By Njazi Xh. Nelaj

Part Seven

Memorie.al / Impressions and memories from the life of the talented aviator, Colonel Niko Selman Hoxha, who fell in the line of duty on November 20, 1965, at the military airfield of Rinas, during a combat exercise with the MIG-17 F jet, in front of the regiment’s personnel and some military academic cadres. The impressions and memories have been gathered by Niazi Xhevit Nelaj in June – July 2012, in Vlorë, Tirana, Voskopojë, etc., during meetings with people and phone conversations, even reaching faraway Boston. Every meeting and conversation with contemporaries of Niko Hoxha and his relatives has been reflected in this material with fidelity and authenticity. The monograph reflects only a part of the hero’s life, that part which is related to aviation and flying, and does not delve into other spheres of the multifaceted life of the man who propelled military and air discipline and training. Niko Selman Hoxha, as someone who was orderly, disciplined, and very correct in the regiment, was also distinguished for his exemplary regime in life. He did not live in the barracks and did not eat in the quality mess of pilots but, due to the dedication and good management of the situation by his wife, Jolanda, nothing was lacking in his regime. This writing does not include Niko’s family life, nor does it touch upon his care for his sons, Valerin and Sashën, whom he left still young but surrounded with great parental care and love while he was alive. Other writings to follow will certainly shed light on those aspects of Niko Hoxha’s life, which have somewhat remained in the shadows in this monograph.

Author

Continues from the previous issue

Who was Niko Selman Hoxha?

As contemporaries of the commander assert, the pilots who remained in the regiment, when their colleagues returned from perfection, found themselves at a higher level than they did. Even in this matter, the colonel’s merit was undeniable. Without the initiative and determination of the colonel, perhaps the first aviation school in our country for the preparation of pilots would not have opened in 1958, nor would it have reopened after the bitter events of 1960, just as it would not have reopened after the interruption of friendly relations between our country and the Soviet Union in 1963, when many trainees who had interrupted the aviation program in the Soviet Union returned to their homeland. The initiative, courage, and dedication of Commander Niko Hoxha were present and decisive in every case. The portrait of the colonel encompassed these rare but essential qualities for an aviation leader like him.

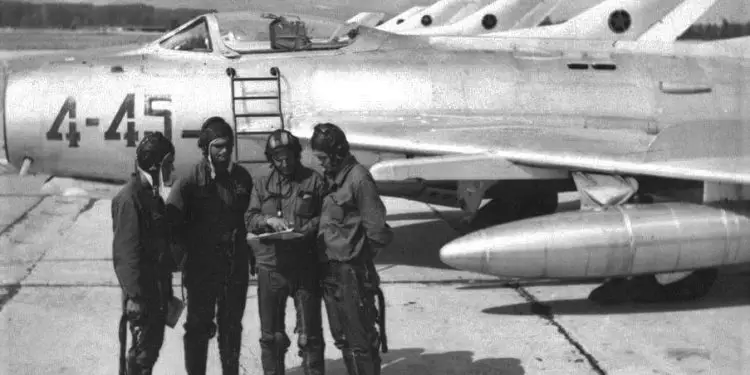

“In the spring of 1962, the fighter-bomber regiment was formed at the Rinas airfield. A squadron of 12 MIG-17 F aircraft was added to the MIG-19 PM fighter aircraft. Niko Hoxha, already proven for his organizational skills and equipped with valuable experience, was appointed Commander of this regiment, positioned near and in defense of the capital. Colonel Niko Selman Hoxha organized and led this regiment as he knew how and with the love he had for flying and the passion to aim for higher peaks, elevating the glory of his beloved weapon until he sealed his efforts, to catch the best, with his life at the age of 39, on Saturday, November 20, 1965, around 10:00 AM.

In Place of a Prologue

Niko Selman Hoxha came into life as a “destiny” for Albanian aviation. The colonel served in the aviation force at a difficult time filled with challenges and restrictions. Thanks to his rare individual qualities, with which Commander Niko was molded, he challenged the difficulties of growth and emerged victorious over them. The colonel became a legend; his deeds would be told from generation to generation and would be a source of inspiration for those to come. The long time that has passed may have influenced to obscure the event, but it certainly does not justify the protagonist’s forgetting.

