Memorie.al is exclusively publishing the reportage of American journalist Joshua Yaffa, who is a correspondent for the American daily The New Yorker in Moscow. In this report, two years ago, Yaffa described in detail the inhabitants’ descriptions of one of the largest and most important buildings in terms of history in this country. What is common in Russian jargon is referred to as the “Embankment House”. Through this description, comes the personal opinions of the few remaining residents of this building who tell their stories both happy and painful. The story of this magnificent, simultaneously gloomy building was recounted in the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the works of Yuri Trifonov and Yuri Slezkin. Cleverly described in the novels “The House on the Embankment” in 1999 and “The House of Government” in 2017, they show how the Soviet Communist regime managed, for at least a quarter of a century, to destroy dreams and lives during the Stalinist era. of his own idealists who had the “fortune” to live together in this building.

House of Shadows

A few years ago, after looking at half a dozen apartments throughout Moscow, I chose a spacious building across the river in front of the Kremlin, otherwise known as the “Embankment House.” In 1931, when residents began moving inside, it was the largest residential complex in Europe. A self-organized world, the size of several city blocks. The Government House, as it was originally called, was a combination of the geometry of constructivism and the neoclassical pomp. It contained 505 cozy apartments that housed Soviet Union government commissioners, Red Army generals and Marxist intellectuals. On the day I visited, the apartment’s owner, Marina, a smiling woman in her forties who worked for a multinational oil and gas company, met me in the yard. She took me to the apartment, which had been her family for four generations. There were two bedrooms with a small balcony.

Successive renovations left the site without much detail of architectural authenticity, but as a result it was a comfortable home. Less apparatus in it, and more Ikea products. Tall windows in the living room overlooked the Kremlin’s wide curves. I decided to go inside. Until that time, the “House on the Embankment” was known to the citizens. It was also famous for its proximity to restaurants and bars. This was a refurbished industrial space that once belonged to the Red October confectionery.

A design and architecture institute had just opened along the way. I would often pick up my laptop and work in her café, which was decorated with vintage furniture. Soon, I made new friends in this creature. One of them was Olaf, a Dutch journalist and his wife, Anya, who worked at the design school. Also Masha, the owner of a popular French-style cafe in Gorky Park. In time, I also met Anatoly Golubovsky, a historian and documentary producer, Tolya’s friend. He’s 60, and he’s one of the most interesting storytellers I could ever know. Golubovksy, and his wife live in an apartment not far from my apartment, originally occupied by his grandfather, who was the chief literary censor in the Stalin era. The most striking thing about the building was and is its history. In the 30-40s, during Stalin’s purges, the “Government House” had a bad reputation for the highest per capita number of arrests and executions from any apartment building in Moscow.

No other address in the city offered such a convincing fact in the world of Soviet-era bureaucratic privilege, and the horror of the murders to which this fate was often directed. Popular curiosity about the building today views it as a kind of haunted, haunted museum of Russia of the last century. I asked Tolya what he did from the bad fame of our building. “Why does this house have such a heavy and difficult atmosphere?” he said. “That is why, on the one hand, its inhabitants lived as a new class of nobility, and on the other they knew that at any second they could be dragged down their stairs.”

A century ago, in the tumultuous autumn of 1917, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, seized a moment of political chaos in Russia. The empire had grown weak and fruitless. The previous February, Tsar Nicholas II had left his throne, bringing the closure of the Romanov era, a royal dynasty that ruled for over three hundred years. That October, Lenin and the Bolsheviks overthrew the interim government, seizing power and propelling the proletariat’s dictatorship. At the time, the Bolsheviks were not the country’s largest or most popular party, but they were the best security of their promises. They were, in essence, the first faith-based apocalyptic sect to take charge of a country.

This is the starting point of a new magic book by Yuri Slezkin, a Russian historian of Jewish descent who emigrated to the United States in 1983. He has been a professor at the University of Berkeley, California, for many years. His book, The House of Government, is an epic 1,200-page description that tells the story of the famous building and its inhabitants. In Slezkin’s account, the Bolsheviks were essentially a millennial cult, a small tribe that radically opposed the corrupt world. At the urging of Lenin, they attempted to bring about the promised revolution or facade, which would create a more noble and honorable era. Of course, that didn’t happen. Slezkin’s book is a tale of “failed prophecy,” and my own home in recent years is “a place where revolutionaries returned home and the revolution died”.

