By Andrey Edemskiy

Part Three

Memorie.al / The following material is a paper by Andrey Edemskiy, of the Institute for Slavonic Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences. For the first time, the author presents the previously unpublished archival sources, Funds 2, 3, and 10 of the Russian State Archive for Contemporary History, through which we can see the Soviet perspective on what was happening in relations with Albania in 1960-1961. These sources help to revise several myths in the historiography and the subsequent Albanian collective imagination. The myth of the “battle” at the Vlora base must be viewed beyond the narrow scope of an Albanian victory and demonstration of force, since at least according to the documentation in question; it does not appear that the Soviets ever intended military scenarios in Albania. Nevertheless, the Russian academic concludes the paper by emphasizing the need to compare sources to better understand what happened.

Continued from the previous issue

One thing is clear: regardless of the Soviets’ behaviour or mistakes – which are admitted as such – Enver Hoxha did not leave the split with the Soviets to chance. He had it as a political goal and provoked it to the end, first by collaborating with the Chinese side and second by undermining the climate of cooperation. It remains to be explored what lies behind this policy, but, for example, the author’s interpretation of the meeting in Tirana between him and Andropov and Pospelov suggests that Enver Hoxha felt personally threatened by the Soviets.

And he decided to purge the party of any possible pro-Soviet elements and then, in light of the Soviet-Chinese frictions, to prepare for the escalation of the situation, by publicly standing as a determined communist who had caught the Soviets in an ideological error. It is also poorly clarified, even with these documents, whether Khrushchev’s rapprochement with the Yugoslavs was a reflex of the break with Albania, or whether it was related to a Kremlin policy in the Balkans. The author says that in any case, the rapprochement with Yugoslavia gave Enver Hoxha an alibi, further paving the way for the final split.

The study by Andrey Edemskiy, from the Institute for Slavonic Studies at the Russian Academy of Sciences

Wishing to “make some assessments of the actions of the Albanian comrades, who have recently deviated from the agreed foreign policy of the Socialist Camp countries,” he pointed out several issues. As for the Albanian stance on developments in the Balkans, he was dissatisfied with their refusal to support the “concrete proposals of the socialist countries on the issue of inter-Balkan cooperation, on the creation of nuclear-free zones in the Balkans and the Adriatic,” and even “hindered the implementation of these proposals.” The Soviet leader even made some clarifications regarding the situation at the Vlora Naval Base. He stressed that; “the base is currently practically unable to carry out its duties” and has become a “source of increased friction.”

According to him; “the combat effectiveness of the base is paralyzed” and “under the current conditions, there is no point in maintaining it any longer.” As the sole condition for its preservation and “normalization of the situation,” Khrushchev emphasized the “need” to accept the proposal made in Marshal Grechko’s letter, for “a single command at the military base, so that the entire ship crew can remain Soviet.”

In this case, Khrushchev made it clear that he would not even respond to any speculation against him by the Albanian leaders. There is no doubt that the obligation of the Albanian representatives to consult with Enver Hoxha and their differing political weight, compared to the other representatives at the meeting, did not enable them to respond actively and sharply to the various statements and accusations primarily directed at the highest Albanian leaders.

It is clear that everything that happened at that meeting, including the criticisms of the Bulgarian and Polish leaders, with whom Khrushchev agreed concerning Enver Hoxha’s statements at the last PLA Congress about a plot against Albania by Greece and Yugoslavia, with the participation of the American Sixth Fleet, was transmitted to Tirana word for word. In Khrushchev’s assessments, who suspected that Enver Hoxha had deliberately pumped up a “military hysteria,” he seemed to be defending the Yugoslav leaders in this specific instance.

It is clear that Khrushchev’s comments on March 29, regarding relations with Albania, were related to the further well-thought-out steps of the Soviets in relation to Albania, in both the economic and political spheres. Two days earlier, the Soviet leaders had approved recommendations on economic policy concerning Albania, which were to be implemented by the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the State Committee for Economic Cooperation, and the Ministry of Foreign Trade. The recommendations were drafted in a few weeks, in accordance with the decision of the Presidium of the Central Committee of the CPSU, taken at the end of February.

These “proposals” constituted a foundational memorandum, in which all issues concerning the economic relations between the two countries were thoroughly addressed, and developments in bilateral relations in recent years were summarized. All elements of previous cooperation were presented in full detail, such as Soviet material, technical, and financial aid to Albania, including the exact amounts allocated and credits used, the status of objects under construction, and the number of Soviet specialists in various sectors of the Albanian economy, along with the specification of their specialization.

The document also offered a political assessment of the state of relations between the two countries. The authors believed that; “the foundations of friendly, fraternal relations between the Albanian and Soviet peoples, between the governments of the two countries have been undermined in Albania.” This state was, according to them, “the main reason for the abnormality that has appeared in relations between Albania and the Soviet Union.”