Niko Hoxha will remain unforgettable, as even if some people remain silent, his life will speak for itself. Currently, Niko’s contemporaries are elderly, and for some, health issues have become theirs, but amidst clarity, they must remember themselves or awaken others to show the values of the colonel. Some lament that they have found themselves in positions from where they could not observe all the brilliance of Commander Niko, or others find it difficult to write and affirm, due to party reasons. I doubt there are people who do not want to write, fearing they may be judged for digging into the past.

Let them gather some courage and consider that the value of the past increases with the passage of years. Engaging with those who have made history and have become legends is something more than patriotism. My logic does not accept that there may be those who calculate material benefits from this work. I do not wish to judge people. A wise saying reminds us that “the knowledgeable know where the roof leaks.” Perhaps it is best to leave it to the judgment of everyone’s conscience. Some may not know how to write, while another may be caught up in health issues, etc.

Without attempting to provide guidance, I could tell those who know and wish to testify about the colonel to take advantage of moments of clarity and put on paper as they know things. It does not matter whether the language is fluent or not; what matters is the fact, the event, stated with truthfulness, not with doubts and obscurities. When I started writing these lines, it did not occur to me to make news or touch people’s feelings but to unveil the values of a man who came and became the fate of Albanian aviation. Therefore, I want to remember what cannot be forgotten.”

“May those who read this writing forgive me for the glorification of any fact or for the passion that permeates the lines, but they should believe that I have my reasons. Like all those who have worked and lived close to the colonel, for me as well, Niko Hoxha was an idol, an inexhaustible source of inspiration, and an example to follow. Therefore, I say openly that these lines were not written with a pen, but with my heart. In order to provide the readers with as many facts and evidence of the colonel’s traits as possible, I met and spoke with more than 35 people of various ages, profiles, and levels in Vlorë, Tirana, Voskopojë, as well as through phone conversations across the ocean. I did well to gather their valuable thoughts. I learned things I didn’t know.

Generally, a common denominator among everyone I spoke with is the same: Niko Hoxha was brave, courageous, a rigorous and persistent talented organizer, an initiator and forward-looking, cultured, strict, but extremely humane. If you try to summarize these traits, you will conclude what the blind pilot, Guri Merkaj, told me in Vlorë: “Niko Hoxha was a real man.”

The sayings of the people reinforced my belief that Niko Hoxha was and remains a multidimensional hero who cannot be forgotten. How well did Niko Hoxha’s contemporary, aviation veteran, Haki Jupasi, put it: “As time goes by, the memory and love for that man increases. Time forgets people, but Nikon is remembered not only by those who worked and lived with him, but by all the subsequent generations of aviation, as he left impressions, and those are transmitted from generation to generation.”

The veteran from Fterra, Skënder Sherif Dusha, who has worked his whole life alongside the Colonel expressed: “He was manly, which is why the cadres and soldiers would even give their lives for him! What we did not expect happened; the colonel touched the ground with the babishkë (a duralumin knife that is placed at the end of the aircraft’s fuselage, to avoid damage during the pilot’s heavy landings). After what happened, my head hurt for a month straight. That ‘boom’ sound at the ledhi (the edge) at the end of the airfield continuously echoed in my ears.”

The retired pilot, Gezdar Riza Veipi, one of the colonel’s devoted pilots, remembers Commander Niko Hoxha this way: “People who worked with Nikon elevated him, but he elevated himself, first and foremost. We received the first class of pilots, thanks to the determination of Niko Hoxha.” A soldier from that period, Pajtim Elmazi, spoke about the colonel like he was his father. Pajtim, among other things, recalls: “Commander Niko Hoxha was born that way. As a military man, he was decisive. He loved the aviation force with all his heart and was completely passionate about it. The colonel was never satisfied with the successes he achieved in his work.”

“He worked day and night to prevent even the smallest defect in the equipment, and he was tireless in his work. Niko Hoxha was entirely dedicated to the regiment, to the soldier, to the officer, to the civilian worker, and to the technology. There, he had his mind, heart, and soul. I remember with unforgettable respect this brave and legendary commander of our Army, and especially of the Albanian Air Force.” Çobo Skënderi, another first-class pilot, while telling me about the colonel’s deeds, emphasized with a literary and fluent language: “Commander Niko Hoxha was the only regiment commander who brought for the first class two groups of pilots, one in the ‘Stalin City’ regiment and the other at Rinas.

