second part

-A year after establishing diplomatic relations with Tirana, Bonn sends the first “researchers” to the “land of eagles”! –

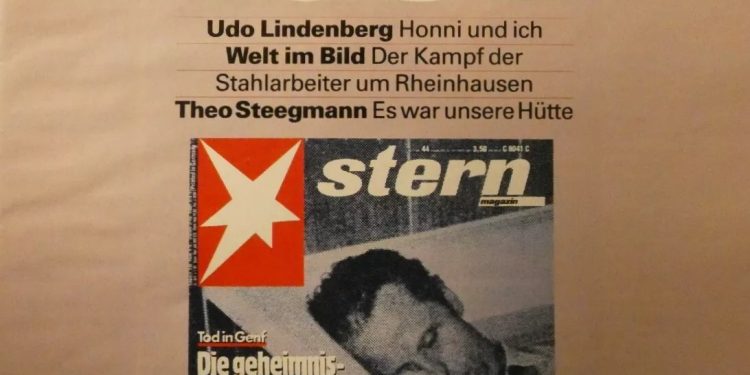

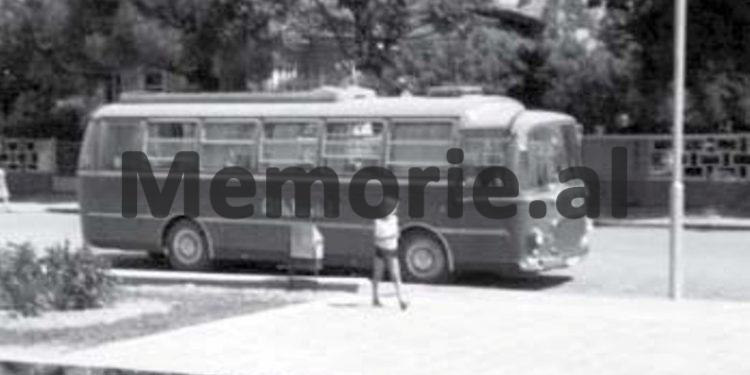

Memorie.al / A rare material prompted us to publish almost in its entirety the content of a report published in a special issue of the prestigious German (at the time “West German”) magazine “Stern” in 1987. A group of journalists, certainly accompanied by photographers, thus become witnesses to an atmosphere that is as hopeful as it is painful for the Albanian people in the final years of the existence of monism. Arriving as tourists and carried in “luxurious” buses (by the standards of Albanians at the time) equipped with air conditioning, they see a bitter reality, although they try to be as objective as possible and reflect what they actually saw, also giving us many positive aspects of what is now known throughout the world as “Albanian hospitality and generosity.”

Continued from the previous issue

The photographer from “Stern” (the German magazine), Cornelius Meffert and I, feel on our first trip to Shkodër like kindergarten children going to see colleagues from other kindergartens. There is always someone watching even the movements of our fingers.

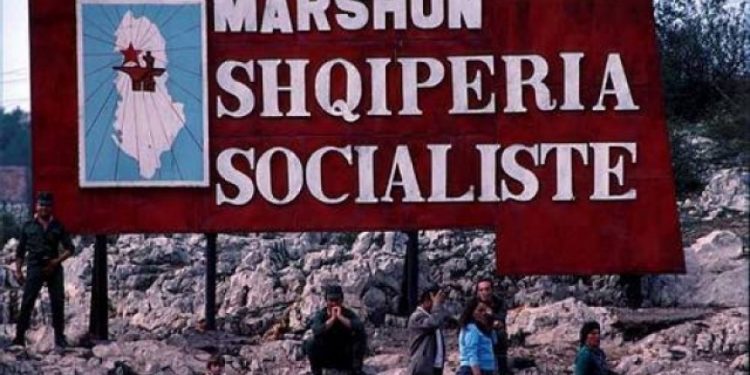

It’s nice; the monuments can be photographed without a problem, those of partisans, writers, and poets, as well as the heroes of the people and the inevitable Stalin. Also the slogans, large banners in reddish and black.

But the horse-drawn carts that pass on the boulevard with large milk containers, while the cart driver forcefully raises the whip high, make our photographer Meffert’s camera rise and quickly snap a photo.

Then some children put their hands in front of their faces and run away. But the eyes that watch us from the balconies and park benches accompany us the entire time.

“Mirdita,” I greet the maintenance workers who look at us with great curiosity. “Are you okay?” They smile at us. We exchange a cigarette. “Deutschland gut,” – they say to us. “Bekenbauer, Rumenige.” And Cornelius Meffert manages to snap his first photos freely, while we continue to smile and greet each other.

It’s Saturday night. At half past ten, the television plays the national anthem. End of the program. At 23:00, the hotel also closes. But given the fact that there are foreign guests, they have extended the time by one hour. Albania goes to bed early. The workers must rest.

But we cannot sleep. From the restaurant on “Stalin” boulevard, across from our hotel, rhythmic dance music, clarinets and saxophones are heard. 22 guests are dancing and singing together, following the rhythm. They are celebrating a wedding.

We go nearby and an elderly man gets up and accompanies us kindly and with a smile towards the hall. We have to celebrate with glasses full of raki and see mountains of cheese, prosciutto, and meat before our eyes.

The bride looks somewhat sad. She is leaving her parents’ house forever today. Meanwhile, the groom, drenched in sweat, welcomes us. The bride’s father accompanies us to the door, and his brother takes us in his arms. “We thank you for the honor you have given us,” he says.

Furthermore, what we are supposed to see is, as a rule, determined by “Albturist.” The state tourism agency has designed a program of visits that thus enables us to get a clear overview of what has been achieved in the People’s Socialist Republic.

