By Dom Zef Simoni

Part One

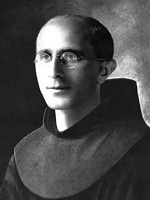

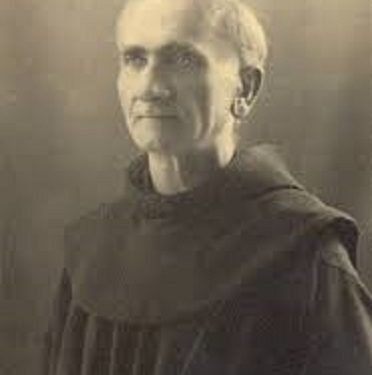

Memorie.al /publishes an unknown study by Dom Zef Simoni, titled “The Persecution of the Catholic Church in Albania from 1944 to 1990”, where the Catholic cleric, originally from the city of Shkodra, who suffered for years in the prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime and was consecrated Bishop by the head of the Holy See, Pope John Paul II, on April 25, 1993 – after describing a brief history of the Catholic Clergy in Albania – focuses extensively on the persecution suffered by the Catholic Church under the communist regime, from 1944 to 1990. The full study of Dom Zef Simoni, starting from the communist government of Tirana’s attempts immediately after the end of the War to separate the Catholic Church from the Vatican, first by preventing the Apostolic Delegate, Monsignor Leone G.B. Nigris, from returning to Albania after his visit to the Pope in the Vatican in 1945, and then with the pressures and threats against Monsignor Frano Gjini, Gaspër Thaçi, and Vinçens Prenushti, who sharply opposed Enver Hoxha’s “offer” and were consequently executed by him, as well as the tragic fate of many other clerics who were arrested, tortured, and sentenced to imprisonment, such as: Dom Ndoc Nikaj, Dom Mikel Koliqi, Father Mark Harapi, Father Agustin Ashiku, Father Marjan Prela, Father1 Rrok Gurashi, Dom Jak Zekaj, Dom Nikollë Lasku, Dom Rrok Frisku, Dom Ndue Soku, Dom Vlash Muçaj, Dom Pal Gjini, Fra Zef Pllumi, Dom Zef Shtufi, Dom Prenkë Qefalija, Dom Nikoll Shelqeti, Dom Ndré Lufi, Dom Mark Bicaj, Dom Ndoc Sahatçija, Dom Ejëll Deda, Father Karlo Serreqi, Dom Tomë Laca, Dom Loro Nodaj, Dom Pashko Muzhani, etc.

From the Autobiographical Book: Events on Earth

Foreword

I needed and desired to write this book, waking up the argument for many events that have happened within and around me.

Anyone can write something about their life, especially when they have reached seventy years of age, as I have. Since the philosophy of life resides in man, who can give us even more important revelations than those of the sciences that deal with laws and the cosmos, or something more valuable than a preserved museum building guarded by paid sentinels, we affirm that man is the realization of his own self, his own person. We are therefore obliged to embark on life, and since this life is God’s property and ours, to achieve our self-realization in time and space, until the end. But life does not end. This is an everyday and moment-to-moment connection of all our conscious and unconscious actions, which begins in time, and that is the day of birth, which in reality never ends. We are individuals, personal and social beings, who pass into eternity.

Contemplating my life, I see it filled with quantitative events and moments, for these reasons: firstly, like every human, I am a child of God, and secondly, I am the son of my parents. Poverty has befallen my life to the point of being the public pauper of the city. And don’t be surprised by these words: I have seen the good in poverty. Poverty, being states of suffering, makes you discover yourself, control your strengths, be unable to hide anything, and this can either build dignity in you or completely destroy your person. Without starting to embark on life, I and all of us have seen the gates of hell, and then, mature and thrown, hell itself terrestrially realized in communism. I achieved an ideal of becoming a priest. Having received a Christian education and, as a young man at the beginning, a gradual Christian culture, I had a strong desire to have Christianity as a rule of life, and later as an ideal. And the ideal in those conditions of the time, of a completely anti-human rule and with calamity after calamity, brought forth a vocation in my person. People emerge victorious in every circumstance, even with other good ideals. But I have emerged victorious; I have triumphed with a vocation.

