By Taisa Batkina Pine

Part six

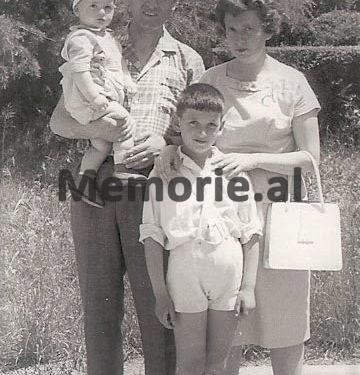

Memorie.al/ publishes the unknown story of the Russian Taisa Batkina (Pine), originally from Tula, Russia, the third child of a very poor rural family, who was left an orphan at a very young age, after her father lost her life while working in one of the coal galleries on the outskirts of Tula, where he worked as a miner (shortly after escaping arrest, accused of “supporting the enemies of the people”) and she grew up with difficulty great economic, as their city continued to be under the bombardment of German forces, which had reached as far as near Kursk. Taisa graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry, near the ‘Lomonosov’ University of Moscow, where she met and married the Albanian student, Gaqo Pisha, originally from the city of Korça, who at that time was studying at the Faculty of Philosophy in Moscow and both together in 1957, they returned to Albania, together with their newborn son, Sasha, where they started living in the city of Tirana, Taisa was appointed as a professor of Chemistry at the State University of Tirana, while Gaqo, in the chair of Marxism- Leninism, where they worked until 1976, when the State Security arrested Taisa Batkin on fabricated charges, accusing her of being a “Soviet KGB agent” and sentencing her to ten years in political prison, which she suffered in the “Women’s Prison” in the city “Stalin”, from where she was released in 1986, while her husband, Gaqo Pisha, had died in 1983, from a serious illness. The tragic story of Taisa Batkina (Pine), in the inhuman camps and prisons of Enver Hoxha’s communist regime, where she spent a decade of her life, along with many compatriots from the former Soviet Union, or other Eastern European countries, comes through her memories, published in a book entitled “We hoped and survived”, memories which, her son, Aleksandër Pisha, kindly offered her for publication, in Memorie.al

We hoped and survived

I dedicate it to the bright memory of my husband, GAQO PISHA

This is a memoir. In it I want to tell about my life and that of my friends, Soviet women, who tried prison for several years just because they got the courage and got married and linked their fate with that of Albanian students. The prison was part of the great GULAG in the small Balkan country, Albania, where for many years the bloody communist regime of Enver Hoxha ruled, who was a loyal student of Stalin and a follower of his cause.

Through this book I would like everyone to learn about the inhuman trials we experienced and the horrible years we spent in Albanian prisons, just because we… fell in love! And let no one ever forget what totalitarianism, despotism is and what the consequences of this system are.

Continued from the previous issue

Unbearable calm and sometimes screams, to make the soul ice, noise of steps and calm again. The guards did their work quietly, walking; approaching the door to see through the hole what was going on in the cells, so easily that from the inside you could not understand that anyone could see from the hole covered with netting. Suddenly, in the midst of this calm, frightening grunts were heard, clothes that made you tremble, jump upwards, as my heart started beating more often. The door slammed open and a rude voice said, “Hey, you get up!” Walking down the hall, in the semi-darkness, the walls and doors are painted brown, many doors, all side by side, and all hanging massive locks. Everything was well thought out; every little thing was invented to break you, to oppress you, to frighten you. One can get used to anything, but I never got used to the noise of locks and locks, the creaking of the door when it was opened and closed, and the crackling of the hole in the cell doors. During the detention, there were no meetings; it was complete darkness and misinformation, no books, no newspapers, no paper, no pencil. In order not to go crazy, to deal with something, I invented everything: I took a straw came out of the dirty mattress and “wrote” with it on the floor, I combined whatever words, some kind of crossword puzzle.

