By SIMON MIRAKAJ

The first part

“Camps under the shadow of Tomorri, 44 years of internment”

– Memories –

Entry

Memorie.al / I put these memories down on paper after a long period of hesitation. This is probably because the subjects were always fresh in my mind, which followed me mercilessly during the years after the fall of communism. But there comes a moment – when time takes its course – and the images of horror and suffering came fading to me – almost the suffering passed into oblivion. Then I decided to repeat the most impressive events – first in my mind – until they took the form of these narratives. As dim as these accounts may seem – they create the idea of the harsh reality and misery of the camps.

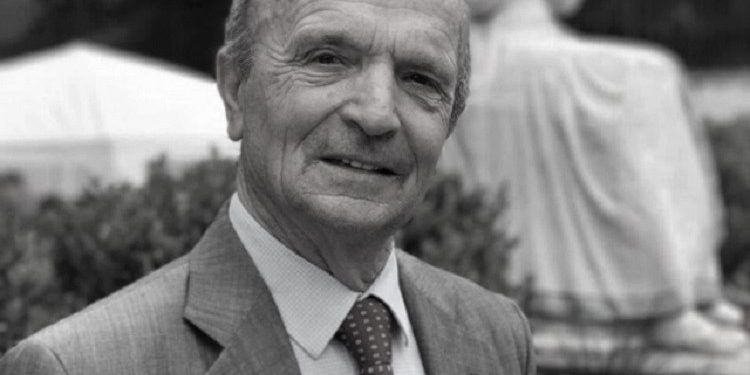

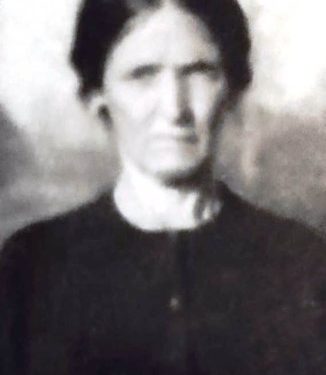

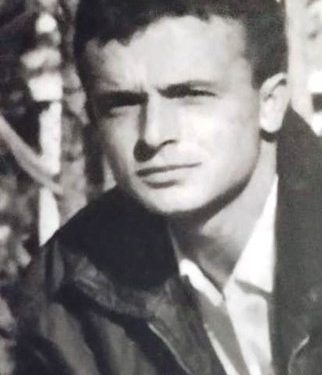

The camps where our families suffered punishment – surrounded by barbed wire like Tepelena or other places of suffering like Shkodra, Berati, Gjaza and Savra – still serve to recreate Albania’s time in the dictatorship between 1945 and 1989. Many of the stories in regarding the first years of life in exile, I have kept them in my memory during the confessions of my mother Kunes, who kept alive the memory of my brother, Pal, as one of the leaders of the anti-communist squads, in the north in the years 1944-1951, who died in New York in 1978, without ever seeing him.

When the Mirakaj family and I were released, it took time to perceive life outside the camps and build it. In these stories, I have tried to bring themes that, in addition to persecution, are related to youth and love. At this time one starts and fantasizes about freedom – no matter how poor. But when dealing with the most impressive part of the age of love – writing becomes difficult.

I have tried to convey this aspect of the class war between the internees and the “free” in Lushnje. A multitude of young people have fallen prey to the dictatorship of the communist system that imposed political selection, turning the couple’s natural connection into a taboo.

Tirana December 2023

THE FIRST PART

THE LIFE OF THE PEOPLE IN THE COMMUNIST CAMPS CONFESSIONS

Newborn in Shkodër. Our family was in exile for 3 decades, we were already in Gjaze, Lushnje. Nana was in the house that day and had received a report while I was sitting next to her holding my father’s photo. My first internment from Shkodra when I was two weeks old in the Berat camp happened in July 1945. I still didn’t understand the truth of my life in the camps, that’s why I asked my mother.

Mother, – I say, – how did you get this man without hair? She laughed out loud. Then, with my father’s picture in my hand, I asked him: Mom, when was the last time you were with your father? She sighed, took a deep breath: Son, with father now, we parted early. The partisans were approaching Iballa, then your father told us: – Get ready soon, we will close the house and escort you to Shkodër!

That’s what we did and set off on foot with all the children. I was pregnant with you. We walked all night, when we got close to Fush-Arës, we rested. Father hugged the two children, Sokol and Lajden, and greeted me as well. Now the car comes to you and starts you in Shkodër. He turned his head and climbed the mountain. I say: Paul, where are you leaving me? I’m pregnant! – without turning his head he said: You are not alone!

I speed up my steps and I didn’t see him anymore; this was the last time I was without my father. I arrived at night in Shkodër to a hill in front of the Markagjon tower. I was born in that house on June 7, 1945. After a month, a car with soldiers came, shouting: Come quickly, get in the car!

They barely let me take a couple of cloths, to wrap myself in, a blanket and a quilt. The car that fills up with other families, such as that of Nik Sokol, Markagjon, Destanishte, etc. They have sent us to Berat. When we arrived, they put us in an abandoned house that they called “Pasha’s Spy”.

After two or three days, they sent us to Kala. The police were watching us. They gave us 400 grams of dry bread. During the day, my mother and the other internees would go to work in Kuçovo, with a bunch of sunflowers. She took me with her because I was breastfeeding.