God wanted me to be a priest of Christ and His Church. And furthermore, consecrated as a Bishop by the Holy Father Pope John Paul II in Shkodra, thus belonging to the Holy Catholic Church by desire and will, with reason and faith. This is an autobiographical novel. Autobiographical novels have a peculiarity in that they sometimes relate little to the world, but more to your own world. They are subjective, and then everything is enclosed within, in a deep horizon, with more mysteries. But since this novel is historical, it is precisely the history of a nation that was treacherously plunged into dictatorship. It is not only the persecution of the Church, which I mentioned in my book: Lights in the Darkness, but the persecution of the Church with analysis, with explanations, and the dictatorship, that infamous, terrible period for an entire people in bondage. We were all beaten, great and small, strong and weak, the good and the bad, the sacrificed and the dictator himself. Albania had completely fallen into fire. I intended to write this work with a great idea: that of Providence. This also saves an autobiography from any boredom and places the work in the reality of history and its values.

Until the Churches in Albania were closed, I often thought, as the Church says, that the life of man is with suffering and trial. But I, in truth, saw little in my person: some small and normal sufferings. These began later for me. Thus, with family sufferings, with the tragic death by drowning of my brother, with the salvations of priests and people, especially for faith, of Catholics, with the extraordinary scruples that tortured my soul and body for more than three years, with my arrest and imprisonment – twelve years, day by day – with being arrested two other times, but without being convicted, with serious illnesses and risk of death, and today, so many other small and large trials, even with some public slander in my priestly life that I have encountered, but which were short-lived. All of these have brought me, I say, a kind of spiritual joy, and I have seen that God has allowed them for the good of my soul. Thus, life and history everywhere came out to me as the work of Providence. On the one hand, He brought me the trial, and on the other, He gave me help, clearly seeing His plan.

A plan of goodness and love. And since Christ is God, no one can be placed above Christ. Since this novel is autobiographical, the main character is me. But a large number of very positive people also emerge, such as my family members, teachers, school professors, people of the Church, benefactors during the time of my imprisonment and my brother Gjergji’s, and in the time of freedom, the Church, the institutes of monks and nuns, everywhere, when I was abroad, in many European countries, the doctors, nurses during my illnesses in the hospitals of Shkodra, Tirana, San Giovanni Rotondo, the Heart of Christ in Negrar, and Verona.

I do not write about people who have done evil, except for some who have left a great mark. I pray for them, and for the living, I leave a path of repentance. I have tried to tell the truth purely and with sincerity, pointing out my shortcomings, faults, and at the same time, more of my nature, and with a desire to confess them before God and the world. Remembering this time that is left to me, I wish to gather myself even more into my memories, asking for forgiveness from everyone for my shortcomings, forgiving and praying to God for those who have done me wrong, praying to God and thanking those who have done me good. And I will try to continue my sacred duty, until I can no longer, until all the strength of life leaves me. I wish everyone a good reading!

The Author

The Godfather (Kumbar)

(The Year 1944)

Our city in this autumn brought dust from cars, trucks, and new noises. The German army, which was fleeing, withdrawn from the deep Eastern Front, also appeared in our city. The mysterious and invincible army was near us. A tired, but contained army. It was returning from the front, broken, heavily hit by unforeseen defeats. “We’re hurrying, godfather,” Anastas told my father one day. We also called him godfather as a sign of affection. The friendship of our houses had always been preserved. “I know, godfather,” he continued to tell my father, “that you Catholics don’t like this idea of the partisans entering Albania.” The godfather said it without malice; he was a good, simple, kind-hearted man to us, and he himself did something for the Movement. His nephew, Branko Kadia, who died in the war, and one of his apprentices worked hard.