When the door opened, one quick move was enough to turn everything into a straw hand. One day I was rushed to the investigator and I could not hide my crossword puzzle. When I was returned to the cell, Supervisor Vasilika, (she was noted for her special vigilance and ferocity), read the words on the floor, remembered that I had a hidden pen, and went straight into the cell, but the straw was scattered. I escaped without shouting and without swearing. The door closed and I was left alone again. Poems helped me to deal with something, to postpone the endless hours, more than anything else. I was trying to recall verses I once knew by heart and loved very much. Most often I remembered Pushkin, Lermontov, Esenin and Simonov. I recited them, first in a low voice, then out loud. The door window opened and the guard shouted angrily: “Enough!” I started repeating the poems in a low voice. I remembered many of them and repeated them to myself, over and over again. This helped me to move to another world, very distant, and sometimes it occurred to me that I would never return to it. When we met later in the camp, I learned that Pushkin’s poems had saved other of my friends, had helped them survive, not play games. The first few days, when my neighbor knocked on the wall, I too wanted to learn this way of communicating. The neighbor told me he was knocking alphabetically. One knocked – A, two – B etc. But I, although I knew the alphabet of the Albanian language, could not “read” the knocks, because I repeated the alphabet very slowly. Then I decided to memorize the number of each letter and count the knocks. And so I did. It did not go wrong!

After I was released from prison, I read Fatos Lubonja’s book: “Review” and learned that men used to communicate in a more efficient way, but we women did not know that ‘ABC’ so we knocked on every letter. Sometimes we muttered something, sometimes we learned something from the women of the neighboring cells my we spent time! Knocking was not easy, even dangerous; the guards and guards constantly searched, approached the Tina, eavesdropped and caught the violators. One day the guards did it in my cell and just because I convinced them with the unsullied look and told them that I did not know the alphabet of the Albanian language, I escaped from the dungeon. We usually knocked in the evenings, when the bosses would run home, and the guards would finish their work and gather at the end of the corridor to mumble among themselves. I remember two special cases during the “interconnection”. Next to my cell, on the right, stood someone receiving food other than ours. Instead of the black skin they gave us the rest, they brought puree, if any. I knocked and asked for the name. “Mina,” she replied. Later, when we were in the camp, I learned that there were two sisters, Mina and Nadira, two young peasant girls, accused according to a fabricated case… of cow work. I will write about this in detail below. During the investigation, Mina became seriously ill. The process was political. Mina’s life had to be saved until the trial took place. Even my neighbors on the left had noticed Mina’s food and started asking me who was staying in that cell. I started knocking: “M-I-N-…” At that moment I heard the signal; the neighbor scratched the wall, which meant, “I got it, and you might not go on.” Six months later I met my neighbor in the camp and learned that she had taken the letters “min si” as the first words “minister”. It was the time when almost all the party and state elite were put in prisons, so the presence among the prisoners of a ministry did not surprise anyone.

The other case

It would have been October 1, 1976. I was taken to the investigator, who was reading the newspaper. I stared at the newspaper as if burned for water. For 5 months I did not know what was going on in the world. I read: “Greetings to the leadership of the ALP for the leadership of the Communist Party of China.” Mao Zedong’s name was not. What happened to you? I did not ask the investigator because I might receive a harsh or mocking response. When I returned to the cell, I thought of asking the neighbors; they were “fresh”, they had just arrived a short time ago. I was afraid to ask open text. In Albania I had learned in time to be silent, not to ask. I finally made it up: I knocked on the question: “Will Mao Zedong comes to Tirana”? I got the answer: “He is dead.” “Oh God! – I thought. “Maybe with his death, something will change and we will be released”? Vain hopes, unfounded anywhere! Now fear, hopelessness, loneliness took its toll. Suddenly I started having hallucinations. It was as if I heard Sasha’s voice calling to me: “Mama, mama”! I thought in horror that he had been arrested, he called me… and I was almost out of breath. This went on for a few minutes and passed me by, then started again, more and more often. I was about to faint; I lay long, motionless, or trembled, screaming. In such cases in my cell brought the neighbor, so that for some time I was not left alone. Then the neighbor was taken out and everything started from scratch.

