By Ahmet Bushati

Part thirty-eight

Memorie.al/ After the flag was altered in 1944 with the addition of the communist star, Shkodra transformed into a center of resistance against the regime, paying a high price for its tradition of freedom. By April 1945, high school students, already feeling betrayed by the promises of the war, gathered to oppose the new terror that imprisoned and killed innocent people. Communism turned Kosovo into a province of Yugoslavia, while Shkodra was punished for its “historical crime”- its defiance against invaders. The “Postriba Movement” became a tool to suppress all dissent, plunging the city into an unprecedented spiral of suffering: imprisonments, executions, and the destruction of families. The high school students, alongside citizens, became symbols of resistance, while some “young communists” turned into tools of the State Security, leading to expulsions, imprisonments, and internments.

Four times, Shkodra rose in armed rebellion, but history forgot these battles. This book is written to remember the countless prisoners, the tortured, the killed, and the parents who suffered in silence. It is a warning against dictatorship and a plea for future generations not to forget the sacrifices made for freedom.

Continued from the previous issue

In the Footsteps of a Diary

But after more than a week, with little strength gained from the “basement”, I walked through the large prison yard with the only help of a policeman and, as soon as we entered the prison corridor with him, we met the policeman Qani, the good and serious Qani, who was standing with an automatic rifle in his hand. I think he was from the Fier village. My sudden appearance made an impression on him, and how can you say, he seemed to be angry with himself. He suddenly turned his back on me and began to walk, muttering in a nervous tone every word, whether Turkish or Arabic, that were used at that time, like “Allah bin belaversen…”, etc., and, turning nervously towards me several times, he would shout in an even louder voice: “What a slave you were, what a slave you were, that you took yourself by the throat”?! etc.

He was sorry to see me in that condition again, with the policeman beside me with a rope in his hand. During that last week that I had not been in the dungeon, he had apparently believed that the interrogators had finally given up on me and that I had been transferred to some other prison. It is our duty, whenever the occasion arises, to affirm that there were policemen who followed our sufferings in silence and with pity, for whom it was our duty as prisoners of those times to show our gratitude, as well as to despise those bad policemen who, without need or desire, added to the weight of our sufferings even when such an attitude was not necessarily required of them by their superiors.

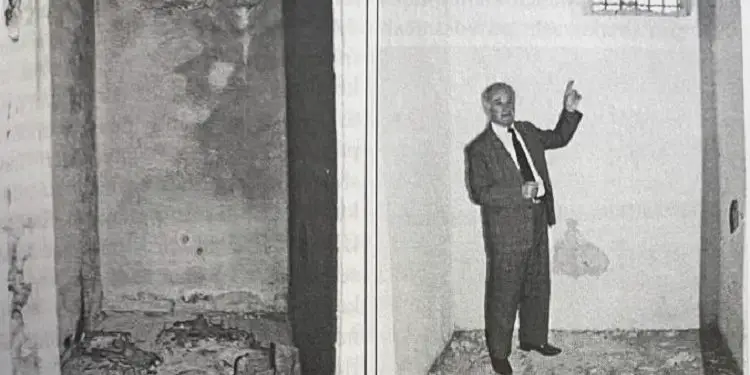

The first twenty-four hours in dungeon no. 12 would have been enough for me to return so quickly to my previous state. It was the beginning of October and until its end, – the time when I would finally be saved from suffering and death – another ordeal of suffering would pass, although to describe it, as similar to the previous ones, only a few words remain to be added: Crushed to death as I was, they would no longer take me out to the W.C. in the evening, but only in the morning. I would not react to anything.

Small mice, which would descend from the ceiling several times during the day and night to go to a small container long abandoned with completely frozen “bread with milk” waste, would traverse my body from head to toe and back, again taking the same route, without having received even the slightest reaction from me. For most of the time, I would not be at all myself, except for those now familiar occasions when the faces of Ali Xhunga, Ismail Lulo, or someone like them would appear before me. My actions during this entire period would be instinctive, to the point that I would not know whether I was a human being, or an animal with a human conscience, or where I was.

Even Ali Xhunga, not excluding hanging, had given up on me. He did not appear anymore. As one might have guessed, in order to be in order with his superiors and them perhaps with others, he had abandoned me in the arms of a slow death. During the entire month of October – if I am to believe my state of severe hallucinations until the end – only once did Ali Xhunga put me in the dungeon, and on that occasion, he would stand longer than ever before in front of me, with his hands tied behind his back and without speaking, but also without anger on his face. Only when he made me come out of the dungeon, in a serious but gentle tone, would he speak for the first time: “No one has suffered like you are suffering. Get over yourself”?!

