By Fatos Baxhaku

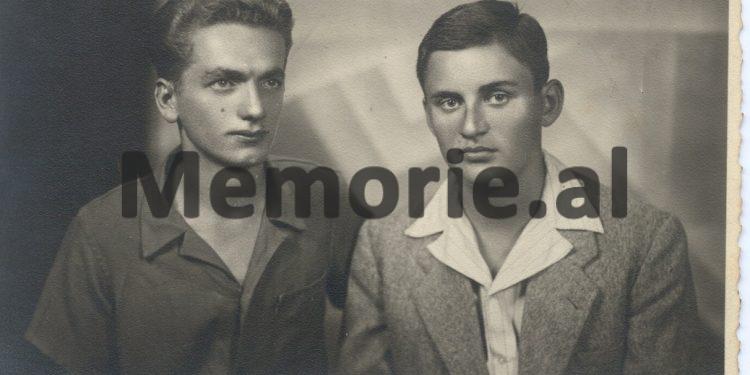

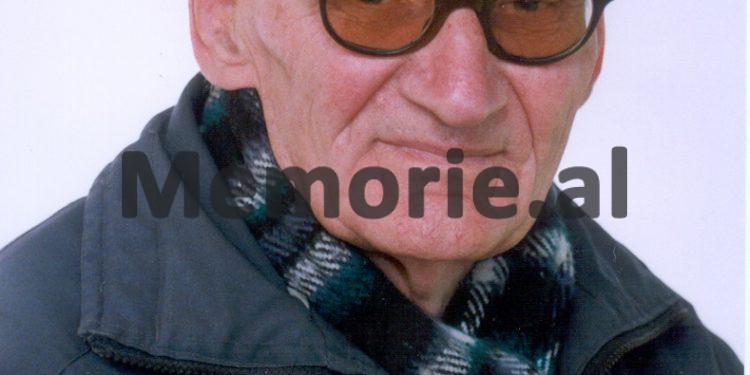

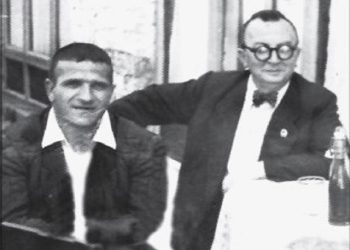

Memorie.al / At first we sit and stare at each other for a long time in semi-silence, at the edge of a table in the middle of a noisy bar, in the center of Durrës. On one side are we; eager to get to know and listen to a man who has survived the last circle of hell, Mauthausen. On the other side, there is him, tightly clutching a file. Who knows what Enver Plepi, the 74-year-old Durrës native, is thinking at this very moment. He must have surely said to himself, that expression that we have heard so many times: “Come on, come on, that’s how these journalists are; they finish their work and forget you quickly”. But after just a few minutes we have become good friends and Enver begins to tell, with a voice trembling with emotions and age, the most difficult story of his life.

Father’s closed shop!

In November 1943, Enver Plepi was a 15-year-old helping “father” in a fruit and vegetable shop. “I didn’t even think of a German, because I didn’t have a needle, at that time – says Enver – they stayed in their own places and didn’t mix with us”! But the peace in the small shop, in the old quarter of Durrës, would be broken very quickly.

The communists of Durrës and their guerrilla unit were among the most active in the whole country. From September to November 1943 alone, the guerrilla unit had killed nearly 25 people, among whom was the chairman of the National Assembly (the parliament of that time), Idhomene Kostur. Durrës itself was surrounded by several free zones, which were controlled by Myslym Peza’s partisans.

Albania’s largest port did not look so good, seen through the eyes of the Germans. Moreover, at that time, it was still unknown where the anti-Nazi allies would land. A possible landing on the Adriatic coast was not that impossible. The communists themselves did not yet know exactly who they were dealing with.

