By Nini Mano

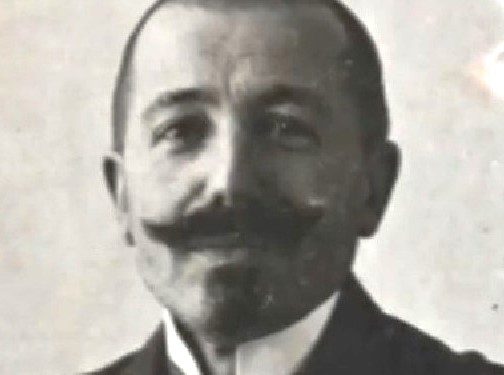

Memorie.al / Sotir Kolea, considered by many scholars as the last representative of the Albanian Renaissance, died on July 3, 1945, in the city of Elbasan, at the age of 73, after a life entirely dedicated to the Albanian cause, beginning in his youth.

Kolea was dismissed from his post as Director of the National Library and Museum by the Minister of Education at the time because he never remained silent about any of the scandals he encountered in the administration of the era. They did not even grant a pension to the man who, within nine years, managed to establish the National Library on scientific foundations, allowing its readers to always find the doors open, instilling in them the love for reading and for the Museum, which he contributed to enriching with considerable funds for national culture, language, and history.

The bureaucracy and inefficiency of the ministries of the time did not impede his determination to secure funds to enrich the Library and the Museum. His persistence in dedication to the Library made it possible for young people to participate in large numbers. In 1928, 459 books were read, and 1,785 readers participated.

In 1930, 3,021 volumes were read. In 1931, 5,805 volumes were read at the Library, and 11,280 readers participated. “Many benefactors have kindly donated various valuable objects to the Museum,” Kolea himself declared in a report in January 1928. These objects numbered 1,851 pieces.

On May 15, 1929, while searching for Albanian books printed in ancient times, he received a reply from the British Museum of London, from the printing department, which, among other things, stated: “We do not have books by Gjon Buzuku, Luk Matrenga, and Pjetër Budi. (Speculum confessionis)… but, we do possess such books as: Pjetër Budi – Christian Doctrine of 1664 Ni 4051, d 5;… we have the following books in Albanian: P. Francisco Maria de Lecce – Grammatical Observations on the Albanian Language, 1716; Johann Thunmanus an 1774 edition; from Daniel Voskopoja ‘Dictionary in 4 languages of 1902’.”

In 1929, Kolea reported that: “Professor Gustav Wiegand donated 100 volumes to the Library, placed in a box,” while other donations included geographical maps such as “The Coasts of Epirus – the Narta and Preveza section,” “Part of Turkish Albania with Montenegro, Venice 1789,” “Dalmatia,” “The Course of the Drin and Buna Rivers,” “La Scanderbeide, heroic poem (Signora Margherita Sarrocchi), Rome 1623; “Pouqueville – History of the Regeneration of Greece,” Brussels, 1843″; Gjon Buzuku’s Missal (Mesharin), an Albanian work, with images from the Vatican, printed in 1555.

He enriched the Library in 1929, paying the sum of 80 gold francs, in Shkodër, for the book “History of Gjergj Kastrioti ditto Skënderbeu,” by the author Gianmaria Biemmi, published in Brescia in 1742. Kolea chose the city of Elbasan as the place to live and work, developing, studying, and publishing all his life’s research, solely for Albania, to which he dedicated his entire life and wealth. He lived an isolated life with little exercise, partly because his health was slowly deteriorating. But the pen never refused his hand, until just a few days before his death.

He was buried in the Elbasan cemetery, honored by many friends, acquaintances, and admirers. But, after his funeral, Kolea’s closest relatives accidentally encountered his rented house in the “Kala” (Castle) neighborhood, not only with a door locked and sealed but also with an official from the Elbasan Justice of the Peace, who did not allow them to enter, reasoning that: “Documents of national importance are present here”?!

Neither Kolea’s nephew nor niece, upon returning to his house after 4 months, managed to discover what had happened to all the materials, documents, manuscripts, and correspondence of their patriot spanning a period of 57 years, including communications with other Albanian patriots, politicians from the most powerful foreign countries of the time, in Europe and the American State Department, between 1909 and 1943.

Surprisingly, the relatives found almost none of Kolea’s personal belongings, not even his beloved typewriter, with which he had typed thousands of pages, being part of many works and studies in various fields.

None of Kolea’s relatives ever knew the reason for the mysterious disappearance of the materials from the house where he lived for about 15 years. Why was the house where this wise man spent his last years sealed? This enigma and mystery haunted Kolea’s family for many years.

And finally, as Kolea’s great-niece, studying and working on a monograph about him, with the “Sotir Kolea” fund, one of the largest funds currently owned by the Albanian state, I was amazed to read about the interventions and violations with which the communist state denigrated Kolea’s work after his death.