Ismail Lulo could have been a born criminal and carried out his duty as a loyalist of the dictatorship, in any case, to the end and willingly, but the truth is, until then, he had never teased me with words. Starting from this recent time, he would tease me with the pleasure of a true sadist, as he watched me at the end of my life. For example, during those days he would say to me several times: “Hey, you’re still alive, aren’t you?”; or “You didn’t die today either, aren’t you?” etc., etc., like these, while I, among other things, would say to him: “As I suffer today, you will all suffer one day.”

One evening, as he opened the door for me, he began to speak, but because of the stench of my body, he suddenly closed the door, and without leaving, from behind the door and also continuing to spit on the ground, he would say to me: “Now there is no more. The end has come for you! I am dying”! And I, so that the other prisoners could hear, would answer him with great difficulty and hesitation, but in a sufficient voice, “I am really dying, but my friends will take revenge on me, killing you all, you first”. etc., etc., words like these.

I will never forget how these last words of mine, which he was probably hearing for the first time from a prisoner, apparently made an impression on him, and perhaps for the first time, they made him think fearfully about the fate of his life, because he would come back to my door once more, and as if out of curiosity and as if laughing, he would say to me: “How, how, tell me again”?! And I would repeat to him exactly as I had said to him the first time.

It was the last days of October and, whatever my condition, I could hear the rain that was falling continuously those days. It occurred to me that several times I was communicating for the first time with an aunt of mine, who had come to Shkodra those days from Tirana, where she lived. But the most important fact of those last two weeks would be that during most of the time, I would not consider myself a human being, but a horse loaded with two baskets of grapes on its back, and that due to the great thirst I had, I would constantly try to bring myself to the point of bringing my head from one basket to the other, so that I could catch a bunch of grapes, but that, like the case of Tentacles thrown to the bottom of hell for punishment, who every time he approached to drink water, the water would be removed from him, so that I too would not and would never manage to catch such a delicious bunch of grapes, even though it constantly seemed to me that I had it so close!

I didn’t know how to enjoy a happy “epilogue”

For the policeman who finally untied me from the ropes and dueled with them hand to hand without speaking, I, due to my lack of awareness, showed no interest at all. Still handcuffed and not understanding anything that had happened to me, I instinctively lay down under the door, where I had been hanging, and fell asleep immediately. When I woke up – probably in the morning – after a few hours of deep sleep, only for a moment, and again not knowing day and night what had happened to me, the only action I took on that occasion was that I slowly moved away from the door, took a seat somewhere against the wall, and before falling asleep again, I saw that it was night and that the policeman had forgotten to hang me. I also saw that I was who I was, not a horse. Without being able to think about anything else and, without wasting time, I fell asleep again.

The next morning, for the first time in three months, my broken hands were freed from the shackles, and for the first time in three months, I was given my daily food and sleeping bags. However, I felt no joy, and I would not feel it for several more days. I had reached the point where nothing could revive my physical or mental state in the slightest. Surprisingly, I remembered to look in my trouser pockets for the hazelnuts, and to my regret I noticed that they were gone. I continued to be very tired. So deep was the apathy that would hold me back for many days, that I did not know how to rejoice at the salvation of my life, and also did not remember that a life of hopes and dreams lay before me, like the nineteen-year-old I was at that time.

I spent the whole day lying on the mattress like a living corpse. I showed no interest in anything. I could hear with one ear, although not well, and with the other not at all. Even though the days were passing one after the other and food was coming to me regularly for days, still, my physical condition was improving very slowly. Even slower would be the healing of the wounds. There was no talk of any medicine or even the slightest hygiene. Almost a year without being washed, my body continued to stink and was in danger of being infested with worms. I would have turned pale, my whole body and head were covered with scabies. It would take many more days until I could straighten my body and not walk with my arms and legs like when they were hanging me.

Within two days, from the state I had been in from standing for so long in the damp cement, I would completely deflate, and only then would I look with surprise and embarrassment at the protruding ribs that were easily counted. I would be impressed by the appearance of the elbow joints, kneecaps, and pelvic bones, which in my extremely thin body seemed extremely enlarged and deformed. I would say that physically I was in the state of the skeletons of those Jews in front of the crematorium that we used to see in movies. Or were my limbs not very thin! On my thighs and arms I would notice how many times with surprise, how from their great thinning and the shrinkage of the skin, the veins had gathered and joined in places and formed like thin, bright lines in a dark green color. My teeth were very loose and so were my fingernails and toenails, they almost fell out.

After about a year someone would tell me that the latter had been caused by the disease scurvy, as a result of a pronounced lack of certain vitamins. Unlike other times, when after each torture I had eaten with great appetite, this time, even after many days that my torture had stopped, I would continue to eat very little and without taste.