“Germany will leave, and Albania will be liberated, and the poor, as the saying goes, will eat with gold spoons,” the godfather used to tell him. He said these words because we are used to giving opinions that we base on interested sympathies. Our country, always subject to occupations and political currents that have won over regions, zones, and layers, has waited for the winds to blow where they come from. Communism is entering the life of Slavism. As an Orthodox, the godfather linked salvation with the Slavs. “The day and hour have come for Albania to be saved once and for all,” the poor godfather thought. “The race of the East, which is our border, will do this,” he said. “We have the land divided, but the air is brotherly.”

The godfather always directed his head and eyes upwards in this approaching year, with all these great fantastic gifts.

And the sky, which has faith, has the same sun and moon. The stars that move have laws of justice, and the clouds that wander empty everywhere with rain, and are often useful when they have no passions and cruelty. The gentle godfather linked life with the holy Orthodox church. And many Orthodox people in Shkodra were with Serbia and Montenegro. He knew that the devil had worked in Russia, but Yugoslav land would not break the holiness. “Just a little more, and we will be fine, we will be happy,” the godfather would say. “The spoon is near the mouth. Let’s hit our teeth,” said another worker of the godfather, who was neutral, with slight irony. “My dear godfather, these things are nothing,” my father spoke to him with calmness and seriousness. My father knew the haberdashery stall well, where he had worked near Durrës with the merchants of Shkodra.

Later, when the dark events of Albania would happen, my father’s words would be remembered, because our godfather would complain bitterly and die without being able to eat properly, or even wish for the raki he slightly favored. The godfather’s sky began to fall on Albania. Life was mixed up. One Sunday, and this was every Sunday, organized armies watched mass at the Franciscan Church. At 9:00, it was the mass for them. They stood with the rigor of their faith and nature. We children sang in the choir. A violinist and a clarinetist also came. Both Albanians. We sang Handel’s songs at mass. A German singer who had joined the choir with us sang Schubert’s “Ave Maria” very beautifully. He sang “Down with the German army” and, with powerful voices, sang popular religious songs.

The Franciscan Fathers had sympathy for the Germans. The Fathers did not talk about the Germans. They only told us that they were a gentle and strict nation. “They will not stay here, they will leave.” The army had entered the Monastery courtyard. They never came into the schoolyard. The Fathers told us: “Do not mix with them.” In the city, the Germans had entered everywhere in the neighborhoods. They also came to our little street. They slept and ate meagerly in cars. Among the people, among the families, they were calm and gentle. They had hatred. They loathed the communists. They spoke words against them: “The communists are bad.” But I thought the communists were few, very few in number. There were many students in class. I didn’t like some. One or two of them stopped coming to school. What had happened? They had been caught. They had been taken to the German command.

They were sent to Prishtina, with a strict order, along with many others. One of the students never returned. He had been executed.

It was Zefi, tall and with eyes that sparked when he got angry. “My son, my son,” his mother would say, wringing her hands, “what has befallen us! Why did you need these things? Politics has taken the heads of so many people; let alone you, before your body has fully grown. And with the Germans!” Many women went to visit, and those who were close said: “What a black calamity this is for our Zefi. Who expected this? We were thinking he was going to be released!” Maria, Tonja, Lajdja e Filipit, Dani, and many others went. They cried loudly. Some more distant women talked amongst themselves. And one said: “And for what idea to die! This is called going to the grapes like a dog.” “But think, women,” said a hidden partisan who appeared unexpectedly, “he died, but he had a purpose. Some are fighting to bring bright days.” And she didn’t speak anymore.

The astonished city grew heavy, showing signs of turmoil and fear. People were being killed. Assassinations were being carried out. Blood in the streets. The communists were doing it. They also had their dead. They were put out in front of the Prefecture to be seen. They were torn clothing: full of mud and blood. People in groups were looking and leaving. “We will take revenge,” some voice was heard. The situation became very bad. Anxiety, insecurity. I went to see too. “They are communists,” they said. I felt sorry for them as human beings. “Why should they die?” I thought to myself. Among many people, a gaunt face, with an ominous look, whispered these words: “They died for Albania, to help the poor, to eat equally, they died for freedom.” For the first time, I felt something else for them. Since it was a cloudy day, I waited for the sun to come out and for the night to arrive, with a beautiful moon and stars.

