From James Cameron

Part Two

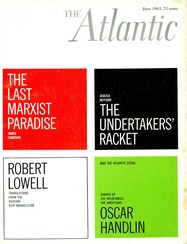

Albania, the Last Marxist ‘Paradise’

Published in “The Atlantic” magazine, 1963

Memorie.al / Born in Scotland, educated in France and England, James Cameron had been a reporter for more than twenty-five years. As chief foreign correspondent for the London News Chronicle, he was one of the first Western observers to travel freely in Mao Tse-tung’s Red China, and his account of what was happening inside that communist country was laid out in his book Red Mandarin, published in 1955. He now tells us how he managed to penetrate Albania.

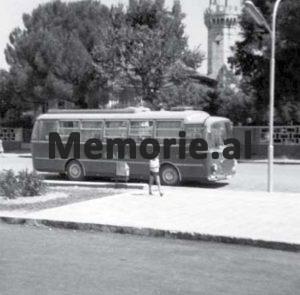

Tourist in 1960s Tirana

It was hardly expected that the streets of Tirana would now echo with the shouts of boys in expensive clothing and Mandarin-speaking cadres in blue canvas suits. Yet I had just heard that two new airplanes with Chinese specialists had recently flown into the country to perform aerial pesticide spraying over the planted fields and olive groves. Could the Chinese advise the Albanians on olive harvesting, where that tree had grown there in that Mediterranean climate for more than two thousand years?!

The fact was that the few hundred Chinese in Albania were behaving as the Russians behaved in China eight years earlier: keeping their heads down, away from curious eyes. Only once, on my second day in Tirana, did I accidentally wander into the wrong section of the restaurant, and there they were, a couple of dozen Chinese, eating in a partition designated for them. They looked up in a very startled way, and I retreated in embarrassment.

For two days, then, before I made my irreparable gaffe, I had the freedom to wander through Tirana, which I noted was a disappointingly uninspiring city in its appearance. This was more because of the old than the new. The new was indeed commonplace: a pattern of broad, even grand, streets lined with old Italian-style buildings, with a boulevard wide enough to take several lanes of traffic, which for 80 percent of the day was completely empty.

The desolation of the streets was frightening. At every intersection stood a vigilant traffic policeman in a white uniform, ready to direct a flow of vehicles that never came. Once every five minutes, perhaps, an old green truck, passing rarely on its own, would appear rattling and groaning down the street; the traffic policeman would snap to attention as it appeared on the horizon and would vigorously wave the sign he held in his hand, having no sign of opposition. At even rarer intervals, a dark “Zim” sedan, with large curtains, would appear, moving on some mysterious official duty. Throughout Albania today, as I was officially told, not a single private automobile existed.

Down the “New Albania” Boulevard, below Skanderbeg Square, where the large statue of Stalin shone from the illumination of lamps and banners reading; “long live” the chief leader Enver Hoxha, who led the workers’ state, Tirana seemed to have fallen to a crossroads, where an ever-increasing poverty reigned. There, where tinsmiths hammered their pots and cauldrons, strolled those poor Albanians, who were never thought to detach themselves from that folkloric and also religious way of life.

Half the people dressed in the pale style of a normal urban proletariat, but the other half, without any kind of self-consciousness, poured forth in the white, Macedonian-like attire, the embroidered xhubleta, and the gigantic broad trousers of the Muslim highlander. Albania must be one of the few remaining countries where what is known as the folk costume is actually worn by the peasants.

These seemingly handsome and fierce men had a peculiar and charming habit: that of holding flowers in their mouth, as others wear buttonholes. Many times one would encounter individuals with wild visages, with dark mustaches, from whose contemptuous lips protruded a rose or a sprig of marjoram. Even the vigilant and weary soldiers redeemed their attention with this strange habit. Once, outside Tirana, I saw a blurred guard at a wire fence, which had thrust a bunch of field flowers into the muzzle of his “Carbine.”

The first and very serious problem I encountered was that of communication. The Albanians speak a language that seemed to me very difficult and insurmountable; a kind of tortured Turkish with severe Slavic complications, in no way to be grasped overnight. It has an alphabet of thirty-six letters, with seven vowels and twenty-nine consonants.

The words for “yes” and “no” are po and jo, but this should not make anyone underestimate its complexity. I soon discovered, for example, that Albania, in its own language, does not call itself Albania at all, but “Shqipëri,” which somehow seemed unreasonable to me.

Although Albanian may be surprising, few people seemed to speak much more. Since our tourist group originated from Germany (and was mostly German), the translator provided spoke German, which was not useful to me, as my German is not at all good. I did not meet anyone who spoke a word of English. When my rebukes occurred, involving a rather harsh and complicated discussion, it was translated from Albanian to Russian, from Russian to German, and from German to French.

