Part Two

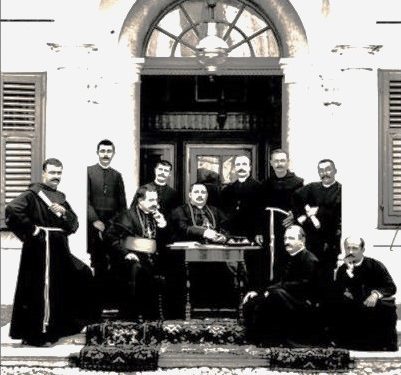

Memorie.al / To make the demands of the uprising of the Catholic tribes of Northern Albania known to the Great Powers, and subsequently to coordinate efforts with neighboring countries regarding the Albanian issue, the assembly entrusted Prend Doçi. This was the first attempt with a genuine diplomatic emphasis, which, although well-studied, unfortunately remained within the framework of an “impossible mission.” The journey of this mission began directly from the last assembly held in Breshtë of Orosh in early May of that year. With the aim of self-accrediting outside the territory of the Ottoman Empire, and then through Montenegro, Prend Doçi was to travel to Vienna, Rome, Paris, and London. The same itinerary, and roughly with the same purpose, would be followed 35 years later by the “Old Man of Vlora” (Ismail Qemali).

Continued from the previous issue

With swollen feet, to avoid the risk of potential paralysis, he moved with effort along the side wall of that “living grave” (prison cell) against which the sea waves crashed rhythmically. Their noise, though monotonous, brought the only hope of life…! Not infrequently did it seem to him that everything would end here… in this distant abyss… he remembered his compatriots, the Mirditors who mourned them as lost, and he felt pain… perhaps they had experienced it before him and could have been victims of this Ottoman invention.

Is there anything more tragic and unjust than these people reduced to this state for the sole fault of wanting to live free in their own land, refusing to endure the subjugation of the foreigner? The monstrous injustice of this whole situation kindled a deep, burning anger in his Christian soul. In that ill-fated environment where tomorrow could be different even for himself, the young Benedictine remained true to himself.

The pain, suffering, and emotions that accompanied the sudden tumble of events did not weaken his will; instead, they served as sparks of hope rather than premises of fatality. He was troubled by a sorrow of doubt locked in his soul that he wanted to release without malice. He tried to free himself from the anger caused by the disgusting memory of the “Arnaut” (Albanian) interrogator! He bore the shame for his misguided compatriot. Wrapped in him in the scant part of that isolated gloom.

While trying to doze off to consume some of the time that seemed to have stopped, suddenly Prend Doçi’s ear caught fragments of words in Albanian, barely emerging from the mouth of a being trembling with sorrow. Sounds of pain that resembled more a silent mourning of men, which he knew well. They formulated something indeterminate, turbid, swaying like something unbelievable between dream and delirium, life and death. The prison water-bearer, with great pain, conveyed the bitter news of the imminent execution of his compatriot.

Dom Prend Doçi – whom the water-bearer neither knew nor was aware he was in that prison. A piece of news that traversed all the cells that July night, shaking the minds and hearts of all the Albanians who were there. I do not know, dear reader, how you or I would act if we suddenly learned that in a few hours, we would fall prey to extreme, and most anti-human violence. The rope! He fell silent; he remembered the investigator. Cynically, he had warned him, even in the Albanian language. Fate willed that he hear the mandate again in Albanian from another Albanian. This times a very benevolent one.

A painful paradox that he faced with manhood. He troubled no one, complained to no one. He faced everything alone, with admirable bravery and intelligence. Without losing power over himself, such that he did not even show him to the water-bearer. He was one of those wonderful men the world calls “crazy” because “they do not fear death.” After prayers and beyond the meditations of that over-extended July night, something within him brought to his attention the spiritual strength and the limitless abilities of man as a being of the Almighty to overcome fear – this feeling strictly opposite to the life given by God.

