Memorie.al / In the city of Korça you find characters who recount their lives. They don’t stop talking, but when you ask them to write, they hesitate a little, then give you the right to write. The guarantee is given when they hand you the photos. Just don’t burden the writing with other stones; besides these that we give you, they also give you this advice. In people who have suffered, you always find their fountain. You find their winter. You find their piece of autumn. To ensure that what they have expressed to you says that so-and-so knows it too because we were there together…!

Waiting?!

While waiting to receive compensation for his years in prison as a political convict, Namik Spahiu passed away a short time ago. With a rare sense of humor, he would talk about his conviction and his years in prison. “In prison, some of our friends would put on variety shows, where they cursed capitalism and revisionism. Meanwhile, the painters wrote slogans: ‘We dance in the mouth of the wolf’, ‘Albania a granite rock’.

It fell to me to hold the cans of paint while the painter Maks Velo wrote the slogans. He tried to overcome that injustice which he called the sentence, where from a staunch communist, he ended up in Spaç. ‘You finish your plate of rice, you bums, but why don’t you finish the quota,’ the commander of the prison in Spaç would tell us?!”

The Prison Money

For the people of Korça, Namik Spahiu will be remembered as a laughing old man who, in two words he spoke, would unravel a large ball of yarn behind him. Like many political prisoners, he was waiting to get the compensation he was due. “The governments drag their feet on us,” he used to tell me. Our accounts, like those of properties, were closed until 1996. But our rights are not taken with glasses [of drink]”.

With a cane in his hand, he would often go out to the Municipality bar and spend hours there, amidst humor and a drink. “We are of the society from vodka downwards. Keep drinking, because tomorrow we get our pension,” he would say with humor. He had just started preparing the documents, without submitting them, when Namik Spahiu passed away. He often joked, telling us that; “they will bring us flowers there in Shëntriadhë, at the city cemetery”.

At the Interrogator’s Office

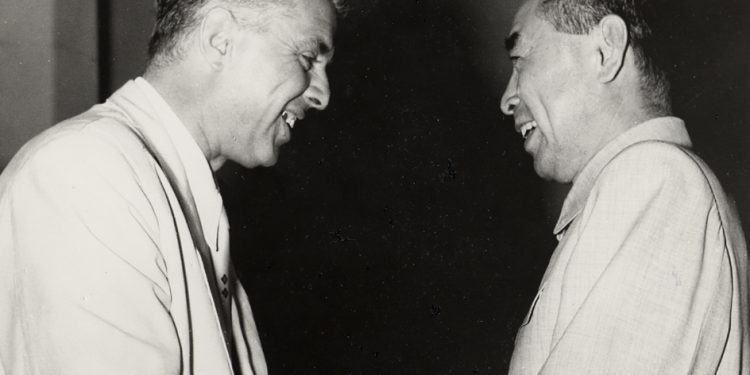

Yes, besides the tortures to make him accept the accusation, Namik Spahiu also had to cry for a leader of China, after the blows the interrogator had given him. He recounted this fact with a lot of humor.

“He knows me. As much as I cried for China’s Zhou Enlai, even the Chinese themselves didn’t cry that much”!

“How, were you in China when he was buried?”

“Not there, but in our cells I cried for him.”

“How did you find out?”

“The investigator told me, from him I learned that the Chinese man had died.”

“But how did you cry?”

“‘Do you know what day it is today?’ the investigator told me.”

“‘Thursday,’ I tell him.”

“‘Thursday, huh, don’t you know that today Zhou Enlai died’!”

“‘How should I know’?”

“Then the investigator kicked me in the kneecap, and with another blow that caught my arm and slid, stopping over my heart. I fainted, and for a week I cried, from the wound I received. That’s how I cried for the Chinese, our former friend.”

Namik Spahiu happened to have this dialogue several times a day. And then he would start recounting how it had happened that he had shed tears for the death of a Chinese leader.

Namik Spahiu, from a communist, an enemy of communism!

Namik Spahiu was born on September 16, 1933, into an old Korça family. He spent his youth in the city of Korça, taking on any kind of work. His dream was to study at a school where he could gain culture and knowledge. He came from a middle-class family, and some members of his family fought with weapons in hand against the foreign occupiers. After the country’s liberation, his mother and father did their best so that Namik, as the youngest of the children, could be educated somewhere abroad, but this dream of theirs was never realized.

However, after finishing the 7-year school with excellent grades, Namik studied at the Economic high school in the city of Korça, with satisfactory results. After several years, he also joined the ranks of the AWP (Albanian Workers’ Party) as a simple member for 17 years in a row, until November 15, 1975, when he was arrested by the State Security forces on the charge of “Political Agitation and Propaganda”.

Namik: “How I washed the cell with tears, for the death of Zhou Enlai”!”

“I had spread the word of the Party,” Namik would begin to recount, “in fact, I was a fervent communist. I tried to work and live by the sweat of my brow. I had honesty and love for my family, friends, and acquaintances as an obligation in life. I never thought,” Namik continued, “that I would be a victim in the heat of the class struggle, as I was truly imbued with progressive ideas and had aimed for solidarity towards people.”

Regarding his arrest, Namik did not hide the annoyance caused by the surprise and the lack of clarification, even to himself, about the injustice done to him, as it had never crossed his mind that he would end up, due to uninformed and inaccurate spies as he says, in one of the most infamous prisons in Albania, that of Spaç. He would describe the day of his arrest as follows:

The Arrest

“I worked as a warehouseman in a sausage factory. When I was returning from work, I was in a good mood on the way, because in a few days I would celebrate my 43rd birthday. My wife and children always waited for me at the outer door and when I turned the last corner of the alley that would lead me home, I quickened my step and the children immediately jumped into my strong arms. After we had dinner and were preparing to sleep, I heard some loud knocks that became more frequent.