We see children’s kindergartens with little ones reciting poems for the party (“We are the flowers of the party”). We then sit in a laboratory of a high school in Peshkopi and hear that before the Revolution of 1944, more than 90% of Albanians were illiterate. Whereas now, the eight-year school is mandatory.

One in three Albanians today sits in school desks. The average age of the population is low. Together with the Albanian province of Kosovo in neighboring Yugoslavia, Albania records the highest birth rate in Europe. Every year, the population grows by 2.1% (West Germany, for comparison, has a rate of: minus 0.1%).

The fear of war is seen everywhere. Even at a holiday and tourist resort on Durrës beach, bunkers are seen, and in the offices of post offices and factories, lamps are hung that, on “day X,” show what kind of danger threatens: from the air, chemical, bacteriological, or atomic.

We also visit a knitwear factory, a rug workshop, and another for the production of copper wires. Karl Marx would have had a heart attack on the spot. The working conditions here remind you of the worst times of the first steps of capitalism.

The toxins produced by the factory’s waste pollute the entire surrounding environment. The word “environmental protection” is unknown to Albanians. Such a word doesn’t even exist in their dictionary. “Production,” is the imperative of the time.

The low net wages (taxes on them have been abolished) are enough to satisfy daily needs. Qualified workers earn 200 to 250 marks per month, but they also have to pay rent for state-owned apartments.

Academics and officials manage to earn up to 400 marks per month, and to pay the rent for their houses, they have to work two days. No Albanian should earn a salary that is more than double that of the simplest “comrade.”

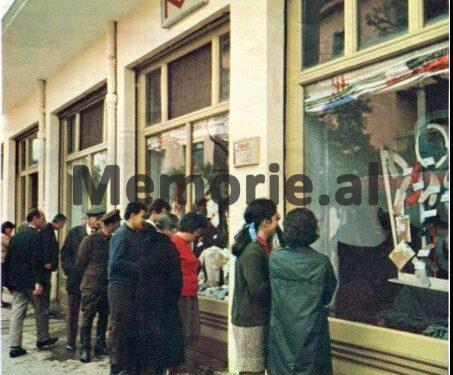

Here, socialism has truly eliminated all class distinctions. In stores, something will always be missing. Somewhere wine, somewhere mineral water, somewhere salami, and somewhere cheese, and the meat and fish shops remain closed until two o’clock, but in any case, something to eat can be found everywhere.

Armies of beggars, child gangsters, or the risk of starvation, Albania does not know, in contrast to some third-world countries like Brazil, or India, which, although thanks to foreign loans have reached a considerable degree of technological development, have nevertheless not been able to withstand the poverty in their countries.

Thousands of slogans echo the party’s successes on the 46th anniversary of its founding and celebrate the victories of the revolution. And hundreds of memorials, martyrs’ cemeteries, and museums commemorate the fallen that enabled the Albanian people to achieve these successes.

During the Second World War alone, 28,000 Albanians died, or rather “one martyr for every square kilometer of the homeland.” The houses of these heroes of the people have been equipped with commemorative plaques and signs.

Their shoes and pens are displayed in museum showcases and preserved as relics and even excavated bibles where the revolvers of guerrillas and partisans were hidden. Instead of talking about Italian and German occupiers, museum guides more often talk about the fascists and Nazis they defeated.

Ideology must align with the day-to-day state policy. For a long time, Tirana and Rome have exchanged ambassadors again. Official Bonn is now also represented by its own representation in Tirana.

Albania, which does not want to have anything to do with Washington and Moscow and which is still “bickering” with Beijing, is in urgent need of new technology for its now totally outdated industry.

“Made in Germany” is in high demand. Ever since the establishment of diplomatic relations, there is great hope for West German aid in the fields of mining and industrial processing, and scholarships are expected to be granted to Albanian pupils and students.

The first German technicians have meanwhile started work in the country, with the good will of the party’s reformist leader, Ramiz Alia, who took over Enver Hoxha’s legacy two years ago.

Long live comrade Ramiz Alia!

Albanians, who are fond of life’s pleasures and who take advantage of every evening under the setting sun, fill their main city and village boulevards and streets to enjoy a peaceful afternoon stroll. They have high hopes for an improvement in their living standards from their leadership.

Some want more plastic bags and lipstick, while others want sunglasses and motorcycles, which are seen as symbols of those who have family members abroad.

Almost every family owns a television, and since the Italian channels, programs, and commercials can be freely received, the “comrades'” hunger to enjoy a little more daily luxury is growing.

“Bon giorno,” “Va ben.”

The Italian mixed with gestures and hand and head movements entices us to follow a teenager from the ancient city of Elbasan. “Chiesa?” – Church. He wants to secretly show us a church in exchange for a piece of gum.

Religion in Albania is still a taboo subject. For centuries, Albanian Muslims, Catholics, and Orthodox have often clashed over political motives.

The divisions once went so far that the poet and writer Vaso Pasha, in 1860, made a passionate call to all Albanians: “Do not look at churches and mosques; the faith of the Albanian is Albanianism.”

The party also relied on this historical appeal when it advocated atheism in 1967. All churches and mosques were closed, or converted into factories and plants, warehouses, and museums. Crosses and crescents were broken, and priests and imams were sent to labor camps.

Only in 1982 was the total ban on religious belief somewhat tolerated: whoever felt they absolutely had to pray could only do so in their own home and completely alone, and not in the presence of other family members.

And this did not suit many people. So, in the ranks of the people, it is felt that a silent protest has begun. After every protest (so we have heard), the police on the streets now often find hand-carved wooden crosses.

And in the industrial city of Korçë, in southern Albania, we photographed the closed door of a mosque, on which some unknown persons had scratched crosses during the night. A dangerous act of courage, as the “guardians of order” can be found anywhere. They rarely forget. / Memorie.al