By Shkëlqim ABAZI

Part forty-four

S P A Ç

The Grave of the Living

Tirana, 2018

(My memories and those of others)

Memorie.al /Now in my old age, I feel obliged to tell my truth, just as I lived it. To speak of the modest men, who never boasted of their deeds and of others whose mouths the regime sealed, burying them in nameless pits? In no case do I presume to usurp the monopoly on truth or claim the laurels for an event where I was accidentally present, even though I desperately tried to help my friends, who tactfully and kindly deterred me: “Brother, open your eyes… don’t get involved… you only have two months and a little more left!” A worry that clung to me like an amulet, from the morning of May 21, 22, and 23, 1974, and even followed me in the months after, until I was released. Nevertheless, everything I saw and heard during those three days; I would not want to take to the grave.

Continued from the previous issue

II

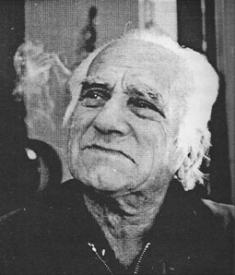

He loved the feminine uncontrollably, he adored beauty with the frenzy of a madman, and he desired freedom like a slave’s dream! Where the majority vegetated in routine, he felt the shivers and the pulse of life, the chirping of angels, the sensual finesse, the alluring whispers, the babbling of infants, the rhythmic musicality, the joyous clang, the fluttering delight, everything a slave wishes for to feel free.

His Muse frolicked, rejoiced, fluttered; her echoes did not cease even in the cell, but just like Orpheus, he mesmerized the nine sisters and sucked the nectar from their lips! Everywhere the moment caught him, he sang of life like a prince, of joy like an Epicurean, of suffering like a Shakespearean, and he clad the divine woman in superlatives, like a passionate lover! He bowed before the beautiful sex and made curtsies to the miserable woman who washed his worn-out shirt, or offered him a bowl of corn-mixed bulgur and unreserved love, after a day of wandering.

He despised the artificial and drove away the mischievous young ladies who glanced askance behind dark glasses. He caressed misery with royal verses; he praised the Roma man who, after the day’s haggling with mules and donkeys, would swig a few glasses of raki, get tipsy with the defi or qemanja, and start a wild party with the Romani woman under the light of stellar candles, defying all bosses with berets and sombreros. He would set off from the River Bank, strutting like a gentleman, because the miserable woman had cleaned his worn suit the night before, straightened the knot of his ancient German-era tie which he refused to exchange for any “designer rag,” and sent him off on his “mission.”

He would “park” his old cyclomotor in a “reserved” corner just for him, enter the “Kafe Europa,” and head to his “den,” where he would hide with his muses! He would settle in the “corner” and, while waiting for his coffee to be brought, he would set the sails of his mind. He hadn’t ordered for a long time, because the waiters, bartenders, and even the owner would welcome and greet him warmly, bring him his coffee and a pile of newspapers, and leave him to navigate his own ocean. He was so intimate with the environment that if he didn’t come one day, the staff would worry and ask what might have happened to their poet.

Yes, they considered him an exclusive poet! But Pano would compensate their gratitude well; the most accomplished poem, the last pearl he had scribbled on scraps of paper, on crumpled coupons, or torn pages of packages, even on the corners of paper napkins or newspapers, or whatever he could get his hands on, he would leave to them as a “tip.”

Over time, his benefactors recognized his taste. From time to time, they would bring him a glass of raki and two grilled meatballs along with his coffee cup, which he would pay for when he had money, but when he was broke, he would leave without settling the bill. But as soon as he got his hands on some money, he would return to his “shelter,” like a criminal to the scene of the crime, and like a noble bohemian, he would settle the “debt,” accompanying it with an excess, which he called the “glass’s honorarium.” When my path led me to the Capital, I knew where to find him. But I wouldn’t set off without securing Pano’s aqua di vita, or “medicine,” as he affectionately called the Skrapar raki.

I would stop at the “den,” leave the bottle, and leave without disturbing his meditations, because he was riding “Pegasus” and ignoring his surroundings. But when the light refracted on the crystal and hurt his eyes, he would descend from the ether; after sheltering the “medicine,” he would remember me and act surprised: “Wo-o-w, you here”?!