If I had not known that Enver Hoxha had annulled the divorce with Yugoslavia four or five months earlier, and also about the “turn” that he had announced with such great fanfare – as a result of which I had escaped further suffering and survived – if I had not known about anything for many more days, I would have waited for the tortures to resume, and in connection with them, I would have said to myself over and over again: “How unfortunate that they had stopped the tortures! Everything would have ended by now”!

The months of November and December had passed, and I continued to remain in the solitude of my dungeon, undisturbed by anyone, and as always, without removing from my mind the unpleasant idea of the resumption of the tortures. Although two months had passed without torture, I continued to be physically weak and to feel very tired. Due to lack of treatment and hygiene, the wounds all over my back, as well as between my wrists and under my armpits, on my arms and even between my knees and below them, continued to be unhealed. I could hear poorly in one ear, while the other ear continued to have a rather thick ring around it.

I did not know what was happening outside my cell, and I was only interested in knowing which prisoners were around me, whether any of my friends were there, and whether the others I had once noticed through the crack in the door of cell no. 9 were still there, and finally, in knowing if there were any other students who had been arrested.

After a year, an unexpected encounter with the evil Sirri Çarçani

Since one Sunday morning, probably early January 1949, when the thick voice of a man who had suddenly entered dungeon no. 1, wanted to remind me of a familiar and evil man, who for once I was not able to identify who he could be. However, it would not be long before I recognized Sirri Çarçani in that characteristic voice, which I had not met since a year before.

He and his entourage were passing from one dungeon to another and I, although with poor hearing and still not knowing anything about the “turn” made by Enver Hoxha, but meanwhile, his softened words to the prisoners of the dungeons, were pushing me to believe that something had changed politically. As I would later find out, Sirri Çarçani himself had also changed, although like a wolf’s fur and that he had been delegated from Tirana to bring the hypocritical message of softening and mercy to the prisoners.

It seemed strange and disgusting to me to hear how he, from a charlatan and arrogant man as he had been and in reality was, was speaking to the prisoners as he normally speaks to a human being. You know that Sirri Çarçani, as one of the most typical communist interrogators, cunning, cynical, brutal, arrogant and banal that he was, at the time when I was listening to how he was addressing the prisoners one by one, with; “How are you”? “What do you need”? Or when he told them humanly: “Don’t be upset”! And “Your work will be looked at”, etc., I wanted to vomit.

When he, as always after the turn, before entering my dungeon, I heard from outside how he asked Ismail Lulo: “Who is here”? and after the latter told him my name, he ordered in his familiar tone: “Open”, and with the first step he took inside my dungeon, he also pointed his index finger towards a corner of the wall under the ceiling, shaking it forcefully several times and as always with a face that would ruin you, he would address me with great arrogance:

“What do you remember?! There, there in that corner, we will hang you! You have suffered a lot, you will suffer even more. We will not let the brave pass here”! He spoke other words and I, after him, without forgetting anything from the story I had had with him a year before and without having forgiven him anything either, suffering and filled with anger as I was, could hardly wait to answer him like that beast with the face of a monkey, he did not want it and as if he did not expect it: “Do what you want, I will never go to trial”! When he was leaving, apparently remembering the mission that had brought him to my dungeon and without turning to face me at all, and also without giving up his harsh tone, he asked me briefly: “Do you need anything”? And I, who did not want any favor from him, answered with a simple “No”! And he added coldly afterwards: “Will you write to the family”? And I again a “No”!

This was the evil Sirri Çarçani, who, even after so much time, was finding me where he had left me a year earlier, battered by torture and still in a dark dungeon, and even though when he entered the dungeon he saw clearly how I stood up with difficulty, he still had nothing that could touch his conscience to break him to the end, from his criminal work that he had been carrying out day after day, for years! A few days later, in connection with the above visit, Nush Simoni would tell me that with him, there had been three of my former investigators, namely; Lilo Zeneli, Xhemal Selimi and Ali Xhunga, but that on that occasion, they had preferred not to enter my dungeon.

A very enthusiastic evening for me and the prisoner Nush Simoni

During those last days, it occasionally occurred to me that through the iron cage above the door, they were entering my dungeon as if they were detached bundles of words and sentences, fragmented and unfinished, that seemed to be floating in the air and that also seemed like the whispers of invisible spirits. I was unable to perceive them as I wanted and, sometimes, I suspected that they were blocking my ears. “Could they be auditory illusions as a result of the condition of my ears, still unhealed”?! – I would say to myself several times. Sometimes they would even sound to me like indefinable vibrations of the air.

It was an evening when all doubts would finally be dispelled and I would assure them that they had been real conversations of people, who, in low tones, were talking to each other from one dungeon to another. Moreover, that same evening, my ear would once catch my name. And when that call was repeated a couple more times, I no longer had any doubt that someone near my dungeon really wanted to talk to me. “How is that possible?” – I said to myself.

