Part One

-A year after the establishment of diplomatic relations with Tirana, Bonn sends the first “explorers” to the “land of eagles”! –

Memorie.al / A rare material prompted us to publish almost in its entirety the contents of a reportage published in a special issue of the prestigious German magazine (at the time “West German”) “Stern” in 1987. A group of journalists certainly equipped with photographers, thus become witnesses to an atmosphere as hopeful as it is painful for the Albanian people, in the last years of the existence of monism. Arrived as tourists and carried in “luxurious” buses (for the standards of the Albanians of the time) equipped with air conditioners, they see a bitter reality, although they try to be as objective as possible and reflect what they really saw, also giving us many positive sides of what is now known all over the world as; “Albanian hospitality and generosity”.

Although some description or some paragraph in this article may seem “inaccurate,” in general, most Albanians will find themselves there and remember the time when they lived in a time where queues in stores and pronounced economic shortages had become, let’s say, a “daily refrain,” truly for the already more than tired Albanian socialist society.

While the break-up with the Soviet Union and China had been left behind for a long time, the newly established (though very delayed) diplomatic relations with the Federal Republic of Germany, and perhaps the latest movements of the Alia regime, make the Germans themselves see and evaluate with some optimism and a positive eye even the few “achievements” that could have been realized by the Albanians until then. But, in any case, the reportage in question speaks for itself, which, with very few abbreviations, is brought to the reader in its (translated) form almost in its entirety.

“I bet you’ll have to get a haircut at the border!”

The retired merchant from Göttingen, who is with us and about ten others on the same bus, seems happy. “Gentlemen!!!” he quotes the rules that must be followed during the trip from the manual he holds in his hands, showing me my wallets that have almost taken on a wavy shape, “the haircut must allow a clear view of the face without covering the ears.”

Three centimeters are allowed. Whoever breaks the rules gets a haircut from a barber who is paid by the state for this job at the border. And my golf pants will be the first to suffer. With them, I certainly would not be allowed to cross the border, where fashionable clothing must be avoided.

But where exactly is the border? In the 17-kilometer distance from the Yugoslav city of Titograd to the border crossing point, Hani i Hotit, no sign can be seen to indicate this. Belgrade and Tirana do not get along well with each other: Albania has lived for decades with the fear that the big socialist neighbor to the north wants to swallow the small country – with an area the size of Belgium – by force.

And on the other hand, the 23 million Yugoslavs are afraid that the nearly 2 million Albanians in their country – victims of the fragmentation of the Balkans in 1912-13 – dream of nothing but reunification with the about three million other brothers and sisters across the border.

There have been many riots and uprisings by Albanian nationalists in Kosovo, the “home of the poor” in the south of Yugoslavia. So Belgrade is not that interested in building good neighborly relations.

“Albania is equal to prison,” says the border official from the Yugoslav side of the barrier, whom we seem to have disturbed somewhat while he was playing chess with his colleague. “And what do you want there? Holidays? Aha, better in Yugoslavia!” It takes half an hour before we reach the border on foot, with our suitcases in our hands, like refugees who can barely drag them behind them.

Ten minutes we stand in no man’s land. A soldier with an automatic rifle on his shoulder stops us. Then, an official who spoke German welcomes us with kindness. As for my hair and long pants, he doesn’t seem to care much. The merchant from Göttingen looks at me disappointed and somewhat confused. But there was a barber there before?!

With a thin voice, the customs officer asks us: – “Do you have pornographic material or a Bible with you?” Both are equally forbidden.

In Albania, where the dictatorship of the proletariat protects all the interests of the workers (at least that’s what the official version says), God and “Playboy” are of no use. “Degenerate” literature is confiscated (and when you leave the border again, its return to your hand is, however, more than guaranteed).

From the wall of the control office, a slogan greets us with a quote from the party founder Enver Hoxha: “We will even eat grass and not violate our principles.” It seems there is enough bread in the country. Beyond the window of our air-conditioned bus, which the state tourism agency “Albturist” has made available to us for our 14-day trip, we notice a landscape planted with vegetation, with golden wheat and corn, to the left and right.

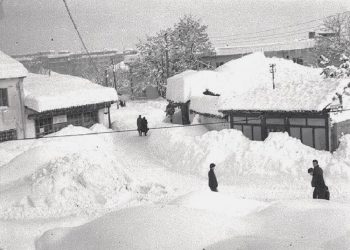

Beyond the cornfields, the sun shines brightly. The brigades of peasants are harvesting the wheat, by hand. Private cars in the People’s Socialist Republic of Albania are an unknown concept. The symbol of freedom of movement is only the bicycle. It costs approximately a monthly salary. A band of pedestrians can be seen walking along the road. The roads are filled with livestock. Only very rarely is the calm of this sight broken by the suffocating noise of the “Diesel” engines of some Soviet or Chinese-made truck.