“Just arrived!” – I would reply, even if I had been there for an hour. – “Since I was passing by, I thought we’d meet, and then I’ll see to my business!”

“See to your troubles and leave the wreck to enjoy his own field!” – he would reply with a smile and caress the bottle like an infant. Sometimes I wouldn’t find him in his “den.” The waiters would give me information as if he were a relative; I would leave the “medicine” with the absolute guarantee that they would hand it over to the “patient,” and then I would see to my work. When I returned and found him folded over scraps of paper, I would greet him from the door:

“Pano, my boy, good to find you well, how are you doing, long may you live”?! – we would caress him this way, because he didn’t accept that he was getting old; perhaps in spirit, he felt younger than many youths aged before their time. This quirk originated in the seventies, when Shyqyri Gruda used to joke: “Everyone is a poet for a moment in youth, age demands it, but Pano, my boy, will remain one even in old age!” Shyqi had been right, Pano, over eighty years old, still versified with the passion of a twenty-year-old!

I would wait for him to dismount “Pegasus” and then head towards the “corner.” He would rise halfway, stretch his back, and reply cheerfully, with the stoicism imprinted on his charming face: “As God wills, my dear boy, come on, we missed you! At least I feel like the freest of the self-imprisoned free” – and we would embrace affectionately. I knew his quirks and his concept of freedom since prison, his adoration for nature, for flowers, for birds, for the wind, for the storm, for the air, for perfume…, for every authentic phenomenon.

Even though he belonged to the principled type, Pano Taçi hated false ethics, scorned strict rule, despised hypothetical pretenders who sought to show off to the world. He had controversial ideas about the artificial, he considered frameworks handcuffs, prison, isolation, evolutionary deformation. He even called anyone who tried to adhere to these rules point by point a “prisoner of morality,” just as he regarded the ocean:

“The ocean, slave of the earth, throws waves crosswise on its head / It boils, gasps, and moans, withdraws and trembles / It shakes off chains and stirs waves, it wants to overflow the shores. / When it rages and makes a commotion, it throws even its mother out of the bed / It raises its crests more and more, / flooding the land with salt and foam / It is ready to bind the Titans…/ As soon as it opens its tables, its sides are torn!”

He liked the galaxy and admired the stars when they shifted in the boundless firmament; he wanted freedom in his own way, with a platonic-earthly love, ethereal and sensory, fluid and tangible. Although they forced him to live amidst violent misery, he experienced freedom even behind bars, in the cells of Burrel or Spaç, in internment camps, or wherever the ignoramuses placed him.

While we suffered physical isolation, he enjoyed the fruits of passion, conversing with the wind, the rain, the snow, the rainbow’s multicolored tail, the moon’s horn, the sun’s ray, the swallow of Burrel. “I talk to spirits!” – he would boast when sadness overcame us and we felt on the verge of madness.

“Exactly who with?” – I asked him once.

“I had an amazing conversation with Sappho!” – he puffed up.

“Normal, it’s possible for you since you know Greek!” – I burst out laughing.

“No, friend, I didn’t speak Greek, but Albanian!”

“Since when has Sappho learned our language?” – I teased him further.

“That’s the language she has always spoken!” – he cut me off seriously.

“Forget it,” I said, “Pano is Pano, he talks with Homer, Aristotle, Socrates, Pluto, Pliny, Ovid, Petrarch, Dante, Shakespeare, Racine, Molière, Goethe, Schiller, Pushkin, Heine, Petőfi, Gogol, etc., etc. Come on, please, how can one take it seriously!?” and I didn’t pursue it.

Pano was not only the hallucinating poet who reveled with muses, but also an erudite of the highest order. When some linguists were debating with Vasil Dhimitriadhis and the other Greek, Janin, about the antiquity of languages and the autochthony of the region’s tribes, Pano supportively and vehemently backed Qani Çollaku: “Right, professor! Albanian is ancient, older than Greek, definitely, but even older than Phoenician!”

Vasil Dhimitriadhis’ Hellenic pride was touched: “I’ve long known your xenophobia, Pano, especially against Greeks, but I invite you to accept a priori that Greek has been and remains the mother of ancient and modern languages, the protophony of world culture, I hope you won’t contradict me on this point.”