It is frightening how the state, which was created through war, in the name of freedom, managed to enter the most intimate and secret places in the possession of the patriot Kolea, his observations, studies, even a political testament, written by him on March 17, 1935, in Tirana and submitted to a notary in Elbasan, sealed in a large red-stamped envelope with four stamps, with the words: “Open after 50 years.”

Who was Sotir Kolea?

Sotir Kolea was born in the “Goricë” neighborhood of Berat on September 4, 1872, into a cultured, intellectual, and merchant family. He was the eldest son of the lawyer Kristo Kolea, who had worked for a long time as a legal advisor for the Balkans for the French Tobacco Monopoly in the Ottoman Empire, “La Régie Des Tabacs.” He was born to inherit the wealth of one of Berat’s oldest and most cultured noble families, but life, at a very young age, changed his destiny.

After primary school, at only nine years old, he was placed in a Monastery with his uncle Ilia Kolea, who was involved in the tobacco trade. After completing his studies at the Greek Lyceum, he was appointed as a tobacco clerk in Ohrid. From there, he was transferred to Greece, to Drama and Kavala, where he lived and worked from 1899 to 1902.

Later, he settled in Egypt, where, after a period in the tobacco trade, he dedicated himself entirely to the turbulent life of politics, advocating for Albania’s independence and its territorial defense. At just 19 years old, he spoke eight foreign languages: Greek, Turkish, Latin, French, Bulgarian, Italian, Romanian, and Spanish, to which English, Arabic, and the local language of Madagascar would later be added.

Before turning 20, he joined Albania’s patriotic independence movement. In 1911, he was appointed secretary of the association “L’Unità” in Egypt, and for 15 years, from the end of the 19th century until the first 10 years of the 20th century, he distinguished himself for his active contribution to achieving Albania’s independence, organizing and leading patriotic associations in emigration, debating with European politicians on the national issue, etc.

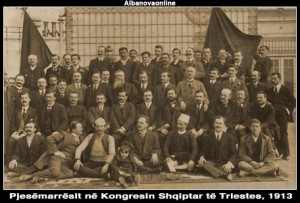

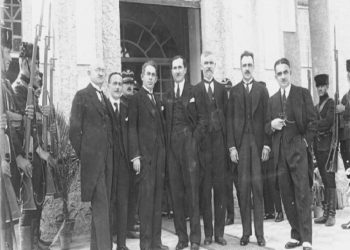

Between 1912 and 1920, he set aside his personal concerns and mobilized to serve the nation. Kolea was involved in diplomatic and journalistic projects after independence, supporting diplomatic services and representing the nation in various European chancellors. In 1913, he was among the organizers of the Congress of Trieste.

In a note of protest addressed to the President of the United States, dated May 13, 1913, Kolea wrote: “The sacrifice of Vlora would make Albania’s independence illusory and would jeopardize the existence of the ancient Albanian people.”

In 1914, after meetings in Brindisi and Lecce, Italy, with Albanian patriots, Kolea moved to Lausanne, Switzerland, where in 1915 he edited the French-language newspaper “L’Albanie,” known for its special merits in making Albanian issues accessible to foreign readers. He was appointed a member of the Albanian delegation to the Paris Conference and to the Franco-Albanian Administrative Council in Paris.

In 1920, the provisional government of Vlora also chose Sotir Kolea, a known activist and patriot of the Egyptian colony, as a member of the Albanian delegation to the London Conference. However, he chose not to participate due to personal distrust of some delegation members, and he requested that the delegation be led by Prince Fuad of Egypt, a prince of Albanian descent.

In his convictions, Kolea remained faithful to the idea: “The interests at stake are colossal” and that “the efforts of the Vlora government could not have succeeded without a figure with diplomatic influence leading the Albanian delegation,” such as the Prince of Egypt, with Albanian blood. During the period of political turmoil, Kolea had embraced the idea that; “No foreigner can do for Albania what someone of Albanian origin can do.”

After the 1920s, realizing the great misunderstandings between the various Albanian political forces, the thirst of each for power, tired and disappointed, Sotir Kolea devoted himself to his private life. In a letter addressed to his friend, Midhat Frashëri, on March 25, 1920, Kolea wrote: “In this blessed Albania, I fear it will become a habit for all governments, like those we have had until now, to eat, drink, wash their hands, and leave.”

During this period, he moved to Madagascar, and later to Marseille, France, where he worked in trade. On December 20, 1927, Mit’hat Frashëri was the first to inform him in a letter about the decision of the Council of Ministers, appointing Sotir Kolea as the director of the National Library and National Museum. In 2002, on the occasion of the 90th anniversary of Independence, President Alfred Moisiu awarded Sotir Kolea the “Gold Medal” of the “Order of Naim Frashëri.” / Memorie.al

Translated and prepared by Adela Kolea