By Klejd Kelliçi

Memorie.al / At the end of the 40s of the last century and beyond, and as a way to recover legitimacy in their peoples, countries like Germany or Italy began to be interested in recovering the remains of those killed in the world conflict and which were already scattered from Russia, in Africa and the Balkans, so also in Albania. In 1947, the Albanian government recorded all the burial places of foreign soldiers who fell in Albania and their sending to their countries of origin. This was a unilateral act, which did not take into account any specific will expressed by the countries of origin, and especially a country like Germany, which did not enjoy territorial sovereignty.

The orientation also reflected the dynamics of the Cold War, with the material evidence of the Albanian contribution to it, precisely the remains of foreign soldiers, who would have to return to their country of origin. This process was interrupted in the absence of interest from the respective countries and resumed again in 1950, this time not in the form of purification, but rather of confirmation of an ideologically determined position. The consequences of the Tito-Stalin clash and the isolation of Yugoslavia from the Communist Bloc in 1948 had effects not only in the East but also in the West. The Italian Communist Party aligned itself with Moscow, although a small part of the Italian Communists maintained ties with Yugoslavia.

This clash was also accompanied by a competition for the search and repatriation of the remains, in which Yugoslavia, Albania and the organizations of the Italian anti-fascist partisans are included. The association of Italian partisans ANPI, (Associazione Nazionale Partiziani Italiani), dominated by the local Communist Party), asks the Albanian state to act quickly in the repatriation of the remains of Italian partisans, fallen in Albania during the War. Their designation as partisans excludes the vast majority of the remains of fallen Italians, as it deals only with those who had joined the ‘Antonio Gramshi’ Battalion, where after 1943; all those Italians who joined the Army were grouped National liberation.

The no longer diplomatic, but political exchanges between the representatives of the organization and the Albanian state make us aware of the urgent need to transfer the remains to compensate for the similar Yugoslav decision. In the political-ideological competition between the former Italian communist partisans, divided into pro and anti-Titis positions, Tirana also enters, which accepts the ANPI’s request to find and return to their homeland those who had already received the status of heroes, the Italian partisans of the ‘Gramshi’ battalion.

In 1957, the signing of the Peace Treaty between Albania and Italy, foresees the repatriation of soldiers’ bodies. A process that carries, a political ambiguity, since on the one hand it serves the Italian community, to connect spiritually and materially with the fallen, producing a process of collective catharsis on the memory of the war, and at the same time legitimizing a new Italy, truly separated from the fascist past.

For Albania, it is a process of cleansing and almost ‘disinfection’ from a pathology that appeared from a new beginning, which most likely excludes the cyclical repetition of the invasions of Albania in history. The repatriation of the bones, apart from being a political act, would also be considered a humanitarian act, but of a humanity that recognizes as such, only the similar, that is, the Italian partisans, it also humanizes it in the form of recognition the Tirana regime itself. In exchange, this act offers the Albanian party the opportunity to request the termination of the cooperation of the Italian state with the Albanian political diaspora, considered as a foreign part of the post-war reconfigured Albanian body.

The remains of the soldiers, converted into partisans, thus take on the value of the hero, although the Albanian authorities find it difficult to identify the so-called martyrs. This is because many Italians joined the “Antonio Gramshi” Battalion not simply because of their political will, but because of the need to escape the punishment that came with non-acceptance. Carelessness, not knowing the body and the identity of the martyr, leads to the dilemma with which the Albanian authorities are faced with the remains of the murdered…! The senator of the Italian Communist Party, Umberto Terracini, describes the arrival of the remains of the Italian partisans of the “Gramshi” Battalion in Bari.

This act was seen as the good will of the Albanian government, to preserve the memory of the partisans killed in the fight against anti-fascism. ANPI representatives themselves insist on the need to have clear identities of the remains of the Italian partisans, as only in this way can the desired political goal be produced. The identity of the bones will be determined; otherwise the political effect they produce may be grotesque.

However, the process continues and reaches its two-way political finality, that of ANPI that recovers the remains, trying to tell a double story, that of resistance to fascism and political affiliation with the cause of communist countries, moral and material winners of war, despite the political history of Italy, as a losing state. The parenthesis of the repatriation of the bones, of those who already enter the pantheon of the remembered, also opens paths for the forgotten. The process of transferring and exhuming the bones takes place, Italian partisans, which carry a number of risks, such as infection by the bacilli they carry.

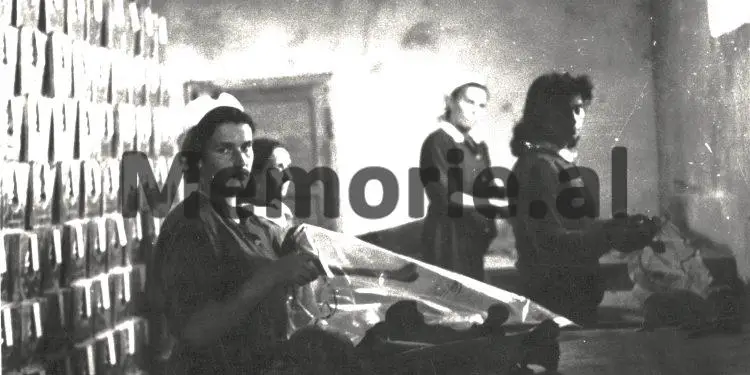

On the Italian side, a group led by General Bandini, a low-ranking soldier and a priest, is created for this purpose. (As is known, all the operations of finding, exhuming, cleaning and transporting the remains of Italian soldiers constitute the bed of the world-famous novel ‘The General of the Dead Army’, by our great writer, Isamil Kadare. Albanian workers seek to carry out this process rapidly, both for reasons of contagion and for reasons of the memories they evoke.