Vangjeli i mirë (Good Vangjeli), whose house rooms were attached to ours, worried me one day. He worked at home and hammered shoes even for the partisans who were in the mountains. I never went into his room, but I would see him hammering shoes by the window of the room we had to pass by. On this day, he spoke to me about a young, grown man. He told me that he was very capable, and he, with the people, would liberate Albania. “His name is Enver and he has attended a great school in France.” With certainty and satisfaction, he told me that Enver would turn Albania into a garden of flowers. It was the first time I heard someone talking about Enver Hoxha. After staying a little longer, I quickly left Vangjeli’s window that day. Who this young and very capable man would be, all of Albania and its thorny gardens would find out in forty-five years. One day, the Germans left the city. They left the barracks, the hospital they had claimed as their own. A quick and rigorous departure. It was good that they left. This was one part.

November 29, 1944

The next day, the partisans entered. And this?! The day of November 29 passed in quiet, in a silence, in a day as if dormant! A cloudy day, without sun. Hour by hour, a fine rain started to fall, creating mud in the streets. No matter. We humans are also created from mud. These are only Albanians. We wanted to be only us. I saw the partisans. They were coming from the mountain, from the nearby hills of the city. They were not well dressed: some of them had old wooden sandals on their feet, dirty and unwashed. They had hats with a star on their heads. Stars in the sky, stars also on the hats. There were also some female partisans, dressed as soldiers. The women who saw them would say: “We haven’t seen anything like this. Girls in the mountain too. And girls dressed as soldiers?! Why do they need this, cursed be them, to get involved in these things?!” said a Lizë to Antonieta.

Some of them were communists. “They won?! The communists won?! But they are few, very few in number,” I thought. Some people who were around at the head of the “New Shops” and “Fushë Qelë” had come out to meet them. Anastasi was not there. Teofiku, Avnia, Ibrahimi, a Todo, a Kosto, who shook their hands. Even some women with veils. Many people gathered. I recognized all kinds of faces, but I didn’t know their names. There were some who hugged them, kissed them. There were some who shouted loudly: “Welcome to free Albania. Congratulations.” Some had even come out with bouquets of flowers. Where had they kept those flowers, towards the end of autumn?! Those beloved flowers that remain are needed for the cemeteries.

And then there were more people. How many more would come out later?! “Congratulations,” they told them, “today is the day of liberation.” And they walked with pride and, their voices getting entangled, they sang: “The flag of liberation is rising.” But is this liberation not the beginning of a great era, for years and for decades that would set in motion every person who would live in this time of masks and in this land of horrors?! It was the turn of the man whose horns could be seen. And what didn’t this man say, what didn’t he do?! The first night of liberation fell, it darkened. The day was awaited. The day and the days passed without a single light being seen again. Eclipse upon eclipse. Is this perhaps the day when man is neither in heaven nor on earth?!

A Kind of Work!

My father tried hard not to leave us without food. What complicated things for us were that our whole life took place in one room? The fire, the bread, the sleeping, everything cramped. Two small windows, without bars. Better without bars. Prison has those. Order was missing, although my careful mother and growing sister tried to keep it clean. We had no comfort. We couldn’t escape the destitution that had covered us. We had to be careful not to lose heart, because discouragement makes you lose the future as well. It enters secretly, at first without realizing it, and when some time passes, you can see the true decline. But this discouragement was not visible. I thought that the best way to be saved is struggle.

And this, in this case, meant resistance. This would be demonstrated in me through some attempts. Since I liked school, I did some preparation during the summer to move from the third year of the gymnasium to the fifth grade. But I got tired. The fifth grade was difficult back then. After the fifth grade, since life became harder and my father couldn’t find work, I started a job during the summer. I thought of preparing appetizers at home to sell them as a street vendor in the many taverns around the city. My father was decisively against this, and my mother opposed me with tears in her eyes, as it was something that our mentality couldn’t endure either. I had some difficulty at first. Everyone found out – relatives, friends, and the chosen families of the city, the professors – and with this, I was called the visible pauper of the city.