When he noticed the irony in his interlocutor’s eyes, he added: “Of course, you might dispose of pseudo-arguments to divorce and cast aside this deduction, but I dare to tell you honestly what the civilized world has accepted without hesitation…!”

“Slowly, slowly qirje Vasilis, signomi (excuse me)!” – Taçi interrupted him in Greek, then in Albanian: “Megalomania in science is not an argument, but Hellenic stubbornness and fruitless boasting have blinded you Greeks, to the point of denying historical truths. Undoubtedly, ancient Greece made contributions to the dynamic developments of the ancient world, to the flourishing of art, culture, sculpture, poetry, tragedy, comedy, politics, philosophy, history, medicine; its merits in the field of legislation, in the application of civic democracy, in the debates of the agora as a precursor to parliamentarianism, cannot be denied. Naturally, at times it also practiced despotism and extreme tyranny, etc., etc., but this doesn’t mean that the linguistic base was necessarily Greek.”

“According to you, Homer, Socrates, Plato, Demosthenes, Lycurgus, Aristophanes, Aristotle, Sappho, Sophocles, Herodotus, Heraclitus, Hippocrates, Phidias, and dozens of others, spoke Albanian!?” – Dhimitriadhis became irritated.

“Naturally, I didn’t say they spoke exactly Albanian, but I insist that the basis of the languages was Albanian, more precisely Pelasgian. Of course, this is not my deduction; distinguished scholars, linguists, and Albanologists accept it, even Hellenists who have conducted in-depth studies.”

“I am hearing this argument for the first time today!” – Dhimitriadhis interrupted him again.

“Be patient, please, and listen to me until the end. You can object after I present the scientific arguments I possess, but not with the stubbornness of Achilles and the cunning of Odysseus!”

And he presented his ideas with erudition to envy even the most capable lexicographers and historians.

III

At the turn of the two thousands, the bookseller in my town, Avdyl Pilafi, gave me a poetic volume and suggested I read it. The book was neither thick nor luxurious, published on paper without any quality, while the cover featured a futuristic nude, with her arms crossed over her drawn-up knees, and an unheard-of name, Burgim Pata (Prisoner Pata).

I opened it randomly where my hand stopped and read an untitled poem with pronounced erotic content. I closed it and returned it, but he suggested I read it and guess if I could, who the author was:

“You can speak only after you have finished it.”

“It didn’t seem appropriate to me!”

“Read it, maybe you’ll change your mind! After all, we are mature, taboo topics don’t affect us,” – he scratched out an ironic smile that prompted me to take it again.

I finished it within the hour. The inappropriate theme with expressive language pushed me to find a piece of spongy pencil and circle a red stamp.

“What are you writing?” – Avdyli asked.

“I put a mark on it, warning the youth to stay away from this infected author!”

“Ha-ha-ha! I thought you wrote the name!”

“It has a name, even though it’s a pseudonym, but the content is not suitable for every age!”

“Tell me, who might the author be?” – Again with the devilish smile. – “If you have an idea, tell me privately, so others don’t hear!” – he added conspiratorially.

While we exchanged these replicas, many literature lovers, especially poetry, were leafing through the other copies of this mini-volume.

“When you finish, you will state your opinion on the author and the content,” Avdyli asked the readers and turned to me:

“I’ll start with you, since you finished it!”

“Pano Taçi,” – I whispered in his ear.

“Don’t speak until the others have expressed themselves!” – he froze and winked at me.

Naturally, I kept silent, but subconsciously, I repeated my friend’s name, even though the contrived pseudonym “Burgim Pata” (Prisoner Pata) seemed to wink at me: “I am the author.” Based on the linguistic style and literary figures, Pano’s invisible portrait was signaling to me.

“Reveal yourself, Pano, you don’t have to hide from us old friends behind any pseudonym, even a bombastic and resounding one like ‘Burgim Pata.’ We detect the poetic magic in the air, the subtle expression, the elegant language, which no one mastered except our stork, the delicate perfume of your word – we have smelled it in dozens of original creations, perhaps not of this genre and”… I pondered, while the past returned me to prison with the poet.

