Part Two

Memorie.al / Favorable winds were blowing in Czechoslovakia. The weather promised spring. Alexander Dubček, having come to power, was undertaking reforms that promised the democratization of the country. Unfortunately, this period of hope lasted only a few months, from January to August 20, 1968, when the country would be occupied by the Soviet Union and the so-called “Prague Spring” would come to an end. But what was happening in Albania in the meantime? Lawyer Spartak Ngjela describes this period in his book “The Bending and Fall of Albanian Tyranny,” published by “UET Press,” Volume I, Tirana 2011.

Continued from the previous issue

Lenin had undertaken this thing earlier when he broke away from the Second Socialist International and created the Comintern, which was nothing more than a Third International. But Trotsky, after being expelled from Russia, also created his own communist international to oppose the Comintern and Stalin’s party, but I have the impression that Hoxha was completely unaware of this fact.

To all of us, this new work of Hoxha seemed like an Albanian folly, and Enver Hoxha himself resembled a swindler who mocked his victims. In “Broadway,” they openly ridiculed all the news from “Radio Tirana” and the newspaper “Zëri i Popullit” (Voice of the People) when it concerned the creation and activity of the Marxist-Leninist parties in the West.

Suddenly, names such as Jacques Grippa, the chairman of the Marxist-Leninist Party in Belgium, Reg Birch in England, Wilcox in Australia, Frans Strobl in Austria, Fosco Dinucci in Italy, and all sorts of other names began to emerge and be propagated as figures; all adventurers who came here to get some dollars, but Hoxha did not care, because he needed them for the purpose we discussed. Above all, Enver Hoxha needed the empire to exercise his propaganda on the populace, especially with the young people he had taken from ordinary work and was promoting into the Party leadership, and who still did not know why they had come, why they had been called, and what they had to do.

Meanwhile, we who lived near Enver Hoxha’s court accurately observed that the entire old guard living around him was not at all enthusiastic about the Marxist-Leninist parties in the West. They were unconvinced, and the opposite had occurred: instead of taking this as a sign of Enver Hoxha’s “greatness” as a doctrinaire, they had taken it as a sign of his weakness for a failed endeavor. I noticed this in my father too. Kiço did not want to talk about them at all, and I understood that he found them ridiculous.

I saw this myself, especially when he did not want to spend any time with the Belgian Jacques Grippa, while he was vacationing with his family, just like us, in Dhërmi of Himara. I saw that he completely disregarded him and avoided meeting him. “What is this? What does he represent?” Vera asked Kiço about Jacques Grippa, one night when we were playing cards, but Kiço initially avoided the question, merely shrugging his shoulders. Vera did not stop and then told him: “You have spent time with him often, that’s why I’m asking you.” Kiço then replied with a sigh: “Why do you ask me, Vera, haven’t you seen that he knows nothing, he doesn’t even know how many members his party has.”

That was all; therefore, Kiço’s generation did not accept this initiative of Hoxha at all, but he didn’t mind, because he had created Ramiz Alia’s group and was paying and paying to create a kind of Communist International, but without calling it such. This, then, was his ridiculous empire, but he loved it. Indeed, if it was not a demagogic game and he truly believed it, then his illness was too severe.

I have the impression that he may have eventually convinced himself that he had finally formed his empire, because from the late 1960s until 1976, he behaved in the media like an emperor of the revolution, as a leader of all progressive movements in the world, and as the spiritual guide of about forty Marxist-Leninist parties that he himself funded. Meanwhile, the hordes that emerged from the event of February 6, 1967, screamed and yelled about the successes of the Marxist–Leninist parties and the worldwide domination by Enver Hoxha.

We couldn’t understand whether these people believed what they were saying or not, but even though we laughed heartily at them, we were still upset. We understood then that a day would come when all political, moral, economic, and social life in general would fall into their hands. “Oh God!” an acquaintance of mine would say more and more often during those times. “What have we done to you, that you are torturing us by crushing us with ignorance?!”

II

The propaganda was feverish, but “woe to us where we had to live.” This was the phrase I constantly repeated to myself as I read everything I could get my hands on about dictatorships and totalitarianism, including “Stalin” by Isaac Deutscher, several monographs on the French Revolution, especially those by Edmund Burke and Thomas Carlyle. Carlyle’s work fascinated me, as did the Stalinist system of gaining and maintaining power, according to Isaac Deutscher.

I felt it was exactly the same thing, despite the fact that, after all, I was living at a time after the French Revolution, when everyone thought that revolution was an ongoing process, while normality was reactionary. It was a troubled time when no one could clearly foresee what the future would bring. In fact, half the world lacked statesmen, and therefore it was led and ruled by “revolutionaries.”

