From Njazi Xh. Nelaj

Part Eight

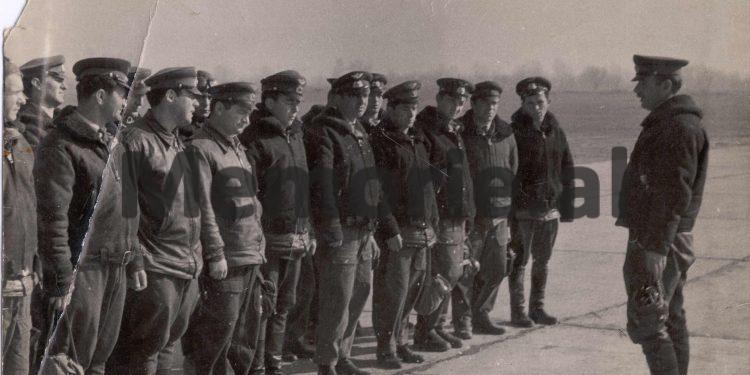

Memorie.al / Impressions and memories from the life of the talented pilot from Tragjas, aviation colonel Niko Selman Hoxha, who fell in the line of duty on November 20, 1965, at the military airport in Rinas, during a combat exercise with a ‘MIG’-17 F jet, in front of the regiment’s personnel and several military academic cadres. The impressions and memories were collected by Niazi Xhevit Nelaj in June – July 2012, in Vlorë, Tirana, Voskopojë, etc., during meetings with people and through telephone conversations, even up to distant Boston. Every meeting and conversation with contemporaries of Niko Hoxha and his relatives has found reflection in this material, with fidelity and authenticity. The monograph reflects only a part of the life of the hero, that part which is related to aviation and flying, and does not extend to other spheres of the multifaceted life of the man who propelled military and aerial discipline and training. Niko Selman Hoxha, as he was orderly, disciplined, and extremely correct, was distinguished in the unit for having an exemplary regimen in life. He did not reside in the unit and did not eat in the pilots’ quality mess, but at home; thanks to the dedication and good management of the situation by his wife, Jolanda, nothing was lacking in his regimen. This writing does not cover Niko’s family life, nor does it touch on his care for his sons, Valer and Sasha, whom he left still young but surrounded with much parental care and love while he was alive. Other writings to follow will surely shed light on those aspects of Niko Hoxha’s life that have remained somewhat in the shadows in this monograph.

The Author

Continuation from the previous issue

Who was Niko Selman Hoxha?

The colonel was accompanied by the young pilot from Sasajt of Saranda, Zija Shyqo Memi. The second pair was led by the first-class pilot Kosta Neço Dede, and, at the end of the formation, there was the brave Tiranas Bilal Murat Josja, one of the most effective pilots of the regiment for ground target shooting.

The four aircraft took off over the airport at a height permitted by the lower layer of clouds and performed a low-altitude demonstration pass over the target. At the right moment, on the command of the formation leader, all four pilots released the onboard signaling rockets as a sign simulating the bombing release, and ascended one by one, turning left, over the villages of Valias and Qerekë to set up the attack maneuver against the target on the ground.

The aircraft piloted by Niko Hoxha, the first in formation, after executing a “deep” maneuver, reached the fourth turn, where the attack began, closer to the target he intended to hit, and entered a dive at a steeper angle than that recommended in the relevant aviation literature. The colonel conducted the attack with live ammunition and began to “pull” the aircraft out of the dive at a slower pace than what was required in this case. When his aircraft was flying level with the ground, directly above the heads of those observing the flight, the colonel had given the aircraft the position needed to touch down, but in this instance, its progressive speed was approximately 700 km/h.

With this speed, the airplane touched down with the bobbin (a duralumin knife placed at the rear end of the fuselage, meant to prevent damage to the aircraft during hard landings). The contact of the plane with the ground caused the opposite action. We saw the aircraft leap back into the air, pass over the canal, and then burst into flames as it skidded into the harvested cornfield. The pieces of the burning aircraft, divided into three parts, were found in the middle of the plot. The aircraft’s ejection seat had exploded, throwing the colonel out of the plane and to the right. We ran towards the burning plane, hoping that perhaps we would find him alive. We could not believe our eyes, even though the incident happened right before us.

