By Idriz Lamaj

The third part

From the works of the apostles of ethnic Albania

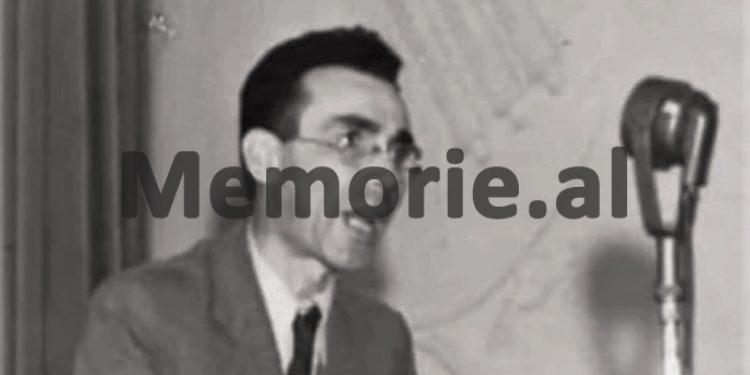

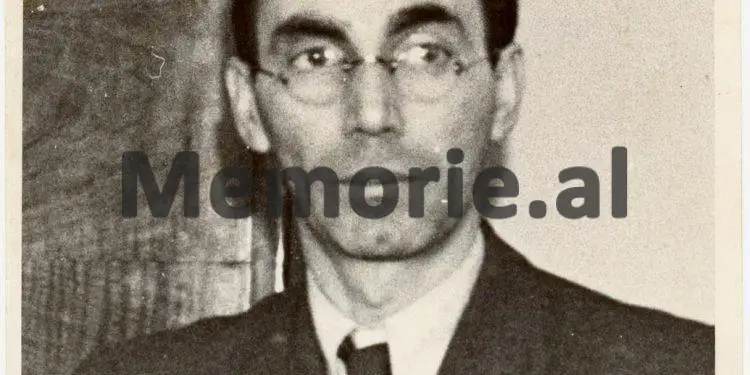

Xhafer Deva

In light of his own letters and other diaspora revelations

Preface

Memorie.al / Maybe like many others, I often browse letters with my friends and associates, who are no longer in this life. Browsing through them, for a moment unfolds memories that it seems to me that some of them can serve our history. Then, I return to the awareness of the current difficult situation in the ethnic homeland, caused by the quadruple of Albanian politics, I say to myself: “What can my memories of others or the letters of the people of dead?”

Without being the ominous instigator of pessimism, thinking as always of a better future, I return to my obligations to my friends, and as an icy observer of time, without any claim of historical service, when I am given the opportunity of publication, write what I have in mind, always based on their writings and letters. This principle is also followed in this book about Xhafer Deva. I knew Xhafer Deva in person; we exchanged visits and had a strong correspondence.

I spent days off at his house and inherited all of Xhafer Deva’s correspondence with Rexhep Krasniqi, his closest friend, for more than 40 years. After many years, I talked on the phone with Mrs. Deva’s daughter and son-in-law. In the conversation going on, taking advantage of the old friendship, I asked about his letters and they informed me that it was all Qefali Hamdia, a friend of their family.

In June of last year (2001) I went to Kenosha, Wisconsin, a guest of Qefali Hamdia, to look at Xhafer Deva’s correspondence, which Mrs. Deva sent her years ago, when she, due to her advanced age, was closed his house to go to the house of his 5th daughter and son-in-law, Mrs. Burgl Dagmar and Rev. Dennis Logie.

After reading the bulk of the letters, in the languages I knew, I took with me more than a thousand pages of his correspondence, covering a period of over 30 years, 1945 – 1978. Xhafer Deva spoke and wrote seven – eight languages. His correspondence is: Albanian, English, German, Italian, French, Turkish and Serbian. Xhafer Deva’s letters and writings, with the exception of those in Old Turkish and Serbian in Cyrillic, are mostly typewritten, well-kept, and alphabetically arranged, with the persons he dealt with.

That includes his family letters. He carefully kept a copy of every letter he sent and every letter he received. Mrs. Oswalda Deva, daughter Burgl, son-in-law Dennis Logie and Mr. Qefali Hamdia with family, expressed his heartfelt thanks for the trust they gave me. With special gratitude I recall here the help given to me by my brothers – Captain Nue Gjomarkaj and Nikoll Gjomarkaj, in the preparation of one of the most important chapters of this book.