“Partisans came to the city, for one reason or another, and, although some of them were known, some of them also walked on the boulevard, or had meetings and conversations with their friends, often even on the street or in public places, among the communists of Durrës, there was a certain euphoria”, it would be written years later, in the official historiography. It was a euphoria that would be paid for very dearly.

The Germans decided to solve the problem, in their own way. The entire area, from Durrës to Kavajë, would be evacuated and transformed into an uninhabited military zone. The first raids were carried out in Kavajë, in early November 1943, but Albanian soldiers, who served alongside the Germans, saved many people in danger. The second time, on November 20, 1943, the Germans no longer had Albanian soldiers with them.

“Hafenfahrt” (port trip) was the name the Germans gave to the operation in which nearly 4,000 soldiers were mobilized. “I was returning from Kavajë, where I had gone to my people, when I came across a checkpoint, I didn’t think they would have anything to do with me and so I stayed. They put me in line with many others. I still didn’t know what fate was in store for me,” says Enver. The long ordeal of hundreds of people had begun. Many never returned.

“Rechts, links”

Enver Plepi doesn’t know German, but the first two words he heard pronounced in this language are deeply embedded in his mind. “They gathered us in a large square there in Shkozet, where the Plastics Factory was later built. After a couple of hours, they sent us to Tirana, in some large military trucks.

There must have been about 600 people from Durrës there. Most of them were old, only me and three or four others, we were young. In Tirana, they housed us in the New Prison, where Ward 313 is today. For about two days, the selection continued.

I remember an Albanian who helped the Germans in this work. He wore an overcoat and a large borsaline, his name was Osman Velja. He knew most of us personally. Then I heard for the first time in my life the commands: “Rechts, links”, (left, right).

From the first selection, 200 people remained and then there were about 100, who remained at the end. They told us that during these days, many people were gathered in front of the prison doors, awaiting our fate. In fact, by the morning of November 28, Independence Day, this gathering had turned into a silent demonstration.

Since then, whenever I happen to pass by the prison, I glance at that barred window of the prison. It seems to me that I experience once again, just as strongly, the fear and the feeling of insecurity that had gripped us at that time. Then they put us in the trucks. On this occasion, I learned another German word: “Komm” (come). With two German soldiers in front and four behind, the trucks took the “Elbasan Road”.

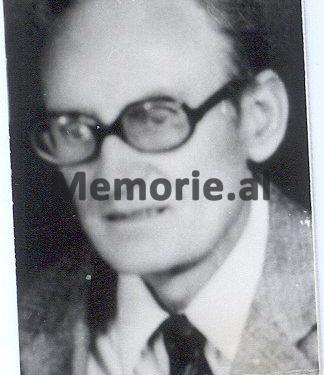

We spent a day in the prison of this city, and then arrived in Struga. I remember that we still had some money left in our pockets and they gave us permission to buy some pancakes, which we devoured within a few minutes. In Struga, I got to know Kozma Nushi, Telat Noga, Enver Velje, Vasil Misje, Leonidha Heba and others even better.

In the evening we arrived in Manastir, where they kept us for almost a month. They interrogated us for a long time and finally informed us that our final destination was internment. Where they would take us, we didn’t even think about it then”, recalls Enver Plepi.

The first encounter with death…!

“Until then, we had heard about the cruelty of treatment in Nazi prisons, but hearing about it is one thing and experiencing it and seeing it with our own eyes is another – Enver continues his story, now completely absorbed by the memories of that time – in July 1944, they brought us by train to Zemun, a large concentration camp in Serbia. There were nearly 5,000 internees there, from all over the Balkans, who were then sent to other camps.

Thousands of people slept in a three-story building, adjacent to each other. Here we began to smell the smell of death for the first time. It was very bad for food and water. It wasn’t long before a severe typhus epidemic broke out. Hundreds of prisoners died. Here we lost our first friends from Durrës. 18 people from Durrës could not cope with the disease. In Zemun, I was impressed by two people who I will never forget for as long as I live.