Seated in a MIG-17 F, I was in Zone 1, ready to start the engine and take off into the air to conduct the shooting exercise that remained from the annual flight plan. The engine start lever was located just after the point where the machine’s electric cables (APA) connect with the aircraft’s electrical node. I had my helmet on and the radio in normal working condition. Through the radio and with my eyes, I observed and listened to what was happening around me, as every pilot does in such moments while waiting for their turn to take off.

I followed the maneuver of the pilots and saw from the cockpit of the plane where I was seated what happened to the colonel. I saw him and was horrified. I couldn’t give it any other name than what my eyes perceived. In an instant, I released myself from the straps that secured me to the aircraft’s cockpit, jumped down from the plane, climbed into the launch vehicle, and took off at the speed that the special vehicle generates towards the burning aircraft. Like me, others did the same, as those who were in Zone 1 and throughout the airport. A crowd of people rushed from Valiasi, where the families of the regiment’s officers and random workers from the farms and agricultural cooperatives around lived, to reach the scene of the event. I might have been among the first to cross the wide canal at the end of the airport and jumped into the field beyond.

Pilot Bashkim Agolli, a small-statured individual, remained in the canal and was drowning; his friend, a pilot from Kllojka in Tirana, Adem Ceça, a giant of a man, grabbed him by the collar (this is how we jokingly referred to Bashkim Agolli) and pulled him out. Everyone was rushing as fast as they could to see up close what was burning and what remained of it. After the explosion, Niko’s plane broke into three parts, and each piece skidded into the field, leaving behind a trace of flames and smoke together. I might have been among the first to reach the body of the pilot that was burning.

Perhaps this was not the natural way of speaking, but it manifested itself when he began practicing the profession of a prosecutor, and day by day this habit thickened, taking on the proportions of a vice, ultimately displacing his personal nature. Just where the park space begins before the state buildings on the first floor, and on the right side, the gravel road branches off to go to the bakeries, I almost collided with Prosecutor Bardhi because, at that moment, I was looking down, captivated by the “small” connecting bridge between the park’s curb and the street, separated by a narrow canal, and did not notice.

– “Where are you rushing off to?” I asked him, forgetting that this was his usual pace.

– “How nice to see you!…,” he said. “Do you have some free time, and would you like to take a walk together? Or has your mother-in-law tasked you with something?” he added with a smile.

– “With great pleasure! But with one condition: reduce your walking pace by three times,” I replied.

– “Though a tough condition for me, I promise to fulfill it,” he said, linking his arm with mine.

– “Are you coming straight from work? Surely the overload forced you to disconnect from the files…?!”

– “We have quite a tiring and stressful workload!” said Prosecutor Bardhi. “The nature of this job deprives us of many rights. First of all, the duty of the prosecution limits our social life: I cannot talk in a public setting, and I cannot have coffee with someone I like. Because the harsh shadow of the duty always intrudes. Here we have a concrete example: anyone who sees us walking together, arm in arm, will think I am committing the greatest sin since the cynics view the class struggle of the Proletariat’s Dictatorship only through dark lenses.

According to them, we belong to two opposing camps, and we should be positioned in different trenches; thus, social and friendly ties between us cannot exist! Even though this mentality and such distorted relations cannot be described otherwise than as terrible paradoxes, they often occur in our daily lives! These corrosive phenomena hinder the progress of society. But more than anyone else, the consequences of class divides are felt by the guilty without guilt!

Writers, as the most sensitive part of society, find themselves facing a duality of reality through the method of writing, which causes confusion with contradictions. It is precisely here that the harsh class struggle of socialist realism begins; the separation of the two groupings targets the talented from the elite, determining the conditions for who will be kept in the Writers’ Union, who will be discarded, and who will be deported or imprisoned! Certainly, I tell these thoughts to myself, to no one else. You are the first to hear them from my mouth. As a lover of literature, I dedicate my free time to artistic reading, and now I feel pleasure in discussing and exchanging thoughts with a writer.

The colonel was honored and accompanied, as he deserved, to his final resting place. He was buried with a funeral ceremony, complete with flowers and passionate speeches, at the Sharrë cemetery, in the first plot, against the enclosing wall, near his comrade and deceased colleague, Lieutenant Colonel Peço Polena. During those days, pilot Çobo Ibro Skënderi, who loved and respected Niko Hoxha greatly, wrote the following verses:

“Here rests a soldier,

The simplest among the simple,

A very brave pilot,

A commander, among the most modest.”