In the years following the October Socialist Revolution, as it would be called in Soviet literature, Bolshevik leaders found themselves modified as Communist Party officials. They faced the conflict of how to transform their sect into a church, that is, how to overcome the rhetoric of the last days and create a sustainable system of government. Lenin died in 1924, and Stalin, after maneuvering into power, declared that the global revolution was unnecessary, and that socialist utopia could be established in a single place. The “construction” of socialism was the acting metaphor for what became known as the Stalin Revolution. Which was defined by rapid urbanization and industrialization. Building frenzy was intended as a kind of creativity myth. On the first day, the Communist Party built the Magnitogorsk Steel Plant; in the second, the Tractor Factory in Kharkiv. In Moscow, citizens were fascinated by the subway, which began operating in the mid-1930s. Its gigantic stations, with their chandeliers and marbles, felt like mansions for the new Communist era. Inevitably, the builders of this new state needed a home of their own. After the revolution, senior Party officials had taken over rooms in the city’s safest areas, invading the Kremlin, the Metropolitan National Hotel.

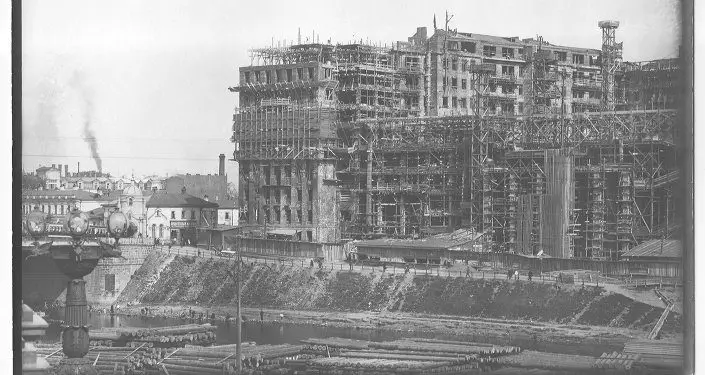

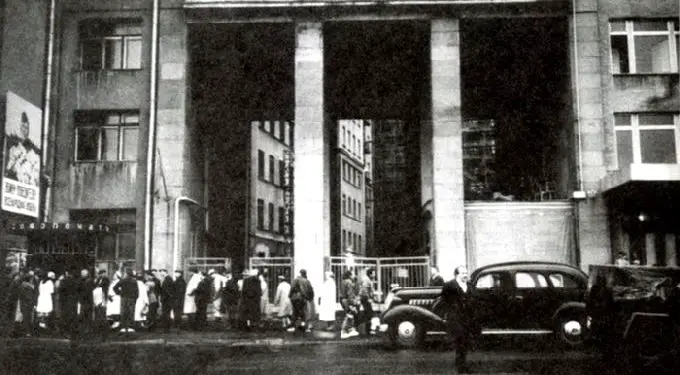

Such housing was thought to be a temporary necessity that would soon give way to a collective life. The first post-revolutionary years were a time of utopian experimentation in architecture as well as social engineering. Constructivist Konstantin Melnikov designed sketches for “giant sleeping laboratories” in which hundreds of workers could quietly go to work and then return to their nearby living areas. Senior Party officials were accustomed to the conveniences of their hotels and former nobility palaces. Construction of the “Government House” began in 1928, with a model, by Boris Iofan, of the “transitional type” that is, a utility building but which, for the time being, allowed residents to live in traditional family apartments. When it opened, in the spring of 1931, Slezkin writes, it had a bar-restaurant capable of serving all the occupants of the building, a theater for 1500 spectators, a library, several dozen rooms for various activities, since pool games, all the way to the symphony orchestra. And then he went on to the theater, some tennis, football, and basketball fields, two gyms, and giant shower rooms. There was also a bank, laundry, post office, child and senior care center, medical clinic, hairdressing salon, grocery store, market, and movie theater for 2000 spectators. To finish with the café, library, and amusement halls. The flats were distributed among those responsible for the new communist project.

Nikolai Podvoisky, a former seminarian who led the attack on the Tsar’s Winter Palace in 1917, moved to Apartment 280. Boris Zbarsky, a chemist who headed the ballooning work of Lenin’s body inside his mausoleum, in the Square Red, was given Apartment 28. Nikita Khrushchev, then forty-year chairman of the Moscow Party Committee, moved to apartment No. 206. Iofan himself took a giant loft. My current residence, on a less favorable side of the building, was occupied by the family of Mikhail Sergushev, who was born in a peasant family in 1886 and became interested in socialist politics while working at a china factory in Riga. My landlord, Marina, Sergushev’s great-grandmother, told me that, in the years after the revolution, he traveled to hundreds of regions, helping to create communism in all Soviet rural areas. Only his word could decide the fate of local officials, even entire villages, and agricultural cooperatives. At first, Sergushev moved to a seven-room apartment in a mansion where his son would bike from room to room. However, Sergushev’s health was poor, and in 1930, he died of tuberculosis. The following year, his wife and son were transferred to the Government House.