Kapidan Nou, in addition to making available the subject on Xhafer Deva’s relations with the ‘Independent National Bloc’ and sending paratroopers to Albania and Kosovo, reviewed with me each document of that period, and we formulated the text in the form of a conversation; while Nicholas, deciphered the letters, transcribed and translated from Italian, the unpublished materials to date, which were published in this chapter.

Continues from the last number

Xhafer Deva’s life and activity in exile

– Kosovo in the time of ethnic Albania –

Xhafer Deva in the light of his own letters

To write about the knowledge, memories and activity of Xhafer Deva, before and during the Second World War, based on his letters, is not so easy. To say something special about him, in these two periods, one must carefully browse his letters and writings; sentences and paragraphs should be drawn to portray an accurate biography of him. Here are some typical examples.

Xhafer Deva, born and raised in a very rich typical Albanian Muslim family, was a devout Muslim believer. Based on two or three letters, he had during his life made “only one sacrilege” against his faith:

“You know how, after the Qur’an, the good believer does not dare to supplicate to God to bring any harm to the enemy. I brought a big radio from Czechoslovakia, and then there was no television. I kept the radio in the guest room and listened to the news when I had time.

One day I turned on the radio a little louder and listened to the demonstrations in Belgrade with shouts of shouts: “Bolje grob nego rob. Bolje grob nego rob” (better grave than slave, better grave than slave, – I.L.). I got up and prayed to God in a loud voice: – 0 Lord, give me the grave and the slave, let them also see what the grave and the slave is. And God and the Germans gave them (the word is Serbs – I.L.) both “grave” and “slave”.

This description of the Serbian demonstrations in Belgrade before the German occupation of Yugoslavia, Xhafer Deva repeats on two or three different occasions, as in a letter sent to Mr. Gjon Shtufaj and his two other friends. The repeated assertion of such a sacrilege, as the good Muslim believer he was, implies that he had not repented. He was an old, obedient and conspiratorial enemy of Serbian chauvinist policy towards Albanians.

He had followed in detail all the Serbian atrocities against the Albanians. The wrath of retribution had kept him deeply oppressed in his soul, until the right moment, just as his father had advised him: “Be patient, be patient is not ashamed. “When the day comes, it is a shame to be silent.”

In his letters and writings, Xhafer Deva cannot be proven as an extremist against Serbs. His attitude towards Serbs is very clear. From time to time, in various forms, the following expressions of his are noted:

“I wanted to associate with a Serbian intellectual and they respected me. The Serbs settled him in Kosovo for a long time, as we say in our vilayet, the old king, those who speak Albanian like us, should be treated well. The new colonists should to go to their place. “(Letter sent to Dr. Hamdi Oruçi, November 4, 1975).

His knowledge of the political, historical, literary and folkloric developments of central-eastern Europe and the Middle East is inexhaustible. He probably knew the Slavic world better than anyone in his day. He knew the languages of the South Slavs to perfection. In addition to studying historical and literary works in their languages, he had also studied the most popular works in German and Turkish, dealing with Slavs in general and Serbs in particular.

This knowledge is clearly reflected in his letters. He describes the old Serbian history as “delightful Serbian stories and myths and legends created by Serbian monks”, etc. If asked about any issues, he immediately referred by name to the authors and publications, including the libraries where the books were located.

Xhafer Deva was an incomparable reader. He followed everything that had to do with the Albanian issue. During the 1970s, when it seemed that Kosovo was reaching the point of complete secession from Serbia, he regularly read the most popular Yugoslav press, in particular the newspapers: ‘Politika’, ‘Borba’, ‘Nova Makedonia’, ‘Rilindja’ and ‘Flame of Brotherhood’.

Although he received the newspapers late because they came from different channels and personal friends, he saved them all and after reading them, he posted them to me, underlining whole sentences within the lines, and suggested that I read them carefully and t ‘I returned with my opinion about the underlined items. In particular he read ‘Renaissance’.

On the roof of his house, he kept in a cardboard box the collection of some 15 years of this newspaper. Although he was optimistic about the developments of those years in Kosovo, many letters show skepticism about the concrete possibility of secession:

“Serbs are cooking something for us in their kitchen, God willing, we are helping!” (Sentence from a letter dated April 4, 1975).