Every coup d’état brought a revolution, and every colonel forcibly aspired to power. In Albania, meanwhile, a new, shapeless ideology was suddenly created, made according to the will of one man, who no longer had any responsibility and needed to start a battle to overturn everything.

Hoxha felt that the forces he needed had arrived in China, and he could take everything from them, everything he needed to consolidate his own economic power.

But there was also something else: he did not know what economy was, he did not know what the market and economic efficiency were, he did not know what production was, and therefore he thought that, with a “revolutionary spirit” and autarky, he would be eternalized.

Folly, in fact, is fed and progresses into utopian spaces through the ignorance of things, and this was the nature of the “revolutionary” power that was being structured in Albania. Months passed, and I felt that my confrontation with that state would be inevitable.

I had no other way, because, even though I was only twenty years old, I could not end up among the herds of “Rhinoceroses,” who’s “trotting” I had been hearing for ten months, as they noisily traversed the streets of Tirana and all of Albania.

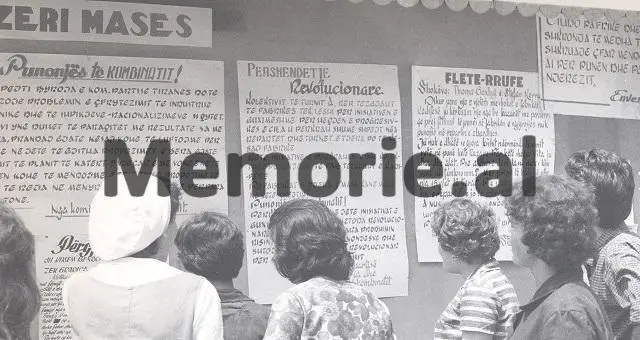

Meanwhile, “Broadway” was buzzing with jokes and humor against Enver Hoxha. But the “Rhinoceroses” had also greatly intensified their fight through leaflets (fletë-rrufeve). You could find them everywhere, in every institution, and especially in the center of Tirana and the main corps of the University of Tirana.

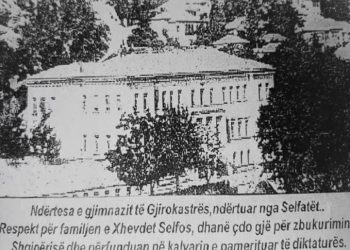

The University of Tirana then had four campuses: one was on the hill, on “Elbasani Street,” and was the Faculty of Geology; below it, on the same street, was the Faculty of History and Philology; near “Mother Teresa Square” were the faculties of Engineering, Economics, and Law; and at the end of the Great Boulevard, near the Train Station, was the Faculty of Natural Sciences; while down by the Civil Hospital was the Faculty of Medicine. All were buzzing with leaflets and fierce agitation against the Tirana student.

They did not leave us in peace for a single moment. Suddenly, they began to attack emancipated and beautiful women, who seemed to be desired targets to release all the unconsumed erotic spite that had accumulated in the “Rhinoceroses” from the life they had led in distant provinces.

The first one they hung the leaflet on was Vera Bekteshi. They spared no insult; they almost called her a loose woman. They attacked her for her clothes and extravagance but said nothing about her intelligence and her level as an excellent student.

And she felt it deeply. She was extremely worried, and, as a close friend of mine, she confided in me with subtle sarcasm: “They are a bunch of ignoramuses,” she told me, “and you do well to mock them all day and call them ‘Rhinoceroses.’ But these women who are trying to get close to the Party committees and whom you know also did this to me; they hate me for my free and complex-free life.”

She mentioned some names, but it does not matter, because everything was actually directed by a hand coming from the State Security (Sigurimi i Shtetit). “Let it go, Vera,” I told her, “this entire movement is not being led by them, but by the State Security.” She paused for a moment and looked me in the eye. I could see that she also suspected it, but I understood that she did not want to believe it, not because she did not know what the State Security was, but she saw it as too serious for her family if the Security had actually attacked her, meaning Enver Hoxha.

She did not want to accept it, but I saw doubt in her eyes. She was too intelligent not to be afraid of the Rhinoceroses; she had accumulated a solid culture and was in her fourth year of Physics. She had esprit, as the French say, but she was destined to fail. The State Security could not accept her, nor could that society which was entirely built against any kind of intellectual elite.

Time showed that it was impossible to do anything with Enver Hoxha, but no one had the strength to change the course of things. And Vera Bekteshi felt and understood this better than I did; she was a woman, moreover a woman with high intelligence and the politics of intrigue in totalitarian courts often have a feminine nature.

Later, ten years later, when I was in Ballsh Prison and the Security itself came and questioned me about Vera Bekteshi and wanted to arrest her for political activity against the regime, this conversation came to mind, and I thought anew that I had been absolutely right even then when I had formed the conviction that the entire “Rhinoceros” movement was directed by the State Security. Memorie.al