The transition the building was meant to make was never made. Instead, its inhabitants were further displaced by collectivist ideals and adopted lifestyles that looked no doubt aristocratic. Residents had prepared their own clothing and food so they could spend the whole day and much of the night at work. Whereas, their children could be quiet, reading Shakespear and Goethe. The building had a large staff, with one employee for every four residents. Slezkin, likens the “Government House” to a capital city in New York City, along Central Park, where residents could dine in a luxurious restaurant, and play tennis and cricket on special grounds.

A report prepared for the Central Committee of the Soviet Union in 1935 showed that the cost of running a “Government House” exceeded Moscow’s rate by 650 percent. To the extent that the “House of Government” facilitated social transformation, from an ascetic sect to a clerical elite. Just as the building fell short of its promise, the early Soviet Union failed to implement its prophecies of a just, classless society. Food shortages, unresolved housing, and many disgusting aspects of life continued. All the millennial movements face this moment sooner or later. This is the “Great Disappointment,” a term that Slezkin borrowed from the story of William Miller, a farmer in Massachusetts, who prophesied that the apocalypse would occur in 1843, and when it did not, moved the date to October 22 1844.

The Soviet Union had experienced two revolutions, that of Lenin and Stalin, and yet, in Slezkin’s verses, “The world is not over, the blue bird does not return, love does not in itself reveal all its profound tenderness and charity, death, mourning, crying and the pain does not disappear. ” “What to do then”? The answer was human sacrifice, “one of the oldest locomotives in history,” Slezkin writes. “The stronger the reception, the more unbearable the enemies, the more unbearable the enemies, the greater the need for internal cohesion, the greater the need for internal cohesion, the more pressing the search for human sacrifices. ” Soon, in the Soviet Union of Stalin, purges began. There would be no such accidents or mistakes. Any deviation from the virtue and from the promised achievements was the result of deliberate sabotage. This is the logic of black magic, witch spirits and witch hunting. It was only natural for the victims of the hunt to be among those who set in motion the original prophecy.

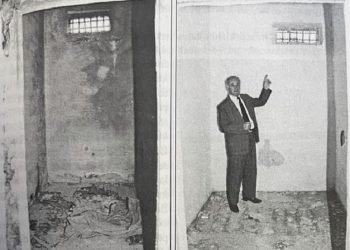

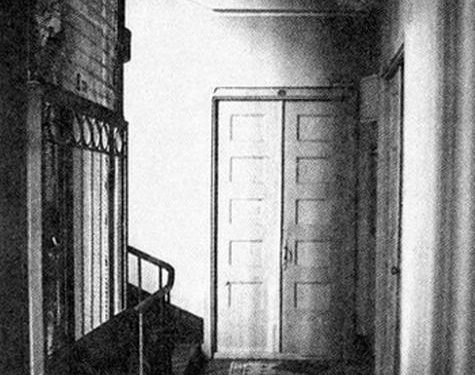

It’s hard to imagine right now, a building, with a children’s playground in one of its courtyards and a cozy Asian bar on the ground floor. But throughout 1937 and 1938, the “Government House” was an arena of disappearances, arrests and deaths. The list of arrests was prepared by the NKVD, the Soviet secret police, which later became the KGB, and approved by Stalin and his close associates. The arrests occurred in the middle of the night. A group of NKVD officers arrived at the building with the “Black Ravens” nicknamed the standard secret police vehicle, which created the silhouette of a predator landing on its prey. One story I have heard many times, but that seems unbelievable, is that NKVD agents sometimes use large sewage pipes to enter apartments, inside a suspect’s home without having to knock on door. After a trial, which could take three to five minutes, the prisoners were taken to the left or right. On the left is imprisonment, while on the right execution. Most residents of the “Government House” were taken to the right, writes Slezkin. No one publicly mentioned the accused or spoke about the plight of surviving family members. All in all, Slezkin points out, those who lived in the “Government House” believed that the enemies were actually everywhere. Memorie.al

Coming tomorrow

![“After the ’90s, when I was Chief of Personnel at the Berat Police Station, my colleague I.S. told me how they had once eavesdropped on me at the Malinati spring, where I had said about Enver [Hoxha]…”/ The testimony of the former political prisoner.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/admin-ajax-4-350x250.jpg)