This small local difficulty should be better mentioned now, as it completely changed the character of an already somewhat shapeless expedition. I could see that the Albanian authorities (which in fact meant everyone we came into contact with) were shaken by the transparent professional nature of our tourist group, although it seemed to me that their reactions had been unexpected but courteous. Therefore, one day after our arrival, I sent a very short telegram to the newspaper in London, to which I was contributing.

I sent it in the customary way, through the hotel desk, and while its main purpose was simply to give my address, I thought it could do no particular harm if it was laid out in terms that the People’s Republic of Albania could not oppose. Above all, there was news value in the arrival of Western foreigners in Albania, and this was my starting point. “This small, proud, isolated Republic, which has bravely defied the East and the West,” I wrote, “has opened its doors,” etc., etc. If I had any doubt about the wording, it was that it was conciliatory to the point of being complete; it might win the contempt of any Albanian censor for its way of life.

What I had not anticipated was their extraordinary reaction. I was occasionally summoned by a small group of taciturn functionaries, but clearly in a state of pronounced hostility. After a multilingual communication, I was given to understand that my telegram had been deemed unpleasant, unfriendly, and contemptuous, that it had undertones with a fascist spirit, which was an intolerable violation of my status as a visitor.

This seemed so astonishing to me that I concluded there must be an incomprehensible misunderstanding. What specifically did they object to?! The terms describing the People’s Republic of Albania, of course, were quite offensive. But, I protested with some incredulity, the words I used were not generally considered hostile; “guarantor,” “small,” “proud,” “isolated…”! That is what had scandalized them, the word I had used: “isolated!”

Who else but a “Western lackey” would use such a bitter, such an inaccurate word?! Already feeling deep in Alice in Wonderland territory, I protested, saying that the word “isolated” was not a term of reproach. Why, I said, not many years ago, in the early days of the war, we in Britain boasted of being isolated. “Right,” they said, “and so you probably are still, but Albania is not!” The term used is cruel.

By this time, the conversation was moving toward the absurd. “All right,” I told them, “you are right, so I accept that my message was ill-judged.” “Not at all,” replied those who were surveying and controlling me; all that had happened was that the Post-Telegraph employees who read the telegram, with their vigilance, were so indignant at its text that they refused to transmit it. Furthermore, I’d better not get caught trying to send any more telegrams, good or bad. And moreover, they had actually put an exit visa in my passport and did not care at all how soon I used it.

At this point, however, what, from their point of view, was a very embarrassing and shameful obstacle emerged. It’s all well and good to make the grand gesture of opening the front door and saying Begone, but the climax loses something of its drama when it turns out there’s nowhere to go. Tirana is far from being the traffic crossroads of Eastern Europe.

Its airport sends out about two planes every fifteen days. The border roads were cut, and the railway did not function. Since they did not throw me to the end of the pier, there was no practical way to get rid of me for at least ten days. The relevant officials seemed to appreciate this very belatedly and left, after a few cold and courteous handshakes all around, to review my situation.

So I remained alone for another day, while the competent authorities of the People’s Republic of Albania reflected on the next step they needed to take. It seemed to me that my situation was not at all annoying. For a start, I asked if our tourist group could take a look around the University of Tirana, and this was agreed to with surprising readiness. The University was, in fact, the most imposing building in the city and was described with some pride as a monument to the People’s Democracy that had been established in this country since the end of the War.

It was, in fact, like most of the real estate in Tirana, a monument to the opposite side, built about twenty years ago by Mussolini, as the Casa Fascista of the occupying forces. Nevertheless, it was a beautiful matter, and the students were a strong and likable crowd. They drifted in and out of our group, with a kind of vigilant curiosity; for me, it was like being in Moscow fifteen years ago.1

Indeed, there was a large part of Albania that was like post-war Russia, before the spirit of Geneva opened so many tongues and turned contro2lled sincerity and kindness into a civic virtue. It was as if China had been seven years ago, when I had found in schools and universities, communities of young people consumed by the impulse to communicate, but completely inexperienced in the technique of doing so.

The main problem in these circumstances, besides the language and the permanent presence of translators, is that the only questions that come to mind are the awkward ones. In a kind of Franco-German language, I began, minimally, to penetrate, asking them: “Why do you personally feel this aversion to the Soviet government?” It was a question, but it seemed clear that Khrushchev had somehow promised the Greeks to support their claim to Northern Epirus; w3hich for them was Southern Albania. He had agreed to support Tito, and everyone knew what he was.