Investigation and trial

All the interrogations melted into a long and daunting process. I cannot write them all in order, day after day; for this you must have kept a diary. In the cell this was quite impossible; it was forbidden to keep paper, pens, newspapers, books. In the camp it did not even occur to him to keep notes; there just had to survive. I first met my investigator when I was called to sign the arrest warrant. I do not remember anything; everything was like in a fog. I was then questioned for the first time and then the further prolonged, heavy completion of the survey continued. Who are the parents? Where did you study? When did you finish? Where did you work? Have you been convicted? Etc. I was just amazed; they had followed me foot by foot, they knew everything about me, down to the smallest detail. The first question they asked me: “Now tell me about your friends and acquaintances.” I calmly received this question. I mentioned 2-3 names. My friends were worthy people. Among them were doctors, pedagogues, engineers. All worked great; they respected them, they had good families, children. I was convinced that by mentioning the names, I was not doing anything wrong. What a fool! It did not even occur to me that every word of mine was used against us. Investigators were not satisfied with my answer. They even mentioned the names of some of my acquaintances, even those who had fled to the Soviet Union in time. In their questions I discerned malice, rage; as if they were angry that those people had fled, they had escaped from their hands. On one of the first days of imprisonment, the door to my cell slammed open. I lifted on foot. Entered the cell accompanied by the guard, a hairy man. He looked me in the eye. His face took on a wicked look. “Ah, here we are! Hey, how are you? Do you have a complaint? – He asked me, without introducing himself. One by one the questions crossed my mind: “Complaint? For what? Who should I complain to? “They do not know that I did not commit any sin, that everything that is happening is planned in time.” But silent. that man came out

A few days later I was taken in for questioning. That man with black hair was there. Introduced: “Prosecutor!” and continued: “Aha! Your beautiful life is over! Who will wear your rare clothes? Your husband will not roam abroad anymore! ” “My husband abroad?! What beautiful clothes? ” And I perceived so much evil in his words, that it was as if foam came out of his mouth. Like me and all my friends, they were his personal enemies. (Kostallari, on the other hand, was a linguist, academic, went abroad to scientific conferences and symposia. Perhaps this aroused envy and malice in others). “You are wrong,” I told him. “I am Taisa Pisha, the wife of Gaqo Pisha.” He was confused, but soon recovered. “A-a, your husband is the one whose hands are shaking. You see how gravely guilty you are. “If you were not guilty, we would not have arrested you and separated you from your sick husband.” I did not speak. I thought to myself that these people never feel sorry for anyone, ever! He asked me the same questions as the investigator. “Count all your friends!” “I told the investigator,” I replied. “Repeat”! I repeated the 2-3 names I mentioned to the investigator. But this did not satisfy the prosecutor. He started counting the names of Soviet women for me. “Do you know that?” What about this? ” Yes, I knew almost everything. We had a good relationship. In the voice of the prosecutor, when he mentioned the names of my friends, there was so much hatred, so much anger, that fear entered my heart. The prosecutor raised his voice, started shouting: “Why does he not cooperate with the investigation? You will not tell”?! “We have never had hostile conversations, I have nothing to say.” “It’s not true! – Shouted the prosecutor, – we will get rid of you… you are enemies… you are spies! … You have helped the Soviet Union, which does its best to overthrow the popular power in Albania. You are anti-Stalinist, you supported Khrushchev, but our bodies unmasked you”! etc.

All this to confuse, to create the conviction that the car that had stuck to us, would not let go without grinding us well; that they would do whatever they wanted with us. The investigation was conducted regularly by two investigators. With an investigator was not allowed. Authorities did not trust the man and investigators guarded and eavesdropped on each other. Then, they thought that women could accuse the investigator of sexual harassment. There have been such cases. But when one of the two investigators wanted to hit you, the other left the room. Everything without witnesses. My investigator was Fejzo Aloçi. Not very smart man, with secondary education. Fatos Trebeshina worked with him as a couple. Yes, he was good, with “grams”. They each played their part: the good Fejzo and the bad Fatos. Although Fatos even without this role, he was wicked, angry, treacherous and vindictive. Sometimes Fatos also played the role of the “best” and before leaving the questions, he told me that everyone at home is fine. I could not trust them, but we were happy to believe that they were telling the truth and we calmed down a bit. Such investigators had to be: people without morals, rude, noisy. They need to believe in the order that has brought them out and that pays them well. This work provided them with all kinds of material goods, but also respect mixed with fear of the people around. To preserve these goods, they were ready for anything. This is how interrogations went, sometimes sweet smiles, sometimes screams. “Hey, how do you feel?” Do you like soup here? ” (“Soup” was a black face, terrible, that you can eat only after a few days of hunger). “What! – I answered. “During the war we tried even worse.” Then the soup was not mentioned to me anymore. From the first interrogation until the end of the investigation, I was repeated the same thing: “Accept, accept! Pure heartfelt affirmation gives us the opportunity to have our help. “If you do not accept, you will have it worse.”