The haste to disinfect the bones, sealed in bags, simultaneously shows the strength that the dead body regains, in the production of tension, the recollection of the war, the events related to it, but also its neutralization from the place in which they will be laid to rest.

When these bodies are taken out, they have the opportunity to infect living Albanians, but also to carry with them the infection bacillus of the foreign body. This is clearly seen in the detail of the illness of the worker who opens the graves and touches the soldiers’ bones without disinfecting them.

The remains of soldiers retain their destructive potential, which comes not only in the living, through the weapons, but also through the bacilli they carry. With the departure of General Bandini’s mission, the High State Control Commission exercises a routine control for the work of the Bones Sector. The official report reveals that during the work activity, the employees and mainly its leaders, had acted outside the objective of the work and instead had harmed the state and violated the trust of the party.

The bones sector was headed by an official, who was appointed directly by the Central Committee; the deputy director was a State Security official. Sworn communists, trusted people, who had fallen prey, according to the report, of the harmful influence that the Italian general had exercised over the Albanians. The official report reveals that during the work activity, the employees and mainly its leaders had acted outside the objective of the work and instead had harmed the state and violated the trust of the party. The bones sector was headed by an official who was directly appointed by the Central Committee; the deputy director was a State Security official.

Sworn communists, trusted people, who had fallen prey, according to the report, of the harmful influence that the Italian general had exercised over the Albanians. The State High Control Commission exercises a routine control over the work of the Bones Sector. The official report reveals that during the work activity, the employees of the leaders and their leaders had acted outside the objective of the work and instead had harmed the state and violated the trust of the party.

Unable to carry out the exhumation activity normally, the Italian general had paid bribes to the Albanians, not so much to enable the exhumations as to compile all the necessary, individual documentation for each soldier found. The State Security employee had taken money and clothes to facilitate the process and had mobilized all the employees in the service of the Italian general.

Put before the responsibility, the security employee is sentenced to prison, while the responsible K.P., is dismissed from office by the Political Bureau, for abuses and anti-socialist activities. P.Ç., is stripped of his rank and punished, not without making a ‘mea culpa’ for the serious mistake. And this is exactly where the essence of the enemy appears, the possibility of the corruption of the young socialist man, weak in the face of temptation, but capable of producing the language of the system in the form of admitting guilt and redeeming it. “Italy was a regular cadre of fascism and we faced a foreign fascist state”, says P.Ç. in front of the facts.

And if in Kadare’s well-known novel, ‘The General of the Dead Army’, which includes the above events, the infection and danger of the dead soldier, comes in the form of the bacillus, which kills one of the gravedigger workers, in reality, the lamentation and the infection comes in the form of corruption, the capacity and ability of the enemy to corrupt Albanians. The association of Italian partisans, ANPI (Associazione Nazionale Partigiani Italiani), dominated by the local Communist Party, asks the Albanian state to act quickly in the repatriation of the remains of Italian partisans who fell in Albania during the War.

Their designation as partisans excludes the vast majority of the remains of fallen Italians, as it deals only with those who had joined the ‘Antonio Gramshi’ Battalion, where after 1943; all those Italians who joined the National Liberation Army were grouped. The no longer diplomatic but political exchanges between the representatives of the organization and the Albanian state make us aware of the urgent need to transfer the remains, to compensate for the similar Yugoslav decision.

In the political-ideological competition between the former Italian communist partisans, divided into pro and anti-Titis positions, Tirana also enters, which accepts the ANPI’s request to find and return to their homeland those who had already received the status of heroes, partisans Italians of the ‘Gramshi’ battalion. The repatriation of the bones, apart from being a political act, would also be considered a humanitarian act, but of a humanity that recognizes as such only the similar, that is, the Italian partisans, it also humanizes the Tirana regime itself in the form of recognition.

In exchange, this act offers the opportunity to the Albanian side to request the termination of cooperation with the Italian state, with the Albanian political diaspora, considered as a foreign part of the Albanian body, reconfigured after the war. The bones of the soldiers, converted into partisans, thus receive the value of the hero, although the Albanian authorities find it difficult to identify the so-called martyrs. This and for the reason that many Italians were engaged in the ‘Gramshi’ Battalion not simply because of their political will, but because of the need to escape the punishment that came with non-acceptance.

Carelessness, not knowing the body and the identity of the martyr, leads to the dilemma with which the Albanian authorities are faced with the remains. The senator of the Italian Communist Party, Umberto Terracini, describes the arrival of the remains of the Italian partisans of the “Gramshi” Battalion in Bari. This act was seen as the good will of the Albanian government, to preserve the memory of the partisans killed in the fight against anti-fascism. Senator Terracini asks the Italian government not to support the Albanian anti-communist exile. The political identities of the remains are unclear, and often the reasons for death as a hero, or as a surrendered Italian soldier, are not clearly distinguished.

ANPI representatives themselves insist on the need to have clear identities of the remains of the Italian partisans, as only in this way, the desired political goal can be produced. The identity of the bones will be determined; otherwise the political effect they produce can be not only opposite, but also grotesque. However, the process continues and reaches its two-way political finality, which recovers the remains, trying to tell a double story, that of resistance to fascism and political affiliation, with the cause of communist countries, moral and material winners of the war, despite the political history of Italy, as a losing state. Memorie.al