By Qerim Lita

Part One

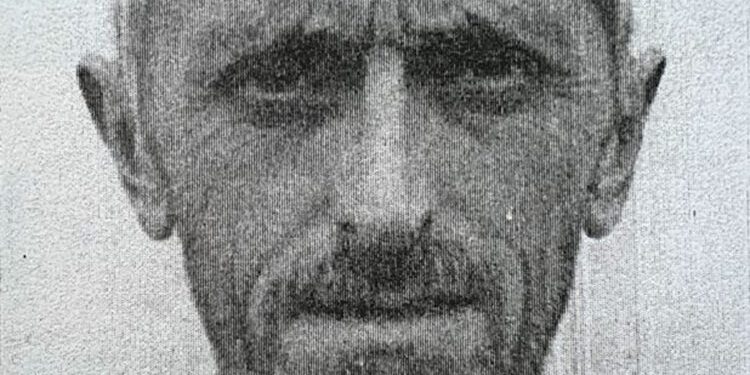

– Ukë Cami, Distinguished Albanian Military Figure and Nationalist –

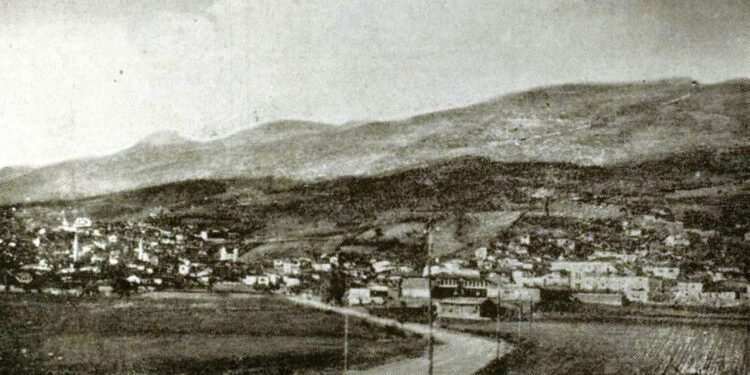

Memorie.al / Ukë Ramadan Cami were born in 1896 in Sepetovë, a neighborhood of Tërbaç, in the Ostren Municipality of Dibra. His home, located near the crossroads leading to Struga, Dibra, Golloborda, and the lesser and Greater Gryka, was always open to the leaders and patriots of the national movement. His father, Ramadan, was a determined fighter for the constitution and among the first activists to form the “Bashkimi” (Unity) club of Dibra. As an activist of the club, supported also by Eqerem Cami, he conducted intense propaganda activities in both the city and the highlands.

The Camis are a large family, part of the Dibra nobility, spread across the villages of Gjorica, Viçisht, Golovisht, Sepetovë, and Greater Dibra. During the 1920s-1930s, this family numbered around 60-70 houses. The early origin of the Cami clan is thought to be the Camaj clan of Dukagjin. Due to blood feuds, the ancestors of the Camis migrated to Lami i Madh, Selitë of Mati (Mirditë), where traces and properties such as “Cami’s Field,” “Cami’s Pear Tree,” and “Cami’s Meadow” still exist today.

Ukë Cami himself, after returning from Dukagjin where he participated in suppressing the Dukagjin uprising (1926), recounted: “I met elderly men of the great Cami clan in Dukagjin. In conversations with them, they spoke of early movements of their ancestors toward Shkodër, Lezhë, and Mirditë. Their accounts matched those of my grandfathers, although the latter could not trace their origin further back than Mirditë.”

The Early Years and Resistance

Ramadan Cami, with citizens and villagers from Gryka e Vogël and Golloborda, had formed a volunteer band of over 50 men. He maintained ties with Albanian leaders and patriots from the Dibra region and beyond, becoming a very important figure in the area on the eve of independence.

With the outbreak of the Balkan War, Dan Cami, along with his volunteer band, fought alongside Mersim Dema and other Albanian patriotic forces in Florina and Manastir. Meanwhile, from December 26, 1912, to January 7, 1913, he organized a determined resistance against the Serbian occupiers near the Spile Bridge. Through treachery, the Serbs crossed the Spile Bridge and, in an act of revenge, burned his house; the family took refuge in Lukan for six months. It was in this spirit that his son, Ukja, was raised and inspired. At the age of 17, he joined his father’s band in the September Uprising of 1913 against the Serbian occupiers, which, as is known, broke out precisely in Dibra. From that moment, Ukja would never leave his father’s side, actively participating in the anti-Serbian wars of 1915, 1918, 1920, and 1921, as well as the anti-Bulgarian war of 1916.