He was only thirty-one years old, located somewhere midway between reality and anxiety. Undoubtedly he did not feel calm, but he was very conscious of understanding that this could be his last night. It was perhaps not the first time he had experienced such a feeling. Death, in his concept as a cleric, was a different notion. It was the will of the Creator. A divine category. Although painful and contrary to life, it was born together with man. He contested it as premature because he felt indebted to his own land, for which since his school days, he had poured the most beautiful feelings of his soul into verse.

The unexpected, that treacherous thing that plays with man, had exercised upon him that night one of those crushing shocks given sometimes by the imposed occupation of a tangled knot of thoughts, from which he was now freed. He felt calm, optimistic; he did not think that such a quick departure from life would be his lot. Facing death, which weakens you with its shadow, is also fate that sheds its own light. From here stemmed the tranquility, courage, and unparalleled optimism of this man at the dawn of that marked day.

Dawn, who in that human ugliness was distinguished only by the creaking of heavy doors eroded by moisture, the noise of irons, and the violent shouts of the internal guards, seemed to bring reconciliation in the soul of the young abbot. The weak refracted rays seemed to distort even more the sluggish movements of the silent silhouettes of the prisoners. A new day was beginning. Undoubtedly different, as he did not know what would happen. Far off, in that ominous half-darkness that had no end, the abbot spotted the water-bearer. Everything that night had focused on him.

Though a victim of an unknown lot, his secret held for Doçi something enigmatic, which fate for some reason had placed there. If not… at least for a messenger. Even that is not little, the abbot thought to himself. Fleetingly he remembered his mother… “May it be for his own sake…” she had once said! He waited until the water-bearer approached the bars of his partition. He greeted him in Albanian. After calmly telling him who he was, he urgently asked if he could secure paper and tools to write to a friend outside the prison. The water-bearer, shaken by Doçi’s fate and full of sorrow, told him on his return that outside the prison, only the Armenian could do something.

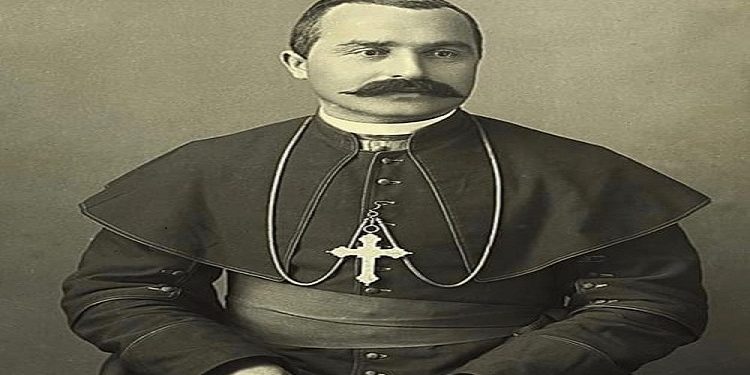

A handsome young man with a benevolent look who seemed to enjoy the sympathy of the prisoners. Under the armor of the instinct for survival, that very day Doçi approached the Armenian. The first glances they exchanged concerned the danger of which both were aware. Within a very limited time, with an enchanting and perfect ethical discourse, with marked notes of gratitude and loyalty, in elegant Italian, Doçi made it known that although facing death, he felt obliged to inform the nearest authority, the Catholic Primate of Istanbul, Msgr. Stefan Azarian, of his presence in that prison, hoping for his generous help.

Fate, which is usually always on the side of the brave, willed that this request, although very dangerous, touched the right spot in the soul of this cultured boy of the long-suffering Armenian people. As soon as the good Armenian turned his back – whose name was never known – Doçi felt what he had never experienced before. Something more than human, which exceeded the dimensions of simple help, pushing him magically toward an adventure. Inside him, a power began to grow, before which everything else turned into a duty. Into a weaving.

Thus, as soon as he passed the prison door, totally surprised by the thought that he had never imagined a human being could be so calm before death, speak so clearly and in such a captivating manner, he hurried impatiently to the Primate’s seat to fulfill what he had promised. On the way, as he hurried, the thought gripped him that his efforts might remain a bitter memory. He rejoiced in the Patriarch’s good name.