When Khrushchev had visited Albania in 1959, not hiding his disappointment with what he was seeing in this country, he called Albania a “market garden” for citrus and fruit growing. “Comrade Khrushchev,” they said, “had betrayed the basic spirit and ideals of Marxism-Leninism, scorning the national right of free Albania to become a proper power.” Furthermore, no one seemed able to see that for the moment, being practically alone in the world, were they not indissoluble allies with the largest nation on earth, the Chinese?

But, I asked, while the Chinese were a large and powerful people, weren’t they very far away?! “No,” they said, “it wasn’t too far!” Wasn’t it inevitable that sooner or later, this small, unyielding nation would have to reconcile with someone, even just to survive?! No, it wasn’t, they said. The debate was initially without much mutual accusation, but soon became very heated.

The next day, they put us all on a bus, took us down to the seaport of Durrës, and left us there. I would not see Tirana again.

Durrës

DURRËS, Durazzo of the Italian days, is one of the truly ancient places in Europe. It was Epidamnus of the Greeks, Dyrrachium of the Romans. It had been the capital of the Illyrian dynasty of the Taulantii; it had been the very landing place from which the Romans colonized Eastern Europe, the gate to the Balkans. Almost every foreign hand had grabbed Durrës, developed it, plundered it, and left it, from the Bulgarians, Serbs, Ostrogoths, Spanish, Venetians, Turks, and Italians. Now it seemed like no one wanted to bother with it.

As it turned out, I would see little of Durrës. For an hour or two, we stopped on the road and drank ouzo in a cafe near the Port and walked toward the massive, overgrown walls of the old Byzantine castle. A long line of little girls walked up the street to school, all dressed identically, in rose jackets, each child holding firmly to the edge of the one in front. The shops were extremely gloomy, offering for sale few newspapers, magazines, and books with Marxist-Leninist content, as well as dusty sweets. Almost all the food seemed to be sold in MAPO (the Albanian equivalent of the Russian network of Gastronom stores); it seemed to consist mainly of fruit and canned fish.

Only two things were surprising. As the conductor urged us back onto the bus, I heard a slight lament in the air, a cry like that of a muezzin, and when I looked up, it was a muezzin; high on the minaret of the great mosque of Durrës, he was calling the faithful to prayer, in the seven names of God. It was clear that here, at least, as in the Muslim Soviet Republics, communism was reconciled with Islam. (I later discovered that both in Durrës and Tirana, the Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches remain open and gather righteous congregations, and priests and popes are tolerated, if not encouraged.)

The other momentary shock was to go to a dark and gloomy shop window and see, by chance, among the postcards of Enver Hoxha, Lenin, and Stalin and all the other small members of the Eastern Pantheon, the familiar unholy face of the only one as well: the familiar tousled hair of what was unnecessarily named; “Brigitte Bardot.”

About five miles outside Durrës, stood the new beach hotel called “Adriatiku”. It was one of several hotels facing the sea in various conditions, half-finished. All had clearly been erected by the Russians to be used as a resort, and when the rift came, they had been abandoned, just as the embassy had been abandoned. Only the “Adriatiku” was functional, and of its three hundred rooms, the only ones occupied were ours.

It was designed in what might be called the Soviet Black Sea taste, meaning the architecture was of an elaboration and grandeur that could only be justified by its completion in costly and luxurious materials. However, it had been rushed and in a trail of traces; instead of fine wood and rich marble, there was gypsum board and grated cement; in the spacious hall, evergreen plants grew from oil drums painted green. In my bedroom, the sofa was positioned in such a way that to get into bed, the wardrobe had to be moved, and to open the wardrobe, the bed had to be moved. The overall effect was irritating.

Below the hotel terrace was the beach that I would come to know so well. By the standards of beaches everywhere, the Durrës coast was beautiful, stretching wide arms north and south along the calm Adriatic. It was the kind of beach made to be photographed in color for a holiday brochure, gay with umbrellas, filled with girls in decorative and minimal costumes, lively, with waiters cheerfully carrying trays of fizzy drinks. Today the beach was deserted, a stretch of uninhabited sand, as I have ever seen outside the remotest areas of West Africa.

No gay umbrella broke that flat expanse of ochre, no girl in a bikini sat on the hot steel chairs of the terrace. A waiter spent most of his time hiding in the dark interior, emerging only after emissaries had been sent to drag him from his meditations. For miles and miles, no one seemed to be visible, except for the handful of anxious tourists and the occasional policemen, who humorously strode along the sand, sweating and shivering under the powerful sun. Memorie.al

To be continued in the next issue