From Ylli Polovina

Memorie.al / Dhimitër Papastefani in the fall of 1963, he had just finished his studies as a doctor in Tirana and had been performing the task assigned to him for a very short time. He was a health inspector in the district of Berat, the early birthplace of his family, even though his father, a merchant of manufactures for two generations, then went to Elbasan and Kavajë, finally settling here after the war. While one day inspecting the town of Ura Vajgurore, at that time together with “Stalin Town”, part of the same administrative district, he left an inspection report. In it, the sanitary worker, whose name was Roza and who was Italian, was reprimanded for several shortcomings. When she did the re-check, she noticed that the woman who had been warned of a punitive measure had not yet implemented all the tasks left. So he did not hesitate to cut the fine: five hundred lek. At that time it was one eighth of the monthly salary.

After a few days, his two main leaders called him to the office. While he was waiting to be thanked, they interfered with the opposite. They told him that Roza stood out as a good employee of the health service and that the defects found were of no importance. The superiors proposed a new control, but which they would carry out together. That’s how it happened.

As the verification was quickly completed, the Italian invited them to her small two-room apartment, and in the corner by the window a table began to be prepared for lunch.

Everything seemed to the inspector to be contrived, but he did not make a sound. At this moment a beautiful girl entered the room Fax. She was black and had a sparkling look. He started renting to friends. Roza explained that she was the daughter, the only girl. Her name was Karmen.

For Papastephan, this moment would pass without leaving any scars if suddenly his heart was caught in the throes of an irregular beat, as if it were writhing. His gaze was horrified. When the new light came and everything before his eyes became clear, he noticed that the image of the graceful girl was no longer in front of him, as a normal human size, but was shrunk and made like a glass doll. He had entered the baby and was sitting there, as if he was waiting for an intimate meeting with her.

They got engaged very quickly and together with this event he learned that not only Carmen’s two brothers, Guido and Encio, but also her father, Milto Xhimitiku, had spent political imprisonment. While the first two were already free, the person who would have been his father-in-law was no longer alive. He died in the Prison Hospital. When they asked for the body, the director himself, who wanted not to be harsh, told them that this was not possible. It was an official rule. He added that there would be a grave for the dead anyway, but they should not know where it was. They didn’t even have to ask for it.

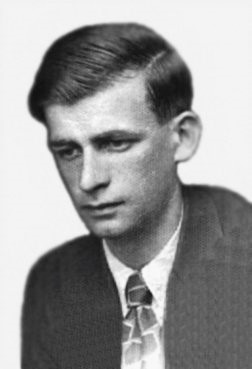

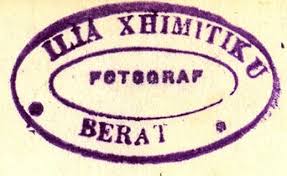

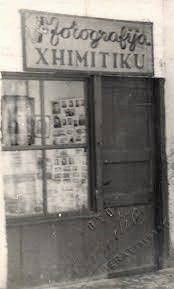

When Karmeni and Roza told him this story, Dhimitër Papastefani did not ask for other details. He had to protect and save his love, as well as his future family. They did not show him the first days of the official engagement or the photo of Milto Xhimitiku. When he started the ritual of visiting his fiancee’s relatives, in the waiting room of her uncle, Lilo Xhimitiku, who was the most famous photographer of the city, hanging on the wall, Dhimitri’s gaze remained on the picture of a man with brown hair gray and with a thin moustache. This was a very familiar sight to him. He could have seen and touched that man over thirty times.

It was one of the corpses they used in the faculty. He had fixed it in his memory since 1959, when he had just started his studies for Medicine. In the great hall of the monk, while everyone’s eyes were burning from the smoke of formalin, the elderly employee named uncle Naun, with an iron pick, pulled out the corpse they were looking for from the tubs, where the bodies were floating.

They had no names, not even numbers. They were identified by some visible physical characteristic. So the man who was already seeing him at the fiancee’s uncle’s house and who definitely had to have a close relationship with them was called “the one with the spic moustache”.

In all four years at the faculty, Dhimitër Pastepefani noticed that the corpse, preserved very well by formalin, was the most favorite among the students. This happened because his body was thin and weak, every detail was noticeable. In the first year they learned about bones, in the second year about blood vessels and nerves, about muscle groups as well. The wet corpses were laid on the back of a long table and, under the guidance of a specialist; the participants in the lecture were given the necessary explanations.

Then, with the tip of the pincers, the students, to practice practically, grasped the bone nodes or blood vessels one by one and pronounced their scientific names. But in all cases this was done very carefully, very gently, so as not to damage them. Any mistake in the use of physical force on the corpse was very expensive.