They considered it “necessary that until the moment the PLA leaders have changed their nationalistic and hostile policies towards the Soviet Union and the CPSU,” certain measures be implemented “in the economic relations between the Soviet Union and Albania.” As part of the financial measures, it was advised that Albania’s ability to receive credit under the Agreement of July 3, 1957, be cut off. It was also proposed that lending not be expanded with new credits for agricultural development and that incentives for previous credits not be given. The use of previous credits to Albania was restricted to the payment of Soviet equipment or goods.

In a similar manner, recommendations “on Soviet-Albanian trade relations” were elaborated. Experts noted the need for a balanced implementation of the bilateral Protocol on Trade, of 1961. It was advised not to sign a long-term trade agreement for the years 1961-1965, with the same goal: pressuring the Albanian leadership to agree to meet again with the Soviet leaders (“if the Albanian side requests such a thing … the answer should be that this issue can be discussed at the highest level”). The final phase of the construction of the Palace of Culture in Tirana was not forgotten either. If the Albanian side inquired about it, they would receive the answer that; “it was an issue for further consideration at the governmental level.”

A separate section of the recommendations concerned Soviet experts in Albania, with a clear timeline for their withdrawal by the end of 1961. It was decided that; “due to the inappropriate behavior of the Albanian side towards many Soviet specialists stationed in Albania, the sending of new specialists should be stopped and the duration of stay of specialists already there should not be extended.” Some exceptions were made for specialists engaged in the design and construction of hydroelectric power plants, as well as geological expeditions. Given the possibility that “abnormal conditions might be created for the remaining specialists in Albania to continue working,” in these cases “it is necessary” to arrange “their return to the Soviet Union, ahead of schedule.”

Some other recommendations provided for the cessation of supply of military-technical equipment, food for people and animals for the Albanian army, by suspending the agreements of September 28, 1949, March 24, 1956, and February 26, 1959. The latter, which concerned the supply of missile technology, was particularly emphasized. It was also decided to ignore the Albanian request for a credit of 125 million rubles for the needs of the Albanian Armed Forces in the years 1961-1965, under the Agreement of July 26, 1960. An analysis of these recommendations shows that the main ones aimed to pressure the Albanian leadership into continuing negotiations at the highest possible level.

The elaborate program to compel Enver Hoxha and his associates to meet again personally was hindered by Albania’s intensified cooperation with the People’s Republic of China. In less than a month, on April 23, a Sino-Albanian trade agreement was signed. As follows from the recommendations approved by the Presidium of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at the end of April, Khrushchev and his entourage expected that the economic-financial pressure on Albania would result in the Albanian leadership’s approval of another bilateral summit to ease tensions. Even today, nearly 65 years later, all the documentary material in the Russian archives related to the preparation of Kosygin’s letter, and the text of the letter itself, are not available to researchers.

We can only speculate that this unjustified sectarianism is solely due to a lack of desire to disclose what was most likely a furious Soviet reaction to the Chinese leadership’s decision to sign a trade agreement with Albania. Therefore, we are still compelled to rely on what Western historiography has stated about this problem since the early 1970s. According to this view, the Soviet First Deputy Prime Minister, Aleksei Kosygin, sent a letter within five days of the signing of the Sino-Albanian trade agreement. His letter effectively signalled the end of Soviet-Albanian trade and credit agreements. Among other things, Kosygin stated that; “it is understandable that the Albanian leadership cannot expect the Soviet Union to help it in the future as it has in the past, with aid that only friends and brothers are entitled to receive.”

The end of April and the beginning of May 1961 marked a new phase in Soviet-Albanian relations. With the activation of Sino-Albanian relations at the end of April, the Soviets realized that it was necessary to clarify the situation with the Vlora Naval Base to the Chinese leadership, justifying the decision to disband it. For this reason, the Soviet ambassador in Beijing was instructed on May 16 to meet with Zhou Enlai, who had raised this issue on his own initiative a few days earlier. Moscow wanted to convince others (in this case the Chinese), that: the Soviet government did not want to withdraw the ships and equipment from Albania, and if this issue has arisen now, it is not at all because of us.

Our steps for withdrawal… are an imposed move since the Albanian side, by pursuing an unfriendly line towards the Soviet Union, has created a completely intolerable situation at the base. Consequently, the base has actually lost its combat capacity, and the presence of Soviet sailors there is accompanied by undesirable incidents, due to the direct provocations of the Albanian military authorities. The Soviet side gave numerous examples of such cases, noting that the Albanian government did not respond in any way to their calls.

No measures have been taken by the Albanian side to regulate the situation, on the contrary, whenever we address the incidents, they try to justify the undisciplined and sometimes provocative actions of the Albanian military authorities, as a result of which the situation at the Vlora base continues to deteriorate. It was noted that “only thanks to the high political maturity, sense of duty, and patience of the Soviet officers, non-commissioned officers, and sailors, it is still possible to avoid conflicts and clashes between our sailors and the Albanians,” and the previous proposal to place all crew and means under the command of the Warsaw Pact commander was recalled.

