From Agim Musta

The twelfth part

Memorie.al / On the fourth anniversary of the passing away of the well-known historian, researcher, writer and publicist Agim Musta, (July 24, 2019), former political prisoner, his daughters Elizabeta and Suela, gave him the right to exclusivity for the publication, by the online media Memorie.al, of one of the author’s most prominent publications, such as the ‘Black Book of Albanian Communism’. This work contains numerous data, evidence, facts, statistics and arguments unknown to the general public, on communist crimes and terror in Albania, especially against intellectuals, in the period 1945-1991. The publication for the first time of parts of this book is also the realization of one of the bequests of the historian Agim Musta, who, from the beginning of 1991 until he passed away, for nearly three decades was engaged with all his powers, working to raise collective memory, through book publications and publications in the daily press. All that voluminous work of Mr. Agim Musta, concretized in several books, is a contribution of great value to the disclosure of the crimes of the communist regime of Enver Hoxha and his successor, Ramiz Alia. A good part of the publications of Mr. Agim Musta, is also translated into English. Thanking the two daughters of the late Musta, who chose Memorie.al, to commemorate their father, from today we are starting the publication, part by part, of the “Black Book of Albanian Communism”.

Continues from last issue

– Forced labor camps-prisons, everywhere in Albania-

(1945-1991)

Roads washed with tears

The streets of prisons and slave labor camps were washed with tears, for half a century, by our good mothers and sisters. Crouched with the rafters on their backs, they traveled towards Maliq, Beden, Tërbufi, Burrel, Bulqiza, Spaç, Qafë Bari…! And they walked and walked without stopping. And where did not step their foot?! They endured with clenched jaws insults, threats, humiliations from devils with red stars on their foreheads, but they were not afraid and never retreated. They were not repulsed by storms, or by downpours, or by the frost of winter and the scorching heat of summer. They often traveled on foot, because the drivers followed the insurance orders, so as not to take the mothers and sisters of the “enemies of the people” in their cars. The mass of pain gathered in their chest, they vented with tears in the streets of the prisons.

They shared the morsel of the mouth, to bring us to the places of suffering. They suffered spiritually more than we who were inside the bars, but they covered their pain, with fake smiles and the hopeful words they said to us. They stood for hours, with trembling hearts in front of the iron doors of the prisons, and often stayed up until the morning, waiting, without closing their eyes. When they returned, they were more poisoned than when they came, and they washed again with sighs and tears, the accursed streets of the prisons. Today, many of them are no longer alive. They died longing, because they did not have their sons and brothers by their side, to give them the blessing and tell them the bequests. Every time I travel through the homeland, I see visions of our mothers and sisters, who seem to me wet with their tears. O good Albanian mothers! How much you suffered, in the years of communist hell.

A. Kozara forced labor camp

The political prisoner Muhamet Hoxha tells about the Kozara camp. “It was the spring of 1948. I was sentenced to 10 years of deprivation of liberty, in Gjirokastra prison. One morning, earlier than usual, we were taken out of bed with a big bang. We were lined up one by one, from both sides of the corridor and they tied us up with handcuffs and chains. Those who were too old, they left them in prison. Surrounded by dozens of armed policemen and soldiers, they took us to Çerçizi Square. There the cars were waiting for us, where we barely got into them. Where are we going? Were we going?! No one knew! You couldn’t ask the policemen, you might get a piece of wood as an answer. When they started us, we weren’t even allowed to do our personal needs. Some prisoners tried to be restrained, but they didn’t they could hold out for a long time. They began to defecate in their trunks. The wind was unbearable. After a torturous road, we reached the Kozara camp. The camp was shaped like a square, surrounded by barbed wire three meters high, with machine gun emplacements and of searchlights, with double beds made of uncut boards, with an open water well, close to the prohibited line, at one end of the yard and 15 m. away, a hole in the shape of a parallelepiped, with some beams thrown over it, which would serve as a toilet. The water, of the so-called well, was full of microorganisms, even worms. Taking water from the well was done with ropes tied with rope.