Expulsion from the faculty was very few. For those corpses, implying that the state had no mercy for them, it was mostly said that they had been enemies, foreign spies or members of gangs ambushed for sabotage and terrorist acts. Sometimes it was rumored that among them there were ordinary convicts, abandoned by their families or even unidentified.

That late afternoon, while on the courtesy visit, Papastefani did not ask the question that; what did that picture have to do with his fiancee. He did this as soon as he was alone with Carmen She. With a sudden breath hold, he answered that it was his father.

Dimitri was numb. For several minutes he did not feel that he had a body or limbs. Then, taking care not to cause him any trauma, he began to explain the truth. That same evening they also told Roza. At home a bomb dropped in the middle of the room would be less terrifying than that news.

***

Milto Xhimitiku was arrested during the night, together with his two sons. It was April 1950. They were waiting for the Easter celebration, and they even took a happy family photo. Those moments Roza was in the hospital, the third shift. Milto begged the captors who came out of the darkness if he could speak to his wife. She definitely had to come and get the six-year-old girl; otherwise the little girl would be left behind. The uninvited visitors did not object. Roza arrived as if she had eagle wings. Then the house immediately emptied.

The three of them, with irons on their wrists, fled in silence. From this moment, Karmeni remembers only the noise of the small salon and the voices of the speakers, which seemed to come from the bottom of a cave. Everything else, from the great shock, perhaps even as luck to save him from some devastating psychic trauma, has been finally erased. Instead of the appearance of things, when he asks, the young man awakens only a consciousness of falling into the abyss.

They were sentenced in September. From ten years sons, twenty Miltos. Double of the father, “because you did not come to denounce them”! Roza had dictated in time that Guido and Encio, together with three other young men, one of whom must be a state spy, be locked in the room. And every time that happened, he broke up their meeting, chasing them away with a broomstick. But in the event that her two sons could have touched the namuzi of the regime somewhere, her husband had not interfered at all. He by nature could not do such dares.

Most of the household furniture was confiscated and the two women, left without the rest of the family, lived for some time in the hospital. They soon removed them from Kuçova and placed them in Berat. Roza had been there for two decades, starting from 1926, when she came from her homeland with the Albanian student, Milto Xhimitiku, in her arms. They met and fell in love in Naples, in her aunt’s small pension-hotel.

That year she was employed as a municipal midwife, while her husband started working as a translator for the Italian military attache, Gustavo Gambara, colonel. When he left in 1932, he recommended Milton to the oil extraction company AIPA in Kučovo. Here he started the profession of accountant-treasurer, almost that of an office manager. Roza followed him, along with the children. She herself worked as a midwife. Before the war ended, Guido and Encio went to Italy and completed school.

Now that the year 1950 was passing and the halved family was taken to Berat, the local authorities to shelter them brought the condemned directly to the floor of a private house. Until recently that floor space was used to keep a cow. As soon as the people in power left, the master of the house took them upstairs to his family’s three rooms and told them they could choose one of them. They would never live in katua. That’s how it happened.

Italiania Roza had to wait for the release of her husband and two sons from prison. The years were flying by and she was optimistic that one day she would have all three by her side. Milton to enjoy as a husband and two daughters to marry. In the meantime, sometimes even with little Karmen, she used to go to her husband’s prison.

After some time, he made his way to the labor camp in Zadrimë, Shkodra. When Milto, seriously ill from a cold and with quite aggressive diabetes, was admitted to the Tirana Prison Hospital, she brought him food as much as she could economically and as much as was allowed. He fought with all the strength of his soul to improve his health. But he died in 1958.

For years, Roza had tried to remind the authorities that during the war both had greatly helped the partisan movement. She had secretly taken out with her small bag, amid the strict control of the Italian hospital, alcohol, iodine, bandages, leucoplast, tablets and various medicines. She had also tried to remind them that her husband had done for the partisans what he would never have thought of under other circumstances: theft.

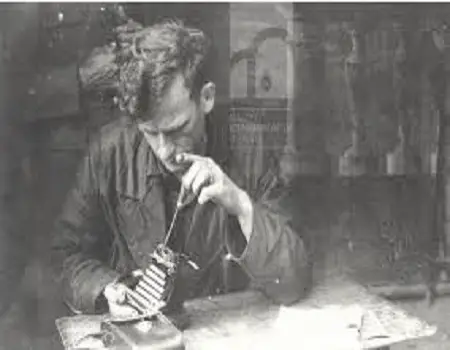

Milto Xhimitiku, the financier with exemplary correctness for every penny of the AIPA account, had illegally taken a typewriter and set off for the mountains. He had taken her out of his office. The Italians dictated to him and immediately imprisoned him. He did not accept the charge. After two weeks in the dungeon, because they couldn’t prove it, they released him. They returned him to work, but now at a lower level: as a simple wage earner.