Awaiting the verdict of the chief surveyor (I want to emphasize that they set a symbolic honorarium: one glass of raki and two meatballs, a trophy that summarized Pano’s ambition and made him happy!).

As soon as the honorarium was mentioned, I classified myself as the winner. “I am victorious!”

“The author of this volume is Pano Taçi!” – Avdyli declared solemnly and turned to me with the “Taçi menu.” – “First, I wanted to clear up a doubt, did you know about this volume?”

“No! In the last meeting, he didn’t mention such a project! In fact, Pano never revealed to us verses of this genre, because with us, Pano maintains ethics!” – I explained.

“Then how did you guess?”

“Quite naturally! Any prisoner would have recognized this style immediately. Only our Pano writes with such finesse, such passion, and such elegance. You cannot find a second one like him!” – I concluded.

After the nineties, he published several poetic volumes with writings from different times. But it was not easy for him to find them all; a part faded in the recesses of the prison.

He started with “Blerim i thinjur” (Gray Blossom) in the early ’90s, continued with “Dhe vdekja do paguar” (And Death Must Be Paid) in ’94, with “Sa pak diell” (How Little Sun) in ’96, concluding a few years ago with the lyrical and libertine, almost pornographic, collection “Lakuriq” (Naked).

This last one, although quite controversial, Pano put his name and surname on, because he remained irreproachable, an eternal bohemian, an unparalleled lyricist, so he was allowed to overstep the mark, because he knew how to do it with perfect elegance, because he was the last stork. If someone else had dared to attempt this harmful experiment, we, the Puritan fellow-sufferers, would have been the first to attack them.

But Pano was Pano, and as such, he enjoyed the status of the incorrigible bohemian, whose lyricism knew no boundary, and we all had tasted a little of it, even amidst the barbed wires or wherever else he breathed.

In fact, even in the dungeons of Burrel, with a pencil tip that his friend Haki Gaba supposedly “forgot” in the bathroom, he had written a poem of this genre on the wall. His fellow-cellmate, the nudist painter Raqka, inspired by those verses, had embodied the inspiration in art; he illustrated the quatrain with the figure of a voluptuous nude woman, eyes set on the celestial or oceanic blue, beautiful and divine like the ancient hetaerae. “Fascinating, it lacks wings to suggest that an angel visited us!” – Pano expressed his astonishment.

“These divine verses deserve this angelic beauty,” – Raqka replied, and they spent the whole day with similar banter. They argued back and forth about the name; one called her Artemis, the other Helen, the first Aphrodite, the second Cleopatra; Pano finally named her Sappho.

While talking, the guard caught them. When the policeman came to take them out, his eyes fell on the drawing; in the lack of light, he approached to examine it closely. When he spotted the figure of the lustful woman, he began to howl:

“Immoral, scoundrels, panderers, vagabonds, rascals!” – Everything that came to his mouth. Pano listened patiently; when he was convinced the officer had nothing more to add, he turned to him: “Mr. Asllan, do you have children?”

“Yes, but they are decent, not rascals like you!” – the policeman replied with his eyes still on the wall.

“Very good, with whom did you make them?”

“With my wife, man!”

“Meaning, the female gave birth to them, not the male?”

“Phooey, whoremonger! Why, do males give birth?! Or do you mistake me for your buddy?”

“I know, if you were like that, you would be with me…”!

“Insolent! Enemy! Bastard-son!” – the policeman insulted him.

“Thank you for the high regard, but I wanted to ask you, why do you hate women?”

“They are whores, man!”

“Which ones?”

“This woman, look how she is, naked?” – Captain Asllani pointed at the drawing with his finger.

“She is lying on a bed, sir!” – Pano defended himself.

“Is that how women sleep, huh?” – the policeman said ironically.

“Why, does your wife lie down in bed with all her bloomers on?” – Raqka retorted.

“Shut up, you rascals, vagabonds, scoundrels…”! – the policeman vented and locked the bolt.

But as soon as he met his colleagues, he told them what he had seen, and all the internal guards came one by one, pouring out a torrent of insults: “Immoral, scoundrels, panderers, vagabonds, and rascals,” but they did not touch the drawing; they looked at it with curiosity and told others, who did the same.