Nana had a mark on her pelvis where the policeman had hit her with the toe of his shoe when he saw her giving me a drink. I was listening and started to cry, my mother kissed me and said: – Don’t cry, you are now a man. Nana also remembered several merchant families, who came at night and brought us food, such as; cheese, yogurt and butter. We told them: Don’t fall for us, because we don’t have money to give you!

No, we are not bringing you to sell, but to feed the children. Better to eat your children than to have the communists eat us. Those families were Haxhistasa and Baballek. We are grateful to you, for life. Out of fear, they brought us food after dark.

When relations with Yugoslavia broke down in 1949, we were sent to the Tepelena extermination camp. First, they put us in some silos in Turan, and after a few weeks, in the Tepelena camp.

IN THE TEPELENA EXTERMINATION CAMP

1949-1954

After the break with Yugoslavia, comes the transfer of internees who were in Berat, Kuçovo, Krujë to Tepelene. First, they send us to Turan and Veliqot in Tepelena, they shelter us in goat stables, where they suffocate fleas and dirt. After a short time, many children lost their lives from lack of food, as well as from the inhumane conditions in the cattle sheds.

After the mass deaths of children, they removed us from Turan, sending us to the Tepelena camp. I went to that camp when I was 4-5 years old. The camp consisted of several barracks which were built by the Italians in the Italo-Greek war. In one of the barracks, only the walls without a roof were left, where our mothers bathed us in summer and winter.

I still remember our cries from the cold. There were approximately 2500 or 3000 internees in the camp, from different districts of Albania, the camp consisted mainly of women, children and old people.

The camp was surrounded by barbed wire, outside the perimeter was the police command, the camp commander was lieutenant Haki Pogaçe, after lieutenant Haki, came lieutenant Ahmeti, marshal Tomi, aspirant Syrjai and captain or, the horror of the camp, captain Selfo. Inside the camp was the infirmary and the bakery, outside the wires was the police garden.

The bread was 600 gr., for those who worked and 400 gr., for the unemployed, the food was divided from the cauldrons that sometimes-had grains, that a microscope was needed to find any grains and semolina with worms. It was happiness when our sisters, Lajdja and Klorja, brought us pear, berries that they collected on the way when they returned from work, or some gavage with whey, that the Tepelena villagers gave us from the dairy.

The girls worked cutting wood in the mountains, for the camp police and for the Tepelena Internal Affairs Branch, from one time they were sent to Turan, to carry manure on their backs, for the garden of the camp police command.

The sisters, together with their uncle’s wife, Gina, separated them from us and sent them to the Brick Factory in Valiaas, when they were not yet 15 years old. The barracks had a stove and people pushed each other to bake the oak logs, which were food for pigs, hunger was present among adults and children, who shouted at night: – I want bread, mother.

What makes this camp more terrifying is that in its yard, approximately two hectares, the shells of the Italo-Greek war were found and the children were forced to collect and stack them like bunches of grapes, there were times when the mothers, to boil the clothes, they lit the fire and put the cauldron, which exploded from the mine below, blowing up the children, who were nearby to warm themselves. As I said above, the police had a garden where they planted greens, melons, etc.

The internees worked the field, but the fruits were eaten by them, in the summer when the melon was ripe, they plucked them and sat down to eat, the children stretched their hands between the wires, hoping like children, they would get a piece of melon, but they didn’t. only they didn’t give them, but the skins were eaten well and then thrown to the children, they were happy and laughed when they saw the children, who scrambled to catch the watermelon skins thrown by them. Two children, no more than 9 years old, Liman Koleci and Zef Mirakaj, from hunger, crossed the wire fence and climbed the hawthorns to collect some red berries that were dropping, to eat them, when they were getting ready to enter the camp.

He looks at the catcher who catches them and ties them to a pole, outside the wires near the tap. They kept them tied to stakes all night, even though they did not stop crying. Zefi’s mother, my mother’s sisters and us other children, stood inside the wires, telling them not to be afraid, because here we are. He was crying as he said; “I’m being eaten by a witch”, he dreamed, while he slept tied up and the wind blew the tap water in his face and he woke up again.

Every day there were deaths of children or elders, 300 children died in the camp, but how we got out of this camp alive, I don’t even know! The graves were moved three times and today they are no longer found, because the last time they were placed on the edge of the Bênçë river, which overflowed in the winter, taking everything with it!

The Tepelena camp was closed in 1954 and all the internees were distributed to different camps in Lushnje, such as; Savër, Plow, Rrapëz, Cermë, Gradishte, Grabjan, Gjaze.

In these camps, the family reunification took place with the sisters and the separated part, who had been sent to the Brick Factory in Valias, Tirana.

Tears of Tepelena

A few days ago I gave an interview to an Albanian journalist in the USA. I got to know him about life in the internment camps. The journalist had no information about life in these internment camps. She asked me an interesting question, which I had never been asked before. One of the questions was: These girls and women who went to work in canals, demolition, etc. – Did they cry, because the work – as you said – was heavy?

I was a little surprised by the question and immediately answered: In the extermination camp of Tepelena, the barracks were filled with the cries of mothers when the child asked for bread and she had nothing to give except her tears, and this was not her fault.

The barracks were filled with the tears of the mothers when they were leading the child to the life after the lack of food and hygiene. When they left for work, they didn’t cry. No, they did not give that satisfaction to those who had forced them to do such hard work.

No, they have never cried, but they have faced with great dignity that heavy work that the dictatorship imposed on them, and we cried in our souls, but never in our eyes. My answer impressed him a lot. Those in our memory are statues like heroines. Memorie.al