In the letters sent to Deva, it is noted that many friends asked him to write his memoirs. He responds to one of them: “Talk about my memoirs. I had my adventures told. Rexhepi and Idrizi (Krasniqi and Lamaj) also often told me to write them. The truth is that I have not been involved in politics until 1941, but I followed the events in Royal Yugoslavia.

On March 5, 1938, my father died at the age of 78. Just like his father. He fell into bed and immediately called his mother. Nana got there and he died. No one knows for sure that the father made his will. Of the seven brothers, I have the fifth. He appointed me as the executor of the will. It was there that I saw for the first time how much he trusted me and how much he loved me. He also has ‘muhajir’, leaves and grows in Nis. There he performed ‘Ryzhdija’, in Nis. He had the respect not only of Muslims, but also of Serbs.

There is a very wise and very prudent man. Twice the mayor and twice he were forced to hand over Mitrovica to the Serbian occupiers. How Bektashi was a good, far-sighted Albanian and gave his sons the best education. They are among the only ones in Kosovo who have had the vision of progress. He has given me a lot of advice. I tried to keep them. In the obituary published in the notebook ‘Politika’ of Belgrade, written by Gligorije Bozovic, the author equated my father with Ford, etc. etc.

Even my lady pushed me to write my biography. However, the biography should include the pros as well as the cons. Biography is like a complete painting and not like a cartoon. I do not know the reasons you mention in your letter, why they did not write their biography. I’m sure age also has to do with this. I’m closing with that. I hope that we will have the opportunity to see each other and spread the word “. (Letter sent to Dr. H. Oruçi, November 4, 1975).

In his letters are found many nostalgic paragraphs of early memories. He often mentions how the gigantic figure of Isa Boletini was ingrained in his eyes and in his mind, which he had seen as a child, when he passed the Mitrovica bazaar. Xhafer Deva claims that his father had a close friendship with the Boletins. He says that Isa Boletini’s mother and his mother exchanged frequent visits after the Boletins settled in Mitrovica. Another friend writes:

“Before the liberation, a Serbian general with the surname Tomic, had given the order to take me hostage and to isolate me in the command of the Gendarmerie, on April 8, 1941, in Mitrovica. I was appointed Mayor. Some 300 Chetniks were in Mitrovica and often killed people, of course Albanians. On April 17, Germany entered with a division. Less than three days passed and I agreed with the German general trip to Kosovo and choose two Albanians (from the parish) to appear on the 23rd in Mitrovica.

This is what happened and in the hotel “Jadran” a meeting was held and liberation was proclaimed. The Albanian administration took over the civilian power. We did not have a single man as prefect. During my trip, I ordered deputy mayors and mayors. The Germans were looking for work, and we did not have anyone capable of managing official affairs, etc. I had to keep some Serbs in office and immediately word came that Deva had sold Kosovo to Serbs. So some thugs had decided to kill me, three people had been appointed to carry out the murder. One day it happened that I found the third one in the café of Shemsi Velis (Gjinaj).

I went straight to their desk and told them that if you decide to kill me, here I am. None of them played the vein, nor did they play the finger. I had to tell this story to let them understand what we are, what dough we are. I am of the opinion that not only in Gurbet, but also in today’s Kosovo, Albanians have not changed. We are in exile and have nothing to share. As I said in my speech before the body of Kalosh Hamdis, in Kenosha, on July 18, 1973, “The Albanian is the greatest enemy of the Albanian.” One builds, 100 destroy. (Letter sent to Mr. Shtufaj 3.9.1975).

Meanwhile, Esat Bilali asks Xhafer Deva about Dostan Rexhepi, a prominent figure of the anti-communist war in Lume. He responds to Mr. Bilal, November 2, 1973:

“Every time I read or hear that one of the immigrants has continued his studies in the USA, I rejoice. I understand that you have the BA of New York University. I wish you to have the MA soon.

