An editorial by Daniel Edwards on Diego Maradona

Memorie.al/ Saturday marks the 40th anniversary of the first triumph of Diego, winner of the World Cup for Youth, a triumph that was exploited by the infamous dictator of Argentina, Jorge Videla.

Before the young Argentine footballers traveled to Japan in August 1979, Diego Armando Maradona was just another promising young man hoping to put his name at the level of the world football elite. By the time that team came home with the World Cup in hand, the 18-year-old with curly hair was about to conquer the planet.

Even today, exactly 40 years later, Albiceleste’s fame for winning the Second World Cup, for Youngsters, retains the legendary status in Diego’s home country. For Maradona herself, this was a giant step in a career that would shock and exalt the masses almost worldwide.

The story actually begins a little over a year ago on the outskirts of Buenos Aires, by Jose C.Paz. When Maradona was just 17 years old, he was already boasting of two full seasons as a first team player with the Argentinos Juniors club and rumors of him being included in the national team for the 1978 World Cup to be held in Argentina., had reached its peak.

The coach, Cesar Luis Menotti, however, turned a deaf ear to those big calls, for Maradona’s participation in the national team. After winning a spot on El Flaco’s 25-man squad, Diego was informed at the AFA training base that due to lack of experience, up to that point, he would not be part of the final tournament. El Grafico journalist Carlos Ares was covering the team at Jose C. Paz and thus recalls the teenager’s despair when he was left out of the team.

“That day I stayed for dinner and when I left the base alone, it was dark, it was very cold, and I heard someone crying,” Ares recalls in the book Vivir en los Medios. “I saw the strongest image I can remember, it was Maradona, sitting by a tree, crying out loud. I clearly explained something to him, “You know how many World Cups you will play, right?” But he answered me crying, “How can I tell this fact to my father?” “He told me he would never forgive Menotti for that.”

“When I was left out of the list of 22 people because I was very young, I began to realize that anger was a fuel for me,” Diego himself wrote in his autobiography. Thankfully for the history of Argentine football, Maradona and Menotti were able to overcome that early hurdle in their relationship and when the World Cup winning coach took the reins of the youth team, 12 months later, Diego was the star. it’s great that would shine.

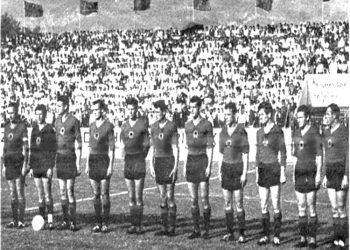

Qualifying for the World Cup was secured in January 1979, when Maradona’s team finished second to host Uruguay. A team inspired by their magic number 10, the future star of Internacional, Racing Club and Genoa, Ruben Paz.

Alongside Albiceleste’s “eagle” was Ramon Diaz, who played in Italian football. And later debuted as a player and coach for River Plate. Together this duo made a great striking force.

Menotti’s plans for Japan faced early and potentially serious setbacks. In 1979, Argentina remained in the clutches of a military dictatorship, which would later gain worldwide fame for the “disappearances” of its citizens and the “death flights”, where prisoners were drugged and thrown from planes, in Rio de la Plata.

Authorities continued to enforce compulsory military service, officially known as Colimba (a combination of Spanish initials symbolizing iron discipline). And exactly six members of the team, would be called up for service that year, as: Juan Simon, Juan Barbas, Gabriel Calderon, Sergio Garcia, Osvaldo Escudero and Maradonas himself.

At the end of April, the teenager Maradona, entered this service, which made him miss some Argentine games, not to mention the losses from not promoting his publicity brands. Two weeks later he gave an interview to Argentine state television: “I am very happy here because I have been treated well but I always try to respect the rules as much as I can. “I have the freedom to continue training and meet the national team.”

Thanks to their privileged status, however, not to mention the dictatorship’s “love” of using sporting success for its own purposes, the young Argentine stars were spared the hardships of military service. “I have never stood as a soldier, I have not touched a single weapon,” Juan Simon Clarin told Rosario’s military unit. Barbas added: “I would never achieve my best physical shape, thanks to excessive military training.” provided they return to duty after the tournament is over.

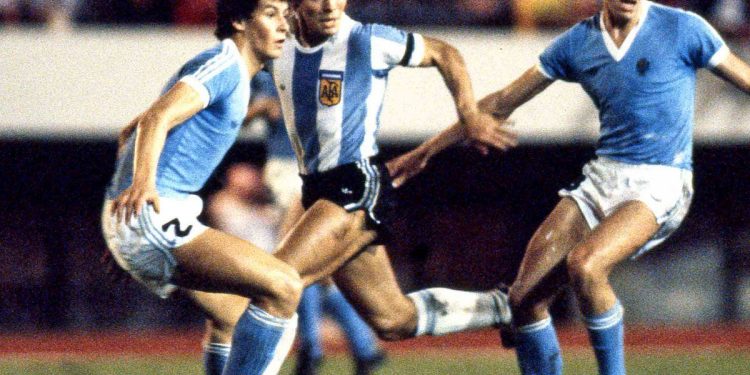

Argentina’s first test in Japan saw Albiceleste face off to begin football in Indonesia, who easily reached a deep 5-0 result. Diaz, scored a double, while Maradona, scored with two goals of his style. But they sweated a little more in the next meeting, during a tense clash against Yugoslavia. Match set by Escudero’s only goal.