One of them was Mihal Konomi, from Vlora. He was a doctor and the Germans offered him better conditions if he agreed to be the official camp doctor. Vasili refused, he stayed with us, and helping us as much as he could, but he did not leave his friends. Another name stuck in my mind: Mihal Marko. He gave me a blanket. Now it may seem like a small thing, but at the time, it was almost like saving your life. Fortunately, both of them survived the camps and returned to their families.

It did not take long before we were again prepared for departure, by train. This time the destination was Banica, a suburb of Belgrade. Here, a four-story high school building had been transformed into a political prison. We, the Albanians, were housed in some light barracks in the prison yard. We realized that we would not stay here long. The greatest torture in Banac was hunger.

It was an incomparable suffering, which surpassed any kind of torture, but after a few days, a solution was found. By means of the finger alphabet, like the one used by deaf-mute people, we managed to connect with the prisoners who were in the cells opposite us. They were somewhat better than us, because once a week, food was brought to them by their families.

They began to bring food to their window sills. However, to get to their barred windows, it was very dangerous, because the guards would shoot without warning, anyone who crossed the barracks yard. I remember that this work was done by me, Mustafa Elezi, from Kavaja, and some other friend.

In the Heart of Hell

Enver Plepi has these dates firmly etched in his mind. He remembers exactly how the road to the hell of Mauthausen began. “It was September 15, 1944. They put us in several freight cars, all next to each other. Without food, without water, and without going out. We only got air from a few small windows upstairs. From them we learned whether it was night or day. The journey lasted five days.

We had no idea where we were going or what places we were passing through. The first time we landed in the middle of the journey was when Vasil Gjata, a former policeman for the Municipality of Durrës, died. We placed his body on the side of the railway and we never found out what happened to him! “In a sense, poor Vasili the desert became the first victim of the cursed Mauthausen,” recalls Enver, who seems to have spoken at some length, considering his age.

He wets his lips a little with a glass of water that is nearby and tries to gather some strength for the most difficult part of his story, while we, for a few moments, try to imagine how the internees from Durrës must have felt, perhaps instinctively feeling that they were getting closer and closer to death.

“On September 20, 1944, I heard its name for the first time: Mauthausen – Enver continues his testimony – we were in Austria, near Linz. They lined us up in front of its large gate and behind it I saw thousands of human figures moving around as if without meaning. Thousands of people dressed in striped clothes, were spinning in a completely naked landscape.

While we were waiting, a miserable figure approached me as if timidly. He addressed me in Italian. I told him that we came from “Durazzo”. He shook his head sadly and pointed to the camp gate: ‘You see that gate that is the entrance gate. Until now there has been no exit gate. But you are young, you love God and you survive’. I will never forget the portrait of that man.

Then they stripped us naked and took all our clothes. Before we put on our white and blue uniforms, they took us to the showers. Later, much later, we found out that there were two types of showers: one was the one we took. The other led directly to death, the gas chambers. We survived, we were young.” Enver narrows his eyes once more, as he flips through some photos of the camp, in a brochure published by the camp survivors.

“The next day, the real hell began. They took us to work at dawn. From that moment on, there were no more names. We were just numbers. I had 100266. The whole job was to carry a stone, about 20-30 kilos on your back, from the quarry to the vicinity of the camp, day after day, in winter and in heat, in cold or in rain, the same thing that led to certain death.

Lined up in fours, under the command of those they called “kapos,” who were privileged prisoners, we had to climb the 183 steps of the cursed quarry’s ascent dozens of times a day. I remember Telat Noga, who tried to help a prisoner who collapsed on the ground. The bosses immediately ran towards him. It was forbidden to help another. Whoever was weak had to die. That was the rule. Our eyes began to get used to the dead. You saw them everywhere: in the quarry, on the camp streets, in the bathroom, everywhere.

I remember that one morning, when I woke up; I saw that my bedmate had given up the ghost. I never found out where he was from. We were so tired and malnourished that we didn’t even have the strength to speak. This is how our life continued, if you can call it life, until May 1945. Over 400 of us had come from Albania, now there were only a handful of us left. The others, Kozmai, Telat, Enver Velja, and many, many others, couldn’t cope. “If this story had continued for a few more days, we wouldn’t be here talking together now.”