***

From the heavy weight of the dictatorship and from the ceaseless fury of the class war, Carmen would be more fortunate than the two brothers. That political violence he did not really forget, but still sometimes spared him. Full of grace in demeanor, prudent woman, wise and careful with others, very sweet and communicative, long-suffering and dedicated to work, above the ferocity of the ideology of the time would be restrained. His father’s tribe also made “releases”.

Her two brothers had two names, one Italian and the other Albanian. This was an understanding since the couple came from Italy. Encio was also called Leonidha, Guido was also called Andon. Carmen’s mother had given her the middle name Marie, but surprisingly it was never used by either her parents or the Xhimitiku tribe. They never even found out that the little girl, “of old age”, born fourteen years after the youngest brother, had a second name. They left it with Karma. They learned to call him that. It was called as an Albanian name.

In her life, she went from being a temporary, “substitute” saleswoman in a food company, to becoming “permanent” for a few years. Then they treated it better, as inventory. When the new wave of the class war arose, in order to protect her, the lovers of the mother, the midwife who had been precious in the birth of thousands of children, moved her to the workhouse for just a few months. Then they would return it to the position before the strike, at least selling. Everything changed in 1985, when after the death of Enver Hoxha, there were actually signs of softening.

They fired her as a saleswoman and sent her to the outskirts of the city as a packaging worker. He had to take sugar or rice and flour from a big sack and put them in one-kilogram paper bags. The rate was 1021 in eight hours. In the first weeks he could barely do half of them and little by little something more. The friends of that arduous work, stronger and more trained, helped him every day.

When he returned home, in order to meet as few people and their gaze as possible, he walked through a second street of the city. However, among those who were afraid to have a conversation with him, it once happened that one of the managers of an important office in her company stopped him and “removed the warning”: “When you exchange words with me on the street, don’t lower your eyes, but raise them to greet you.”

It was 1952 and oil extraction in Kuçovo, which for a year was known by the new name “Stalin City”, was stopped. The engine of the TEC was burnt. In Vlora, the cisterns coming from the “socialist camp” were waiting in line. The device was Italian, and after two weeks of fruitless efforts by Czech and Russian specialists, it was realized that the only hope was someone learned from the previous engineer, Marineli.

This specialist was known to the leaders of oil extraction: Guido Xhimitiku. In 1948, when Marineli asked to be repatriated, the communist authorities made it a condition to prepare and leave a deputy. Among the young people who worked at TEC, he chose the son of compatriot Roza.

Endlessly she begged him not to put that heavy burden on his nineteen-year-old son, but the other did not back down from his decision. Guido was quite talented. So one day he took under his technical responsibility the complicated machinery. Then it happened that they put him in prison, accusing him of listening to the “Voice of America”, carrying out agitation and propaganda and attempting to overthrow the popular government.

At the beginning of the third week of the oil extraction blockade, Mehmet Shehu himself came to the city. As soon as they told him that there was a possibility to fix the engine, but the person was in prison, he ordered to bring him before him. “You wanted to overthrow popular power”? he gritted his teeth as soon as Guido appeared in front of him. He was ready to justify himself, but the Prime Minister rushed at him: “If I didn’t hang you on the triangle that I will put at the entrance of the TEC, don’t scold me Mehmet Shehu! How much have they punished you”? The young man answered with a mouthful, but the other cut him off: “You have to cooperate! Go see and fix the engine! I don’t leave here without putting him to work. How long do you want”? Guido pronounced “almost three weeks”, but the Prime Minister became even more nervous:

“Faster”! “Yes, at least ten days.” “Faster”! Shouted Mehmet Shehu. “A week”. “Faster, faster and now run to TEC”! It was the last call. With a policeman at his head, who was kindly chosen to be friendly, Guido fixed the serious defect in three sleepless days. When they brought the money back to him, Mehmet Shehu pronounced: “Now you are free, but what I am telling you will come to you officially. From now on you will work for the economy of socialism. For any problem or work problem, you will come straight to me”!

The release order arrived very quickly and after that Guido was mobilized as a soldier. Then he worked in the vehicle park of Ura Vajgurore and from there in the Ministry of Industry and Mines. Until he retired, he made many inventions, some, like ‘G 84’, made famous in the press of the time. It was a miner’s helmet device with an overhead light. Until then they were bought in Poland.

Guido was also decorated.