Surely, the sewage from the toilet filtered underground into the well water. The fact about this was diarrhea, which did not leave us as long as we stayed in the Kozara camp. The job was over an hour away from the camp. Initially, the prisoners worked, although the camp command set high work rates. Each prisoner had to dig 10 m3 of earth, or transport it by wheelbarrow, several tens of meters away. As the days passed, the prisoners’ strength declined from exhaustion, while work rates increased. If you remained two seconds without working, the policeman would hit you in the back of the head and the prisoner would fall to the ground. The friend did not dare to help you, because he suffered worse than the one who fell. The terrain was hilly and the channel was 10-12 meters deep.

During the summer, the thirst was tremendous. The prisoners at work, to quench their thirst, drank the murky waters of the canal, with whatever filth was in it. The food was very bad. In the morning, boiled water with a little sugar, which they called tea, at lunch and dinner, a soup, where the grains of rice or buckwheat could be easily counted. The bread ratio was 600 grams of corn bread, cooked as for pigs. While working, hiding from the eyes of the police, the prisoners ate some white roots, which they found while digging the ground. The camp was completely isolated from outside life. Meeting with families, receiving packages and money, and entering newspapers were not allowed. The water of the camp’s well, one day, turned red from the blood of a Dibra boy, killed by the police guard, because he had dared to fill water from the other side of the well, which was near the prohibited line. At lunch, when we lined up to get the soup, the camp commissar addressed us with these words:

“Today, one of your friends tried to cross the wires. He received the punishment he deserved. This fate awaits all those who will attempt such a thing, or dare to violate the rules of the camp”! Life in the Kozara camp was a constant torture. Hard exhausting work, daily beatings, constant hunger, indescribable filth, diseases of every kind, languishing without any medical aid, and complete isolation from outside life. I remember Foto Tomidhi, a former trader from Delvina. He began to lose his physical strength, until he no longer had the strength to walk. Fellow sufferers took him in their arms to take him to work. When they came to the workplace, they left it on the ground. He didn’t have the strength to get up. He had turned into a living corpse. The policemen were kicking him, shouting: “Get up, dog! Work, we’ve taken his soul!” He looked into his face with a look that would tear his soul. They kept kicking him until he lost consciousness. When the work was over, his friends would take him back in their arms and take him to the camp.

This work continued for several weeks, until the Foto desert gave life. The camp command used the half-dead man as a symbol to scare the other prisoners. The gravedigger of the camp was appointed Elmaz Libohova, a noble, cultured and virtuous boy. He had the task of gravedigger in addition to the heavy work he did together with fellow sufferers. He took the corpse in his arms and, accompanied by 2-3 armed policemen took it a few hundred meters away from the camp. There he dug a shallow grave, according to the orders of the police, and placed the corpse, covering it with a little earth. Most of the graves were discovered at night by jackals, which were abundant in that area. One day, they tied Elmaz to the post in front of the canteen, keeping him for 24 hours under a rain and hailstorm, which also broke the walls of the silos. Everyone gave up hope that we would find him alive the next day. To our surprise, Elmazi remained alive. They removed the 20-kilogram drum from his neck, untied his hands from the barbed wire and sent him to work, without the bread ration.

His friends held him by the arms. He was waiting for you to eat and many of us thought that Elmazi would soon go to those you had buried. Moral strength and young age saved him from certain death. When a prisoner died on the job, the officers ordered that he be buried in the bottom of the ditch. I remember Baba Shehu of Picari. He was the son of Sheh Ahmet Shkodra, located in Teqen e Picari of Gjirokastra. He became extremely weak, but diarrhea gave him the last blow. He could not hold his stomach and soiled the bed and the camp yard, running to the bathroom. He cleaned himself with the rags he was wearing. After a few days, you had consumed all the rags and remained naked, like the wild people of the Amazon jungle. No one mocked him, no one insulted him. Only the guards laughed when they saw him in that state. He died after a few days. So, naked, Elmazi took him in his arms and buried him with the others. But some of them defied death.