The Intoxication of Freedom

“Who would have thought of that?”, Enver Plepi seems to ask himself, as he begins to tell the final phase of this story, which seems to come from the movies. “I remember hearing cheers in the camp. I was so exhausted that I could barely understand what was happening. I could only hear ‘Hitler kaput’. Then we went out, our legs giving way from excessive weakness, into the main courtyard.

Here we saw with tearful eyes a tank, on which two officers had mounted. We realized that it was an American tank, because it had ‘USA’ written on one of its wings. I wanted to rejoice and cheer for myself and my comrades, I wanted to scream with joy, but I had no strength. We were in a strange state.

We were as if drunk with freedom. Special treatment began for us, in several camps set up by the Allies. Little by little, we began to recover. In July 1945, I was able to return home. The Americans provided us with some special cards, with which we could travel and eat. We first went to Budapest, then to Belgrade, from there to Skopje and then home to Durrës.

When I arrived in Durrës, it seemed incredible. I didn’t recognize my mother anymore, nor did she recognize me. We had both changed so much from this difficult story. Along with me, 14 other survivors returned. Other friends, like Beqir Xhepa, returned from the Italian side. There had been 440 Albanians in Mauthausen, only 23 of us had survived. 19 of the survivors were from Durrës and Tirana. We were just lucky. Nothing else but him”.

It seems that Enver has decided to close his gripping story. He starts to leaf through some notes he has brought with him and a brochure, where the name of the terrible camp stands out right at the top. “Have you ever been to the camp before?” we ask him one last question. “Yes, I was in 1980 – he answers as if lost – I also saw the monument to Odhise Paskal. I even went to my bed. At first I felt a little bad, because many heavy memories came to my mind, but then I gathered my mind. I was no longer afraid of death. Now I was free”.

Not just horror

There are many ways to read such stories. One of them has to do with our human side, with the fear of death. It is precisely this side that makes us, in most cases, read such events, some of the worst that humanity has experienced in the bloody 20th century, with a certain kind curiosity for the victims and a sense of disgust for those who invented this inhuman crap.

In most cases, whenever historians, journalists and filmmakers have dealt with these events, the general public has been moved for a while, wiped away tears with the corner of a newly-made handkerchief and continued to deal with today’s increasingly chaotic affairs. When Hitler’s dictatorship fell, in May 1945, everyone scratched their heads in thought: “How is it possible that such a thing could happen right in the heart of Europe?”

Everyone blamed the madman Hitler alone; thinking that now that he was dead, there was no way the world could experience similar tragedies. However, before the wounds caused by Nazi madness had fully healed, dozens of other dictatorships were born, sometimes even more sadistic than Hitler, Eichmann and Himmler, taken together. The world had not noticed.

He had seen the Holocaust as a fatal mistake, as an occasion to organize a long ceremony and then continued with the usual routine. Dictators and evil minds, meanwhile, continued to make plans on how to finish off these “intellectual villains” who dared to think differently.

Franz Zireis, an SS colonel, was the commandant of the Mauthausen camp. Until the very end, when he breathed his last in 1945, wounded by the bullets of American soldiers, he was completely convinced that he had done nothing wrong in this world. He had only carried out orders, for the good of the Law and the Nation. In fact, Zireis was also a very orderly and good family man; he had no vices, unless he called it a mania for burning people in ovens or gassing them.

Just imagine how many such types are still walking around today, shouting loudly for the law and, behind its implementation, hiding gnashing of teeth, old and new resentments, hidden desires for violence, impositions of useless thoughts or ideologies and, especially, an insatiable desire for power. If the history of Enver Plepi and the other martyrs of Mauthausen were read while remembering and guarding against such types, then their sacrifice would not be just an object of curiosity. Memorie.al