I remembered the Germans who, during the War, broke down the doors of houses to annihilate communists or their family members. My wife and children were scared, but I got up immediately and ran to open the door, what do I see? In front of me was the head of crime eradication, Reshat Leskaj, together with some policemen and prosecutors. After looking at me for a few seconds from my feet up to my face, he asked me: ‘Are you Namik Spahiu?’ ‘Yes,’ I answered him. ‘In the name of the people,’ he tells me, ‘you are arrested,’ and another policeman grabbed my arm and put me in a ‘GAZ-69’ [vehicle].

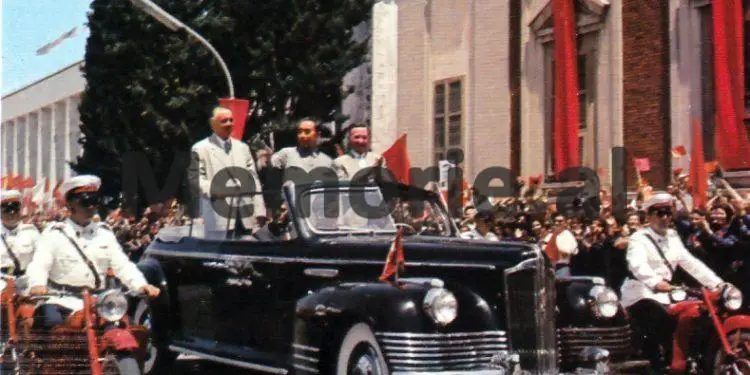

“‘What have I done?’ I said to him, as we took the road towards the investigative office, where it still is today. ‘Shut your mouth, enemy!’, the head of crimes told me, ‘you have cursed our power as much as you could.’ ‘It’s not true,’ I stammered, but as soon as we arrived at the investigative office, they put me in an underground cell, where I did not see the light of day for 7 months in a row. I even remember one day it was Friday, March 15, 1976. The investigator Xhevahir Lika called me and, scrutinizing me deeply, told me: ‘Zhou Enlai has died,’ then Prime Minister of China!

“‘But what do I have to do with his death, or should I answer for this too?’ But he didn’t wait any longer and gave me a strong blow with the tip of his shoe on the kneecap and another blow with his fist that slid down my arm and ended up on the side of my heart. At first I didn’t feel pain, but later only God knows. Those blows made me burst into two sets of tears when they returned me to the cell, and with pain I say that all of China would not have shed so many tears for him.

Then every day the same old story. Threats, blackmail, insults, and pressure – these are all my ears heard. Then the tortures began, by policemen with whips and sleeves rolled up to their elbows. They pressured me to declare myself an agent of foreign services or to admit that I had cursed the members of the Politburo and Enver Hoxha himself for a long time. After seven months, I went to trial with witnesses I didn’t know and where the charge of agitation and propaganda weighed heavily on me.

I did not accept any of the charges raised; it even seemed absurd to me that I, a communist with valuable ideals, should prepare to suffer an undeserved sentence. However, the statements of the false witnesses proved that I was destined to be convicted. And so it was. The prosecutor at the time, Llambi Gegeni, asked for 16 years of deprivation of liberty for me, but the judge decided on 9 years and three months. I was transferred directly to Spaç, to this infamous prison that resembled a real Holocaust. I cannot find words to describe that misery, that hell, as if we were the servants of the devil.

Bad food, filthy and torn clothing, a total isolation. When I was alone I thought a lot about my wife and children. I cried secretly looking through the bars of the cell window at only a patch of sky and life saddened me. Grueling and heavy work that had to be endured with a negligible bread ration. Nevertheless, I thought that I would chew through these years of deprivation of liberty with my teeth, just so that my family would be okay. But it wasn’t long before the second misfortune came. In a letter my wife sent me, she explained that she had divorced me (made hasha) and that from now on she would mind her own business.

I couldn’t believe the letter, even though I was sure the handwriting was hers. She explained to me in the letter, among other things, that she was convinced that I had cursed the Politburo and Enver Hoxha. I was convinced that someone had influenced my wife, perhaps her brothers, or the 1200 spies, who were numerous at that time. She was more communist than the first communists themselves. There was nothing I could do, I saw what I saw, I put a stone of oblivion on my heart for everything, I reset my brain to zero and only imagined the long-awaited day of liberation, which seemed centuries away.

But after all those years I did not forget either my family or my party; in fact, together with a friend, inside the surrounding walls of the prison, at midnight we wrote slogans in ink favoring Enver Hoxha and Marxism-Leninism. Whereas during the day, the prison staff knew us, according to the incoming reports, as the most rabid anti-communists. From the prison cell I also took with me the heart disease, which now caused me even more problems. I served every single day of the sentence the court gave me. When I arrived in Korça, I immediately left for home.

My boys, now even older, came out to meet me and hugged me, looking at me with a kind of surprise, as if I were not their father. It was an indescribable scene, which nevertheless passed. My wife had separated; she had taken the room on the second floor, while she had prepared the room downstairs for me. To this day we do not speak, even though we live under one roof. For her, I remain an enemy of the class struggle, while for me, she remained a communist without tact,” concluded the painful history, which I had heard often, but never tired of. Before reaching the age of 75, he passed away. He passed away without getting his due, the debt owed to be settled by the state./ Memorie.al

![“They have given her [the permission], but if possible, they should revoke it, as I believe it shouldn’t have been granted. I don’t know what she’s up to now…” / Enver Hoxha’s letter uncovered regarding a martyr’s mother seeking to visit Turkey.](https://memorie.al/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/Dok-1-350x250.jpg)