Following the outbreak of the Dukagjin uprising (November 20, 1926), organized by the circles of the then-Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), Ahmet Zogu invited the leaders of Northern and Northeastern Albania to join the Albanian army and gendarmerie in quenching the rebellion. Such an invitation reached Dan Cami, who, after assessing the situation, sent his son, Ukë, as the leader of a volunteer force consisting mainly of the Cami family, friends, and supporters.

This was a heavy and responsible task for him, as it was the first time he would lead a volunteer force. However, as the Albanian scholar Gafur Zota writes, Ukja, at the head of that volunteer force, “showed courage and bravery in suppressing the uprising” in Shala. He remained there for nearly six months until the situation was fully normalized, returning to Sepetovë having expressed full support for the Albanian Government and Ahmet Zogu.

Alignment with National Policy

With the redefinition of the Albanian State from a Republic to a Monarchy and the proclamation of Ahmet Zogu as “King of the Albanians” rather than “King of Albania” (September 1, 1928), signals were sent that King Zog I and the Royal Government would express a significantly greater interest in the Albanian problem under Yugoslav occupation. Within this political shift, in 1930, the Royal Government allowed the settlement of the leaders of the Committee for the “Defense of Kosovo” in Albania, such as Bedri Pejani and Ibrahim Jakova.

Rauf Fico, the Albanian Minister Plenipotentiary in Belgrade, informed King Zog in 1929 about the dire position of the Albanian population due to the terror of the Belgrade regime: “Yugoslavia… driven by the hatred it feels in its soul against the Albanian race… has done everything in its power to disappear and exterminate the Albanians.” He proposed that Albania raise its voice for its ethnic existence and demand the opening of Albanian schools in Kosovo and Macedonia.

Naturally, this positive turn reinforced the loyalty of Dan and his son, Ukë, to King Zog, in whom they saw the symbol of national unity – the only authority that could guarantee peace and the future of Albania.

The Death of Dan Cami

On April 19, 1933, after a short illness, Dan Cami died. His authority was evident during the funeral ceremony, attended by a large number of leaders not only from the Dibra region but also from Luma, Mati, Has, Tropoja, Mirditë, and more. The newspaper “Besa” (April 26, 1933) covered his passing under the title: “The Death of a Patriot.”

After Dan’s death, Ukja continued his national path. He inherited not only wisdom and bravery but also friendships with major tribal leaders: the Demas of Homesh, the Agollis of Kërçisht, the Karahasans of Radovesh, the Ndreus of Sllova, the Kaloshis of Kandri, the Lites of Kalaja e Dodës, the Biçakus of Elbasan, and many others. He was assisted by his brothers, Ferit (a regional secretary in Gollobordë) and Rifat (an officer in the National Army).

In 1937, on the 25th anniversary of Independence, King Zog honored Ukë Cami with the rank of Captain for merits and loyalty to the fatherland.

Internment in Berat and WWII

Due to his anti-fascist stance, at the beginning of 1940, the Italians interned Ukë Cami and his cousin Sinan Cami in Berat. They remained there until late 1940 alongside other Dibra leaders like Sefedin Kaloshi and Demir Dema. Tefta Cami writes that the Italians raided the village of Viçisht in revenge for the area’s resistance, executing eight men from the Cami family.

Upon returning from internment, Ukja established links with nationalist leaders such as Fiqiri Dine, Muharrem Bajraktari, and Abaz Kupi. Following the collapse of Yugoslavia in April 1941, he participated in the Albanian Committee of Dibra. As Greater Dibra became a prefectural center, Ukja was appointed Regional Governor (Krahinar) of Golloborda, Zhupa, and Reka. By early 1942, he formed a volunteer band of 200 to 300 soldiers to maintain order and prevent the infiltration of Bulgarian komitadji and Yugoslav-Macedonian communist bands.

During a later investigation in 1945, Ukë Cami stated: “I did not have a good opinion of the partisan movement. When partisans appeared in the Highlands or Zhupa, I immediately mobilized the Albanian and Turkish villages to pursue them.”

The Committee for the Freedom of Ethnic Albania

In July 1943, the “Albanian Committee for the Freedom and Independence of Ethnic Albania” was formed in Greater Dibra, with Fiqiri Dine as chairman and Ukë Cami as a key leader. This was followed by the Assembly of Lura (August 27, 1943), where it was decided to enter into open war against the occupiers regardless of party affiliation.

While nationalists sought to unify the struggle, communist leaders like Haxhi Lleshi, directed by Yugoslav missionaries (Tempo, Popoviqi, and Mugosha), followed a policy of division. Despite this, a joint staff was briefly formed in August 1943. Nationalists insisted that the entire Dibra region, including Greater Dibra, be declared a free zone. With the insistence of the nationalists, partisan forces were forced to participate in the liberation of Dibra on September 8, 1943./Memorie.al