store. Trifonov’s popularity was tremendous. His name was shortlisted for a Nobel Prize nomination.

One day, a senior Soviet official approached Olga and proposed that the couple be transferred to a four-bedroom apartment in the House of Embankment. It seemed a fantastic hit of good luck. “I went back upstairs with this silly smile, and right in the hallway, I said,” we are being offered to move to the Embankment House! “Trifonov smiled at me and said ‘Do you really think I want to go back there?’ Needless to say, but they turned down the offer. “For him,” Olga said, “this building contained his most joyful childhood memories, at the same time the most bitter and tragic, all mixed up.”

Tolya told me that as he grew older he became curious not only about the history of his grandfather, whose medals on Lenin’s orders appeared on the shelves of family books but also on many periods of Soviet history that were never discussed again… When he was about ten years old, he read “A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich” by Alexander Solzhenitsyn, a story of existence in Stalin’s camps. Later, he began to go through Solzhenitsyn’s “Gulag Archipelago”, a three-volume masterpiece that appeared only in cooperatives. In his university years, he, like many of his peers, was an anti-Communist, not completely dissident, but thoroughly disillusioned with official ideology. He developed a shared awareness of home. “Of course, on a rational level, I know the history of this building, who lived here, and all about the oppression,” he said. “But there is also a more personal experience. I was born here, I grew up here and I have spent much of my conscious life here.

In 1991, the collapse of the Soviet Union was treated with excitement and relief by many who lived in the “Embankment House”. Its inhabitants were no longer true believers in communism, and until then, it seemed hard to have a true believer left in the empire. The 90s in the building, as in all of Russia, were times of anarchic, exhilarating, and terrifying opportunity in equal measure. Pensioners moved out, their apartments seized by Russia’s new oligarchy. Mafia, from all over the former Soviet space, bought apartments at the most central address of the city, which still held a voice of privilege and power. Underground casinos appeared in some apartments, and others turned into hotels for migrant workers. My apartment was rented by an American oil company, then by an investment banker, followed by a professor from France, and finally, before me, a young politician conducting dizzying holidays disturbing neighbors. The most visible symbol of the era was a Mercedes-mounted roof logo on the building. The logo was placed there in a dark arrangement that was not discussed, let alone approved, by the building’s occupants. “The building was dreamed of as a small piece of paradise for the elect,” another colleague I knew in Moscow told Gleb Pavlovsky. “But this house lies on the sad ground and its inhabitants are doomed to carry a very difficult sadness.” No doubt, he added, the building is “cursed.” “As Pavlovsky told me, the Bolshevik revolutionaries who first inhabited the House on the Embankment,” though they were smarter than they could defeat the system created. But they lost control, they became puppets of something far greater and more powerful than any individual. And by the time that system began to devour people, it was too late. He sold his apartment in 2015 and is now renting a place on the outskirts of town. All in all, he said, I feel relieved to leave. “But I miss the ideas”.

![“After the ’90s, when I was Chief of Personnel at the Berat Police Station, my colleague I.S. told me how they had once eavesdropped on me at the Malinati spring, where I had said about Enver [Hoxha]…”/ The testimony of the former political prisoner.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)