These found verses, dedicated to the figure of that hero, were engraved on the headstone of his grave, and the place where the colonel rested for a long time became a “shrine” and a pilgrimage site for those who loved him and cherished our aviation. Years later, Niko Hoxha’s grave was transferred to the Martyrs’ Cemetery of the Fatherland, along with his comrades and subordinates, who met the same fate. We saw Niko with our own eyes as he fell and as it happened, but many others who fell were not seen. Each of those who fell in aviation gave their lives, the most precious thing a person has, in service of elevating the force.

The tragic event where one of the pioneers of aviation, the brave Niko Selman Hoxha, lost his life caused a great stir and much sorrow and sadness. But there were also positive reflections. The pilots overcame their grief with the courage and bravery that Niko himself had instilled in them. Analyses were conducted, and theoretical and practical examinations were held, and life flowed as it knows how to flow. The people’s sorrow was expressed in various forms, and their sentimentality showed through. The great Albanian writer, Ismail Kadare, when he received news of the heroic death of pilot Niko Hoxha, wrote:

“You loved this land so much.

You often approached it with terrifying speed,

One day, you approached so much,

That it reached out its hand and took you in its embrace.”

With these verses, the great writer seemed to have stamped the opinion of the time regarding Niko Hoxha. Our people have honor for the brave in their genes. The people of Tepelena, continuing the tradition, expressed their respect and sorrow through song. One thing is clear: if you find a place in the people’s songs, you are surely someone significant. The elegiac song of the Tepelenas resounded powerfully in those days:

“Albania fell into mourning,

Radio-Tirana announces:

A tragedy has occurred,

The commander of aviation,

Known for his bravery,

Has flown high, into the sky,

No longer returning alive,

You did not release the aircraft,

But died along with it.”

The verses and sayings connected to the heroism of Niko Hoxha echo his heroic act and serve to immortalize him. Things flowed in their course, and life continued as before. People emerged from the shadows and returned to their work, many of the Colonel’s students grew up, both in age and in profession; some became leaders and experienced personnel. It is the honor of each one to look back and read without emotion the entire work of our tribune, Niko Selman Hoxha. The foundations laid by the colonel 50 years ago, related to the training of pilots and aircraft for flight, and the levels he set, which were surpassed by his students, regardless of the changes that have occurred in technique and technology, remain reference points for today and the future.

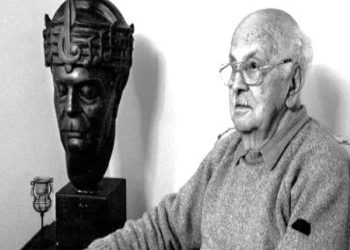

Time took its course, and the tribune remained there, in that harvested cornfield, beyond the runway of Rinas; some of his contemporaries and those taught by the colonel are now aged, to the point where they must think hard for a while to say something accurate about the hero, but the echo of his deeds comes to us fresh, like a breeze that caresses us and reminds us, even though the time that has passed is long. After the incident, conclusions were drawn and tasks were set to improve the situation, newspapers of the time were written, reports were adapted, a bust of the colonel was placed at the center of the unit, and the Rinas regiment was named “Niko Hoxha,” a name that was once removed and then given back, reflecting people’s sentiments according to political circumstances.

I do not have the ability to judge what has already been judged once, let alone to remove the scab from a wound that has hardened, but I do have some reservations, and I do not keep them to myself. In aviation, serious incidents have occurred, which in some cases have ended in catastrophe. Such is the nature of the work; such is the unique profession of a pilot. Therefore, when an airplane passes overhead, people instinctively raise their heads and want to observe it. This phenomenon transcends the nostalgia that people have for the air and the airplane, but it also serves as homage to those who break through the skies, risking their lives.

If you read the conclusions of aviation incidents without looking at the name of the unfortunate pilot, the conclusion becomes repugnant; pardon my vulgar expression: “the causes are human.” Thus, the incident is covered up, following the old slogan: “the living among the living, the dead among the dead.” At a cursory glance, the conclusion about human causes may be correct, but it seems to me that it does not apply to all cases. It is the incompetence of people who do not delve into the depths of phenomena to reach the truth.

Without taking a moralist stance and without placing myself among those sentimentalists who put passion before logic, I say with conviction that the above slogan does not apply to Niko Hoxha. Colonel Niko Selman Hoxha was and remains a hero, with a capital H. His work speaks for itself. Its echo, as it has come to us to this day, will surely be conveyed to future generations; the honor for that man cannot be extinguished. Time passes; some are left in the shadows or forgotten, but the legacy of Niko Hoxha will rise higher and higher, as happens with true tribunes./Memorie.al