I did not know what to accept, so I repeated that I was not guilty. And I felt tiny, insect, cockroach… no, not cockroach, but a nothing detached from life, trampled underfoot, crushed, turned into a car, which in no way releases its victim, into any way! “Our judicial system is never wrong!” – repeated the investigators. In one of the interrogations, I first asked to read the Criminal Code. I was completely helpless in that state, where I was stuck, I had no idea of the Criminal Code, I was never interested in such things, because I had never done anything illegal. The investigators laughed: “Look, what do we want!” I did not see the Criminal Code either during the investigation or before the trial. I knew that in Albania, since 1966, there was no lawyer for the defendant. Lawyers for post-war Albania participated in the political process. They often came out against lawlessness, against arbitrariness. But most of them were persecuted, and in 1966 the bar was liquidated. However, I decided and asked for a lawyer: “Our courts are the most rights in the world, we do not need lawyers! “Then you are educated enough to know how to defend yourself,” the investigator replied. There I said something about Roman law (though, to be honest, I had no idea what it was). I said that in court should be the defendant, defense counsel and judge. But they waited for me, because Roman law belongs to the past, everyone has forgotten it.

And again: “Show! Show! Prano! Acceptance with a pure heart will make it easier for you. We are giving you the opportunity to repent and receive a minimal punishment! ” And again: “What were you talking about with your friends? What were you reading? You are all anti-Stalinist ”! “Anti-Stalinist? Stalin died twenty-some years ago. What can I have to do with it? The investigator began to shout: “Our party is the only Marxist-Leninist party in the world, all the others are revisionists. We are loyal Stalinists. Whoever is against Stalin is our enemy! And again: “What were you reading? What were you talking about … ”? I counted some books I had read shortly before I was arrested. Among them “Memories” of I. Ehrenburg. Vol. 1. He took note. When I was called again, he shouted: “In that book Ehrenburg writes against Stalin”! And again they asked me to admit my guilt, they told me that in vain I insisted on mine, that there was so much material against me that they could shoot me. They showed me my name on the cover. “Oh God! – I thought. “How many reports have there been for me”! Then, during the investigation, I realized that in addition to the reports, in those volumes were also the translations of the letters I had sent or received, were the traces of all the movements I had made through Albania! “How much work, how much money was blown up! Will I be able to dispel all these slanders? One day, during interrogation with shouts and threats, the door suddenly opened and a tall, unwashed, unshaven, worn-out old man entered the room. He could barely stand. “Do you know this man?” – they asked me. “No,” I replied. “What about you?” – addressed the old man. – “Yes. It is Taisa Pisha, the wife of Gaqo Pisha “. Only when he started talking did I recognize him. It was Mandi Koçi, the husband of Roza Koçi.

Mandi, was from the same place as Gaqo, so we knew each other. During the war he had a shop in Korça, where illegals hid. Mandi himself, a communist, anti-fascist, had taken an active part in the National Liberation War. After the war he was sent to study in Moscow, where he completed a course and became a cinema operator. In Moscow he met a girl, Roza, whom he married. Roza graduated from the Faculty of Philosophy of Moscow University, had learned Albanian and spoke it fluently. After Roza left for the Soviet Union, Mandi was expelled from the party and fired. After much effort, he managed to start working as a photographer. Like all Soviet women men, he had no family ties at all to Russia. In 1974, we heard that he had been arrested. Suddenly I realized why they kept asking me what I was talking about with Rosa. And, although I had not seen Roza since 1960, but I did not have close friends, the investigators were looking, screaming…! The investigator addressed Mandi: “Tell me, what were you accused of and how many years were you sentenced”? “25 years for espionage,” replied the unfortunate. How I held myself and did not shout, I do not know. This poor, sick old man, who undoubtedly had no guilt… 25 years! “Now tell us what Taisa was talking about with Roza.” Mandi could not utter a word, something stammered, confused. The investigator began to read his depositions. Mandi shook his head in approval. He had testified as if in 1959 (17 years ago), I had told Roza that: The Soviet Union would attack Albania. This was horny stupidity and I could not hold back the laughter, at first in a low voice, then, little by little the laughter turned into hysteria. I laughed and cried and barely collected myself. “What is this nonsense? I almost did not communicate with Roza, not then to say such things to her, when our countries had such good relations. On the other hand, Mandi did not know Russian, even a little he had known and had forgotten in time. “They spoke Albanian at home, he never understood anything we said to each other,” I told investigators. They both started shouting that Mandi’s words were true. I did not sign the protocol, but that did not prevent this report from being made in court./Memorie.al