“Dostan Rexhepi: If I am not mistaken, they had it at the end of September 1944. Arsllan Zeneli and Miftar Spahia, had come to Prizren to seek the help and support of the Second League of Prizren, to explain that the communists had surrounded Muharrem Bajraktar and in the direction of attacking Kukës. After fulfilling their material and financial needs, together with Tahir Zajmi and a Company of the “Kosova” Regiment we left for Kukës. When I got there, I went to the German commander, responsible for securing the Shkodra-Prizren road.

The German withdrawal had begun, but I wanted to get information from him about the situation. He confirmed that the communists had approached Kukes and an attack was expected. The major was named Frank and wrote a book. Prof. Krasniqi has his book. The Mayor of Kukës was Xhafer Aga. That’s where we started our counterattack preparations. The commander of our company was Shahin Gradica from Podujeva. On this occasion I met Dostan Rexhepi, who became the leader of the operation. We crossed the Trail and the war broke out. The position of the communists was much more favorable to them. Major Frank had given me some Italian tank with two Germans. Dostani approached me and told me why he was not giving the order with the shots.

I have told him for a long time. I told Shahin to improvise a slow retreat, as soon as the communists were given the courage to descend on the Path. I told the Germans to shoot a few times and return to the Trail. Shahin had the order that when it got dark – it was near evening – he would disperse the soldiers and hide in Shtigjen’s houses. Dostan did not part with me and told me; the communists will enter Kukës. In Shtigjen, a man from Gjakova had a smoker whom Dostani had told me was a communist. I told him to go to his dugout. No, he told me. I said, come with me. He received us very well but he was also shocked. I looked at Dostan and said: The communists are gone and now our work is over here.

You made us a coffee and we went to Xhafer Aga’s house. There I told him that the communists would enter the Path and let us see! Towards midnight crisis chaos in Shtigjen. Around morning we went there and found communists killed and wounded. Those who had survived had fled. Xhafer Aga took care of burying the dead. Since then, Dostan has not left me. In the war in Dragash / Dragaash, he was close to me and always protected me by putting stones in front of my head. The communists were above us, but we had to continue the war in very difficult conditions. Our losses were considerable. There we parted from Dostan. At that time, Mr. Krasniqi was the Vice President of the League.

When he saw that I was leaving somewhere, he said to me: – Why are you going? Maybe he was right. Tahir Zajmi was the Secretary of the League and he never left me. After the communists entered Prizren, they went to the building where the League was. They found everything in order, in the account and in the untouched money. We have done our duty with full dedication and our free will. No one has forced us. Some hours, who enjoyed life at the same time and are now in the USA, have branded us as fascists, Nazis and even drachmas, etc. But those who have not left their country appreciate those few of our deeds. “Future generations will have the final judgment.”

After the Madrid Meeting, Deva often wrote to Lec Shllaku, editor of the magazine “Koha Jonë” and Secretary of the Madrid Meeting. The correspondence shows their efforts to realize the union of the diaspora. In a letter sent to Shllaku (8.9.1974) Xhafer Deva writes:

“We have been in exile for 30 years now and we live in advanced countries. It seems we have learned nothing. I speak for those who are educated. When 28 Nandori is celebrated, we try our glasses and say: “N’Mot, in free Albania”, etc., and when it comes to doing something for our country, we fight for nothing. The spirit of Madrid was to unite, to put aside all personal and collective differences. The main purpose was to align our powers, etc. What power? We have neither the weapons nor the planes needed for war. What is left of us is intellectual value and will strong, not ideologies, such as: Monarchy, Republic, etc.

In the end, these ideologies do not belong to us in exile. What the people expect from us is to ensure the freedom of that people. In the first place we must investigate whether those people really and in the majority are against the system of government. A generation separates us, and reality teaches us that our mentality does not agree with the mentality of those who live in Albania. Solzhenitsyn himself, the Nobel Prize winner, a great writer, is not (as the Gulag Archipelago says in his book) satisfied with the system of democratic governance, especially in the USA. Our Act-Agreement uses the words “overthrow the regime” These words show our megalomania, i.e., our mentality, regardless of what tools are at our disposal.

The communist regime in Albania can be overthrown from within and not from without. Those who claim to establish the Monarchy in Albania, without giving freedom to the Albanian people, are not only very wrong, but also ignorant of the facts. What are those who, without thinking, say that I should have so many members in the Steering Committee, etc.? They have not learned anything from the past. I expect others to do the job and they to gain ‘namin’.Memorie.al