After him, no one remembered or took the initiative to advance the qualification of pilots for the first class. Niko Hoxha held the high title of: ‘Military Pilot of the First Class’. It was a time when we were ‘suffering’ for brake handles. To get out of the situation, we took action and gathered old, used brake handles, which we retrieved from the places where we had hidden them, cleaned them up, and put them on the planes. The colonel himself took to the air. He accomplished the landing and braked afterward. When he exited the aircraft cabin, we, the technicians and specialists, rushed with our observation notebooks in hand to get his opinion on how he did with the braking after landing. He was pleased with our work and thanked us, Osmani tells. Niko Hoxha was courageous in flight and cared a lot for the people around him.”

By chance, I met Alfred, the son of Ahmet and Fidarie Banaj, with whom Niko Hoxha lived in Valias. When the colonel passed away, Fredi was 9 years old, but he remembered that special man well. To my question about how he remembers Commander Niko, Fredi, a taxi driver, responded quite freely: “Niko Hoxha was quite a man. In appearance, he resembled Stalin and was very serious and authoritative. One day, we school children were walking to Kamzë through the muddy roads. The commander saw us, stopped his ‘GAZ ’69, stopped us, and asked where we were going. To school, we answered in unison. – But why to Kamzë,” added the colonel?

We, as if it were our fault, replied: “But there is no school in Valias, Uncle Niko.” Then he said, in a commanding tone: “Don’t go to school anymore; we will build one in Valias.” He said it and it was done. Thus, the new school was built in Valias, and we students of that time saved about 40 minutes from traveling to get to school. He also acted similarly for the construction of the cinema in Valias. The voice of Niko Hoxha was heard, and he was competent,” concluded his memory, Fredi Bana.

The values of the colonel as commander and pilot were also emphasized by the aviation veteran, one of the leaders of the high aviation school, pilot Bahri Meshau, from Bubës of Përmet. Bahri, amidst the emotions conveyed by distant memories, recalls the colonel as follows: “Niko Hoxha was born to be a military man. As a commander, he valued you as you deserved. There is no commander who gathers soldiers in the afternoons and stays in their company as he did.”

“Bahriu has known the colonel since 1959, when he was a student pilot and the colonel commanded the squadrons that were producing new pilots. Many tales from Niko Hoxha’s work, as a pilot and as a leader of aviation, were shared with me by the elderly Sulo Gorica, who used supersonic MIG-19 PM aircraft for a long time; he was even a technician for the aircraft that the colonel liked to fly often.

Sulo Gorica’s opinion of Niko flows smoothly: “Niko Hoxha imposed respect. He had excessive confidence in the technician and the aircraft. I remember well when he flew the MIG-19 PM jet aircraft, without special training. Sometimes I intervened regarding the engine’s operation and other technical issues, but he didn’t like to be interfered with, as he wanted to be in control by himself, even in this regard!”

If I had the chance to meet more contemporaries of Niko Hoxha, I am sure their opinions would be similar, that the colonel was unique and incomparable. The giant named Niko Selman Hoxha came to aviation as a stroke of fortune for us; he worked, led, sacrificed, and devoted himself to elevating the aviation force. We wanted to have him among us longer; as the colonel had so much to give us and to teach us, but suddenly he left us, flying away like the wind, as if he had come from some other planet, on a courtesy visit.

Veteran Osman Bozhiqi spoke well: “The air accident that took Niko Hoxha’s life was a heavy blow to our aviation.” I share this opinion, along with the view of the blind pilot, Guri Merkaj, who, grieving, sighed and told me: “Ah Njazi, people like the colonel do not come again.” There is one detail that somewhat comforts us. Niko Selman Hoxha did not perish in bed, suffering from a long illness, but fell on the battlefield like a hero, in the line of duty, before our eyes. His death, in the line of duty, in the arena of men, brought us not only sorrow but also a valuable lesson.

As Beqir Balluku said on this occasion: “Niko was killed to show you that if you break the rules of discipline, you will be killed!” The Minister of Defense at that time likely had in mind the adherence to the technical parameters of flight, as a science, beyond which no one can step, regardless of their qualification level. I will return again to those who have not taken the effort to write about our hero, both as a passionate pilot and as a talented organizer. They should believe me that I hold no grudge against them nor harbor any resentment. After all, each person does as much as they can and what they know; outside of their nature, a person cannot step out!

