By Adelina Gina

The sixth part

-“I cried for you like dead, I waited for you like alive”-

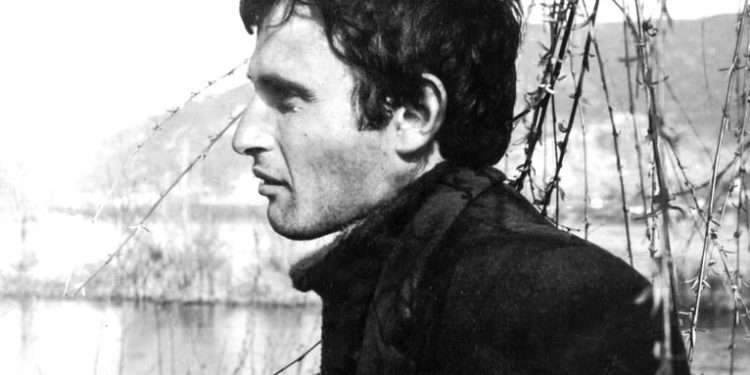

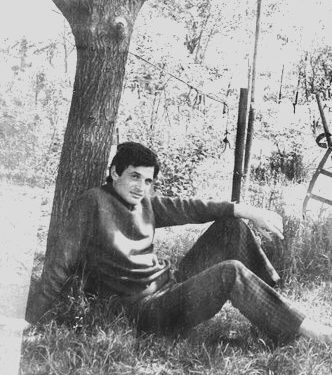

Memorie.al / Rescue Gina, graduated in Journalism at the University of Tirana, in 1974, playwright, screenwriter and librettist, in the early 70s, thanks to his extraordinary talent, his work, works and creativity , “shocked” the artistic institutions of Tirana, such as; The People’s Theatre, the Opera and Ballet Theatre, the High Institute of Arts and the Albanian Radio-Television. He was one of the most sought-after chiefs and senior leaders of these institutions. In the time period 1971-1974, he left his mark, having collaborated closely with some of the most famous names of that time, such as: Mihallaq Luarasi, Kujtim Spahivogli, Pirro Mani, Mario Ashiku, Zhani Ciko, Nikolla Zoraqi and director Mevlan Shanaj and operator Pali Kuke. But the traces he left in these cultural and artistic institutions were unfortunately lost in the official silence of the communist regime?! In August 1974, Shpëtim Gina, lost his life in unexplained circumstances, drowning in two feet of water, in the river Drojë of Mamurras, (where he was performing the military choir together with other students), two days before, he had put a lightning sheet to the Chief of the General Staff of the Army! Was it really an accidental death, or was Shpëtim Gina eliminated by the State Security?! Why his “friend” who was with him until the last moments, declares that; “The body that was taken in the ambulance, wasn’t it Rescue?! Or the doctor of the military department of students, Mark N., who says: “We immediately went to the scene, but we did not find the body of Spetimi”?! And his family, why insists that; “They didn’t allow us to open the coffin before the burial when they brought it home and years later, we opened the grave in ‘Stalin City’, to bring it to Tirana, where we had moved as a family, those bones were not of Salvation, as they were missing. ..”?! Many questions, which have not yet received an answer! His sister, Adelina Gina graduated in journalism in the late 60s, in a book of hers titled; ‘Where did you take Salvation’, published in the USA.

It was early, a cloudy morning, and those people who escorted us were as if frozen. It wasn’t until we got into the car that I breathed a sigh of relief. On the way back, I thought: “They are checking my movements. Mira and Petrit should be ordered, so they can be careful.” Not even two weeks had passed since this event, when Petriti told me that when he was coming back from school, two people were fighting on the boulevard, and I happened to be there too. An old man approached me and said: “Are you from Berat?” “Yes”, I said. “I understood when you spoke,” said the man and continued: “Whose are you?” I told him my father’s name. The man said: “That’s right! yes, I have him as a friend”. We walked a short distance and he asked me to meet in the afternoon. “This is a Security man, – I said, – what do you think?”.

“And I think so,” said Petriti, “that I didn’t even speak, while he said that he recognized me from where I am, from my speech”! I know, my brother hardly speaks, he is very silent, pay him as they say, he doesn’t say a word. “Did he tell you what his name is?”, I asked him. “Yes, his name was Pirro and he said he was a teacher and worked in a night school. There is a mark on his cheek,” continued Petriti. There was no doubt, this was a provocateur. This is how our friends were coming. The three of us talked about it. I ordered Titi to be careful. “Okay, go meet him, but walk alone in places with light and where there are people”.