First place in Group B, would be with a collision against heavyweights. Poland, which boasted a host of young talents who would continue to win the bronze medal at the World Cup, three years later in Spain and who had eliminated Yugoslavia and Indonesia without much fatigue. Maradona, however, took just seven minutes to destroy the Europeans, firing in a brilliant attempt, with his left foot from outside the area, to beat Jacek Kazimierski between the posts.

From there, then, a potentially complicated collision would be, much simpler. Calderon and Simon, were both targeted before the first half, with Andrzej Palasz also scoring for Poland. And after the break, Calderon scored in the second half of the game to seal a 4-1 victory, which was a warning for the rest of the race. The quarter-finals were just as straightforward, with Maradona opening the scoring again before Diaz scoring his second double at the World Cup after Algeria lost 5-0 to reserve a place in the last four.

Like their neighbors Rioplatense, Uruguay had also defeated Japan in the storm of its goal. Celeste’s won all four of their opening matches to advance to the semifinals. Paz scored three goals along the way, while goalkeeper Fernando Alves (a future Penarol legend and member of the 1986 and 1990 World Cup teams) remained unbeaten in conceding goals. The two sides of South America, now clashed in Tokyo, in a game that was expected to finally decide the winner of the competition.

This time it was Argentina that came out on top. Diaz scored early in the second half, with a clinical conclusion to Alves, before Maradona ended up with a tough counterattack heading home second to kill the race. Now only the Soviet Union stood in the way of the Albiceleste’s. And a second world title in as many years to come.

“Guys, you are already champions, I do not care about the result of this game, you have already shown that you are the best in the world. No foul or crazy stuff. Go out, play, and entertain the 35,000 Japanese in the stands. “With that, Menotti sent his new players on September 7, 1979, in front of a crowd of fans, who had taken over the capacity of Tokyo National Stadium, which was fascinated by the Argentine team in general and Maradona in particular, during the previous weeks. And they did not disappoint, their fans.

Despite the debut of legendary Igor Ponomarev, Argentina turned noisy. Hugo Alves, equalized 68 minutes later and Diaz finished the return a few moments later, but inevitably it was Maradona, the one who had to have the last word. Ten minutes from the time the Argentine “eagle” got up to shoot at an extraordinary free kick from the edge of the area to seal the score at 3-1, confirming his nation as world champion.

The festivities in Tokyo were short-lived. The dictatorship’s insistence on taking on the new team’s achievements marked a slightly bitter post-scenario of history. Upon returning to Buenos Aires, the Argentine team attended a public title party, along with the assassinating president, military man Jorge Rafael Videla. In a sudden turn, the ceremony coincided with a visit by the International Court of Human Rights, sent to Argentina, to investigate reports of disappearances and other serious violations of fundamental human rights. A fact opposed by a massive campaign declaring that the nation was de jure and de facto, “Man and the Right.”

Maradona and five of his Colimbas colleagues, meanwhile, were forced to resume national military service as soon as they returned to Argentine soil, including a meeting with the dictator himself at army headquarters. “Although we were the 1979 Youth World Cup champions, that bastard Videla used us as an example, “Maradona posted on Instagram in a 2017 post.” He made us cut our hair and do military service. And it happened to us that we brought the World Cup from Japan! “Over time we learned we were used to it,” Escudero added.

This forced celebration was especially heartbreaking for Jorge Piaggion, who had seen limited playing time in Japan. A relative of his was among those officially labeled ‘detained or missing’, and who were eliminated while performing military service in 1978. His disappearance remains enigmatic, even to this day.

“Imagine the celebrations in my city and how I was received. “It’s a big fuss because a world champion had arrived there,” he later said of his return to Argentina. “There I found out that my aunt had been in the square, with the protest group seeking information about the missing Madres (de la Plaza de Mayo) and that she had been attacked by the police. She was in Buenos Aires trying to find out where her son was.

“Returning from Japan was very strange. We celebrated in Japan and clearly got a call. ‘You must return’. I remember we came back in a hurry. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights was already there, but we did not know. We did not even know who they were. “We had all the innocence of this world.”

That triumph in 1979, had another, quite happy legacy. As the first major international tournament hosted in Japan, the World Cup sparked a new love of football in the country’s population, a phenomenon consolidated the following year when the Intercontinental Cup between European and South American champions moved to the Far East.

Superstars like Zico, Renato Gaucho, Ricardo Bochini, and most recently, Boca idols Juan Roman Riquelme, and Carlos Tevez, electrified Japanese fans, with Xeneize in particular gaining a cult spot in the country, thanks to their brilliant play in the decade of the first of the 21st century, which led to the defeat of Real Madrid and AC Milan. But it all started with Menotti. Maradona and that unforgettable young Argentine team that made them Albiceleste world champions at both the adult and youth levels.

Many of those players, as is inevitable, failed to make much of an impact on their professional careers, leaving Japan 1979 as the pinnacle of their football achievements. For Maradona, however, the best and most magical was coming./Memorie.al