One such was the Jew Tovi Jamtovi, from Delvina. He was fat and wore a pair of thick-rimmed glasses. Every time the police kicked him, his glasses fell to the ground in shock. He never learned to use the pick and shovel properly. Although he was more tired than the others, he gave the least yield of all. For this, it had turned into a shooting range, for the kicks and noses of the policemen. He lost so much weight that his stomach turned into a shirt that hung below his knees. Despite all the torture he suffered and the physical weakening, he remained alive. Those who fainted at work were kicked by the policemen along the escarpment, until they ended up on the bottom of the canal. Those who were not mentioned when the working hours ended, they were covered with dirt. Due to the impure water and lack of minimal hygiene, dysentery claimed many prisoners’ lives. It happened that 2-3 people died a day. Perhaps the diarrhea turned into cholera, but to our surprise, when we had lost all hope that we would remain alive, it disappeared from an omnipotent and invisible hand that no one could explain. How many died in the sick camp of Kozara?

No one knows for sure, except for Elmaz, but he is no longer alive and the number of those unfortunates will remain unknown. It will remain an “iks”, like many other “iksa” and “ipsilon”, in the half-century drama of the bloodthirsty communist regime. By mid-November, the trucks came to take us to the prisons. Few were those who had the strength to climb them. We were no longer who we had come seven months ago, but their shadows. The motorcade started. We sat thoughtfully with our heads down as if we were going to the mortuary. When we got down to “Cerçizit Square”, we were unable to walk; we were crawling on the stone streets of the city. Before we reached the iron gate of the prison, two people died. After a week we were allowed food and meetings with the families. They didn’t know us and were confused when they saw us. We had transformed so much in seven months. In the foundations of reclamation works, built with the blood and sweat of tens of thousands of prisoners, in the darkest period of our nation’s history, there are hundreds of skeletons of innocent people. On that work, on that sweat, on that blood, on those bones, Enver Hoxha and his caste raised their shameless and satanic glory”

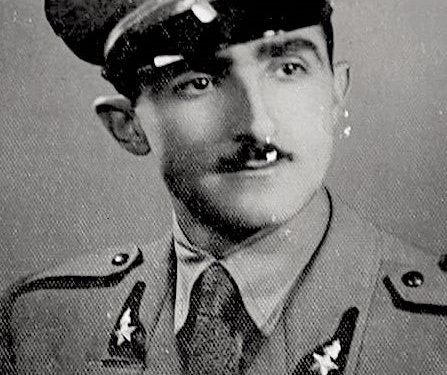

B. The genius of torture, “The Black General”, Nevzat Haznedari

I knew Nevzat Haznedar as a face since 1947, when he, as a military prosecutor, had become lenient in the trials that took place at the “17 November” Cinema in Tirana, against the so-called “hostile groups”. His large head, like that of the old Slavs, his strong but slightly stooped body, his steel-colored eyes that pierced even the concrete, and his hands, like the paws of a Siberian bear, stuck in my memory. . I was told that he came from a family of ruined beylers of Leskovik. During the thirties, his father used to frequent the cafes of Korça, in a miserable condition, until he died on the street and was buried by the municipality. At that time, Nevzat continued the “Normal” of Elbasan, with a state scholarship. In “Normale”, his friends called him “wild”. His favorite literature was novels with torture. In 1938, after finishing the “Normal” of Elbasan, he was appointed a teacher in Postenan village of Leskovik. His former students say that they got away with beatings when the teacher threatened them even for the smallest mistakes. After he could not make a career in the Fascist Party, during the period 1939-’42, he took off the black shirt and put on the red shirt, becoming one of the leaders of the Communist Movement in the sub-prefecture of Leskovik, together with Kiço Kasapi and Ali Glina.

In the spring of 1943, he shoots Gaqi Tasho, along with his son, Petraq and Petro Tasho, in the gorge of Postenan, for the sole fault of having distanced themselves from the National Liberation Movement, when they realized that it was being led by the Communists. . At the end of 1944, Muharrem Rusi, former mayor of Leskovik Municipality, a man honored and respected throughout the province, was executed. Right after the establishment of the communist dictatorship, Nevzat was appointed the Military Prosecutor of the Korça District, where he became famous for his exploits and misfortunes. Participates in the execution of the group of Maliqi’s engineers in November 1946, throwing the rope around the throats of Abdyl Sharra and Kujtim Beqir with his own hand. Mr. Ali Selenica, a lawyer, who died in Burrel prison in 1963, while serving his sentence, told me that at the beginning of 1945, when he was working as a lawyer in the city of Korça, the communist military court, with prosecutor Nevzat Haznedari, gave every day “in the name of the people”, 10-15 death sentences. Most of the convicts were illiterate intellectuals and peasants who had gone with the forces of the National Front.