At that time, on the “Street of Barricades”, there was a bar called “Liria”, full of smoke and people, an ordinary bar, where beer, brandy and chops with salad were served. His father’s friend, his brother, introduced him to this bar. As soon as they sat down, he handed her a pack of cigarettes. “I don’t drink it,” said Titi. Then he ordered two double shots of brandy and chops. Petriti, in contrast to Shpëtimi, who ate only pastries, who as a child had the desire to drink a little. And when he puts his lips to the glass, it looks like he’s not drinking, but not only is he drinking, but he’s holding the drink. After the double finished, the father’s friend, among other things, had asked Petriti about the death of Spetimi. How could he drown in so little water, he had provoked her. Petriti replied that his foot slipped and he fell. “Why was he so stupid?”, the provocateur continued.

“Yes, there have been many such cases”, said Petriti. When they were separated, he had ordered it, so that he would take care of me, because I bought a lot of cigarettes. I was waiting with frozen heart for his return. During that time, who knows how many times I cursed myself for letting him meet the provocateur. Petriti told in detail about the meeting. He had passed the test. We laughed with my father’s friend, the teacher, who offered Petrit, a sixteen-year-old, cigarettes and brandy. “It seems he doesn’t even know the psychology of the teacher,” I said. Later, when we got a house and father came to Tirana, the brother happened to meet “father’s friend”, the man with the sign, and invited him to the house.

He promised to come and disappeared. The father said that he had never known such a man! Petriti never met the man with the sign again. Always, when it’s said that it’s not good to drink, he says: “What if I didn’t drink twice that night, every time you get drunk, you have to learn not to get drunk, who knows how it goes.”

This was a strange death. A month after her and the father had made his own efforts. Through his people, he found the opportunity to go to the Attorney General’s house. He received him well and listened to his father’s complaint. The father told him the incident, as he had been told. It happened on August 15, around 12:30 p.m. At around one o’clock that day, he was taken out of the water, put on top of a canoe and left lying on the ground until nine o’clock in the evening, so that the coroner could come. This area belonged to Kruja. They could hardly find the doctor, that’s why they left him there for so many hours. Then he was taken to the civil hospital, where an autopsy was performed.

The father raised two issues. The carelessness of the Kruja investigator, because after two days, Mani brought pieces of soap, which the investigator should have done. By leaving it so long, at night, the investigator had nothing to see and that Dhori H., the only witness at the scene, was not questioned, but was given permission to go home for two weeks, because he was shocked. The prosecutor called the father’s complaints right, asked him in writing, and when the father submitted them to the office, he asked the father for permission to reopen the grave, to be examined again. The father agreed. A month passed no response.

The father went to the General Prosecutor’s Office. There they told him that the prosecutor had been transferred to Vlora and that the case had passed to the deputy prosecutor. He had drawn the attention of the Kruja investigator for negligence and told his father that the Kruja investigator refuses to reopen the grave. The case was closed. “Something must be done, said the father, to open the case. In my opinion, the prosecutor’s departure was “related to the incident”. So he addressed a complaint to the Kruja investigation, where he presented such a suspicion: “Maybe a murder happened with motives of love?! Dhori loved Anna before and now, out of jealousy, he strangled Shpeti”. Not much time passed after the complaint and we were called to the Kruja investigation.

We had just arrived when Ana got out of a red car. Father entered the investigator; I did not get out of the car. She came and sat with me in the car. Lit by a cigarette, I sat like on thorns, that maybe she would ask me and the conversation that she was being used to discover the event would be opened. You know that the father’s suspicion was just a pretext to open the process. Near the car, a neatly dressed boy passed by, she opened the car door and rushed towards him. He smiled at her. She ran away with him. He forgot his bag in the car. It was just me and Ramizi, the newspaper driver. I don’t know what prompted me, but I opened her bag and the most incredible thing happened: there I found a printed sheet, part of the plays of Salvation.

The character talked about a suicide and that he was bored with life. I froze. And where did he find this sheet?! Why does he need it with him?! That it was the writing of Salvation, there was no doubt, and it was understood because of its concise style. As I was putting the letter in my bag, my gaze met Ramiz’s. That’s all. He acted as if he didn’t notice anything, I don’t know what he thought, but he must have seen the expression on my face, that I was right. Ana came after a while and took the bag. “Who was that boy?” I did it. “The head of the investigation, I had a friend,” she said and left.