The refusal of the Albanian leadership to accept this proposal convinced Moscow to withdraw the ships from Vlora. The final part of this phase was the arrival in Tirana on May 19, 1961, of the Soviet delegation, led by Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs Nikolai Firyubin, to negotiate the withdrawal of naval forces from Vlora. Initially, the Albanian side even refused to meet with Firyubin. Furthermore, Tirana wanted to divide the fleet. The Soviets’ final decision was that Firyubin and his delegation could leave Tirana “after the withdrawal from Albania of the eight submarines, the floating base, and the personnel of the Soviet ships.”

The final negotiations began under the heavy shadow of the preparations for a trial against Teme Sejko, Rear Admiral and Commander of the Albanian Navy, as well as several high-ranking officers of the Albanian People’s Army. The trial took place in May 1961 and the accused were found guilty. Some of them, including Sejko himself, were sentenced to death. Officially, all were accused of collaborating with the Greek and Yugoslav secret services and planning a coup d’état.

However, there were unofficial voices, well known even to the highest party bureaucracy, that all those involved in this trial were suspected of a pro-Soviet plot to overthrow the current leadership. The events related to the withdrawal of Soviet submarines, auxiliary ships, and military equipment from the Vlora Naval Base led to the reduction of cooperation in other fields. At the beginning of June, the Soviet leadership decided on a “rapid withdrawal from Albania of Soviet specialists, who were providing technical assistance in various sectors of the Albanian economy.”

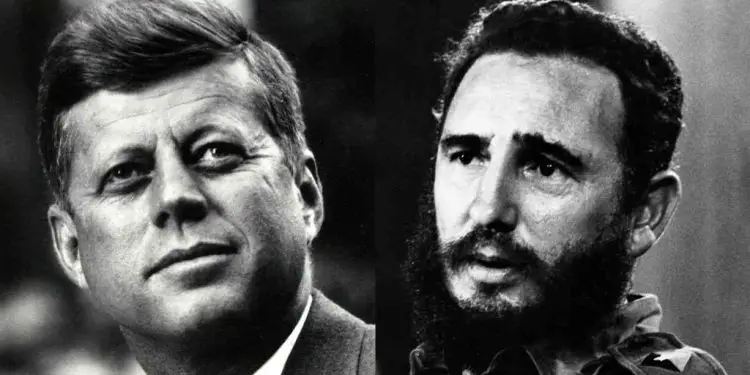

In June, 33 of them were to return to the Soviet Union, followed in July by two other specialists, who were providing technical assistance for the reconstruction and expansion of the production capacity of the sugar and cement plants. An extraordinary testimony to the growing mistrust in relations between Moscow and Tirana was the decision of the Soviet leadership on June 14, concerning the sharing of information about the meeting between Khrushchev and Kennedy in Vienna, held on June 3-4, 1961.

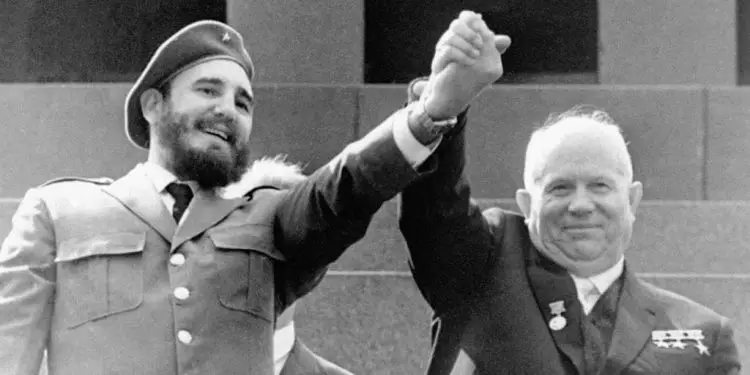

If the leadership of all socialist countries and the leader of Cuba, Fidel Castro, were given the full recordings of the talks, the Soviet ambassador in Tirana was instructed to inform Enver Hoxha only verbally. It was also decided to verbally inform “in confidence” the heads of states or governments of Afghanistan, Burma, Brazil, Cambodia, Finland, Ghana, Guinea, India, Iraq, Morocco, Mali, Mexico, Nepal, the United Arab Emirates, Somalia, Ceylon, Ethiopia, as well as Yugoslavia. This was a clear decision that in the eyes of the Soviets, the Albanian leadership stood at the same level as the Yugoslav leadership, which until recently was described as revisionist and almost hostile.

The state of relations with Albania and the need to send a response to its Ministry of Foreign Affairs was again on the agenda at the meetings of the Soviet leadership on June 13. Khrushchev and his associates were informed “about the facts of the unworthy behaviour of Albanian cadets studying in Soviet military schools.” A note for this purpose should be sent to the Albanian government. On June 17, Khrushchev and Mikoyan were the two main speakers in the discussion of Albanian issues, a significant item on the agenda that day. Memorie.al