The trial made no distinction between the real guilty and the innocent! The sword of the communist dictatorship in the hand of the criminal Nevzat fell cruelly on the heads of innocent people. Even the simplest legal norms were violated. Such trials did not take place even during the time of the Inquisition and not during the Ottoman rule. No matter how patient and cowardly you were, you were revolted by this cruelly violated “justice”. “I revolted – Mr. Selenica, – when Nevzati requested the death penalty, for a ballist from the villages of Devolli, who was mute. He accused him, among other things, of being a ballistic devil, of having developed propaganda against the National Liberation Movement”. Zoli Ali, as the defendant’s lawyer, said that the accusation against his client was as absurd as it was ridiculous, since the accused was mute and could not have committed the crime of agitation. Nevzat had insulted the lawyer with the dirtiest words and had accused him of being a fascist and for that reason fiercely defending the enemies of the people.

Mr. Ali Selenica retorts with prosecutor Nevzat, saying that he was a fascist, something that was known by the entire Korça district. Captain Nevzati is furious with anger and demands the suspension of the court session. Mr. Selenica, the lawyer, after an hour, saw himself handcuffed in a dark cell of the Korca Security. After three months of torture, carried out personally by Nevzati, Mr. Ali was sentenced to life imprisonment as; “enemy of the people”, while his two sons, to escape persecution, were killed trying to cross the Albanian-Greek border. Within 11 years (1945-’56) taking hundreds of people to the other world, executioner Nevzat reached the rank of general, becoming a symbol of state crime. There was no arrestee for “hostile” matters that Nevzati had not interrogated and “caressed” with his paws.

There was no prisoner who had escaped without bleeding from an encounter with him. Even the little executioners in the investigative offices, in the prisons and concentration camps, stood before him, like chickens. He passed through his hands, with thousands of victims, from simple villagers to prominent intellectuals, ministers, generals and members of the Political Bureau, ending his career with the “group” of Beqir Balluku. In 1954, when the political prisoners in Camp no. 4 in Tirana, they tried to open a tunnel, to escape from the communist hell, “enverian justice”, fell mercilessly on the heads of those unfortunates, who wanted to gain the unjustly robbed freedom. More than 20 people were sentenced to prison terms serious and 4 of them: Abdulla Bajrami, Mark Zefi, Isuf Velçani and Zyhdi Mancaku, were executed in the cells of the old prison of Tirana, by the executioner Haznedar, cracking their skulls with an iron crowbar. The personal meeting with this “Lucifer”, of I met him in an investigation room of the Tirana prison, in April 1962. He was accompanied by 3-4 senior officers, who were standing close behind him.

Handcuffed, they sat me on the defendant’s concrete chair, while General Nevzati, with a ruler in his hand, asked me what I had discussed with his bailiff, teacher Fatmir Berati. I told him that with Fatmir, I had been a colleague at the “50-anniversary” school, of the Textile Factory, and I was not close enough to discuss political issues with him. He began to shout loudly and turned to the officers, telling them that we should be lynched, what to do with Comrade Enver, who said to apply the law. “These bastards wanted to reform the Social-Democratic Party, which Musine Kokalari could not do in 1946, and they will suffer worse than her.” With an outstretched arm, as if he were going to split wood, he put a ruler on my shaved head. My eyes went dark and covered in blood; I fell out of the chair unconscious. When I came to, I saw that I was in my cell, with a dirty cloth tied around my head. Capt. Koli, who was noted for his gentleness among the cell guards, brought me a handkerchief wet with water to wipe the congealed blood from my face and clothes.