He worried whether he was on time. He prayed that that piece of paper would make His Grace experience what he himself felt facing that unknown prisoner. The greeting of a random passerby seemed to calm him. Fortuitous chance included here another Armenian, a priest in his thirties, for a mission higher than to free his compatriot from the bad nightmare of doubled thoughts that had possessed him.

He immediately showed him the letter and his urgent concern to meet His Grace, Patriarch Msgr. Azarian. The priest’s heart leaped when he saw the familiar handwriting and, totally surprised, he did not believe his eyes as he saw the well-known signature of his beloved colleague from the Urban University of Rome. Thus, the saving letter reached His Grace Azarian in time, from another Armenian. Who is believed to have graciously conveyed also the intellectual qualities and values of his fellow student of the Propaganda Fide.

The honored Patriarch, who was aware of the case of the Albanian prisoners but until then did not know that a Catholic priest was among them, immediately sent his secretary there, who also met with Prend Doçi. And after being informed about everything in an urgent audience with Sultan Abdul Hamid, thanks to the old friendship he had with him, he obtained the firman for his release from prison. Meanwhile, at the “Final Station,” hour after hour, the abbot waited for something to happen. Whatever it might be that would take him out of that inferno.

From that torturous state. To free him from sliding thoughts that swayed between two extremes. To save him from that macabre environment where he felt, at the same time, in two states – alive and dead – without knowing which he would face. Prend Doçi was released from the Istanbul prison in early July 1877. Throughout his life, the moments of the sudden meeting with his Armenian colleague waiting at the prison door, which would accompany him to the Patriarchate, would remain unforgettable.

In the impressive meeting with Msgr. Azarian, his savior, the abbot with a simple humility, completely within his nature, with an impressive ethic and a nimble language, would briefly and beautifully express his deep gratitude for everything they had done for him. Of course, he did not forget to heartily thank his Armenian compatriots whose humanism, sense of freedom, and the unalienable syntagma “faith-fatherland” made them disregard danger and everything else to save him.

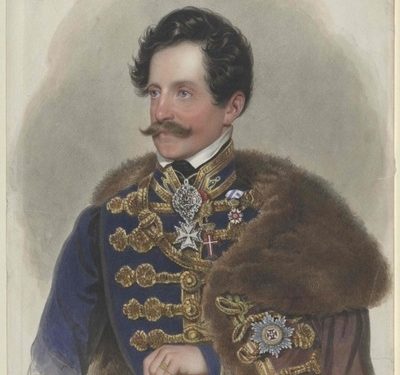

“You were lucky to write to me, son, before Dervish Pasha returned to Istanbul; otherwise it would have been difficult to save you. Therefore, it is necessary that you leave Istanbul as soon as possible. Because if the general finds you here, I fear they will give the order to imprison you again,” – the Primate replied with love. Thanks to the intervention of the Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Istanbul, Count Graf Zichy, and the care of the Armenian Primate of Istanbul, in July 1877, Prend Doçi left Istanbul for Rome.

Only two days later, when the priest Prend Doçi, dressed in the Benedictine habit under the name Pere Achile, was traveling somewhere in the waters of the Ionian or the Adriatic, Dervish Pasha arrived in Istanbul. As soon as he learned that Prend Doçi had been released from prison, he almost burst with rage. He left no stone unturned to convince the main authority that Prend Doçi was the main inspirer, organizer, and leader of the Mirdita uprising. Forcing him to correct his release firman, adding the extreme paragraph of expulsion from the territories of the Ottoman Empire.

From the abbot’s closest friends and collaborators, we learn that even in the final years of his life, in special moments of joy, he felt the need to speak to his well-wishers about the unforgettable impressions of those days and to express the most noble gratitude to all those who made his salvation possible. / Memorie.al

(Monograph for Abbot Prend Doçi)