It had never happened that prisoners communicated with each other there! For a moment I thought it might be a provocation, but in the meantime the call was repeated once more and I then sprang to my feet and headed for the door, where I wrapped my sleeping clothes and climbed on them, in order to be as close as possible to my unknown interlocutor, who, as I would soon learn, happened to live next door to my cell and was called Nush Simoni (Father).

The joy I felt as he spoke to me is indescribable. It was the first time in a year that a person had spoken to me in a friendly way: “What’s the point of calling you! Are you completely deaf?” – were the first words that Nush addressed to me instead of greeting. I wonder how many times I forced Nushi to repeat the words he had once said to me, since not only was I hard of hearing, but also because Nushi had the left ear, with which, as is known, I could not hear at all. Then that Nushi spoke very quickly.

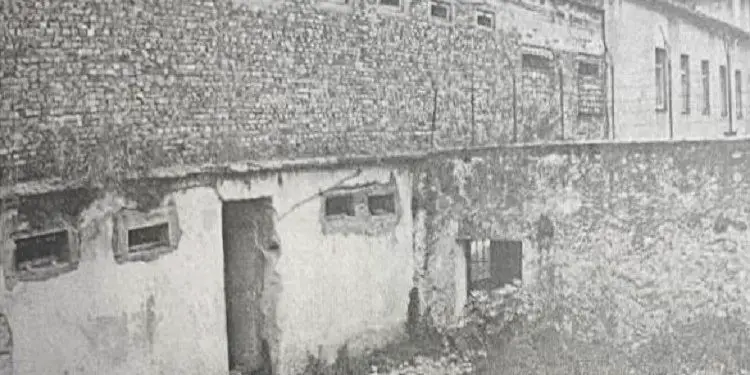

Nushi Simoni stood up! He had spoken quickly all his life and would continue to speak quickly for another couple of years, until one day he would die in the isolated room for tuberculosis patients, there in the Great Prison of Shkodra. My cell with Nushi was separated by a thin wall that gave off a lot of acoustics, through which Nushi, with his fist on it, would direct “phone calls” to me, until late at night. Without further ado, Nushi told me that night the names of many prisoners who were there, who had generally been arrested in the last four or five months, and I had generally not even heard of their names.

Many of the prisoners from our side of the corridor were chatting with each other, calling each other by nicknames. Nushi had the nickname “Devolli”, then the others had nicknames such as; “Tigri”, “Shkoza”, “Flamuri”, “Alqishë e Madhe” and “Shipja e Vogël”, “Zjarri” etc. In this meeting, Nushi asked me to give him a nickname, and I said to him, for fun, “What nickname, you beautiful people kept it to yourself and I was just called “dreq”?! I said it just for fun, but Nushi liked it so much that on that occasion he would start calling me “Dreq”, and so on, and so did the others.

Every time a prisoner spoke to another prisoner in another dungeon, a third prisoner would take over the role of guard from the police. So, while the first two were talking to each other, the third, climbing on top of their sleeping bags, would keep the policeman under observation, and if he said; “The river is moving” the interlocutors would immediately stop talking and lie down on their beds, and sometimes lie down as if they were sleeping, for any control surprising on the part of the policeman, who in such cases, would head towards the place where they were talking, but who generally, without having managed to identify them, with the exception of Nush Simon, who did not know where to go, and who, without having finished talking to one, would start talking to another, often without even having time to get the guard out.

There were times when Nush would call one of his fellow prisoners, without having thought about what he would say to him, and when he called him to ask Nush; “What happened to ‘Devoll'”?, Nush for his part, as unprepared as he would be, would answer with indifference: “No, no, you’re doing it in vain”. Nush Simon was clever, very clever, the cleverest of all.

Since he wanted to talk to one person at a time, and often without even raising his guard, it happened that the policeman would suddenly appear right in front of Nushi, saying: “So, did I catch you?” – and Nushi would deny it even in such a flagrant case, even though that policeman had his hands and face between the bars above the door. It happened that even when an officer who had come there to report such an incident stood between the policeman and Nushi, Nushi would still deny it, perhaps with more courage than if he were asserting a truth. Or he would not get a hundred words out of his mouth in a second, without giving the policeman or the officer himself the opportunity and time to speak.

“By Christ, comrade officer, it’s not true; this policeman has confused me with someone else”! – Nushi would quickly swear in his thin voice, and as soon as he saw the policeman who wanted to speak, or even the officer himself, Nushi would intervene in front of them: “Don’t ask me, don’t speak! It’s not true, I was even thinking about it at the time, this man – for the policeman – saw me when he opened my window”, – etc., etc., tales that Nushi was able to create on the spot. So Nush Simoni, even though we fell into the policeman’s trap, word for word and deed for deed, would escape most of the time, but of course, not always. Memorie.al