I was sitting in the car, waiting for my father. An hour passed. A young man, about twenty-five years old, looked worried. He casually approached the car, we looked into each other’s eyes and backed away. He also made a tour of that piece of land and entered the investigation building again. After three hours, the father came accompanied by two people. He crashed into the car, his lips were crushed. “Let’s go”! Said. On the way we both did not exchange a single word. At home he told the investigator what happened. “The whole time, they kept me with cigarettes, they welcomed me with respect. It was the chief investigator and a young investigator. I asked to read the incident in the file. It was the same story that Dhori couldn’t get out, he left and found a shepherd on the way, and his name did not even appear in the file.

Since the coroner was absent, they left him at the scene until nine in the evening. They took him to the civil hospital and performed an autopsy. “I put these matters to him, said the father. Why wasn’t the main witness asked, Dhori, he was allowed to go home on vacation, because he was too worried. Second, you went there at nine o’clock in the evening. What did you see? , that Mani brought us the pieces of soap, from the place of the event? At this time, the foreman told me: “Don’t worry, Mani, because we will throw away the irons. That we heard that he said up and down, that he saw lesions in Shpëtimi”. I protested, this is a lie. Mani came the next day, after the funeral, and there was no way he would say such things. The third thing I want to know, what the autopsy revealed”.

They called the coroner. He indicated that every organ was fine and that he had only drunk a little water. “Listen,” I told him, “according to the laws of physics, when the alveoli open, you either drink completely or you don’t drink at all.” “Well, there was some liquid, the doctor said, maybe it was food.” Question after question, he, the doctor, began to feel bad, so much so that he asked the investigator for permission to go outside, because his head was hurting. “Leave it; I told him, he’s more worried than me, his father”. When the doctor came out, the chief investigator told me: “He is responsible, if he didn’t do the autopsy well, we’ll throw the irons”! The doctor was that boy, who was anxiously wandering around the car!

“My opinion is this,” the father said they had thrown a white rower over him. You said he had blue knickers and a yellow rower. They tried to tell me that maybe he had epilepsy and fell into the water hole. I categorically denied that.

Then they moved on to the suicide option. “No, I told them, my son loved life, he had taken the drama with him, and he was not easily broken.” I didn’t tell Anna what I found in her bag and where she found the sheet, but she didn’t tell me anything either. We both passed the event in silence. After many efforts, we bought a house on “Rruga e Elbasani”, near “Student City”. Its windows fell from the forest, the voices of the birds could be heard, it was quiet. Finally the four of us were together.

Mira was preoccupied with lectures, she studied constantly and Titi prepared every day, while I had to fight in the newspaper, I had not been fired yet, but I felt that the moment was approaching. I wasn’t so sorry that they were removing me, but I couldn’t find the reason why they were removing me, how was it?! On one of those days, when there was a meeting of the editors and Sofua had said something, I turned to Mantho Bala, the deputy minister of culture, who was also the secretary of the party bureau of the dicastery, and wanting to know the truth of the departure, I asked for an open meeting of the party organization, where the newspaper would also participate.

Five minutes before the end of the official schedule, the meeting was announced, in which the Minister of Education himself participated. The minister, from the beginning of the meeting, began to treat me well. The editors were silent. Kozmai, the secretary of the collegium, threw the thesis that he was removing me, that the culture pages were cut in the newspaper and that I was covering this sector. Everyone’s face lit up.

They found the cause. “Okay, – I told them, – but I’m the same as the other colleagues from the newspaper, I’ve completed the same school. It’s very good that in addition to the problems of education, I also know art and culture.” Not the day they answer me. The meeting lasted. I understood, those who talked, who found arguments, were not taking me away. Someone else took me away. Why?! When the meeting was over, Peçi was sitting at the door, like a beaten dog. He was very worried. He had not been able to find out that such a meeting would take place, maybe they, his ustallars, who knows what they told him. He was an employee of the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

I made a plan. I decided to go up to the beast’s lair and try to direct it, according to my plan. This had to be done carefully. They are terrible. They don’t want to put you in a madhouse, there you really go mad and everything closes. I would act like them, without fuss, without words.