After prison, Encio worked in the Bulqiza mine. He too was a consummate technician, innovator and inventor as well. He became a fan of its well-known director, Teodor Bozo. When he left for another task and immediately due to the incompetence of the new leader, the implementation of the plan began to falter and later turned into a problem for the entire state, he was arrested. He was fifty-two years old. It was January 1, 1985.

Those who were responsible for this state of ruin of the mine that extracted currency for the empty budget coffers, among them a minister, a member of the Political Bureau, to escape from any punishment, used the old weapon of the Party: they invented the saboteur, the enemy.

This could only be Encios, well technician, once imprisoned for politics, with his father as well…! People of the State Security secretly made an explosion in one of the underground wells with dynamite and blamed the “technical error” on the predetermined victim.

Since this was very little and the arrested person did not accept it, he was accused of being an agent of the Italians, the Russians, the Yugoslavs… Because Encio resisted in order not to accept what he not only did not do, but did not even think about, the investigation lasted a full 19 months. Almost every day a masked man entered the room where he was being interrogated and beat him savagely. They even put him alive in a coffin.

During the cold winter of Peshkopia, where they kept him isolated, they left him with only a flannel shirt on his body. He was blinded in one eye. His heart weakened and began to suffer from arrhythmia more and more often. A living unburied person died. Then he couldn’t take it anymore and decided to commit suicide. Tried several times. Could not. They had taken away every means of doing it. Then sign what they wanted.

He was sentenced to 22 years in prison. In Spaç first, where he once had to make room for Mehmet Shehu’s son to sleep next to him. Then they took him to Saranda. Here the town with the prison was called “Progress”. Before the dictatorship, the real name was Saint Vasili. It was released in April 1991, among the last. He could not meet his mother. Roza passed away on February twenty-first. She had recently come to Laprakë in Tirana, where some simple apartments were given to those persecuted by the communist regime.

Encio’s heart rested the day he visited the future krushku, where he was betrothed to the boy. It was September 30, 1991. He had chosen him from Bulqiza, the city he had devoted his whole life to. He was buried on the outskirts of the capital, in a place called Sharre.

When the Italian occupation troops entered Berat on April 8, 1939, Roza instinctively raised her hand to greet them. He had compatriots and was tormented by longing for the homeland. But when she turned her head to her husband for a moment, she saw that he had tears in his eyes. He immediately lowered his palm. Out of shame, he hid his guilty hand behind his back.

In their house, the photo that Milto was most fond of was the one from November 28, 1922. It had been taken in Naples, together with his friends. It was in the first year of the university as a financier and in those days, in honor of Flag Day, they had established the patriotic society “Naim Frashëri”.

The conversation to return and settle in the mother’s birthplace was carried out when Roza was still alive. She said that she really wanted to go to her hometown and meet her people. With anyone who was still alive after half a century. But he couldn’t. He died on February 27.

At the beginning of March, representatives of the 96 Italian families remaining in Albania and their over 1,800 members were called to the temporary base of the “Pelikan” humanitarian operation, formerly the Pioneer Camp in Durrës. They met with the Minister of Foreign Affairs, De Mikelis, Minister of Labor, Marteli, and Minister of Immigration, Boniver. They were told that in Brussels, the United Europe had decided to repatriate them. They would not take any booty with them, but only a suitcase with their body clothes. In Italy they would find almost all of them.

This escape happened after six months. Guido was with them. When they talked with him about the fall of the dictatorship, he was adamant that he would not only run away, but also never come to Albania again. He settled in Peruxha, but very soon, every time he wrote a letter, he said that the Gorica Bridge in Berat was the most beautiful in the world. So he could not keep the oath.

He has been coming for quite some time a year, although quite ill with Parkinson’s. The son even bought a house for himself and for him in the “Don Bosco” neighborhood. Encio after leaving prison, after visiting his hometown, the city of one above one window, very eager to cross the sea and get to know his mother’s homeland, suffered a fatal heart attack.

That day when they talked about whether they would choose Italy or Albania to live, Karmeni said that she did not feel so enthusiastic about leaving. “I will go, but I will return”, he said. Later she became an Italian citizen, but she never wavered from her decision. Together with Dhimitri, they live in Tirana and cross the border only when they visit their three daughters and four grandchildren. Bruna is in the Italian city of Beluno, Fabiana in Bucharest, and Averisi in London.

In Sharre, the grave of their parents has photos of both of them. Roza, when Carmen and Guido, as well as the grandchildren, come to sit next to them from every position they approach, she seems to follow them with her eyes. And the wise Milto, continues to smile at them, always as if he is going to tell them something joyful. But under the marble there is still only pair of bones. Memorie.al