In the first tavern I entered, with the permission of the owner named Zef Kushi, people didn’t know me, but they were surprised to see me well-dressed. I made an impression. Within a few days, everyone knew me. Many of the tavern owners would put aside their appetizers to let me sell mine. “He’s a student. He continues school,” people would say to one another. Everyone eagerly bought the livers, entrails (kukurec), and meatballs, to help me. Everyone had respect, sympathy, and a compassionate pity. I did this work in the evenings, as soon as it got dark, and the work went on until late. After a few months, my brother, Gjergji, also wanted to come. Gjergji also took a container with various appetizers. Being five years younger than me, he did the work slowly. But Gjergji also delayed himself. He enjoyed listening to various conversations. He had a very curious nature. I loved him dearly and felt sorry for him, especially in the winter, because he was cold. Even my father, who stayed in one place at the “New Shops” to supply both of us, told me that Gjergji was delaying.

“Leave Gjergji’s work to me,” I would tell him, because I didn’t want him to yell at him. I knew why he was delaying. We would meet each other on the road, and sometimes even in a shop. “There,” Gjergji would tell me, “they are talking about the government. They say this government won’t last long.” Since he was little, he liked to listen to such conversations everywhere. “Don’t worry,” I would tell him, “we won’t continue this work either. We will help father as much as we can.” We continued selling in the heart of the city, starting at Zef’s bar, at the head of the “Rus” neighborhood, above the church, and in order to “Fusha e Çelës,” up to the municipality, a center where there were also selected drinking establishments, like that of Ndoc Koliqi and Zef Radovani, of Mëhillo, and then some others, which we could more easily call taverns, especially those towards Serreqi. We also had small taverns in corners, where some semi-drunk person would sing with a cracked voice.

My conversations with my brother were short, in the middle of the road, and then we would rush to finish our sales plan for that night.

When we saw that another seller, Bajrami, who was older than us, was inside a shop, we wouldn’t go in there. He did the same. Everyone bought from us, but we wanted him to sell too. When we were both close, about to enter the club, we would grab each other. He wanted us to go in. Bajrami had a good heart. Many people were drinking, and there was a great movement. It was a lively time. There were different categories of people: we started early with the sweating porters, the tired craftsmen, workers who had their preferred bars. Also officials, officers, intellectuals, and some professors of the state lyceum, who were rarely seen, mostly on special holidays.

Many people gave me courage. “Don’t be sad about anything,” they would tell me. “This temporary work is an honor for you.” The one who never spoke to me was Gjakova, the soul of Pjetër Bushati’s tavern: a small tavern, smelling of raki and cigarette smoke. “How does this world look to you?” Simoni i Tefës, this mixing gossip, who would put appetizers with both cheeks, would tease him. Gjakova, thoughtful with a black face, like a Gypsy’s, and who whenever he stood with his hands behind his back near the doorway, would say that “this world has the eyes and feet of the devil.” Gjakova had never worked in his life. He was a true slacker.

He drank and ate there without paying anything. He entered and left his shop ten times during the day and greeted and bid farewell to witty and gentle pleasure-seekers who drank at Pjetri’s, at his shop in Gjuhadol, and socialized with Gjakova. It was a good group of people, who would give you an egg without a yolk when they wanted to. It was my turn to listen for a while to this Shkodra humor, and to Gjakova, who spoke his words like a popular philosopher, and subtly and delicately jabbed at the new and unfortunate regime of the poor, which he called the regime of the ruffians. He couldn’t say this word aloud because he feared the regime, which wouldn’t honor him by being ridiculed.