Oh, that cursed Saturday!”

“The days of the week are all the same. They come one after the other, bringing possible changes. Sometimes for the better and rarely for the worse. However, the bad that that Saturday brought was of significant proportions and hurt us deeply. Some more, some less, we all felt this loss. That’s why I called it: ‘The accursed Saturday.’ Who does not remember that day, November 20, 1965, which, as it blackened and darkened with clouds heavy with rain, suddenly took away our dear friend and comrade, Niko Selman Hoxha, who became like the star that illuminates the world.

The colonel vanished, just as meteors fall and fade while shining. He departed this life as an eternal soldier of this land, extinguished a spark that ignited the great fire of progress in aviation, and a great heart, which should have continued to beat for the good of this country, ceased to beat.

Many eyes were filled with tears that day, and many hearts were wounded. It seemed as if the heavens opened up. The mothers and sisters of Laberia expressed their sorrow through wailing, the poets wove verses, and the people raised songs. The glory and honor that belonged to Niko Hoxha during his lifetime he also received in a dignified farewell, as he deserved as that man. Those who saw the bitter event, as I also witnessed, surely have that grim scene recorded in their memory, and I believe they reflect on it whenever they long for the commander.

A few words about the events of that day!

My heart does not want to write these lines and to bring back that shocking scene, but I have no choice; I must put my thoughts into this lengthy narrative. November 20, 1965, will be remembered and commented on for a long time in the environments of aviators and aviation enthusiasts. That year-end, several pilots from the Rinas regiment, for various reasons, had not fully completed the schedule of air strikes against the targets on the ground. Some had one, and others had two flights of this nature left to be carried out. Niko Hoxha had one flight pending in mountainous terrain.

The flights with gunfire that day were generally planned for the mountainous range of Kruja, which was located at an altitude of around 500 meters above sea level. To execute the firing in this polygon, according to regulations governing flights of this nature, the pilot needed to be at 1,000 meters above the surface of the target where he would shoot. That Saturday, the clouds’ lower layer was at an altitude of about 1,000 meters, which did not allow firing in the mountainous polygon of Kruja.

In previous days, the colonel had conducted a lecture with the officers of the Military Academy “Mehmet Shehu” in Tirana regarding the combat use of aviation and had promised the cadets that he would demonstrate in practice what he had explained in words. And when Niko Hoxha made a promise, he turned it into reality, with his personal example. To keep his word, since the clouds on that day did not allow firing in the mountainous polygon of Kruja, the commander of the regiment, Niko Hoxha, ordered his subordinates to prepare a field polygon in the reserve area of the Rinas airfield, at its southern end.

The planning of that day was redirected to firing in field conditions, at the improvised polygon. For this purpose, in the green meadow at the end of the runway, a circle was drawn with white chalk, with a radius of 20 meters. According to responsibility, those tasked set up security in the area with armed guards. To prevent the movement of people and living beings where the shooting would take place, with the aircraft, the colonel personally engaged in organizing the flights. He directed the cadets to position themselves on the edge that separated the airfield from the corn field, across the drainage canal, as the highest place from where the pilots’ maneuvers would be clearly visible during the shooting.”

“He took the car in the role of the driver, where the flight leader was seated, and positioned it near the anti-aircraft battery, which covered the airfield. He ordered the pilots of the four aircraft that would be performing the firing, which he would lead himself, to enter the cockpit, turn on the radio, and remain on standby to receive orders to take to the air. The flight leader at the airfield was Major Haki Jupasi, a first-class pilot, serving as the deputy commander of the regiment for flying.

The quartet of aircraft that would showcase the firing took to the air, heading south at 176 degrees. The takeoff was executed with pairs of MIG-17 F aircraft of Chinese production. After breaking away from the ground, in straight flight, the formation compacted, forming a square (four-ship formation) with reduced distance and intervals. The formation in the air was led by the regiment commander, Colonel Niko Hoxha, with the aircraft numbered 211, which was piloted by Hysen Domi from Maminas in the Durrës district. /Memorie.al

Continues in the next issue