A Humanitarian Event That Must Be Remembered

World War II, Albania, 1944

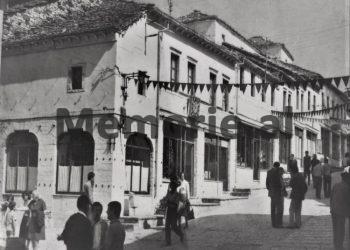

Memorie.al / In 1944, Ludovik Deda, a 22-year-old youth from the prominent Shkodran family of the Dedjakups, was serving with the German military forces as a non-commissioned officer in an Albanian military unit, primarily tasked with maintaining order and peace in and around the city of Shkodër.

One freezing winter morning in mid-January 1944, a courier from the Wehrmacht headquarters stationed in Shkodër delivered an envelope to Ludovik Deda. It contained a summons for a meeting with the German Commander in his office at 3:00 PM that same afternoon.

At the appointed time, Ludovik arrived at the Commander’s office. He was received politely and ordered, briefly and in few words, to be near Bar “Kursal” in Tirana the following day at 12:00 PM, where the Commander himself would be present for a matter he would understand upon meeting. Before Ludovik left the office, the Commander cautioned him: “Careful, no one must know about today’s conversation!”

The next day, precisely at noon, Ludovik entered Bar “Kursal” in Tirana and spotted the German Commander at a corner table. The Commander greeted him and invited him to sit, subsequently asking the waiter to bring Ludovik coffee and water. Ludovik felt deeply moved and anxious by this mysterious meeting.

While Ludovik drank his coffee, a man approached the table, greeted them in German with a distinct accent, and sat down quietly. The Commander introduced him, and Ludovik realized that the third person at the table was the “former chief of Italian secret services in Albania.” It appeared that while the Germans had captured and deported almost the entire Italian military in Albania to “death camps” as traitors following the capitulation of Fascist Italy on September 10, 1943, they had retained this gentleman as a special advisor due to his extensive knowledge and experience of the Albanian environment.

After some conversation, the German Commander presented Ludovik’s mission: “Since the German army needs timber to be transported from Shkodër by water via the Buna River, there is a need to purchase a sea-river vessel for the German army, which must sail from Durrës and anchor at the river port of Shkodër.” Ludovik was instructed to meet an experienced person in Durrës regarding the vessel. He was handed the necessary funds along with a strict order: for any potential problem, he was to contact only the German Commander himself.

A few days later, Ludovik met the recommended contact in Durrës and, following his advice, purchased a wooden sea-river vessel with a capacity of about 150 tons named “Papagalli” (The Parrot). He paid an advance to two sailing specialists (a captain and a mechanic) for their services and sailed with them toward Shkodër. The voyage was successful; they anchored the ship in the bay created by the Cement Factory rock in Shkodër on the Buna River, where two German soldiers were waiting to take the vessel under guard.

During the next meeting in Shkodër, where Ludovik went to report the completion of his task, he learned the truth of the “Top Secret” mission: The German Commander, along with several loyal collaborators (Wehrmacht officers in Shkodër), had undertaken to save dozens of Jewish families from the clutches of the notorious Nazi “S.S.” units. These families, previously residing in Serbia, Kosovo, and Macedonia, had been “lucky” enough to escape the vigilant eye of the S.S. and were currently hidden in the homes of Shkodran citizens.

The German military command in Shkodër had “received a request from their colleagues in Vlorë for a timber supply for army needs,” which was to be transported by the ship “Papagalli.” The timber would be arranged on the deck, while the members of the Jewish families would be hidden beneath the wood in the belly of the ship, bound for another destination. Ludovik was tasked with staying near the ship 24 hours a day and escorting the group of Jews to their final destination.

The operation was fraught with uncertainty, but so far, everything had gone according to plan. The greatest difficulty was the clandestine arrangement of the Jewish families into the ship’s hull, as the route from the city of Shkodër to the anchorage point necessitated crossing the Buna Bridge, where the Nazi S.S. had a checkpoint.

First, the ship was loaded with timber on the deck; a concealed passage was left open to enter the hull beneath the pile of wood. Since the process of boarding the Jewish families was expected to be long – as it had been decided that they would cross the S.S. checkpoint at the bridge dressed as local peasants, accompanied by Albanians, no more than two at a time – a problem arose: someone might become suspicious as to why a ship intended for the German army, already loaded with wood and ready for sail, was remaining stationary for so long. For this reason, two “selected” mechanics of the German army began “repairing” the engine and mechanism of the “Papagalli,” which, “surprisingly, turned out to have many defects?”

The programmed process of passing the checkpoint and secretly settling the Jews into the ship’s hull took nearly 27 days. In total, 45 members of Jewish families were clandestinely sheltered on the ship. Meanwhile, as more people occupied the hull, fulfilling their vital needs under clandestine conditions became increasingly difficult. Finally, the day of departure arrived: February 25, 1944. That day, two German officers joined the “passengers.” The Buna River was high with water. The voyage began well, the ship moving quickly aided by the river current. Several German military outposts that controlled river traffic with iron nets were passed without detailed inspection, as the German officers on deck communicated with their colleagues at the checkpoints, presenting the command’s order for the timber delivery to Vlorë.

The optimism that surged through the passengers as the ship exited the mouth of the Buna River and began sailing the Adriatic Sea toward the free world – with a destination of Bari, Italy (an area already liberated by Allied forces) – did not last long. Suddenly, the ship’s engine stalled. The “Papagalli” was at the mercy of the waves, which fortunately were quite calm that day. Anxiety reached its peak; the mechanics worked frantically to find the fault, while the German officers used their “transmitter-receiver” radio and secret codes to communicate with “those” interested in the Jewish rescue operation. Suddenly, about 100 meters from the ship, a British submarine “sprouted” from the sea surface. It towed the “Papagalli” to its destination in Bari, where all the ship’s passengers initially found shelter in a war refugee camp near the city.

It is worth noting that this event – as unique as it is humanitarian – honors the morality of not only the Albanians but also the Germans, demonstrating that not all German military personnel were against the Jews. Yet, it is remembered by no one. Why? Is the event unknown? No, it is known, but they do not want to know it… because they do not want to remember it.

At the beginning of the third millennium, I happened to participate in a meeting of the Albanian-Israeli Friendship Association held at the “Luigj Gurakuqi” University in Shkodër. Several Shkodran families who had sheltered Jewish families during the Nazi terror were being honored. I remember asking for the floor and briefly recounting the story written here. I was left somewhat surprised because the leaders of the activity showed no interest in what I told. Later, when I analyzed the psycho-political environment of the organizers through the lens of my life experience under the communist dictatorship, everything became clear to me. No comment!

Everything speaks for itself. The dogmatic, puritanical ideological processing of a segment of society does not allow them to understand reality, the truth that surrounds us: “Good and evil coexist in an inseparable binomial, like a symbiosis; there is no good without evil and no evil without good.” Whether we like it or not, this is the reality. “Reddite quae sunt Caesaris Caesari et quae sunt Dei Deo” – Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.

It remains to our honor to present public respect and gratitude for the humanitarian work of saving Jewish families from the clutches of the Nazi S.S. at the risk of their own lives in the spring of 1944 – for the Commander and his loyal Wehrmacht officers in Shkodër, for the residents of Shkodër, and particularly for my friend who is no longer with us, the late Ludovik Deda.

Note:

This account respects the narrative of the main character, Mr. Ludovik Deda, as conducted at his home in Pescara, October 1997. To those to whom the above event may seem unbelievable, I invite them to verify the archives of the WWII refugee camp near the city of Bari, where the truth is preserved. / Memorie.al