Paulin Pali and Myzafër Pipa

And I moved from one bar to another. Two well-known lawyers of the city were also drinking: Paulin Pali and Myzafër Pipa. They were the city’s honor. About the former, Father Gjoni told me one day that he would come to teach law at the ‘Illiricum’ lyceum. But it didn’t happen. This good thing didn’t happen, because all the bad things would happen. The terrible trials began in the hall of the “Rozafat” cinema, against hundreds of so-called enemies. The enraged prosecutor Aranit Çela set the hall on fire and lunged like a savage beast against the many lives put in chains, a knife over their heads, bullets in their hearts and brains. Both lawyers bravely defended the rights, putting themselves in danger, as the same would happen to them – ending their lives in danger, these idealists amidst the tortures of the Security’s cells.

Both of them had heard that I was a student, and when I found myself at their table, as they were drinking outside since it was summer at Mëhillo’s club, they spoke to me kindly, a few words each. They ended their encouraging words with: “This way you will know life, even better.” I left them with joy, because these words were told to me by distinguished people, and the thought entered my mind: what is the knowledge of life and how is it possible? I thought that life was not something you held concretely, like something material, like a piece of land, like wealth, or like power. Until now, I had no revelation about this magnitude that cannot be grasped; it was like a darkness, and even darker in my gradually forming conscience.

I had formed vitality in my being. A vitality of struggle, but peaceful battles in one direction, because I think when people are young and walk in one direction, they always think of climbing upwards. Since I preferred to know ideas more, this kept me far from the true knowledge of life. As an optimistic nature, even amidst suffering, this clothed my reality with some fantasies. I call them fantasies, while these fantasies were thoughts.

Even on the starry nights, when I returned home late, taking turns on roads with few people, as most were inside their homes with faint lights, I, a little tired and not bored, had pleasure living in my subjective, internal, enclosed world.

I liked something spiritual. I identified life with the spirit. Was the knowledge of life beginning, perhaps? And I sat down the next day to write on the topic “Life.” I constructed some sentences. But I got stuck. Should I walk step by step to enter its mysterious building? I didn’t want to know if there are bad people, or people who suffer, or painful sights. I had my own for these. I didn’t have this out of egoism. I didn’t want this kind of reality, which I knew existed, but I only wanted the real thought. I wanted to see the good, the beautiful, and the ideal, and to fight for these. From one point of view, I was right. Why the bad, why the suffering, why the pain, whose origin I did not know. I was in a time and at an age when I needed clarity and direction, perhaps to avoid starting mistakes.

I preceded more with a natural goodness than with supernatural knowledge. I liked faith, and it grew and strengthened in me. Knowing people has been a secondary thing for me. Dealing with people seemed like a useless job to me. I thought, I cannot judge a person badly, he might be good. Or the opposite, when I judge him as good, he might be bad. Man is in motion. This judgment was a sphere that didn’t belong to me. I only looked at how people had ideas. The details of life that strongly belong to practice, which has its own unknown nuances, those were something else for me. Yes, when life started to take me with it, I saw late that the knowledge of people is also necessary. Then, to know life, one must also know people. And what must people know? One must know who surrounds you. One must know that there are bad-intentioned, egoists, arrogant, slanderers, thieves, liars, now in the new world, spies, plotters, violent people, exploiters, people who trip you up.

It is strange, perhaps the abnormality of man, that when he has a lot of work, he does everything. If he has little, sometimes he does nothing. I, giving myself to earning a living, which took my time, also prepared for lessons. In the sixth and seventh grades, I did well. The curiosities brought by the school and the events increased. I paid attention and saw something special. After the 29th, this fixed date of misery; it seemed to me that the school had taken on another appearance. The professors had a skill: an energetic lyceum. The subjects were beautiful.

Father Gjon’s philosophy hour was very engaging. A composition topic given by him: “Civilized peoples do not need leaders,” quite difficult for us, had its own meanings in this new time that brought forth horns every minute. I was seeing the time in detail. The older students stayed near Father Gjon in the schoolyard; they wanted to talk to him. One day, one of them asked him what these things that were happening were?! “Do not be surprised by anything,” the Father told them. “Whatever happens, the world will be surprised!” And this was said in those days of the elections of December 2, 1945. Memorie.al

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)