I knew that Fatmir Berati was friendly with Nevzat, but the latter did not talk to him and wanted to bring him in, because Fatmir came from a family affected by the communist government. This was the first and last meeting with the chief executioner of the Enverian dictatorship, the “Black General”, Nevzat Haznedari. In 1959, Nevzati reassembled the “Leskovik Group”, with people who had escaped alive after serving their sentence, from the “Leskovik Group”, from 1947, adding other unfortunates to complete the standard number; 20. This time, the operation was carried out by the first deputy minister of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Mihallaq Ziçishti, with his assistants, Rexhep Kollin and Nevzat Haznedari. Vangjel Stefan Cini, who was able to escape alive from the “Leskovik Group”, told me with a trembling voice and frozen face about that terrible day of torture.

The arrests were made at 02.00 on March 30, 1959. 19 people were arrested within 1 hour, after the number 20 on the list, Kolaq Kozmai, had died, and for this they removed a severe warning to the micro-criminal Tare Isufi, Head of the Department of Internal Affairs of Kolonje, who had not notified the department about his replacement in time. “They tortured me in the most inhumane way. They left me only my underwear; they tied my hands and feet with handcuffs and a chain around my neck. Tare Isufi dragged me to the floor of a torture chamber, while Nevzat, with the heels of his boots, hit me as much as possible, my fingers and toes. I used to faint, they threw buckets of water at me to mention me, and when I was mentioned, Rexhep Kolli and Nevzat, they told me to affirm that I was a Greek agent, otherwise they would they took my soul little by little. Then Nevzati changed the torture, squeezing my throat and in the last seconds of breathing, he released me, throwing tobacco smoke into my mouth, which caused me a terrible cough, which I don’t like forgotten as long as I’m alive. After 3 days of torture, they took me to the Starje River, where they had opened a grave about 50 cm deep. They put me inside and Nevzat directed the white “Smith” with a mill, on the flower of my forehead. Instinctively I closed my eyes, and he shot in the air, and then ordered me to be taken to Tirana, where he would remove my flesh with pliers.

After 10 months of torture, when we accepted everything that was served to us by the investigators, as per General Nevzat’s scenario, they took us to the military court, with the exception of Thanas Lula, whom they could not break and they were afraid that he would reject with disdain the fabricated accusations, which could give heart to the other bandmates as well. During the court sessions, Nevzat, in the eyes of the judges, threatened us constantly, telling us that he would send our heads to Leskovik in a pan, like the head of St. John the Baptist. After four court sessions, they were sentenced to death; Mihal Cini, Thoma Buda, Janaq Ruçi, Hajredin Gega, Shahin Hajdari, Kiço Kuqoshi and Thanas Lula (in a separate session), who were executed after a few days, while Xhevat Zerja and Musa Shemja, died in the hands of the investigating executioners. Three others died while serving their sentence and all the others died after being released from prison, with the exception of me, who managed to see the birth of democracy and bring to light the crimes of the communist dictatorship”.

For every “hostile” group that would be arrested in Albania, Nevzati would invent something new in his torture. For Teme Sejko’s “conspirators”, he used “bee hives”, for Devolli’s group, “iron lockers”, those who were going to be shot, before breaking their skulls with iron crowbars. Salt on open wounds, kerosene ampoules, putting feces in pits, electrocution, squeezing the genitals, putting in barrels of ice cubes, hanging upside down from hangers, pumping out the anus, he called out of fashion, and worn out from him. They had sent him for experience in the Soviet Union and in China, but it is said that the Chinese “friends” left him speechless, from his Albanian experience. They said that they had nothing to teach this genius, in the field of tortures and thanked him, giving him as a sign of gratitude, a book with sketches of tortures, which were used at the time of the Min dynasty.

In 1974, the dictator Enver Hoxha summoned Nevzat from Elbasan, where he served as the head of the Internal Affairs Department, to investigate the “rams of the army”. The souls of Beqir Balluku, Petrit Dumas and Hito Çakos, know what they have taken away from this satan, until yesterday their friend and companion. It is said that against them, he used the tortures of the Min Dynasty, elaborated as he knew. With this, the investigator ended the “glorious” career that the Albanian nation has produced. The dictatorship gave him a villa on “Tefta Tashko” street and a special pension as a reward. He died suddenly and people say that he was poisoned by order of the dictator, to eliminate a living archive of crimes. Surely his soul is in the ninth circle of Hell. Memorie.al

The next issue follows