One morning I delivered a letter to the duty officer of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, on which I had written my name and home address. The text was this: “Comrade Minister, I want to talk to you about an issue that has worried my whole family. I won’t take you more than fifteen minutes.” And I went to the newspaper. It wasn’t eleven o’clock yet, when the minister’s secretary informed me that at twelve o’clock I should go to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, where my friend Farudin was waiting for me. Poçari, the secretary of the Minister of the Interior. The man who was waiting for me was of medium build, with gray hair and gray eyes. In a low and gentle voice, he showed me the chair. His voice and his humane demeanor surprised me.

Thinking about where they work and what they do, in my mind they were different. I was surprised. The building of the Ministry of Internal Affairs has two entrances, one from the boulevard, I don’t know who enters here, maybe it is formal, and the other from the side of the People’s Theatre. Once inside, there is a small counter. The dezhurn officer, to whom I also delivered the letter, explains. Ministry employees come and go there. On the right, was the room I entered? I sat on the chair; a table separated me from Farudini. Four bare walls, cold cement and no windows. Just like a dungeon.

I don’t know why I remembered this phrase “even walls have ears”. “What about you,” my father told me later, “how did you go? I don’t even turn my head when I pass there.” It was the terrible machine of the dictatorship. How many people had thrown from the windows! Good thing this room had no windows. “The minister himself would be waiting; he is busy with an urgent job, anything you have, told me.” “Yes, these are not the ones who are interested in people’s problems. What did he say?! The minister himself would be waiting for me”, I reasoned with myself. His voice was soft. Very well, now my game would begin. “I work in a newspaper and these days I was laid off, I have to leave the newspaper. The reason for the layoff doesn’t stand.”

“Why did you come to us,” he asked, “we don’t deal with these problems. You should go to the Party Committee.” “I came here because you ordered me to be removed. One of your employees (it was about the uncle, Beluli), was interested in knowing who I was”, and I told him the incident in the cafe, that morning when the meeting was held, and that like Sofua, he had said that heavy things are weighing on me. “These grave things, only you know.” “Isn’t your father mixed up with the oil people?”, he asked, then added: “On you and your family, nothing serious is ordered. You don’t know who Sofua is?! He has left the Party behind his back”!

Sofua was one of those from the Tirana Conference, which, surprisingly, had been rehabilitated. “Yes, you have a communist”! I interrupted him and continued: “I can’t run away from the newspaper now, but everyone thinks that there are serious things about me, which Sofua knows and which you told him. This is where these words came from.” I was making conditions, what would they do. The meeting ended, we shook hands and I left.

Maybe they expected something else because they moved quickly. I, who had formulated the letter in an intriguing way, did not expect to be called within three hours. On purpose, I had put my home address; they called me at work, so I was a known person. What did they think I was going to say?! Now how will the work be done?! Would they remove me from the newspaper?! I had all these questions in my head. Time would tell if everything was done.

After going to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, some time passed, there was no more talk about my departure. Kozmai, the college secretary, started to misbehave with me. When he divided the work, he didn’t give it to me to edit or write. The work got to the point that when his friends were on duty, he would lock the door. When I came to work, the office was closed, only his and the typist’s office were open. No matter what I did, I couldn’t run away, because maybe he was doing it as a provocation, so that tomorrow he would say, “this leaves the job”. So I used to go, stand by a window in the corridor, and spend October there, on foot.

Good thing the sun was shining there. With destroyed nerves, with all that pain, I had to deal with Kozma G. One day I ran out of patience and went and complained to the deputy minister, Mantho Bala. He called Kozmai into my presence. And you know how he answered? “Yes, it’s true that I don’t give her work, because I don’t have political faith in this, I don’t leave the newspaper in her hands.” The deputy minister shouted at him: “Either you will ask for his forgiveness, or I will take you there from Vunoi, where you came from.”

A formal meeting was held and he pretended to apologize. Sofa was suspended from work; all functions were performed by Kozmai. After six months, they called me to the staff office and told me that I would leave with a reduction, at the disposal of the education section, to be placed at work in one of the schools in Tirana.

I took the work book and entered Kozmai’s office, closed the door and said to him: “I’m leaving at last, here is my work book. This war you made me, you pay to your daughter, I don’t want you to tremble the body”. He muttered something, as if he was afraid, not of me, but of the curse, it seems his daughter was in pain. I opened the door and got out. I was not upset; I had forced them, from the Security, to keep me for some time. So they acted according to my plan. What should be done now? Memorie.al