To the left and right of the road, beyond every intersection and every sign, a dozen bunkers for one or two people stretch out, looking as if they sprouted from the ground. With their empty loopholes and filled with vegetation, they look most like gigantic mushrooms. Under those reinforced concrete constructions, men and women are supposed to defend their homeland “Albania,” the “land of eagles,” from all external enemies. Enver Hoxha, the “father” of the new Albania, has erected them throughout the country’s territory.

If their military value is in doubt, in the psychological aspect they give the Albanians, who have always been trampled by various peoples (such as the Greeks, Romans, Turks, Italians, and Germans), more security. Since Tito in 1946-’47 sought to make Albania his own; the “sons of eagles” have been under constant threat from the outside world. About two hundred Albanians look at us with surprise. Our bus, which stops in front of the “Rozafa” hotel in Shkodër, for them we are like a real circus troupe.

Curious, they look at our shoes, shirts, jackets, cameras, and suitcases, which we carry ourselves to the hotel. Luggage carriers (porters) are not known in Albania. The majority of our groups members, this kind of reception make them feel bad at first. After all, we have come to this country to visit, not the other way around, right?!

The hotel staff starts to move. Toilets for tourists and a special dining room are prepared. A waiter shows me the way I have to go. We will eat in ten minutes. “Mirëdita,” I say in Albanian.

“Guten Tag!”

-“Do you have cold beer? It’s about 30 degrees here.”

The waiter laughs. -“Cold beer?! You speak Albanian? Where are you from? From Germany?”

“Sit down!”

“Now you’ll get the beer. Cold and right away.”

A dozen people surround me, offer me cigarettes, and talk to me. They laugh. One of them puts his arm around my shoulder. -“Where did you learn Albanian, comrade?” – I can only speak a few words in Albanian, words I learned in Kosovo. The Albanians pat me on the shoulders a couple of times. The other members of the group look at me as if they are confused. The same people, who previously seemed impolite, become so friendly so quickly.

My initial vocabulary proves to be a wonderful weapon. Albanians, who gladly rank themselves as descendants of the pre-Christian Illyrians, are fierce nationalists. They greatly honor their language, which over centuries of invasions and despotic regimes has often become the main common cultural and political element of this small and divided “people.”

A foreigner who tries to learn the language gets the greatest respect from them, a respect that is then embodied in excessive generosity and kindness. Honor, personal as well as that of the nation, even to this day for Albanians is above all.

It is not for sale. The waitress at the “Rozafa” hotel demonstratively gives me back the change that I had consciously left for her as a tip. I insist stubbornly. She raises her eyebrows. Respect, comrade.

Gifts make you indebted and one day they must be paid for. Comrade Enver Hoxha experienced this, when the Soviets in 1961 for their many years of aid (200 million dollars) demanded gratitude and from Tirana, they wanted reconciliation with the “eternal enemy” Tito, as well as the establishment of a naval base.

Hoxha, despite his great love for his idol, Stalin, drove the Russian revisionists out of the country. In the current course of reforms in the Soviet Union, the Albanian leadership sees nothing but a form of degenerate capitalism, which has thus betrayed the ideals of October.

After the Russians came the Chinese, who invested with economic aid of 800 million dollars. The pure friendship with the friend about 10,000 kilometers away was broken in 1978, when even Mao’s successors embraced the revisionist course.

They established relations with the hated enemies, the USA, and opened the doors to the Empire of the Third World, Western capitalism. Since then, the People’s Socialist Republic “which relies entirely on its own forces,” has been living immersed in the isolation chosen by itself.

It is the only country on our globe that does not yet know Coca-Cola. Autarky, independence achieved through its own forces, is also the greatest goal. A subsoil rich in oil, iron, chromium, bitumen, as well as a flourishing collectivized agriculture, are what keep this independence alive, “which has created ‘prosperity’ for the comrades.”

“No export, no import,” warn the signs and slogans everywhere. And this also applies to the government. The acceptance of foreign loans is forbidden by law. If verified, it is punishable by death. “Oua”!!!, are heard as the adults curse and wave to the children to leave as soon as possible, who have meanwhile gathered around the buses for minutes to get some gum or some cigarette from us.

The about 500 tourists, who every year flood Albanian cities in collectives and groups with buses – as solo trips are not allowed – have left their traces, despite efforts to stay away from ordinary people.

“Please, do not distribute gifts. Stay in groups. Do not take photos of bunkers or soldiers.” Even photos with views of the facades of uncleaned state houses and people standing in queues in front of shops are against our regulations. / Memorie.al