The curiosity reached the ears of the prison commander, Nazar Demiraj, who took the trouble to visit the two broken artists as if coincidentally. After feasting his eyes on the moss on the walls, Nazar focused on the drawing:

“What is this naked piece of vegetation you have here, boys?” – he feigned surprise.

“The ancient Sappho has blessed us, Commander!” – Pano replied.

“This little Sappho of yours doesn’t look that old to me!” – he started to comment and stretched his neck to see more clearly.

“She is from ancient Greece, Commander!” – Pano interjected again.

“Ah, so she’s Greek? Well done for putting her in the dungeon; after all, monarcho-fascists belong here, since you are enemies on both sides!”

He did not increase the artists’ punishment but gave the order to whitewash the cell walls with plaster and lime. Naturally, Sappho disappeared, but the walls were whitened, having been last painted ages ago.

IV

Pano’s life was full of extremes. In his youth, he was an unconscious bohemian.

After a reserved childhood, he plunged into the vortex of war following wealth; then schooling and subsequently the poetic whim pushed him towards the “forbidden apple.” And finally, he ended up as an “enemy of the Party and the People.” In prison, he was again a forced bohemian, but he found solace; at least he could freely vent what boiled in his soul. When he completed his sentence, they temporarily released him, but he chose the bohemian life himself because it suited his temperament, as the most appropriate way to enjoy freedom.

Nevertheless, the punishment continued; without a family, without friends, without belongings, without work or a home, penniless, he wandered wherever his fancy took him, eating wherever he found food, sleeping wherever he collapsed.

Despite the deprivations, he remained a knight of beauty. For this period, Jorgo Bllaci, his friend, who was also a poet, recounted:

“All poets belong to the species of the incorrigible loner, the reserved wealthy man, and the convict of every epoch, hence they remain eternal bohemians! But Pano surpassed us all, because he despised boundary markers, rules, hypocrisy, falseness; he liked love without frames, freedom without limits, beauty without form. His motto: ‘Better poor, among free people, than rich, surrounded by gold and chains!’ was the leitmotif of that time.”

Thus, what Pano liked, the regime could not stand; what the regime demanded, Pano did not implement, and a paradoxical duality arose, as if a kind of dragon with two heads; on one side, the freedom of the dreamy poet, on the other, the “gift” of the refractory state. But the state’s “gift” was summarized in a package of coercive obligations, exactly what he hated the most, and the rift deepened, God forbid! The poet played with freedom, the state with handcuffs…!

Naturally, the state possessed the machinery of violence, while the poet only owned the flute of Orpheus. Thus, they convicted him a second time, and again and again, until the day of democracy arrived. But when it came, the Poet was tired, like a nightingale that runs out of energy from singing day and night, for a long time. Nevertheless, he gathered his last strength and continued the apotheosis:

“If you want to arrive first, run alone; if you want to go far, run in a group.” And alone, he ran faster than everyone and arrived further than he could have gone with others. In the end, he fell silent… and took flight to Eden, where the young and ancient poets awaited him.

V

He was broke, with a minimal pension, because he couldn’t complete the required years of state work. Meanwhile, he hoped they would process the second installment of his many years in prison, so he could spend it with his benefactors; drink with the Roma people; he especially regretted not having a souvenir for the poor woman who served him daily. Meanwhile, he also waited to publish his complete work, at least to feast his eyes on the creation for which he sacrificed his life, because everyone abandoned him, to the point where he couldn’t even recognize his biological child!

The state, as the state, ignored him, and no one remembered that a certain Pano Taçi, poet, existed…! His prison friends, scattered everywhere, still remembered, were proud, and boasted about their poet. Surprisingly, even the statesmen finally remembered! After letting him starve to death while alive, they organized posthumous tributes; while his prison friends supported him, stood by him, and subsidized the publication of his work…!

VI

“I was born at the white dawn, of the pitch-black time / amidst the darkness, I sought good fortune in the hell-prison / and I await a white death… after midnight / to rest peacefully, beneath the softness of the goose quill!” He was born poor, lived poor, but died rich! Naturally, rich in images, in dreams, and in illusions of beauty…! Memorie.al